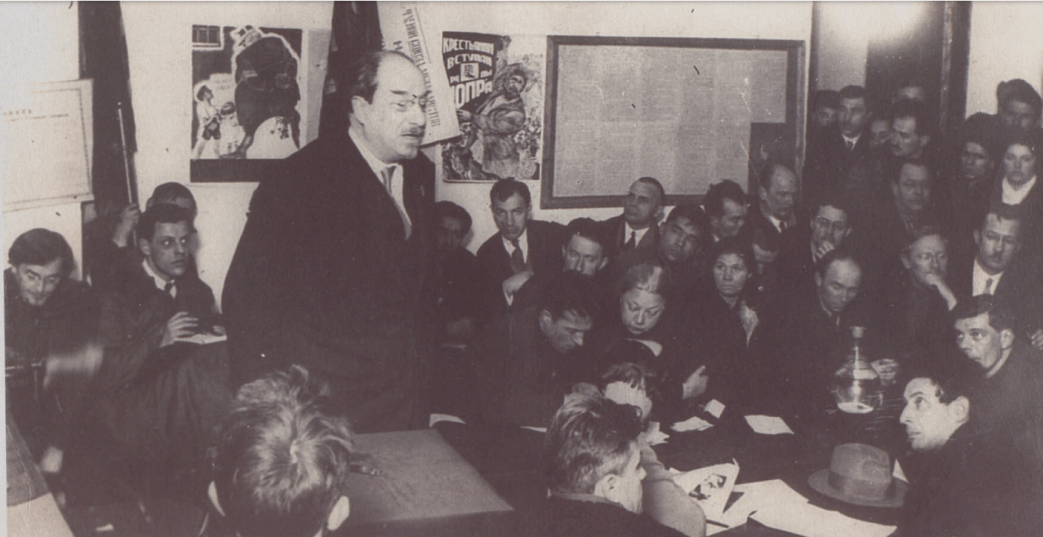

Along with immense challenges, wide horizons are presented by Commissar of Education Lunacharsky as new ways of learning were undertaken by the new Soviet system.

‘Problems of Vocational and Technical Education in Russia’ by Anatole Lunacharsky from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 2 No. 10. March 6, 1920.

Aside from being teachers, upholders of this or that ideal of education, we are first of all revolutionists, placed by the workers and peasants at the head of the liberated Russia.

The will of the working masses is clear. The people have taken the power into their hands. The sources of wealth have been seized from the clutches of grasping Capitalism in order to build up as rapidly and solidly as possible, a new national economy, uniform, regulated, and based upon scientific principles. This must be developed from the technical point of view, to form a background for the vast international policy of the proletariat, and to serve as a basis for the ultimate enjoyment of life, in the interests of Humanity.

Above everything, we are all builders of Socialism. The creation of the Socialist order is an economic problem. Politics clears the way for this construction; it unites popular will within, and protects it from outside attacks; but the real heart of the revolution is the economic transformation.

The most gigantic economic transformation that the world has ever known, can be carried out only by informed and competent people.

Inheriting our most needed resources from a somewhat feeble capitalist equipment, we must now, in spite of difficult conditions, and present disorder, turn our energies to protecting this heritage from ultimate destruction, and to increasing its productivity, bringing together all branches of this economy, which has hitherto been unorganized.

Who shall undertake this task? There is an enormous demand for able and enlightened minds, for minds equipped with the finest economic and technical knowledge that Humanity possesses. Such minds must be set to work on this great problem.

Russia is now unable to fill this demand. The number of our engineers is altogether insufficient, and moreover, they cannot all be depended upon. The number of people with a fair technical education is discouragingly small. There is an equal lack of specialized workers. The general level of technical knowledge in Russia is low. In this direction, as in many others, we are deplorably behind the rest of Europe, owing to the miserable regime which we endured for so long. Nevertheless, we have conquered, and we are ahead of all Europe on the road leading to Socialism, and also in the sense that we are actually facing the problem of Socialist construction.

What conclusion is to be drawn from this state of things? It is simply that we must study, and turn all our energies to studying. We know that a general conception of the world gives a man, not only self-assurance, but peace of mind. We know that without a broad and general culture, a man cannot discover himself. He cannot exist as a citizen, as a revolutionist, as a Socialist, without definite ideas on the world, on the history of Humanity, on the place he occupies in time and space, and on the obligations which this place in the world imposes upon him. And, needless to say, we shall never neglect this general education.

We cannot afford to have any science ignored in Russia, for all sciences are, after all, peculiarly connected, and constitute not only a superior intellectual enjoyment, but also the solid foundation on which Man builds his domination over the elements.

But not a moment must be lost in carrying out the duty which is plainly most urgent.

Is it possible that for a Socialist the study of art of systematically killing men, can have the slightest sense? And yet, forced to defend ourselves against the old world, we must accord to military instruction one of the first places. This fact is evidently the curse of our epoch. Full of respectful admiration for the revolutionary sword, which brilliantly performed its duty at the right hour, by cutting away the diseased parts from the healthy body of working Humanity, at the same time we ardently hope for the time when swords shall really be replaced by sickles.

But it is different with economic and technical education. Circumstances demand that we use at the present time all means that can be devoted to the cause of education, in order to supply the country with the greatest possible number of competent technicians in all lines.

Now remarkable attention, and love of work and of constructive action, are not a passing phenomenon; they remain eternally as the principal duty of Humanity.

The Commissariat of Public Education has succeeded in uniting all educational institutions in Russia under its direction, in order that the broadening of instruction can be carried out everywhere on the same principles. Certain technicians and economists have expressed the fear that we teachers would neglect the study of vocational and special subjects, in other words, that we would sacrifice the vocational side for the human and general side of instruction.

At the Congress of the representatives of the technical high schools, the Commissariat of Public Education was able to show how little foundation there was for such apprehensions.

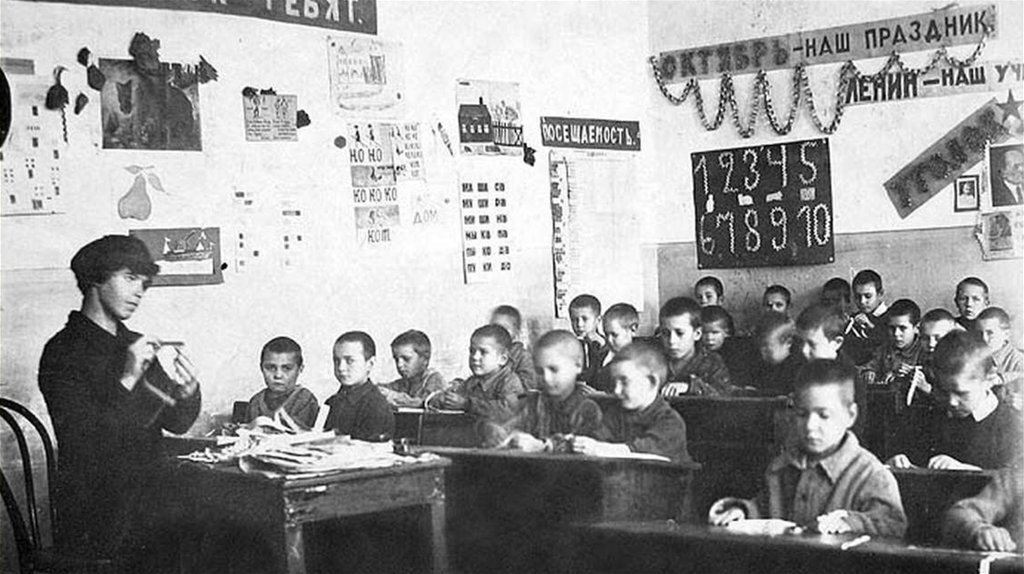

It declared that the Communist party, which is now in power, understood clearly the predominant position that economic problems occupied in life, and that the Commissariat of Public Education had not the slightest intention of destroying the technical schools, and of replacing them by institutions of the “humanitarian” type, but on the contrary, they planned to transform all schools, primary and secondary, into technical schools; thus actually increasing the number of technical schools. But the problem of the technical education of all the children and young people of Russia, that is to say, training them for work, we have treated in terms of their political instruction.

According to the declaration of the official commission relative to the purely technical school, scientific instruction in general, as well as instruction in preparation for work, which is closely connected with it, cannot be exclusive and specialized.

To specialize to such an extent would be to alter all the principles of Socialism, which preserves individuality and aims to create a highly developed type of man. It would be to condemn children in the interests of the State to bear upon their young foreheads the scar of “specialization” without taking into consideration their natural tendencies, which would inevitably show themselves later. The effect would never wear off, and would ultimately become the curse of their lives. When the bourgeois class treated the mass of workers and peasants like cattle, it could mark out their children, determining in advance whether they were to be shoe-makers, locksmiths, or hairdressers, according to its needs. But it is up to us to give to the child and to the growing boy or girl, the sort of an education that will open all doors for him later on.

This does not mean that we are hostile to specialists. On the contrary, we, too, are guided by the high ideal of a people divided according to their special callings. We believe in a state constructed like an organism, in which each cell functions independently, quite apart from other cells in the same body. But we reject most decidedly the idea of a dilettante nation, where everyone would know a little of everything, knowing nothing thoroughly, and incapable of doing anything in a talented way.

Specialization ought to begin when the child reaches seventeen years of age, which, in our opinion, is soon enough. After a prolonged period of general and polytechnical instruction, his specialization in a particular branch will not isolate him from other specialists and corporations, and nothing human will ever be unfamiliar to him.

While we are postponing technical education until the age of seventeen, we are planning to greatly enlarge instruction in this direction. There is an immediate need for a well constructed program for such instruction, a program which ought to be closely allied to some of the older secondary and high schools devoted to vocational and technical work.

There is no time to be lost. We must place our hopes in a relatively short course, carried out along military lines, to raise the general level of the technical knowledge and competence of the people. This is why we must provide an ever-increasing reserve of non-academic courses, in addition to utilizing many of the high schools, and transforming many of the secondary schools into specialized schools.

Hence, we cannot admit that the schools and narrowly specialized courses organized by isolated departments can prove sufficient. In the first place, desire for technical knowledge and for the development of natural tendencies is very strong even among the moderately class-conscious workers. And our extra-academic equipment ought to take advantage of this fact from the practical view-point, in order to connect scientific and political education with technical education, and thus bring our program in touch with the masses themselves.

In the second place, narrowly specialized schools for young and old, which are unquestionably important, will gain greatly by being organized more broadly and scientifically, and will gradually give way to the type of school that is constructed on a firmer basis of extra-academic instruction.

But let us go back to children before the age of seventeen. We have already said that we aim to establish for them a special type of school, in which polytechnical instruction is to be the chief feature in the whole curriculum. We need not go into details concerning the nature of polytechnical education, for everything of importance on this subject has already been discussed in the “Declaration concerning the School of Applied Work.”

We allow a certain departure during the last two years, when the tendencies of the children begin to show themselves, and they can chose careers to their liking.

But we do not fail to realize for an instant that the task of transforming all the primary and secondary schools of Russia into schools of applied work, is tremendous and difficult, and that it would be impossible to carry out such a complicated plan in the immediate future, because of Russia’s impoverished condition, for it would call for new equipment in all the schools, bringing them in touch with the work-shops and factories—in fact, transforming them into school farms.

We shall work untiringly for this change, encouraging all schools which realize this ideal, or even partly realize it. But we can never say that the polytechnical school exists today, for its ideal is clearly understood by everyone. Nor can we say that we are already training people on a polytechnic basis to become specialists later on.

In consideration of this fact, which ought not to discourage us, but which we must bear constantly in mind, we can treat the vocational and technical schools of the past only as worn out, which ought to be replaced by schools of applied work. This is especially true of all schools known as primary trade schools.

The infernal atmosphere which they create for poor children ought to be abolished once and for all. With us, it is needless to mention it. But other questions arise that are connected with this. In many districts the peasants and workers want to send their children to professional and technical schools, so that they may study a trade or a branch of industry useful in a particular district. It is evident that where there are such schools, we are obliged to support them, and that it is our duty to build them where they do not exist.

At the same time, we must be sure that the methods used in these schools conform as nearly as possible with the plan for the school of applied work, and see that the specialized scholars there are treated from the standpoint of general education, and brought in contact with the broadest possible supervision and ideas. To ignore this transition period by imagining that this school can be created at one fell swoop, as Minerva sprung from the head of Jupiter, would do much to prejudice the people, whose demands must be listened to with full respect for their wisdom.

This is why we must be willing to have the teaching of trades made obligatory in these schools, where existing conditions demand special consideration.

We Marxists are not among those who dream of writing beautiful ideas upon the white page of life. Facing reality in the actual process of life, we bring to it gradually the ideal which develops of itself.

Among the technical schools, especially among the intermediate schools, there are several which are excellently equipped. It must be stated, however, that owing to a false conception of the school of applied work, some of the schools so valuable to us have been closed on the pretext of replacing them by trade schools.

This is a great blunder. We must make it clear that every school with a technical equipment is of value to us. That is exactly what is needed for the realization of the school of applied work. Such schools should be placed in the category of high schools, that is to say, schools opened as special schools for young people over seventeen years of age, which will be the beginnings of schools of applied work.

One must be blind not to see that to transform a classical or ordinary primary school into a school of applied work, is infinitely more difficult than to start with the most specialized type of technical school, which possesses an equipment and personnel for technical training.

Polytechnical schools will develop from such technical schools long before the radical transformation of the old schools will take place.

Such schools, then, must be carefully kept up. But too strict specialization there must be guarded against, and general instruction must be introduced, with attention to the scientific explanation of processes of work, as discussed in the Declaration of the School of Applied Work.

The branch of the Commissariat of Public Education which deals with the reform of professional and technical instruction, will have its powers enlarged, and will be aided by specialists.

Professional and technical schools of all kinds will be placed under the supervision of the Branch of Professional and Technical Instruction. This includes the secondary and high schools of agriculture, which are of the very greatest importance to us, as well as primary schools for adults and those over fourteen years of age.

This branch must keep all these schools running, and also see that they do not get into any ruts through their specialization, but develop and broaden in their contact with reality, as they approach the ideal of the school of applied work. At the same time, technicians, as well as professors in the higher schools, and practicing engineers, must take an active part in working out this plan.

(a) Gradual reform of the professional instruction in the special schools for children between 14 and 17 years of age, to be carried out in the direction of the school of applied work;

(b) Establishment of a reserve of special schools for those over 17 years, as well as a complete reorganization of extra-academic technical instruction, for the purpose of combining it with general and political instruction;

(c) Organization of talent in all technical and high schools, which have been practically deserted, at Petrograd, for example;

(d) Instruction aided by actual work (as much as is possible under a polytechnical system) in all educational institutions in Russia.

We also give most special attention to all kinds of agricultural schools.

Besides the declaration concerning these new schools, the Commissariat of Public Education has undertaken to use them to spread among the peasant class a new idea of the rights and duties of a citizen, as well as agricultural knowledge and general education, beginning with reading and writing. At the same time, its attention must be fixed on all kinds of agricultural courses which communicate a more or less complete knowledge, and also on the agricultural institutions for young people and adults. Care must be taken never to separate agricultural instruction from civic and general scientific instruction. Needless to say, the Commissariat of Education will be powerless to accomplish these tasks unaided, even if it were assured of the co-operation of many first-class specialists.

It is above all on the working class that the Commissariat of Public Education depends for support. The closest relations ought immediately to be established between the Branch of Technical and Professional Instruction of the Commissariat and the trade unions.

In the same way, everything relating to the city industrial school must be brought closely and permanently in touch with the Council of National Economy, just as everything relating to the communal and agricultural school must be brought in touch with the Commissariat of Agriculture.

In creating the Branch of Professional and Technical Instruction, the Commissariat of Public Education is uniting such instruction closely with professional associations, with the Council of National Economy, and with the Commissariat of Agriculture, and also, for certain special questions, with the Commissariats which are specially related with the subjects taken up by certain institutions. In this way, an incessant struggle is being carried on for the maintenance and development of professional instruction in Russia.

DECREE ON TECHNICAL EDUCATION

Inasmuch as an indispensable condition of the final victory of the workers’ and peasants’ revolution is the increase of the productive work of the people, and inasmuch as the most rapid and sure way of attaining such increase is by spreading among the masses vocational education, the Council of People’s Commissars decrees:

(1) In order to extend and consolidate the work of the Branch of Vocational and Technical Instruction created by the Commissariat of Public Education, the representatives of the organizations and departments most interested in the development of vocational and technical instruction are hereby asked to join the Branch in accordance with the following regulations:

(2) All vocational and technical schools and institutions hitherto associated with Commissariats other than that of Public Education, are immediately associated with this last in accordance with Decree No. 507, of June 5, 1919.

(3) The Commissariat of. Public Education is restoring the equipment and buildings of technical and vocational schools which have been temporarily taken over for the needs of the Red Army, quarantine, etc.

(4) The committees of study, and other agencies for directing vocational and technical instruction in other Commissariats and organizations are combined under the Commissariat of Public Education, and, in cases where such measures are justified, shall be allowed provisional rights connected with other Commissariats, after an understanding with the latter.

(5) All institutions and enterprises of the State are bound to lend the Commissariat of Public Education all necessary support, supplying it promptly, and free of charge, with equipment and material, as well as placing at its disposal fabrics, factories, lots of land, experiment stations, etc.

(6) The Commissariat of Public Education is responsible for the strict execution of this decree.

President of the People’s Council of Commissars, V. Ulyanov (Lenin). Chief Clerk, V. Bonca-Bruyevich.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of original issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v1v2-soviet-russia-Jan-June-1920.pdf