William Z. Foster writes from Italy where he witnessed the violent blackshirt assaults on the workers movement that came after the Biennio Rosso revolutionary wave.

‘Fascisti Against the Workers in Italy’ by William Z. Foster from The Toiler. Vol. 4 No. 193. October 22, 1921.

Turin, Italy, Aug. 28, 1921. With the passage of the months it is becoming ever clearer that Italian labor men made a serious mistake in their handling of the famous metal workers’ strike last September, and one that has sadly demoralized their movement and thrown it crippled to the white terror.

It was indeed a fateful day when the Executive Committees of the Socialist Party and the General Confederation of Labor met in joint session to determine their course of action in the acute situation caused by the metal workers’ strike. The whole Italian working class was in a revolutionary mood. The metal workers had seized the plants all over the country. The peasants were confiscating the land. Red flags were flying from municipal buildings in a hundred cities. All the workers were on the qui vive and ready for a final battle with capitalism. On the other hand, the bourgeoisie was almost totally unprepared. Its government was paralyzed and dared not stir. It was an historic opportunity such as may never occur again.

In this critical situation the heads of the two wings of the labor movements met. The issue was clear and clean. Should the workers make a great effort to seize political power and undertake to put socialism into effect, or should the metal workers’ strike be confined to the status of an ordinary wage struggle? It was the supreme revolutionary test of the Italian labor movement, and it found them dismally wanting. The representatives of the Socialist Party, backed by those of the metal workers’ union, were for making a revolutionary attempt, but the leaders of the Confederation of Labor opposed it. They declared that conditions were not yet ripe, and that to make an attempt at the revolution would only lead the workers to useless slaughter. They proposed instead that the crisis be utilized to establish workers’ control in every industry, the right of the workers to investigate and check up on all the intricacies of the productive organism.

The trade union leaders, headed by D’Aragona, prevailed. The motion to issue a call that was practically equivalent to revolution was voted down, and one demanding workers’ control adopted. On this basis the metal workers’ strike was settled. The men received an increase in wages. Prime Minister Giolitti expressed himself in favor of workers’ control and created a commission to study the proposition and to bring in a project for its realization. And so the great revolutionary crisis passed.

Almost instantly all Italy knew that the workers had been overwhelmingly defeated. They had given up the greatest opportunity ever presented to the working class for the sake of a miserable increase in wages wiped out soon after by the advancing cost of living, and on the promise of a crooked politician to establish a reform which has never been realized, but is still being “studied” by the commission. As for the workers, they became prey to a profound pessimism and demoralization from which they have not yet recovered. Raised to the supreme heights of anticipation by their superb effort, they saw their beloved revolution peddled for a mess of pottage, and they fell into a slough of despond which has been deepened by the industrial depression.

By the same token the capitalists have been cheered and encouraged beyond measure. When they had recovered from their first fright at being held over the revolutionary precipice, they launched a great offensive all along the line. They would take lasting revenge over their rebellious slaves, and make forever impossible the recurrence of such a revolutionary situation. One of their chief instruments in this onslaught, which is unexampled for violence and bitterness, is the organization of the Fascisti, notorious throughout the world for its atrocities.

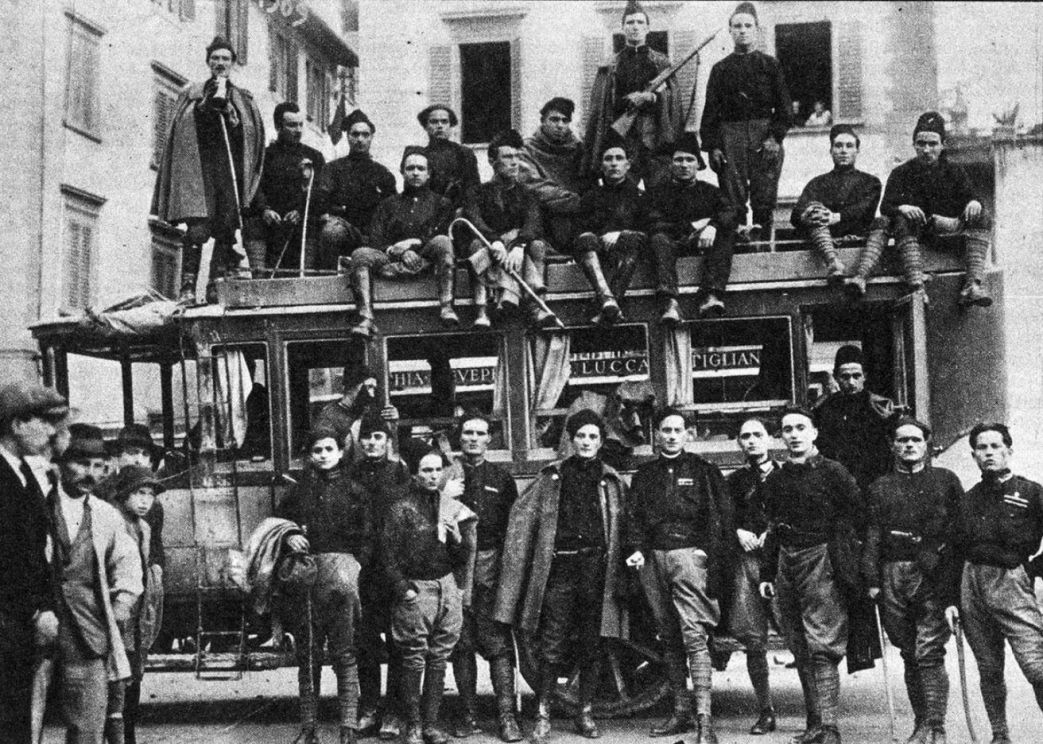

The Fascisti are a national body, with regularly organized branches in nearly all the large cities and towns of Italy. It is officially reported that their membership totals 170,000, but labor men declare it is much larger. They have elaborate headquarters in many places, and a whole battery of daily, weekly and monthly publications. The organization does lip service to a rabid patriotism, but in reality it is merely an appendage for doing the dirty work of the country’s big business interests. These exploiters finance it liberally and openly. The membership, especially the militant part of it, is made of ex-military officers, students, habitual criminals, and the hundred and one other degenerate elements who, through greed and stupidity, are always on hand to serve as white guards for capitalism. The name of the movement is taken from the bundles of rods or “fasci” the emblem of the old Roman empire, typifying the power that comes from close organization. The leading spirit is Benito Mussolini, a renegade Socialist. He is editor of Il Popolo d’ Italia, national daily organ of the Fascisti. At a recent meeting of the latter’s executive committee he was affectionately referred to as “the master and flame of our faith.” In these days when European capitalists have a particularly dastardly attack to make against the workers, they always get some so-called revolutionist to lead it for them.

The Fascisti organization is of comparatively recent growth. It originated from the scattering groups of fanatical “patriots,” a la D’Annunzio, that sprang up immediately after the close of the great war. They won their spurs in April, 1919, when, during a riot cooked up by themselves, they burned the Milan offices of L’Avanti, the revolutionary paper. The movement lingered, however, weak, inconspicuous, until after the metal workers’ strike. Then the terrified employers seized upon it as just the weapon they needed, forced it into a mushroom growth, and launched it in a deluge of blood and iron upon the devoted heads of the workers. Thus they inaugurated one of the most astonishing campaigns of bloodshed and violence in modern history.

The method of the Fascisti is calculated, organized terrorism. They aim to paralyze the workers with naked fear and to destroy every semblance of organization and independence among them. Murder, arson, rape, kidnapping, and the systematic violation of every right, human and civil, of the workers are the tools they use in their work of destruction.

A favorite tactic is the so-called “punitive expedition.” For some fancied grievance the Fascisti will decide to punish the workers in a certain town. To this end they assemble their cohorts from all the surrounding country and make an armed automobile raid in force upon the ill-fated community, shooting and beating men, women and children, and destroying working class property, until their fine patriotic instincts are satisfied. In this fashion scores of workers have been murdered and hundreds of labor temples, cooperatives, newspapers, plants, etc., sacked and burned.

The Fascisti are bold and insolent beyond imagination. They think nothing of going in a body to the homes of Socialist mayors and aldermen and forcing them to write out their resignations. Thus the Socialists have been driven from office in dozens of towns, even where they control nine-tenths of the vote and have been in power for years. The same system has been used in the unions, and cooperatives. Often the officials of these bodies are compelled at the point of a revolver to quit their posts and to turn the books and funds of the organizations over to the Fascisti, who then see to it that their own creatures are put in office. With such methods the Fascisti have gathered some remnants of organizations, literally carved out of the body of labor, and have developed their own “patriotic” trade union and co-operative movements.

Mere details in the day’s work of the Fascisti are complete suppression of free speech and assembly for the workers, ordering dealers to stop selling. revolutionary journals and compelling workers to cancel their subscriptions to them, forbidding the nomination of socialist candidates in the local elections. Thousands of these outrages have taken place all over Italy, with the burden of the storm striking the industrial north. The worst sufferers have been the smaller towns, especially in the districts where the agricultural workers are strongly organized, but even in the larger cities such as Turin, Bologna, Milan, Florence, Modena, Parma, many labor temples and other working class institutions, often the fruit of years of work, have been ruthlessly destroyed.

Far from attempting to stop this reign of terror, the government has openly aided it. Time and again its police and soldiers have joined hands with the Fascisti in their depredations, and then arrested and punished the outraged workers. They see to it that the latter, under the severest penalties, are kept unarmed, while the Fascisti go about openly everywhere armed to the teeth. This attitude of the government explains why the minority of Fascisti are able to tyrannize over the majority of workers. The big Socialist fraction in the Chamber of Deputies has complained bitterly about the Fascisti outrages but in vain. The whole situation indicates the collapse of parliamentarism.

In the face of the terror the attitude of the workers’ organizations has been one of passive resistance. Stating that Fascism is an after-war phenomenon that must soon pass away, the leaders have counselled the rank and file to hold firm and not to allow themselves to be provoked into acts that would call forth still greater violence. Where here and there the workers have fought back against their tormentors it has usually resulted only in added “punitive expeditions” by the Fascisti. Militants whom the latter know to be in active opposition to them are often called to their doors in the middle of the night, usually on the pretense that it is the police knocking, and given a bullet in the brain. Or they have been spirited away from their families and ordered never to return.

A peace pact has been drawn up between the workers and the Fascisti within recent weeks, as is generally known. Various reasons are ascribed for this. Some people say that it was made because the saner elements among the Fascisti fear that the present excesses will inevitably result in similar ones by the workers once they rouse themselves to action again. Others declare that the big employers refuse longer to meet the tremendous expenses incurred by the Fascisti and are insisting upon retrenchment. Whether the fact will produce even a semblance of peace remains to be seen. Certainly the expected peace has not arrived yet. A few days ago just as I was passing through that section, a serious clash occurred in the Parma district. A body of Fascisti attacked some local Communists and carried home two dead for their trouble. In Milan I found a number of police drawn up to “protect” the splendid big local labor temple from possible Fascisti attacks, and in Bologna, before the office doors of the famous Italian Railroad Workers’ Union, there were stationed several soldiers for the same purpose.

The peace pact has brought about a crisis in the ranks of the Fascisti and is threatening to split them. A powerful element, consisting of those fanatics who are for utterly destroying everything of a labor character, look upon the pact as a betrayal of the interests of their beloved Italy, and want war to the knife against the hated Socialists. Their flaming posters, couched in most violent language and calling upon the faithful Fascisti Italiani di Combattimento to rally against the internal enemy, are plastered literally everywhere in many northern Italian cities, I never saw the like of it for a poster campaign.

These dissentient elements have raised so much disturbance that Mussolini, Marsiglio, Rossi and Farinacci, all prominent officials of the organization, have handed in their resignations. Desperate efforts are being made to prevent a split, but opinion is divided as to the outcome.

As a consequence of their leaders’ timidity in the critical September days, the Italian workers’ organizations have suffered morally and physically. To what extent this is true I could not learn, but that it is considerable can be readily seen from events among the metal workers themselves. These militant workers have lost their shop committees, the bodies that executed the famous occupation order, and it is only a few months since they broke ranks in a lockout at the famous Fiat works and flocked back to work upon the employers’ terms. From a near revolution to a lost strike over a petty grievance is a sad come-down in the course of a few months. Prominent Italian labor men assure me, however, that despite the depression of the workers and the attacks of the employers, the trade union movement as a whole has not been seriously injured. I hope this is true.

The great lesson of the present Italian situation is that the labor movement cannot safely monkey with the revolutionary buzz-saw. The seizure of the metal works was a revolutionary act. Either it should have been followed by a general drive of the workers for political power, or it should not have been ordered in the first place. But it was ordered, the necessary follow-up moves were not made, and the inevitable debacle resulted. Unless I am mistaken D’Aragona and the other trade union leaders responsible will soon have to give place to men who will not flinch when the next great crisis comes.

The Toiler was a significant regional, later national, newspaper of the early Communist movement published weekly between 1919 and 1921. It grew out of the Socialist Party’s ‘The Ohio Socialist’, leading paper of the Party’s left wing and northern Ohio’s militant IWW base and became the national voice of the forces that would become The Communist Labor Party. The Toiler was first published in Cleveland, Ohio, its volume number continuing on from The Ohio Socialist, in the fall of 1919 as the paper of the Communist Labor Party of Ohio. The Toiler moved to New York City in early 1920 and with its union focus served as the labor paper of the CLP and the legal Workers Party of America. Editors included Elmer Allison and James P Cannon. The original English language and/or US publication of key texts of the international revolutionary movement are prominent features of the Toiler. In January 1922, The Toiler merged with The Workers Council to form The Worker, becoming the Communist Party’s main paper continuing as The Daily Worker in January, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/thetoiler/n193-oct-22-1921-Toil-nyplmf.pdf