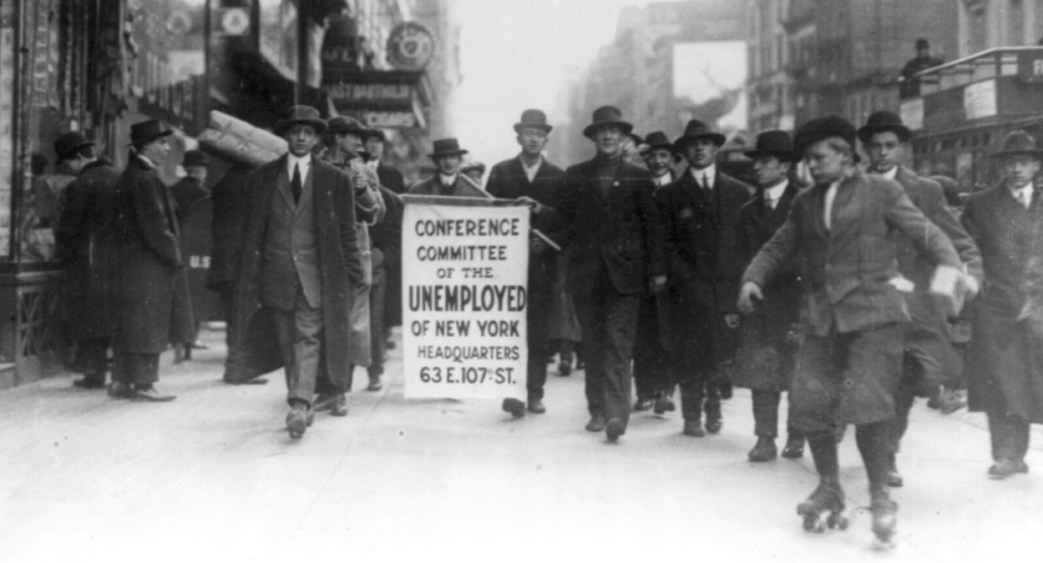

A series of I.W.W. organized unemployed demonstrations in New York’s Union Square were routinely assaulted by police in 1913-1914. Legendary labor journalist Mary Heaton Vorse reports from the scene.

‘The Police and the Unemployed’ by Mary Heaton Vorse from New Review. Vol. 2 No. 9. September, 1914.

“Not even the courts have the power of inflicting corporal punishment. It is repugnant to the whole spirit of our civilization. How much more outrageous it is that police officials, blind with rage, should inflict such a beating upon a citizen.”

Editorial, New York Sun, May 12, 1914 “Nothing breeds anarchy faster than a lawless police force.”

This year has been marked in New York by numerous clashes between the police and various radical groups, beginning with the arrest of one hundred and ninety homeless men who on March 4th sought shelter in the church of St. Alphonsus and continuing up to this present moment.

One of the disturbances which aroused the most comment occurred in and outside the Calvary Baptist Church on Fifty-seventh Street. When the Rev. Bouck White arose and attempted to speak in this congregation he was at once thrown out of the church in a violent manner, and his followers so mishandled as to give rise to many editorial comments, of which the above are samples.

There was a wave of public indignation at the action of the police. So sane and balanced a man as Mr. Amos Pinchot in his open letter to Mayor Mitchel said:

“Nothing that Mr. White or his friends might have said in regard to the Christianity of Calvary Church and of the gentlemen who support it, or of the standards of Christianity in this city, could possibly have amounted to so scathing an indictment as the furious assault which the city’s officials and the frock-coat phalanx of Calvary piously indulged in.”

Mr. White, however, was sentenced to six months in the work- house, as was Milo Woolman, who at the time of his arrest was reading aloud to his wife from the Bible.

This workhouse Mr. Pinchot refers to as a “medieval jail where conditions of overcrowding confine six to ten men for fourteen hours a day in a small, foul cell.” He refers to it further as “a sink into which the unfortunate refuse of the city is cast to rot and fester.”

There has been criticism of Mr. White’s act in coming uninvited to the church, but the public, as a whole, even when not agreeing with his methods, have done him the credit of believing him sincere and full of desire to shed light on the darkness of the calamitous events in Colorado, which culminated on April 20th in the burning of the tent colony at Ludlow, where two women and eleven children were burned to death.

When you grant a man is sincere while not agreeing with his methods of propaganda you show that you have given his conduct enough thoughtful consideration to make some attempt to find out why he acted as he did.

I do not believe that the public has been trying as earnestly to find out what lay behind other radical demonstrations of this winter. To anyone who closely followed these demonstrations there was nothing surprising in the actions of the police in the Calvary Baptist Church.

On the same day that newspapers were commenting on the meaning of Mr. White’s arrest and the treatment of his supporters, an item appeared in the papers which stated that Joe O’Carroll, who had been conspicuous in the unemployed demonstrations, was in the hospital for an operation on his scalp, made necessary by police brutality.

Later I saw another item saying that Arthur Caron1 was just out of hospital, where he also had been for an operation for injuries received at the hands of the police. He and O’Carroll had been arrested and beaten–Caron to unconsciousness–upon April 4th as they were peacefully leaving Union Square.

Undoubtedly the policemen believed that public sentiment would uphold them—and they would have been right had not the case been so flagrant. The demonstrations of the unemployed were unpopular. It is profoundly disquieting for people comfortably off to witness a great mass of destitute people and their sympathizers walking up Fifth Avenue, assembling in parks and squares and otherwise making their presence felt in the city. So the policemen were probably deeply surprised and hurt when public opinion, Magistrate Freschi, and their superior officers united in condemning their act.

No one has condemned the editorials which have repeatedly called upon the police to exceed their authority and to use violent and repressive measures upon the unemployed and their sympathizers gathered together in the public squares.

This was the second time O’Carroll and Caron had been arrested, although the courts themselves, which have not been inclined to look upon the demonstrations with too lenient an eye, have acquitted them of disorderly acts.

This is but one of many times during the past months that the police have abused their authority and that their attitude has been curiously at variance with the openly expressed attitude of the city administration. Indeed, we have had a curious situation in New York, a Mayor who in his public statements has insisted that the unemployed, the I.W.W., and the Anarchists, should have the right of assembly and free speech, a Police Commissioner who has urged moderation upon the men under him, combined with oppressive and irritating acts on the part of the police.

How irritating has been the attitude of the police and how without provocation they have shown brutality of speech and violence of action, it would be hard for anyone to realize who has not himself been an eye witness.

When one considers how many demonstrations there have been this winter in our squares and on our streets, one must acknowledge that the actual acts of disorder have been few. That there have been no more acts of actual disorder is not the fault of the police, and I prefer to give the account of two of the witnesses on two such occasions.

The first time Joe O’Carroll was arrested was in Cooper Union where the Socialists had held a meeting to discuss unemployment. He and the Rutgers Square group of unemployed were present, his followers called for him, and permission was given him to speak at the end of the programme. The programme being ended the meeting was announced closed. O’Carroll rose to speak, trouble ensued, and he was arrested.

This is an account of what followed afterwards, made by Mr. Harvey P. Vaughn, a worker in the University Settlement at 184 Eldridge Street. The attention of the Mayor was brought to this statement:

“After a meeting in Cooper Union held by the Socialists to dis- cuss unemployment, a number of people gathered in the open space at the south of Cooper Union. The crowd was quite orderly, and outside of the fact that the speakers called upon the people to protest against O’Carroll’s arrest, there was nothing out of the ordinary in their speeches.

“I heard a noise of trampling feet and some shouting, but not unusually loud shouting, coming from the direction of the southeast corner of Cooper Union, and on looking that way saw a large number of plain-clothes men and uniformed officers rushing into the crowd in what was in general the shape of a wedge. As they split the crowd open, making way toward the center where the speakers were located, they used their fists in hitting people, their hands and arms and elbows in shoving and pushing them, and their clubs in striking them.

“The crowd were taken completely by surprise and tried to give way to this onslaught, but many were not able to get out of the way quickly enough, and of these I saw Lieut. Gegan and Lieut. Gildea catch one and strike him with their fists simultaneously. The man fell and crawled away as quickly as he could, the officers striking at him as he left.”

Mr. Vaughn goes on with an account of specific instances, with the names of men beaten by the police. Some were so badly hurt that they were sent to the hospital, and he concludes:

“I have lived in mining districts and both in the east and in the north have seen disorderly crowds handled by officers, but I have never seen any brutality that equaled the kind that was used in driving this small crowd of people away from Cooper Union Square Thursday evening. I fully expected every newspaper to call for immediate and severe punishment of the officers responsible, but since I have not seen one word in regard to it, I have taken this means of letting it be known to the proper authorities.”

Mind you, this clubbing which occurred on Cooper Square was not mentioned in a single New York paper.

On April 4th the unemployed and a group of sympathizers from the Ferrer School had intended to hold a demonstration in Union Square, but finding the Central Federated Union had planned a protest meeting concerning the Colorado matter, they deferred their meeting until April 11th. The crowd at no time showed any disorder, but as the unemployed started away the mounted police rode them down. Women were clubbed, people were forced to take refuge on the steps of houses to get out from under the horses’ feet. A scene of the utmost disorder reigned. Yet investigation failed to show any reason at all for this action on the part of the police.

This is Arthur Caron’s statement of what happened to him and to O’Carroll:

“I started to leave Union Square a few minutes after the introduction of the first speaker, and with a young lady I walked through the park. As we walked down by Fifteenth street I saw the police with upraised clubs rushing the crowd back.

“I ran across the street and saw Joe O’Carroll covered with blood, the blood streaming from wounds in his head, surrounded by uniformed and plain-clothes men with clubs and black jacks upraised. I saw Becky Edelson standing over Joe trying to shield him from the blows of the police.

“I tried to get to her, but the police rushed the crowd back and I was driven with them into the street. The police dragged Joe up Fourth avenue toward Sixteenth street and I followed with the crowd.

“Near Sixteenth street, a plain-clothes man rushed at me with his shoulder lowered, striking me in the shoulder and spinning me around. At the same moment I was struck by some one with a club or black jack in the back of the head and two plain-clothes men grabbed me. I looked around to see who hit me and a plain- clothes man hit me on the left side of the head with his black jack. Another officer grabbed my right arm and twisted it up behind my back, at the same time pushing my shoulder and I got a smash on the shoulder with a policeman’s club. The blows came from behind. I cried out, “For Christ’s sake, stop hitting me!” and 1 got another bang with a black jack on the back of the head and one of the officers said, “You—– take that.”

“I was so dazed by the blows that I was helpless. As I was dragged along they kicked me in the calves of both legs and I was either kicked or struck with a club in the thigh.

“I was taken to an automobile that was waiting and in it I saw Joe O’Carroll sitting beside Officer No.—-. I was thrown into the automobile and as I stumbled in Officer—–said, “You we’ve got you now,” and struck me in the face. I fell to my knees with my head in Joe’s lap. I tried to get up but got another crash in the face, and Officer No.—-said, “You—-lie still.” I raised my head again and he struck me in the face, crushing in the right side of my nose, and then I was struck again on the back of the head. I don’t know who hit me then. The next thing I knew I was dragged out of the automobile and into the police station.”

After giving in detail some of the threatening and abusive con- versation of the police in the police station, Caron says:

“They continued to make jeering and insulting remarks about us until we were taken back to the anteroom and then into the court. For instance, when O’Carroll, Caron and Wolfe began talking in French, Officer No. told them threateningly to shut up and also said to O’Carroll, “It ain’t too late yet to give you a G-d- good beating like we gave this fellow here,” pointing to Caron.

Magistrate Freschi, in acquitting O’Carroll and Caron, recommended that their beating by the police be looked into and the offenders punished, but this was not done, because both the young men beaten and the group of people whom they represented felt that punishing individual policemen for acts of violence accomplished nothing and such an act would savor of revenge and retaliation, perpetuating the system against which they protested.

The next time the radical group assembled in Union Square was Easter Saturday. As there had been great disorder, of police maxing, on the previous Saturday, Commissioner Woods had been urged to see how the crowd would act with only the usual number of police on duty. Afterwards the papers called the afternoon a tame one. They said nothing happened. Opinions differ about that. Some people thought a great deal had happened, for the extreme wing of the New York radical group packed Union Square to see the unemployed establish their right of assembly and of free speech–the same group who had been ridden down and clubbed the Saturday before.

Over this crowd was a nameless feeling of suspense. Moreover, everyone knew that besides the visible police there were stowed away, in empty lofts around, hundreds of men ready at a moment’s notice to rush the trouble makers.

The crowd began ebbing out. From a dense, uniform mass it broke up into little groups surrounding isolated speakers. Waiting for the end, I fell into conversation with a policeman. “It’s almost over,” I said, “isn’t it?”

“It ain’t begun yet,” he answered, “they’ll make trouble for us the last thing. It was late last Saturday when they started up. Them I.W.W.’s always make trouble when they get together.” He spoke with conviction.

“Why are you so sore at them?” I asked him.

“Sore?” he repeated, “why wouldn’t we reserves be sore? Talk about your eight-hour day! We reserves are on night duty and they’ve been chewing the rag from one o’clock until now it’s near seven. I’m losing my sleep–that’s why I’m sore. And that’s why there are a hundred men in that hall,” he jerked his hand, “who’re sore! And another couple o’ hundred scattered around who’re sore! Them I.W.W.’s give us an awful lot of extra work.” “I’ve reported lots of meetings in Union Square,” I told him, “meetings of Socialists, meetings of Suffragists, where there was more what you might call ‘disorder’ in the crowd than there has been to-day, but you aren’t sore at them.”

“Oh, Socialists and Suffragists–they’re respectable. We know what to expect from them. But these fellows are out for a scrap, that’s all they’re out for. They don’t know what they want.” “They’d say they knew what they wanted.”

“Well, I’d be glad if they’d tell me,” he answered.

I explained the I.W.W. commonplaces. “What they want is to organize industrially. They want industries to be organized all together in one union, instead of trade by trade.”

“Well, now,” said he, “that sounds like sense! That’s the first word of sense anybody ever said to me about them I. W. W.’s. This is the first time I ever knew they wanted anything except to make trouble. Is that all they want?” he inquired. He was honestly astounded.

“Well, after that, they say they’d like to have the working men own the industries themselves, and get the profit of their labor for their children’s education and for their own good.”

“A sort of plan to benefit the working classes?” said my friend. “Well, now, you surprise me! It’s a kind of Labor Party you might say, with ideas in it something like the Socialists? Now, I don’t believe there are ten men who’ve been put on duty to look after these meetings that ever heard a word like this. I guess everybody thought just what I thought that they’d no idea but to kick without knowin’ what about and make trouble generally.”

He and the hundreds of men around the Square had been put on duty to keep in order an indefinite something called I.W.W.—a trouble-making monster, obscurely potent with the mob. He and hundreds of others were standing on their toes ready to fight this Chimera. No one had told them what these men wanted. To all of them the demonstrations of this past winter were caused by trouble makers who because of their own wantonness gave good policemen much trouble and robbed them of their sleep.

The next clash between the police and the radical group occurred May 1st in Union Square, where the police again charged a helpless crowd without provocation.

It is interesting to analyze the demonstrations this winter. One is forced to the conclusion that when the police are not in evidence or are quiescent, there is neither destruction of property nor menace to life.

Again, one is inevitably driven back to the assumption that when the police beat up individuals they believe they have public opinion behind them. The editorial writers who have repeatedly urged the police to violence–the unemployed call this form of editorial “inciting to riot”–must also have believed they had public opinion back of them. The editorials in a big newspaper do not only lead public opinion, but they reflect it as well. One may with justice make a criticism of the police and of the editors of these papers that their acts and words were not those of intelligent men.

When great numbers of men meet again and again in public halls to protest against economic wrongs, or against war, or to show their sympathy with distant strikers who have been subjected to the utmost acts of brutality and disorder, the use of the club, or the advocacy of the use of the club seems an inadequate answer for the root of the disturbance. Great numbers of people do not thus gather together for no reason, especially when they do so with the knowledge that they may be ridden down or arrested. Nor do young men like O’Carroll and others of their friends–young men in the best moments of youth–young men of education, many of them with professions, sacrifice themselves and their time and energy for no reason.

There are many people in New York beside my friend the policeman who have looked upon this winter’s demonstrations as something that wantonly disturbed their peace, and like him they were “sore.” Being sore, they exaggerated the magnitude of the disturbance and did not seek the real source, any more than the policeman did.

There has even been an element of grim humor in the storm of disapproval aroused by the trespassing of hungry men on “private property”–the church of Christ–contrasted with the matter of fact way the comfortable public regards the bitter fact that in this modern city there are hundreds and hundreds of men who have no place to lay their heads. We can face the fact with complacency that in this highly organized and delicately adjusted civilization of ours there are no competent means by which jobless men and work may be joined together, and when society is made to give the matter some attention, society, as expressed by police and press, loses its temper.

The police disturbances this winter demonstrate again that you cannot keep a law without the consent of the public opinion of the State in which that law is enacted. And until the same storm of indignation arises over each act of violence on the part of the police, as that which arose over the maltreatment of the supporters of Mr. Bouck White, the police will continue to be disorderly.

Delight in suffering is rare. The cruelty born of callousness and lack of understanding is common.

The uniformed mine guards and strikebreakers who burned the Ludlow tent colony had that sort of cruelty. So have the men who open their morning papers and read with approval or even without protest editorials calling for longer nightsticks to be used for dispersing disquieting demonstrations like those of the past winter.

Trinidad and New York are not so far apart in sentiment. Indirectly, we are each one responsible for that uncivilized condition which makes possible uncivilized acts, such as the police were guilty of last winter in New York City. And while our great newspapers preach longer nightsticks, to be used on people who are indulging their constitutional right to assemble, we may be sure we have in our midst the germs of the same condition of disorder and oppression, the same callousness toward the needs of the oppressed, and the same disregard of their rights, that made possible the burning of the Ludlow tent colony.

Note.

1. This is the same Caron who was killed in the great dynamite explosion later in New York. He was known to have opposed violence before the events related here.-Editorial Note.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1914/v2n09-sep-1914.pdf