In this 1916 article Lenin challenges Piatakov’s rejection of the ‘self-determination of nations’ in the Party program because, claimed Piatakov, it gave rise to social-patriotism and echoed the imperialist’s ‘defense of the fatherland’ used to justify the World War.

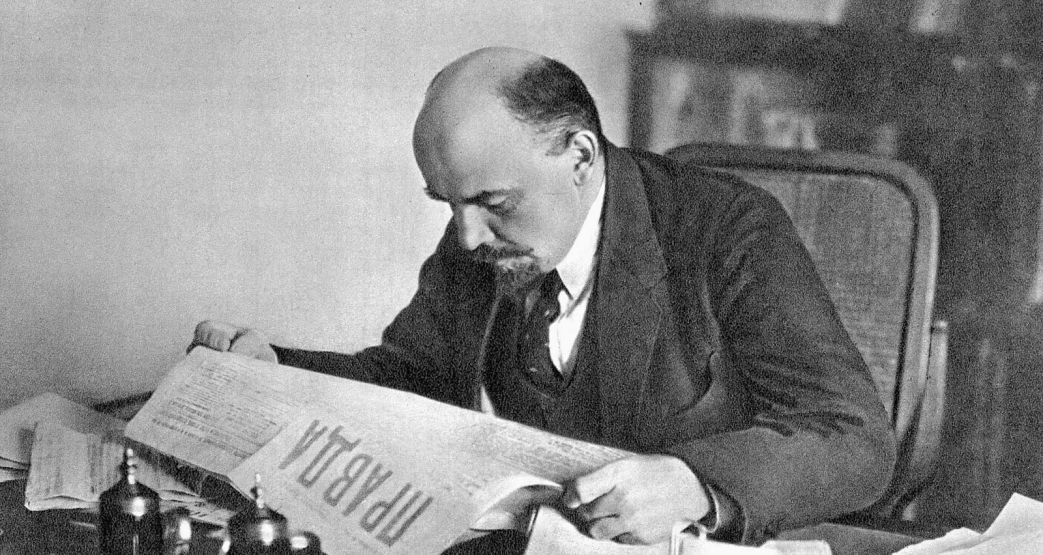

“The Defense of the Fatherland” (1916) by V.I. Lenin from The Communist. Vol. 11 No. 7. July, 1932.

(This article was written in 1916 in reply to an article by P. Kiyevsky (Piatakov) entitled The Proletariat and the Right of the Nations to Self-Determination in the Epoch of Finance-Capital.

KIYEVSKY is convinced, and wants to convince his readers that “he is in disagreement” only with the right of nations to self-determination, with paragraph nine of our Party program. He tries with much heat to rebut the accusation that he has made any fundamental retreat from Marxism in general on the question of democracy, that he is a “traitor” (the poisonous quotation marks are his own) to Marxism on any basic issue. But the fact of the matter is that so soon as he starts giving vent to his disagreement, pretending it is only about a partial or special question, so soon as he comes with his arguments and objections, etc., it turns out that he is deviating from Marxism right along the line. Let us take paragraph C (Section 2) in his article.

“This demand (that is to say, the self-determination of nations) leads directly (!) to social-patriotism”—so our author pronounces, and explains that the “traitorous” slogan of defence of the fatherland is a conclusion “drawn with absolutely (!) logical (!) justice from the right of nations to self-determination.” In his opinion self-determination is:

“The sanctioning of the treachery of the French and Belgian social-patriots who, with arms in their hands, defend their independence (the national state independence of France and Belgium)— they are doing what the adherents of “self-determination” only speak of…Defence of the fatherland belongs to the arsenal of our worst enemies…We resolutely refuse to understand how one can be simultaneously against the defence of the fatherland and for self-determination, for the fatherland and against it.”

So P. Kiyevsky writes. He has clearly failed to understand our resolutions against the slogan of defence of the fatherland in the present war. So I have to take what is written in black and white in these resolutions, and explain once more the purport of the clear Russian words.

The resolution of our Party adopted at the Berne Conference in March, 1915, and entitled “On the slogan of the defence of the fatherland” begins with the words: “The real essence of the present war consists in,” and so on.

The question at issue is the present war. It is impossible to say this more clearly in the Russian language. The words, “the real essence,” show that it is necessary to distinguish the apparent from the real, the superficiality from the essence, the phrase from the fact. In the present war the phrase “the defence of the fatherland” falsely makes out the imperialist war of 1914-16—a war for the partition of colonies, for the acquisition of foreign lands, etc.—to be a national war. In order to leave out the smallest possibility of distortion of our views, the resolution adds a special clause on “genuinely national wars,” which “took place especially (note that ‘especially’ does not mean exclusively) in the epoch from 1789 to 1871.”

The resolution explains that “at the basis” of these “genuinely” national wars, “was a long process of mass national movements, of struggle with absolutism and feudalism, the overthrow of national oppression.”

That is quite clear? In the present imperialist war, which has been engendered by all the conditions of the imperialist epoch, that is to say, it has not appeared accidentally, it is not an exception, it is not a deviation from the general and typical, the phrases concerning the defence of the fatherland are a deception of the people, for this war is not national. In a genuinely national war the words “defence of the fatherland” are in no way a deception, and we are in no way against it. Such (genuinely national) wars occurred “especially” during the years 1789 to 1871, and the resolution, while not by a single word rejecting their possibility even today, explains how a genuinely national war has to be distinguished from an imperialist war disguised by pseudo-national slogans. For this special purpose of distinguishing, one has to consider whether “at their basis” lies a “long process of mass national movements,” “the overthrow of national oppression.” In the resolution on “pacifism”? it says directly:

“The Social-Democrats cannot reject the positive importance of revolutionary wars, i.e., not imperialist wars but such as were conducted for example (note that “for example”) from 1789 to 1871 as struggles to overthrow national oppression.”

Could the resolutions of our Party adopted in 1915 speak of national wars, examples of which occurred from 1789 to 1871, and point out that we do not reject the positive importance of such wars, if such wars were not recognized as possible today also? It is clear that this could not have been so.

The brochure of Lenin and Zinoviev, Socialism and War, is a commentary to i.e., a popular explanation of, the resolutions of our Party. On page five of this brochure is written in black and white that:

“Socialists have recognized and still recognize the legality, the progressiveness, the justice of defence of the fatherland or defensive wars only in the sense of the “overthrow of an alien national oppression.””

The example is quoted of Persia against Russia and similar cases, and the brochure goes on:

“These would be just and defensive wars irrespective of who was the first aggressor, and every socialist would sympathize with the victory of the oppressed, the dependent states deprived of full rights as against the oppressor, enserfing, depredatory “great” powers.”

The brochure appeared in August, 1915, and was published in German and French. P. Kiyevsky knows it well. Not once has either he nor anyone else made objections to us either against the resolution on the slogan of defence of the fatherland, nor against the resolution on pacifism, nor against the elucidation of these resolutions in the brochure. Not once! We may ask, are we slandering Kiyevsky in saying that he has completely failed to understand Marxism, when this writer, who, since March, 1915, has made no objection to our Party’s views on the war, now, in August, 1916, in an article on the self-determination of nations, i.e., in an article ostensibly on a sectional question, reveals an astonishing misunderstanding of the question in general?

P. Kiyevsky calls the slogan, “the defence of the fatherland,” “traitorous.” We can calmly assure him that any slogan is, and always will be, “traitorous” for those who mechanically repeat it, without understanding its significance, not thinking on the matter, restricting themselves to a memorization of the words without an analysis of their sense.

What is the “defence of the fatherland,” speaking generally? Is it some scientific conception from the realm of economics or politics or something of that kind? No! It is simply the most current, generally used, sometimes simply Philistine, expression, connoting the justification of the war. Nothing more, absolutely nothing! The “treachery” here can only be that the Philistines are capable of justifying any war, by saying: “we are defending the fatherland,” whereas Marxism, which does not stoop to such Philistinism, demands an historical analysis of each separate war, in order to determine whether that war is progressive, serving the interests of democracy or the proletariat, and is in this sense justifiable, right, and so on.

The slogan of defence of the fatherland is purely and simply a reactionary petty bourgeois justification of war, through the inability historically to analyze the sense and significance of each separate war.

Marxism gives such an analysis, and says: if “the real essence” of the war consists, for example, in the overthrow of foreign national rule (which was especially typical of Europe in the years 1789-1871) that war is progressive on the part of the oppressed state or nation. If the “real essence” of the war is the partitioning of colonies, the sharing out of the spoils, the despoliation of foreign lands (such is the present war) then the phrase “defence of the fatherland” is a “direct deception of the people.”

How is the “real essence” of a war to be found, how is it to be determined? War is the continuation of politics. It is necessary to study the politics of the period before the war, the politics leading to and causing the war. If it was imperialist that is defending the interests of finance capital, plundering and oppressing colonies and foreign countries, then the war arising out of that policy is an imperialist war. If the policy was one of national emancipation, i.e., expressing the mass movement against national oppression, then the war arising out of such a policy is a war for national liberation.

The Philistine does not realize that war is a “continuation of politics” and so he restricts himself to the remark, “the enemy attacked,” “the enemy invaded my country,” not realizing what the war is being waged for, and by what classes, on account of what political end. Kiyevsky stoops completely to the level of such Philistinism, when he says that the Germans occupied Belgium, which means, from the point of view of self-determination, that the “Belgian social-patriots are right”; or, that the Germans have occupied part of France, which means that “Guesde can be satisfied,” for “the war is reaching territory inhabited by this people” (but not a foreign one).

For the Philistine the important question is, “Where are the armies, who is now winning?” For the Marxist the important question is: What is the given war being waged about, irrespective of who, at the moment, is victorious?

What is the present war being waged about? That is indicated in our resolution (which is based on the policy of the warring countries, the policy which they carried on for decades before the war). Britain, France and Russia are fighting for the retention of the colonies they have stolen, for the pillage of Turkey and so on. Germany is fighting to win colonies for itself and itself to pillage Turkey and so on. Let us assume that the Germans even take Paris and Petersburg. Will the character of the present war be changed thereby? Not in the least. The purpose of the Germans (and, what is still more important, the policy realizable through the victory of the Germans) will then be the taking of colonies, hegemony in Turkey, the taking of alien national regions, Poland, for example, but not in the least the establishment of an alien national oppression over the French or Russians. The real essence of the present war is not national, but imperialist. In other words: the war is being waged not because one country is overthrowing national oppression while the other is defending it. The war is being waged between two groups of oppressors, between two robbers over the question of who shall divide the spoils, who shall pillage Turkey and the colonies.

In brief: war between imperialist great powers (i.e., powers oppressing a whole series of foreign peoples, entangling them in the nets of dependence upon finance-capital and so on) or a war in alliance with such powers is an imperialist war. Such is the war of 1914-16. “Defence of the fatherland” is a deception in this war, it is its justification.

War against the imperialist, i.e., the oppressing powers, waged by the oppressed (for example, the colonial peoples), is a truly national war. Such a war is also possible today. The “defence of the fatherland” on the part of a nationally oppressed country against the one nationally oppressing it, is not a deception, and socialists are in no way against the “defence of the fatherland” in such a war.

The self-determination of nations is the same as the struggle for complete national liberation, for complete independence, against annexations, and socialists cannot reject such a struggle—in any of its forms, right down to insurrection or war—without ceasing to be socialists.

P. Kiyevsky thinks that he is fighting Plekhanov; for Plekhanov pointed to the connection between the self-determination of nations and the defence of the fatherland! Kiyevsky believed Plekhanov in thinking that this connection was really such as Plekhanov represents it. After thus putting his trust in Plekhanov, Kiyevsky took fright and decided that it is necessary to reject self-determination in order to save oneself from Plekhanov’s conclusions…A great confidence in Plekhanov, a great fright also, but not a trace of reflection as to where Plekhanov had gone wrong!

In order to represent this present war as a national one, the social-chauvinists refer to the self-determination of nations. There is only one correct struggle with them: that is to point out that this struggle is not over the liberation of nations, but to decide who of the great despoliators shall oppress the nations the most. To reach the conclusion that it is necessary to reject a war really carried on over the liberation of a nation results in the worst caricature of Marxism. Plekhanov and the French social-chauvinists refer to the republic in France in order to justify its “defence” against the monarchy in Germany. If we argue as Kiyevsky argues, then we ought to be against a republic or against a war which really is waged for the maintenance of a republic! The German social-chauvinists refer to the universal franchise and the compulsory education of all in Germany, in order to justify the “defence” of Germany against tsarism. If we argue as Kiyevsky argues, then we must either be against universal franchise and compulsory education, or else against a war really carried on in order to defend political liberty from attempts to take that liberty away!

Until the war of 1914-16, Karl Kautsky was a Marxist, and a whole series of important works and pronouncements by him will remain forever examples of Marxism. On August 26, 1910, Kautsky wrote in Die Neue Zeit on the question of the approaching and threatening war:

“In a war between Germany and England the question will be not democracy but world hegemony, that is to say, the exploitation of the world. That is not a question in regard to which the social-democrat should stand on the side of the exploiters of their own nation.”

There you have an excellent Marxist formulation, completely agreeing with our views, completely unmasking the present Kautsky, who has turned from Marxism to the defence of social-chauvinism (we shall return to this formulation) and quite definitely explaining the principles of the Marxist attitude to war. Wars are the continuation of politics; consequently, once there is a struggle for democracy, a war over democracy is also possible; the self-determination of nations is only one of the democratic demands, in no way differing in principle from the others. “World Hegemony” is, to put it briefly, the content of the imperialist policy of which the imperialist war is the continuation. To reject the “defence of the fatherland,” i.e., participation in a democratic war, is a stupidity which has nothing in common with Marxism. To whitewash the imperialist war by applying the conception of the “defence of the fatherland” to it, i.e., by representing it to be a democratic war, is equivalent to deceiving the workers, and passing over to the side of the reactionary bourgeoisie.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v11n07-jul-1932-communist.pdf