‘A Visit To Leavenworth’ by Eugene Lyons from Workers World (Kansas City). Vol. 1 No. 31. October 31, 1919.

Three government cages in a radius of about a mile, and political prisoners in every one of them; such is the town of Leavenworth.

The County Jail, little more than an iron-girded cottage, holds captive eight of the group of thirty-odd awaiting dubious justice under the Wichita indictment. With them is a good-natured little Italian, Pietro Pieri, lately sentenced for a mythical threat to kill the President and his son-in-law, Mr. McAdoo, For a potential murderer, he is incongruously sweet-tempered. I almost wished, for the sake of abstract symmetry of course, that he might brace up, harden his kindly but prison-worn features, and dash a stiletto in one realization of his newly-acquired dignity-that of assassin-to-be.

The U.S. Penitentiary looms magnificent upon the horizon; a palatial structure of heroic proportions, stone walks winding like ribbons among carpet-like lawns of fading green, brightly painted out-houses resting on the grass. And all this confined by a wall of barbed wire, reinforced at intervals by gun-bearing guards. The prison proper has two white rectangular wings connected by a loud red brick walled passageway. The wings of the penitentiary are spotted with the dismally monotonous prison perforations across which run the black bars, bars, bars. Within are tiers upon tiers, of dungeons, in scores of which lie the true and tried spokesmen of a happier world. The prison atmosphere inside is as a nightmare against the gay green sunshiney world that is shut out. Here are the Chicago group of I.W.W.’s jailed with so much childish eclat by Judge Landis. Here are the California workers who accepted capitalist justice with a silent disdain that chilled the masters. Here are leaders of Socialist thought, including the dauntless group of Kansas City workers who purchased a militant newspaper with their liberty. Some distance further is the Military Prison at Fort Leavenworth. It brings to mind poignantly the atrocities committed upon those who refused to sell their souls for a mess of pottage, the conscientious objectors. It is among hills and valleys replete with charms that young men were tortured and thrown into rat-ridden holes for their untinctured idealism.

These contrasts and paradoxes, the reality/of both beauty and the beast, he attractive country and the ugly works of man, dominate one’s senses. It was my first visit to the prison town. An electric railway leads from Kansas City to Leavenworth. Its course winds through farmlands, past uncultivated sections, now races with a busy brook, now cuts through a village. It passes the very door of the County Jail.

It is an informal jail. I expressed my wish to see the I.W.W.’s, and was announced unceremoniously so that every inmate could hear me. From every corner of the cage came prisoners; some from their cells, where they were reading some abstruse book or writing a letter, their only contact with their former life; others left the circle where they were preaching their ideas to new acquaintances. Nine in all clustered about me to get a whiff of the unbound world. Most of them have been in jail continuously for two years. The nine confined in this jail, which is considered the most wholesome among the county jails of the state, are C.W. Anderson, F.J. Gallagher, O.E. Gordon, Morris Hecht, P.J. Higgins, Fred Grau, Paul Maihak, Ernest Hening, George Wenger, and Pietro Pieri.

The most striking fact manifest in their conversation is a thoroughgoing acquaintance with current labor news. Most of the labor papers reach the jail sooner or later and are thereupon devoured by news-hungry political prisoners. I had looked forward to conveying to them certain, pertinent developments in the movement, but instead remained to listen. Another impressive effect of the long confinement and the consequent brooding over capitalist injustice is a profound optimism as to the future. It is their belief, by and large, that such colossal iniquity cannot long endure; that the people will in the near future arise in their wrath to overthrow a false industrial scheme.

In the federal prison I arranged to see Charles Ashleigh, Harrison George, and Dan Buckley, individually: And for the three interviews the warden permitted precisely thirty minutes. Probably he has never had a real talk with any one of them or he would have realized the utter impossibility of breaking away from them of their type, who hold you captive by the strength of their personality and the invincibility of their spirits. I talked to Ashleigh, spent a few minutes with George and to my astonishment the time allotted was over.

Not a word of complaint crossed their lips. The determined optimism, the strange cheerfulness were the more overwhelming in those surroundings. They recounted stories of prison life, inquired about friends on the outside.

I left with this idea impressed upon my memory in big burning letters, although it had not been expressed in so many words by the imprisoned men: that the best and most appreciated contribution we on the outside can make towards the welfare of our imprisoned comrades is to write them often, cheerful newsy letters.

The persecution visited upon the members of the Industrial Workers of the World does not cease when the prison door has clanged upon them. Several occurrences of the last few weeks will make this clear:

The bail for Charles Ashleigh was being raised by a woman in Los Angeles, California. She was indeed well on her way towards the needed amount when she was informed by individuals representing themselves to be Federal agents that Ashleigh would be released on parole, and that her efforts in his behalf were consequently superfluous. Being a middle class, well-meaning woman, she accepted these representations with a naive credulity as the gospel truth. The letter she wrote to the prisoner would be laughable if it were not a messenger of more imprisonment for Ashleigh. She congratulated him upon his parole, and informed him that she had stopped work on the bond.

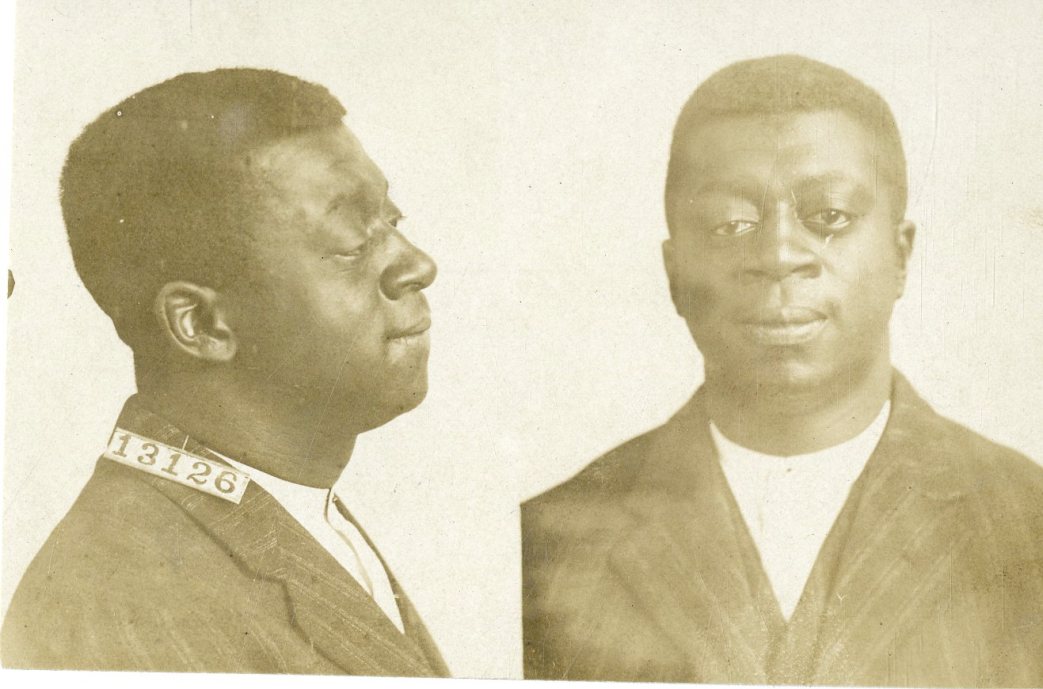

Two occurrences stirred the prison about the same time. I.W.W.’s figured in both. First, while one of the California group was having some words with a guard, somebody struck the guard from behind. An official inquiry failed to reveal the guilty man. The I.W.W. having been face to face with the guard was thrown into the “hole” and according to rumors, has been manhandled. Second, a colored prisoner–not an I.W.W.–called one of the guards up to the top tier of cells. Somehow an argument arose, and the negro in a fit of temper struck the guard and was about to throw him down over the railing–a sure death. Ben Fletcher, the only negro I.W.W. In the jail rushed to the scene. At the risk of his own life he intervened and saved both the guard and the prisoner, who would have suffered the death penalty in the event of a fatal fall by the guard. The significant fact is that the first event is flaunted and punished, while the heroism of Fletcher is unmentioned and unrewarded.

Both Harrison George and Charles Ashleigh work in the office of the prison. Since his imprisonment George has learned touch typewriting and even stenography, so that now he has made himself indispensable in the penitentiary. I mention this as indicative of the unwilling recognition the authorities are obliged to give to the circumstances that the political prisoners after all are not criminals–they suffer the penalty for daring to be the protagonists of a new thought. At least half the teachers in the improvised school system in the prison are members of the Industrial Workers of the World.

While I was talking to George, one of the Browder brothers and Sullivan were shown in. Several people had come to visit them, among the group Marguerite Browder. The situation was really interesting. The party in the room was almost entirely made up of radicals.

Over the room where visitors meet the prisoners is the sign “Audience Room.” And the audience is always there in the form of a guard who listens to conversations and makes notes.

The Workers World, published weekly in Kansas City, Missouri during much of 1919 was a mix of regional and national working class news, international socialist events, and the growing fights within the Socialist Party. It was one of many left-wing Socialist Party journals inspired by the Russian Revolution to emerge. Edited alternatively by future Communist Party leaders James P Cannon and Earl Browder, The Workers World ceased publication in November, 1919 as writers and readers moved on to build the Communist movement and its early parties.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workersworld/WW31.pdf