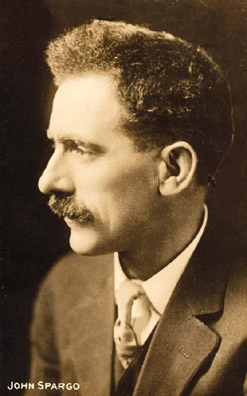

Louis C. Fraina analyzes the American Alliance for Labor and Democracy, formed in 1917 by Samuel Gompers and the A.F.L. to support the U.S. war effort, and excoriates the renegade Socialists, like John Spagro, who supported the project.

‘Labor and Democracy’ by Louis C. Fraina from Class Struggle. Vol. 1 No. 3. October, 1917.

The deeds of the government have made an unanswerable answer to the words of the convention of the American Alliance for Labor and Democracy. The Alliance appealed to the government to allow the People’s Council to hold their convention, but the government refused. While the “loyal” laborites and “socialists” were patriotically resoluting about democracy, the government instituted a series of dastardly raids against the I.W.W. and upon the national office of the Socialist Party. These reactionary acts were emphasized by President Wilson’s reply to the Pope’s message on peace — a reply that is magnificent in its rhetoric and subterfuges, but which directly promotes a brutal imperialistic war to the finish.

These incidents indicate the yawning gulf that lies between words and deeds. There is, moreover, a grim humor in the statement of John Spargo, in the New York Evening Post of September 10, in which Spargo, after pointing out the absurdity of certain charges made against the I.W.W., concluded:

“The stupidity of the policy of repression and suppression is making it increasingly difficult for radicals to support the government in its conduct of the war.”

Loyalty was dominant and hysteria rampant at this convention of the American Alliance for Labor and Democracy. The “Red, White and Blue” special was symbolic of the delegates, who in one breath prated of “internationalism,” while in the next they slobbered over the flag in approved jingoistic style. Rose Pastor Stokes, in a fit of maudlin sentimentalism, concluded an address by saying that formerly she would not salute the stars and stripes, and read an ode to America, excellent as to its patriotism, perhaps, but perfectly atrocious as a poem. Once a sentimental poseur, always one. A newspaper correspondent aptly, if unwittingly, characterized the convention in saying that it was trying to produce a “star-spangled-banner brand of Socialism and unionism intermingled.” And to cap the climax of absurdity, a resolution demanding for small nationalities “the right to live their own lives on their own soil and to develop their own culture” concluded with a declaration in favor of a Zionist state — “the reestablishment of a national homeland in Palestine on a basis of ‘self-government.” The general resolutions of the convention were obviously framed with the intention of getting support from any and all groups, irrespective of whether the things resoluted about were attainable or in conformity with a central principle of social action.

But maudlin jingoism was not the only sentiment of the convention. There was a good dash of hypocrisy. Imagine J.P. Holland, president of the New York Federation of Labor, at a convention for “labor and democracy”! It was the patriotic and democratic Mr. Holland who some months ago was responsible for the Federation passing a resolution asking the state government to suspend the labor laws, including the child labor laws, as a measure of war. This was a demand disgusting in its cruelty. It would have meant destroying the meagre safe-guards placed around the unorganized and the unskilled. Secure in their own strength and reeking with smug complacency, Holland and his cohorts were willing to offer up the children and the unorganized workers as a sacrifice on the altar of their country. Labor and democracy! And the hypocrisy was emphasized by a “manifesto” in which the renegade Socialists claimed to be “working hand in hand” with Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg!

In point of delegates and convictions, the convention physically and spiritually was dominated by the American Federation of Labor, a domination emphasized by the selection of Samuel Gompers as president of the Alliance. The reactionary character of the deliberations was an expression and an affirmation of the general attitude of the A.F. of L., an attitude that has made the A.F. of L. the bulwark of reaction in this country.

The Socialist Party, having in the past refused to take an uncompromising attitude against the principles and practice of the A.F. of L., is now reaping what it has sown. It is a matter of incontrovertible fact that the Socialist representatives in the councils of the A.F. of L. have, as a rule, assisted in strengthening the control of reaction. And that the A.F. of L. is the centre of reaction in this country is indisputable. Its narrow craft-and-caste interests exclude any large consideration of proletarian policy. It refuses to organize the bulk of the workers, limiting its activity to protecting the interests and jobs of an aristocracy of labor. It is seeking to secure a place in the governing system of the nation, to rise to power and caste privilege upon the neglect and betrayal of the great mass of the workers, the unorganized and the unskilled. In short, the A.F. of L. has pursued a policy inimical to the totality of proletarian interests and strengthened capitalist reaction, but instead of declaring war upon this reactionary attitude, the Socialist Party concluded a humiliating peace with the reactionary and generally corrupt representatives of the A.F. of L.

The policy being reactionary during peace, a similar policy during war became a matter of course.

The worst feature of the situation is that the A.F. of L. is using the war and the American Alliance for Labor and Democracy to strengthen its position, not as against the government and capitalism, but as against its radical union competitors. The A.F. of L. has surrendered to the government. It has not secured the recognition as a governmental factor that it aimed for and which the British unions have achieved. But having failed in one direction, the A.F. of L. seeks compensation in another. Accordingly, it is using the war to wage a bitter fight for the destruction of the I.W.W. and of the radical and secession unions represented in the Workmen’s Council. The American Alliance Convention did not issue a single murmur of protest at the brutal, worse-than-Prussian assaults made by the government and its representatives upon the I.W.W. Nay, on the floor of the convention of the Alliance a shameful street-gutter attack was made upon the I.W.W. and William D. Haywood by John P. Holland and cheered by the delegates — among whom, incidentally, was a bishop of the Roman Catholic Church.

The renegade Socialists at the convention, among whom were formerly bitter critics of the A.F. of L., acquiesced in every single reactionary action. The disgusting level to which these renegades stooped may be seen in the pledge which they and every other delegate had to sign:

“The undersigned hereby affirm that it is the duty of all the people of the United States, without regard to class, nationality, politics or religion, faithfully and loyally to support the government of the United States in carrying on the present war for justice, freedom and democracy to a triumphant conclusion, and gives this pledge to uphold every honorable effort for the accomplishment of that purpose, and to support the American Federation of Labor, as well as the declaration of organized labor’s representatives, made March 12, 1917, at Washington, D.C., as to ‘labor’s position in peace or in war,’ and agrees that this pledge shall be his right to membership in this conference of the American Alliance for Labor and Democracy.”

It is a disgusting pledge. Moreover, it is a complete abandonment of Socialism. It abandons the class struggle. It abandons an independent policy. It abandons the international concept. It is an acceptance of the reactionary A.F. of L. as the mentor of Socialist activity during the war.

The single radical action of the convention was its demand for the conscription of wealth. But that in itself is not an independent policy. The demand is being made strongly in Middle Class and even in Imperialistic circles. Moreover, the conscription of wealth is itself a necessity of a definite, organized Imperialism. As a measure of war it has already been introduced in Great Britain. The conscription of wealth is a plank in the platform of the new liberal Imperialism and State Socialism. In their apparently radical demand, accordingly, as well as in their general attitude and deeds, the American Alliance for Labor and Democracy is taking its place as a factor in the new social alignment precipitated by Imperialism — an alignment that distributes the burdens as well as the profits of Imperialism among privileged classes, including the aristocracy of labor.

And it is precisely in this that the American Alliance is significant in the larger sense. It is a preliminary step in the formation of a national social reform movement, which, representing the interests of the new Middle Class and the aristocracy of labor, is willing to barter away democracy and independent revolutionary action in return for concessions of social reform from a “liberal” Imperialistic bourgeoisie. This has been the policy of German Socialism, and to a lesser extent of European Socialism generally. An imperialistic social reform party — that is what will surely, in one shape or another, become a reality in the days after the war.

There are many forces working for the consummation of such a party. Certain elements of the Socialist Party, their attitude on the war aside, are fitter elements for a program of national social reform than for Socialism. That, indeed, has been the program of our party bureaucracy, which, prior to the war, was dominated jointly by John Spargo and Morris Hillquit.

The People’s Council, moreover, is equally making recruits for such a party of national social reform. The rancors of war don’t last forever, and the elements in the two camps now opposed to each other may agree to get together during the days of peace. For the People’s Council has unquestionably proven its bourgeois, nationalistic character. Their attitude during the week when they were trying to hold a convention, their craven refusal to go straight to Minneapolis, permission or no permission; their general social policies and peace terms — all these circumstances indicate their character as nationalists and social reformers. Their pacifism is a very sorry thing, and based largely upon the impulse of the moment. The People’s Council’s praise of President Wilson’s reply to the Pope’s message on peace is indicative of their bourgeois psychology.

The Socialist Party in its support of the People’s Council has again made a tactical error of the first importance. Indeed, the tragedy of the situation is seen in the circumstance that our party has practically lost its identity nationally as a force against the war. All its anti-war activity is virtually centred in the People’s Council, an organization that does not accept revolutionary action, and the conservatism of which, moreover, is strengthened by the party bureaucrats dominant in its management.

The People’s Council is being used by the Socialist Party officials to make votes for the party. This may succeed, temporarily, but its ultimate effect will be to make recruits for the Gompers-Spargo party of “practical” social reform.

Our struggle against war is simply an expression of our general struggle against Capitalism. Our action during war must square with our action and purposes during peace. And it is, therefore, mandatory upon us to scrutinize closely all movements against the war, and our own deeds. In our action against the war we should create reserves for action during peace. The People’s Council does not square with our general revolutionary aims, nor does it even adopt temporarily radical action against the war. The party should immediately separate itself from this bourgeois concern.

It is easy to sneer at the American Alliance for Labor and Democracy. It is easy to enthusiastically accept the People’s Council. The more difficult task, indispensable, is to cleave to fundamentals and express our own independent action in our own revolutionary way as adherents of international Socialism.

The Class Struggle and The Socialist Publication Society produced some of the earliest US versions of the revolutionary texts of First World War and the upheavals that followed. A project of Louis Fraina’s, the Society also published The Class Struggle. The Class Struggle is considered the first pro-Bolshevik journal in the United States and began in the aftermath of Russia’s February Revolution. A bi-monthly published between May 1917 and November 1919 in New York City by the Socialist Publication Society, its original editors were Ludwig Lore, Louis B. Boudin, and Louis C. Fraina. The Class Struggle became the primary English-language paper of the Socialist Party’s left wing and emerging Communist movement. Its last issue was published by the Communist Labor Party of America. ‘In the two years of its existence thus far, this magazine has presented the best interpretations of world events from the pens of American and Foreign Socialists. Among those who have contributed articles to its pages are: Nikolai Lenin, Leon Trotzky, Franz Mehring, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Lunacharsky, Bukharin, Hoglund, Karl Island, Friedrich Adler, and many others. The pages of this magazine will continue to print only the best and most class-conscious socialist material, and should be read by all who wish to be in contact with the living thought of the most uncompromising section of the Socialist Party.’

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/class-struggle/v1n3sep-oct1917.pdf