Looking at the late Empire’s administrative practices, George Padmore provides us with some valuable background to the situation in France’s former West African colonies today.

‘Subjects and Citizens in French Africa’ by George Padmore from The Crisis. Vol. 47 No. 2. February, 1940.

It makes all the difference in the world whether an African is a citizen of France or a subject. The French embrace the very small number of leading black citizens, granting them full social equality, but only for the purpose of controlling the dark millions who are only subjects.

“LIBERTY, Equality, Fraternity.” It is behind this once progressive slogan of the French Revolution that the present-day rulers of the Third Republic have so skillfully masked their actual reactionary and repressive colonial policy. So cleverly has the mask been used that the French capitalist class has been able, more than any other imperialist power, to deceive the world regarding the true nature of its despotism towards its colonial populations.

Most non-French Negroes, especially Americans, visiting Paris, with its relative absence of color prejudice, its gaiety and charming cultured atmosphere, invariably adduce that France is the most liberal imperialist nation in the world. There is no greater illusion. It is quite true that the French, as compared with the Anglo-Saxon peoples, manifest less racial antipathy toward people of color. But the same can be said of the Spaniards—even the supporters of France— the Italians, and other Latin races, regardless of their political ideology. No one, I am sure, would have the temerity to accuse me of being an admirer or defender of Fascism. Nevertheless, from the standpoint of interracial congeniality, I would rather live in Rome than in London. But were I to judge Italian colonial policy from this angle, I could truly be accused of superficiality. Thus, while I personally consider the French in many ways a charming people and Paris a delightful city, this in no way blinds me to the fact that French colonial policy is as reactionary, and in many respects more repressive than that of the British.

Those people who have not made a comparative study of colonial administrations, but who form their conclusions on the basis of acquaintance with “assimilated” French Negroes, find it almost impossible to appreciate how very minute is the section of the French colonial populations permitted to enjoy the status of citizenship, or even permitted the enjoyment of elementary civil liberties. I hope that this article will help to correct this fallacy, for once corrected the spectacle of French Imperialism will be revealed in its true perspective, and the relation of the colored races under the Tricolor seen in its right colors.

Largest African Empire

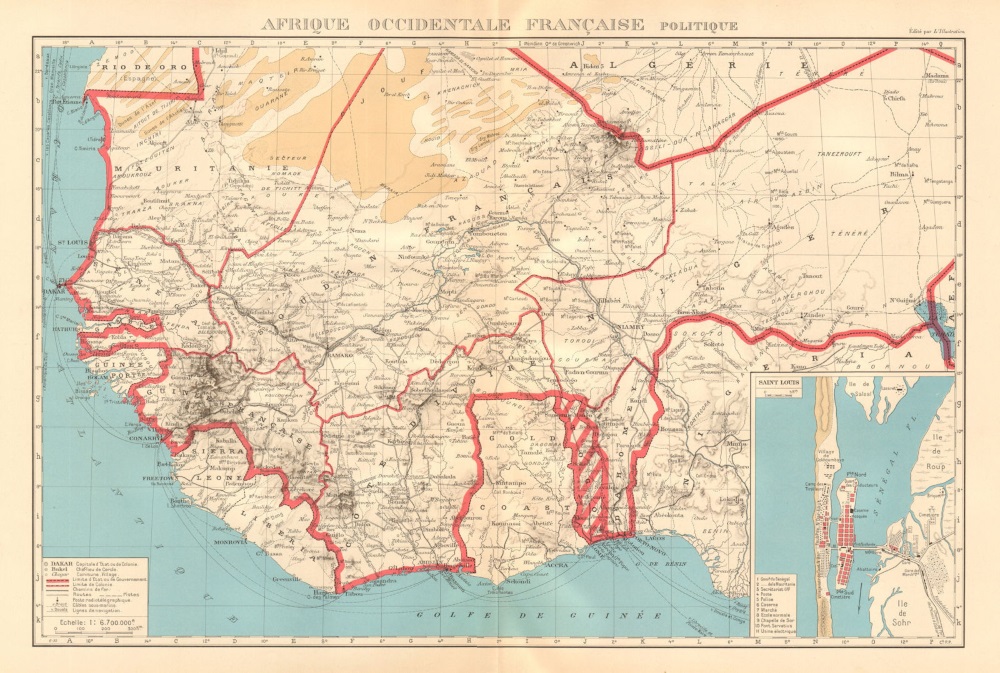

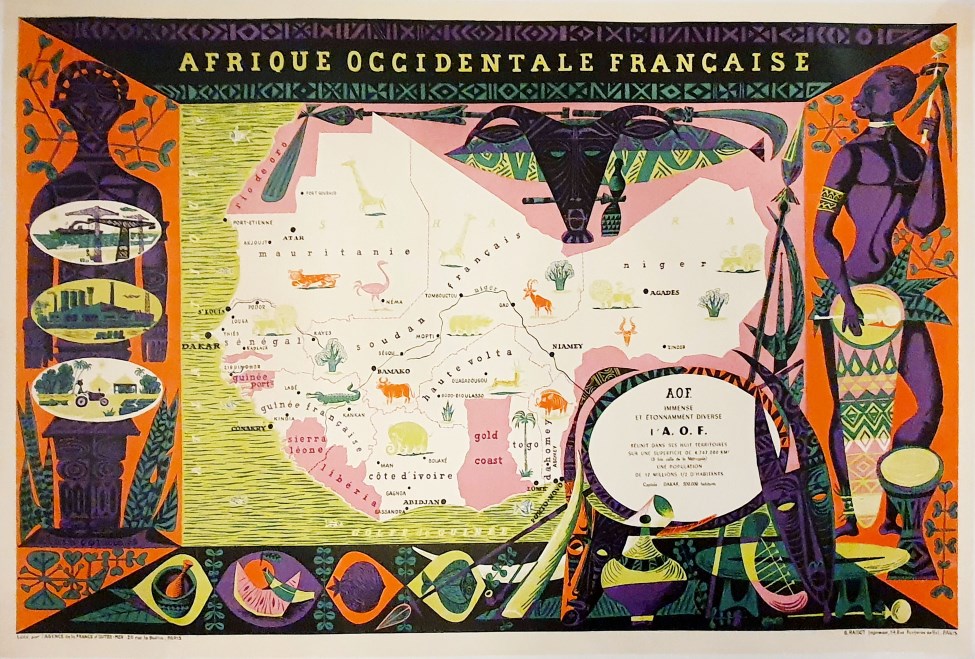

France has the largest Colonial Empire in Africa, the creation of a deliberate national policy. Upon the loss of Alsace-Lorraine in 1871, the Third Republic turned to Africa to acquire there lands which would compensate for these provinces. St. Louis, Dakar and Goree on the Senegal coast and Algeria in the North were then the only French possessions on the continent. Today the French Empire stretches from the Mediterranean in the North to the Congo in Central Africa; from Senegal on the West coast to the frontier of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, with French Somaliland on the Red Sea and Madagascar off the East coast of Africa. This Empire covers a total area of four million square miles, with a native population of over sixty millions.

The most valuable possessions, economically and militarily, are Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco, in North Africa. Situated in the temperate zone, they have afforded favorable facilities for white colonization. There are 987,252 Europeans living in Algeria, most of whom are French, and of 196,000 in Tunis, 95,000 are Italians. Though the largest of the three colonies, Morocco has the smallest white population—about 195,000. The total native population of these territories is about 14,000,000 distributed as follows: 6,247,432 in Algeria; 2,603,000 in Tunis; and 6,101,440 in Morocco.

Methods of administration differ as much in the French colonies as in the British. Here, however, I shall not discuss the problems of the Berber-Arab peoples of North Africa, but will confine myself to the Negroid races who inhabit the west and equatorial sections of French Africa.

Two federated groups make up French tropical Africa: West Africa (Afrique Occidentale Francaise) and Equatorial Africa (Afrique Equatoriale Francaise). The federation of West Africa, established in 1895, was reorganized in 1933. Colonies included in the new scheme are Senegal, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Dahomey, Mauritius, Niger and Dakar dependencies. The Upper Volta lost its colonial independence, and its territory and population were incorporated into Niger, Suden and Ivory Coast. The total area of this federation is 1,604,157 square miles, and the native population nearly 15,000,000. There are 24,719 whites, of which 17,631 are French citizens—officials, traders, merchants, and planters — scattered throughout the various regions.

The French Sahara, a desert region of 1,500,000 square miles, forms the northern boundary of Upper Senegal, Niger and Chad. The other federated territory, French Equatorial Africa— sometimes referred to as the French Congo—is composed of four colonies: Middle Congo, Ubangi-Shari, Gabem and Chad. Although they cover an area five times larger than France, the total population is only 34 millions, a density of four or five to the square kilometre. The story of the depopulation of these equatorial lands is one of the blackest episodes in the colonizing history of French Imperialism in Africa. The story in all its harrowing details has been written up by DeBrazza, Felicien Challaye, Albert Londres and Andre Gide.

All the territories of Equatorial Africa are administered collectively by a Governor-General and a Secretary-General. The West African colonies, however, each have a Governor, all of whom are responsible to the Governor-General of the Federation. Both Governors-General are responsible for the actual administration and execution of civil and military policies in their respective federated groups, subject to the control of the Colonial Minister. But fiscal policy is directed from Paris, it being necessary for all budgets to have the approval of the home government before adoption by the Conseils d’Administration. The French Parliament is also responsible for authorization of all loans. There is, in fact, a centralization of authority, making for the economic unity of the Empire.

Chiefs Have No Authority

Conseils d’Administration are advisory bodies which assist the Governors-General in the formulation of local policies. Forty-five members compose the Colonial Council for West Africa, most of them European officials and handpicked chiefs from Senegal. There are a few elected members, like the Deputy for Senegal and representatives of the Municipal Councils of Dakar, St. Louis and Goree. Recently an attempt has been made to consult indigenous opinion outside Senegal, for which purpose a number of consultative bodies known as Conseils des Notables indigenes have been created in various parts of West Africa. These native dignitaries, however, are not necessarily hereditary chiefs but government functionaries.

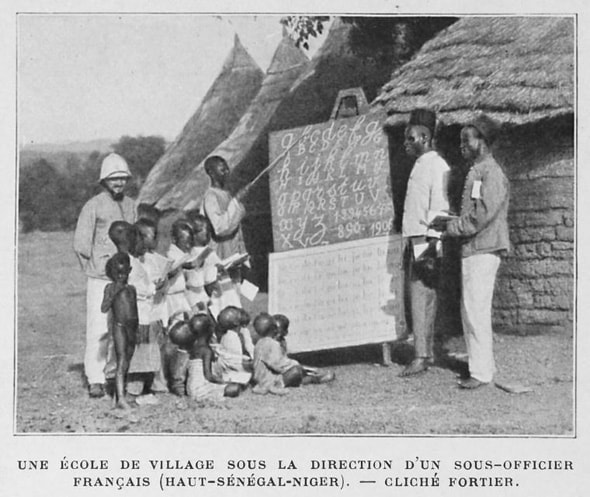

According to the Minister for Colonies, the aim of such councils is the gradual “formation of an elite which will later be able to cooperate more closely and in a more personal manner in the economic and financial life of the colony.” Such so-called chiefs are useful to the French officials as interpreters of Government decrees to the unassimilated masses, as tax collectors and labor recruiting agents.

The individual colonies are broken into cercles. Each of these administrative units is directed by a white Commandant, whose black agent is known as a chief. These agents are the products of special schools for the sons of chiefs and official interpreters, maintained for the purpose of producing a native elite which has assimilated French culture. They have no authority of their own, but speak and act for the Commandant of the cercle. They are paid for their services by a rebate on the taxes they collect, an incentive to squeeze as much as possible out of the native peasants.

Divide and Rule

The natives of the French tropical colonies are grouped as citizens and subjects. All natives born in the towns of St. Louis, Dakar, and the island of Goree are citizens, the black populations of these places having been elevated to this status by a purely historical accident, which had relation to events which occurred in the island of San Domingo (Haiti) during the French Revolution. As a result of the revolt of the Haitian slaves, many of whose ancestors came from Sene-Gambia, the Paris Assembly, in its Declaration of the Brotherhood of Man in 1794, abolished slavery throughout the colonies then in the possession of France. These covered St. Louis, Dakar and Goree at that time the only French possessions on the West coast of Africa. With the hardening of reaction against the Revolution in France, slavery was reestablished in 1803. Negroes found themselves once more the chattels of their white masters. But since freedom once gained is not readily ceded, the West Indian blacks took up the revolutionary struggle which had languished in France. Under Toussaint L’Ouverture they led an open rebellion against their white overlords, and after Haiti had won its freedom from French sovereignty, the French bourgeoisie in its own defense granted full political rights to all free persons existing in their colonies in 1848.

Since that time all Africans in the three territories mentioned above, along with those in the other French overseas possessions of Martinique and Guadeloupe in the West Indies, French Guiana in South America, and Reunion in the Indian Ocean, all of which formed part of the French Empire at the time of the 1848 decree have had the vote but natives in French Africa born outside of St. Louis, Dakar and Goree are subjects, as these territories were acquired after 1848, when the French bourgeoisie, having consolidated their power, had grown conservative and saw no reason to extend the rights of citizenship to native races collectively. Thus while a million and a half natives living in the coastal areas of Senegal are citizens, the 60 millions living outside these territories are subjects. Let us see the significance of this distinction.

The black citizens of Senegal elect their own Deputy to the Chamber of Deputies in Paris, and share with the white settlers a certain amount of autonomy in the administration of Dakar, St. Louis, and Goree, which have the status of municipalities. A privilege of great significance allowed to the Moslem citizens of Senegal is the right to many wives, a privilege denied to white Frenchmen under the Constitution.

The subjects have no constitutional rights, but by fulfilling certain civil and military qualifications they may apply to the government to grant them citizenship. For example, Monsieur Mandel, the French Minister for Colonies, has issued a decree since the war, the significance of which may have escaped many. It states that the right to vote will be given to natives of Madagascar and others who voluntarily enlist for military service ; a privilege that will not be extended to those who are conscripted! In this way, the French hope to stimulate recruiting in the colonies. Such natives after the war will be included among the elite, and will be exempted along with other black citizens from such obligations as prestation or forced labor, payment of head tax, and other irksome duties which are the penalty of being a subject. Military service for citizens is limited to two years, which are spent in West Africa. Subjects, on the other hand, are compelled to give three years, which are spent mainly away from home, for the most part in North Africa, Syria, Indo-China, or in France. These are the black mercenaries of French Imperialism, and are used as shock troops in hazardous military undertakings such as suppressing revolts in Syria, Indo-China, etc., and as strike breakers against the white proletariat of France.

The Black Elite

The elite, as full-fledged citizens, have the right to be tried under French law and to retain the service of counsel. Subjects are dealt with by political officials and chiefs, according to local statutes and decrees. A distinction in cultural policy is also made by the Government between the two classes of blacks. The children of the elite are provided with the same educational facilities as those of Europeans living in the colonies, and theoretically are eligible for civil and military posts on the same terms as white Frenchmen. In actual fact very few do enjoy these advantages. Occasionally, as a gesture to prove the liberality of the mother country, an African-born native is given a position of some minor importance. Those Negroes who are elevated to responsible executive positions in the French Colonial military and civil services are invariably West Indian Negroes from Martinique, Guadeloupe and Guiana, who, by reason of their long contact with French culture have become “assimilated.” And it is this type of Negro whom one so frequently meets on the Paris boulevards, and who is responsible for the current fallacious view of the liberality of French Imperialism.

Subjects are excluded from even the most minor Government positions and are denied the opportunity of holding commissions in the army. This division between citizens and subjects is a deliberate and calculated policy of French Imperialism, aimed at aligning the elite with the white ruling class, of which they consider themselves a part. Since the French are more or less free from race prejudice, their relationship with “assimilated” Negroes is far more candid than that between the English and the educated native intellectuals of the British colonies. The French officials make a conscious effort to draw the elite to themselves, in order to deprive the inarticulate masses of educated leaders. This device, which enables the French imperialist class to cloak its truly rabid character so cleverly, is responsible for the misplaced admiration of non-French Negroes—particularly Americans—for what they consider the more liberal French methods. It is high time, however, for this widely held illusion to be dispelled. Negroes must learn once and for all that the presence of one or more reactionary colored men in the parliamentary assemblies of the imperialist powers does not augur the independence and freedom of the colonial masses. For instance, Lord Sinha, a colored Indian, holds a seat in the British House of Lords, but he is no more concerned about the freedom of India from the British Raj than is the Negro Deputy, Monsieur Gracien Candace, concerned about the emancipation of Africa from white exploitation. Nobody has ever yet accused Monsier Candace of being an anti-imperialist. They are what Americans call: “Black-white-men.”

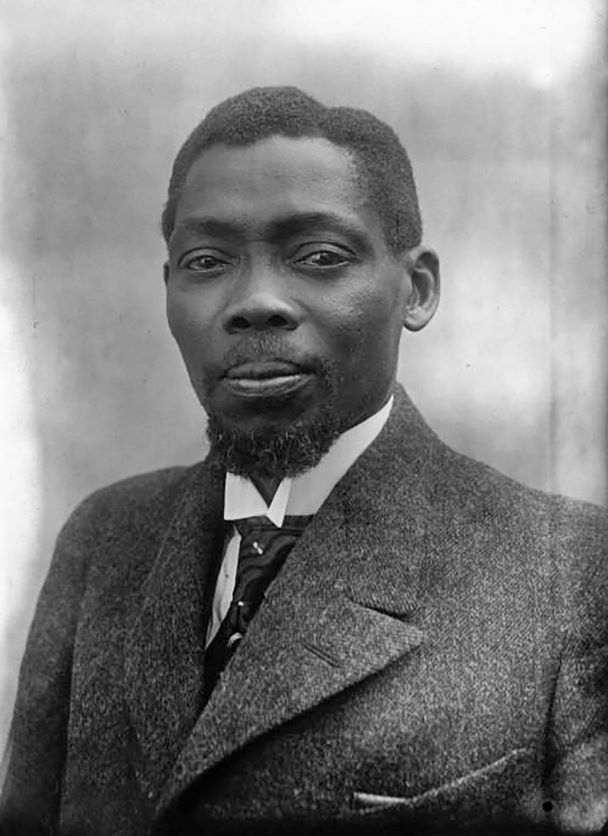

Within the French Colonial Empire the well-defined division marked out by their rulers between citizens and subjects has served to hold back the growth of the national liberation movement far behind the militant level it has achieved in the British African colonies. Not one of the Negroes purporting to represent their people in the Chamber of Deputies has ever done a single thing to advance the cause of the great masses of workers and peasants in the colonial territories from which they come. Not one trade union organization have they formed, not one cooperative—nothing. Soldiers or politicians, they have all distinguished themselves in promoting and defending the interests of their white masters, The case of Blaise Diagne, the only African born native to reach a post of any importance in the French administration, serves only too well to illustrate their true role as the hacks of French Imperialism.

Diagne’s Activity

Monsieur Diagne was the first Senegalese to be elected a deputy. During the last war he was appointed by Poincare to the temporary rank of High Commissioner and sent to Africa for the purpose of recruiting native tribesmen as cannon fodder at a time when the French Army was very hard-pressed for men. Diagne’s services as recruiting sergeant were rewarded by the portfolio of Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies under that monument of reactionary French politics, Pierre Laval, who was later to sell out the last of free Africa — Abyssinia — to Mussolini!

So identified had Blaise Diagne made himself with the interests of his imperial masters that he was sent to defend the policy of prestation or forced labor, which the French rubber plantation companies were so widely practicing under the most inhuman conditions in the French Congo, at the International Convention on Forced Labor held in Geneva in 1928. In the face of the advocacy of many white delegates from other countries for abolition of the system, Diagne maintained that it was “the sovereign right of France to impose conscription in whatever form she pleased.” He supported the system on the grounds “of the educational value of conscription to native peoples.” France has every reason to be really grateful to her black elite!

The French device of dividing her colonial populations into two different castes has succeeded admirably. For it has contented that section of intellectuals who, under the more openly repressive regime in the British colonies, are denied privileges enjoyed by their more fortunate brothers in the French territories. But while the British regime fosters resentment even among the Negro intellectual section and thus allies their interests to some extent with those of the masses in general, the French device has dulled the intellectual Negroes to the necessity for voicing the demand for national freedom and social emancipation.

The Crisis A Record of the Darker Races was founded by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1910 as the magazine of the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. By the end of the decade circulation had reached 100,000. The Crisis’s hosted writers such as William Stanley Braithwaite, Charles Chesnutt, Countee Cullen, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Angelina W. Grimke, Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Jean Toomer, and Walter White.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_crisis_1940-02_47_2/sim_crisis_1940-02_47_2.pdf