In one of the industrial exposes that became the specialty of Industrial Pioneer, John Gahan looks at the history of steel making and the lot steel workers the United States, bringing the story up to his present with a visit to the mills of Gary, Indiana.

‘United States Steel’ by John A. Gahan from Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 2 No. 12. April, 1925.

SAY steel to me and I do not think of what it has done for social progress, of its gifts to civilization. I think of battles. War. War where cold steel rips flesh, and white-hot fragments of bursting shells strike down the living, defile the murdered dead. War sending human heads bouncing on shell-scarred hills and plains. Booted bodiless legs hanging in the blood-red sun of dawn on splintered trees. Mass graves plowed, re-plowed, churned by whining steel. Such is one side of the mental picture. On the other, what? More battles in the prodigious industry that has sprung to towering stature like a ruthless, restless giant.

Steel and battles are synonyms to me. That may be inconsequential, impressionistic, vague, imaginative. But it is of the utmost consequence that for all the millions of robots who have, through successive generations, given their labor, their pain and blood; whose hopes have withered and despair been born out of a grimy, sweated, endless slavery in poverty’s cesspool — I say it is of the greatest importance that they, too, have felt and do feel their toil and conflict as interchangeable terms, a oneness of class warfare not separable.

We do not suppose that this was the prevision of the inventors, Kelly and Bessemer, one in Kentucky, the other in Britain, who, independently, discovered the affinity of carbon and oxygen, thereby making heat units cheap and the development of the steel industry to gigantic proportions inevitable.

They were pioneers and small capitalists, their business was not to estimate social effects, not to foresee the appalling total of misery that has been and still is the fate of steel workers. Destiny commanded that the world complete its industrial revolution and that a well-nigh omnipotent autocracy seize empire. It was not for the inventors to calculate or compass the vast arena of embattled steel slaves periodically flinging their lives and protests against the armed forces of the masters of steel. Thair business was to profit by their discovery. Kelly was less shrewd than Bessemer, and the process of making steel is named after the latter, while for a long time in the early days this country imported steel from England, wrongly thinking the Kelly-made product inferior.

Andrew Carnegie

Along with this early steel from Britain was imported a Scotch lad whose history was fated profoundly to influence the steel industry. Andrew Carnegie was a messenger boy who picked up the trade of telegraphy. By a happy stroke of audacity, which duplicated now would land the doer in jail, — dispatching independent orders — he won the patronage of Thomas A. Scott, general superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Scott made Carnegie his secretary. Those were the happy days of oil and railroad rebates, prefiguring the railroad melons and Teapot Domes of our own enlightened day. Andy made his first money in oil speculation. “He gave his note for a block of stock in one of the smaller Pennsylvania oil companies and then paid the note out of dividends received on the stock within a single year.” His superior, Scott, was an insider, tipping Carnegie off on the best stocks to buy. The young man had no intention to let his race count for nothing, hoarding what he could, and planning to rise from a subordinate position to one of command.

Essentially Parasitic It has been said of him that he was a gambler in early experiments with steel production by the Bessemer process, but, like so many of his parasitic sort, he waited until others had beaten the trail, paved the way and found the goal. It was a sure thing when Andy made his first investment in the Iron City Forge Company, in 1864, securing one-sixth of the capital stock for $8,920. Scott and others were helping him, realizing his peculiar abilities, which when analyzed mean nothing more than the wits excessively and heartlessly to rob workers. Carnegie was their investment. With this favoritism he was able to form the Keystone Bridge Company. His profits from this enterprise paid for his stock in four years. The Pennsylvania Railroad was giving him rates by which he beat smaller competitors. This canny Scot was on the way to power.//

Then he met Henry C. Frick, a young man who made a flying start in the coke manufacturing business in Western Pennsylvania. Coke with iron ore and limestone are the three great constituents in steel manufacture. It wasn’t long until Carnegie organized the firm of Carnegie, McCandless and Company. On top of this achievement he raised $700,000 to build the Edgar Thomson Works, near Pittsburgh. It should be noted that this plant was named after the Pennsylvania Railroad president at that time. Like Pharaohs and emperors, these industrial captains wanted their vainglory satisfied. Towns and factories were named after them. This was part of the game of good business — a sycophantic practice that still endures.

Acquisition of iron ore beds speedily followed. The ore was in the Lake Superior district. To bring it from that point involved transportation difficulties, and the steel masters established steamship and railroad lines. Rockefeller owned the great Mesaba Range ore fields at first, but Carnegie and his associates convinced John D. that it was a poor investment and he, more interested in oil, sold out at a moderate figure. Very soon the property was worth tens of millions to its new owners. The stroke made possible a reduction in ore prices which crushed weaker competitors. Carnegie’s crowd quickly jumped in as bankruptcy stared these latter in the face and bought them out — cheap.

Small Business Passes

The ’Eighties and ’Nineties saw a lot of this destruction of small business. Combination was the order of the era. Several examples of this are interesting. Interesting, too, appears the new plan of concentration. The American Sugar Refining Company and the American Tobacco Company were the models for others to emulate. “Instead of placing the control of acquired plants in the hands of ‘trustees,’ holding companies were formed, which acquired all or a majority of stocks in certain competing plants under one control, often by exchanging the stock of the holding company for the stock of the plant.”

In the eight years from 1890-98 the combination of tobacco manufacturers in the American Tobacco Company increased its “capital” five times over, or in money from twenty-five to one hundred and twenty-five millions. Other combines were the Amalgamated Copper Company; the American Smelting & Refining Company, with a hundred millions and 100 plants; the fifty-million-dollar American Woolen Company, taking in a large number of New England mills; the American Car and Foundry Company; the American Hide and Leather Company, consolidating over twenty large manufacturers; and the International Paper Company, capitalized at fifty millions.

That so basic a manufacture as steel could remain outside this development is unthinkable. Yet, while the Federal Steel Company was incorporated in ’98 as a holding company to acquire stock for the Illinois Steel Company, and other steel centralization progressed, Carnegie was inclined to put too much faith in his own individuality. He was one of the old-timers, and friction concerning combination into a more powerful and interlocked managerial directorate appeared. His partners, Frick and Phipps, chiefly the former, broke friendship with him on this score. Frick was always more far-seeing. He knew that independent companies, or even minority groups, were becoming obsolete in the new industrial alignment.

The Fight for Control

The prime mover for absolute unity and control was the late J. Pierpont Morgan. This banker met Judge Elbert H. Gary, a corporation lawyer, and was convinced that Gary was the man to be made president of the monopoly yet on paper. Steel mills were being bought up, and the Elgin, Joliet and Eastern Railway was taken over. It operates in the Chicago-Gary district.

While Carnegie was holding out of the new Morgan combine, a ninety-million-dollar company was ushered on the scene by the John W. Gates crowd, combining many western plants, making barbed wire, nails and wire fencing, into the American Steel and Wire Company. Carnegie wanted to retire, but Frick did not. He was progressive.

“To his mind the days of one-man power were over; great enterprise in the future would be dominated and controlled by diverse interests; and even complete industries, if they hoped to live, would of necessity become allied with others. He believed that combination must take the place of competition.”

Though Andy wanted to get out of a business he could not dominate, he angled with characteristic cunning for his own price. William H. Moore, a Chicago capitalist of great organizing ability, was empowered to post a million dollar ninety-day option on Carnegie’s share in the company bearing his name. The price was set at $157,950,000. A temporary panic prevented Moore’s group from being able to raise the balance. Carnegie said nothing, did not extend the option a single day, and he was ahead of the game one easy million. But the Scotchman thought better of his holdings by the time a second offer was made, and he raised the price to 250 millions.

In 1897 he appointed Charles Schwab president of the Carnegie Steel Company. Schwab had made good as his secretary, manager and all-around slave driver. In addition to these virtues he was a forceful speaker. Carnegie still wanted to get out, but he wanted his price. To frighten his numerous rivals into making an effort to come to terms, he said he would fight all of them on their own ground. Accordingly, he prepared to enter the tube business against Morgan’s National Tube Company, actually securing 5,000 acres at Conneaut on Lake Erie and letting contracts for building a 12-million-dollar tube plant.

Opposing Gates and his American Steel and Wire outfit he made ready in Pittsburgh to erect a large rod mill. Rockefeller had an ore fleet on the Great Lakes and Carnegie ordered a rival one to carry ore to his mills. He announced that he would have an ore-carrying railroad constructed between Lake Erie and the Pittsburgh mills. The old fellow even put surveyors at work to plan a railroad route between the mills and the Atlantic to fight the Pennsylvania Railroad. His profits in 1900 had been $40,000,000. His mills were producing one-fourth of all Bessemer steel in the country and half of the structural steel and armor plate. He was out of debt, had lower productive costs, thanks to vicious repression of his workers and the ability to grasp new inventions and methods.

World’s Largest Sale

Then Schwab was sent to persuade Morgan. They say he talked for eight hours. At last the banker industrialist agreed to buy Carnegie out. But slaves produce wealth very fast, and by this time the price had jumped enormously. Carnegie and his associates received over $447,000,000 in stocks and bonds. It was the greatest sale in the world’s history.

Carnegie satisfied, he dropped the projects just outlined and things looked all right for Morgan. All right until he found that Gates and the other industrialists of Federal Steel except Gary did not want to let Carnegie “sandbag” them, so they raised their price on the sale and J. Pierpont was up against it to finance the monopoly purchase. He called into conference George W. Perkins, E.H. Gary, Marshall Field, Norman B. Ream, H.C. Frick and H.H. Rogers. The conference agreed that the Gates and Moore interests must be brought in, and that Standard Oil was the greatest menace owing to its ore deposits and ore fleet on the Lakes. At length Gates and Moore “came in,” and Frick was commissioned to have a little talk with John D. Frick was a believer, as has been said before, in the community of interests idea. Other champions of this credo were Cassatt of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Harriman of the Northern Pacific and Hill of the Great Northern.

Rockefeller heard Frick well and agreeably, selling for eighty millions in stock, and eight and one-half millions in cash for the ore-carrying steamers.

In this manner the United States Steel Corporation was organized in 1901 with a capitalization of $1,100,000,000, and a bonded debt of more than $300,000,000. The two greatest banking groups in Wall Street were tied to the merger. Seventy per cent of the iron and steel industry passed under the control of the new corporation at once, with scores of banks, railroads and other corporate enterprises. Later the power was strengthened by assimilating the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company, which had iron ore holdings in the Virginia district.

The Gary Dream Takes Form This greatest combine in history was capable of gigantic moves, and a glance at the map presented with this article reveals the economic reasons for the greatest constructive undertaking United States Steel ever assumed. We now look to Gary. Not the man, but the city named for him.

Not quite nineteen years ago the site on which the city now stands was a swamp and sand dune waste. The new corporation made a careful survey, weighed every consideration, and decided to assemble there on the south shore of Lake Michigan the world’s largest steel plant. This and more. A city was laid out and built. A better situation could not have been chosen. William H.

Moore’s reasons for the choice are to the point. He said of the site:

“It had the added advantage of the focus supply of the corporation’s system of subsidiary mills manufacturing sheet steel, tinplate, bridge and structural iron, wire and wire products in a continuous chain of twenty plants in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Wisconsin.”

Gary is centrally located in the region whose natural resources and manufactures are indispensable to steel making. It is near the Virginia coke ovens, the Illinois coal mines, the limestone of Michigan and the iron ore of the Lakes region. Chicago is only twenty-five miles away and this metropolis uses a great amount of structural steel. Railroad shipping costs were better by reason of the hub position in the country’s industrial wheel. Ore steamers could be unloaded right into the docks on the grounds where the red furnace tongues now hungrily lick the sky.

How many thousands of travelers have been fascinated as their trains sped through the dark past the steel mills’ glare, the streaming, sulphurous light across the night’s black dome. Some of these who peer through railroad coach windows long to go nearer this magical aurora borealis of modern industry. So I dropped off a New York Central train at Gary not many days ago for the purpose of going into the steel mills.

Getting Into the Mills

It isn’t easy to get in. Guards watch at the entrances to the walled barony that strategically fronts the lake for seven miles. You are supposed to look for a pass in the office. This might be granted, and it might not. Without the pass you somehow mingle with the crowds pouring into the Broadway entrance, pass the uniformed policemen on each side, go through the time-clock sheds. In this manner I found myself safely inside the immense domain where the slaves of 43 nationalities and races — about 30,000 in number — are busily creating in sweated toil, pain, and death — for they are “bumped off” at a fearful rate — the sinews of power for the earth’s largest known combination of management and capital.

Racial Slave Compound

Race hatreds outside may go to extremes. Within the walls of Illinois Steel prejudices are cunningly permitted to act as a spur to greater productivity, but dissension threatening to interfere with it is not tolerated. There you will find the native whites and blacks from both the North and South straining themselves in interdependent tasks beside Lithuanians, Italians, Poles, Armenians, Greeks, Russians, Hungarians, Swedes and all the rest. There is welded together in social effort a racial compound upon whose bowed back marches the empire of steel to world domination.

The Greatness of Illinois Steel

Limits of space and my own lack of technical knowledge of steel making prevent me from setting down more than an impressionist view of the Gary plant. Through the vast stretches of this arena one walks hour after hour in yards and mills and past the open hearths. To east and west an endless pile of murky structures. Machine shops, electrical power plants, blast furnaces, coke ovens, and the mills — rail mills, merchant mills, axle mills; then sheet and tinplate plants, structural steel works, pumping stations, car foundries, and the concrete ore docks.

Gouging far into the land a harbor was set. Labor’s great hands rudely lifted up the lazy, easygoing Calumet river, skillfully placing it in a new bed. Half a dozen ore steamers can be accommodated simultaneously in the turning basin. These steamers ply between the Lake Superior iron mine ports, through the Sault Ste. Marie canal, and Gary. In a couple of hours they take on their 12,000-ton cargoes of iron ore in Duluth. At the Gary port I watched Hulett unloaders scoop into the holds like giant hands, picking up 15 tons at each grasp. In a few hours an ore steamer is emptied and started on the return trip for another load.

Illinois Steel is a big outfit. That’s what you keep thinking as you hike along with far-off stacks dim in the gray distance, while you never seem to find the end. It must be a dangerous place, too, you think, because there are countless red signs posted warning not to come too near; to look out. Across one of these signs a worker had scrawled this improvement on the original legend: “Keep head in, cars cut it off dam queek.” Cranes and cars operated everywhere inside the mills and yards. Cranemen direct mechanical arms that pick up and put down twelve, fifteen, twenty tons of rails, pigs, rods, or ingots. Sometimes chains are wrapped around the loads, at other points big, round, flat electric magnets do the job.

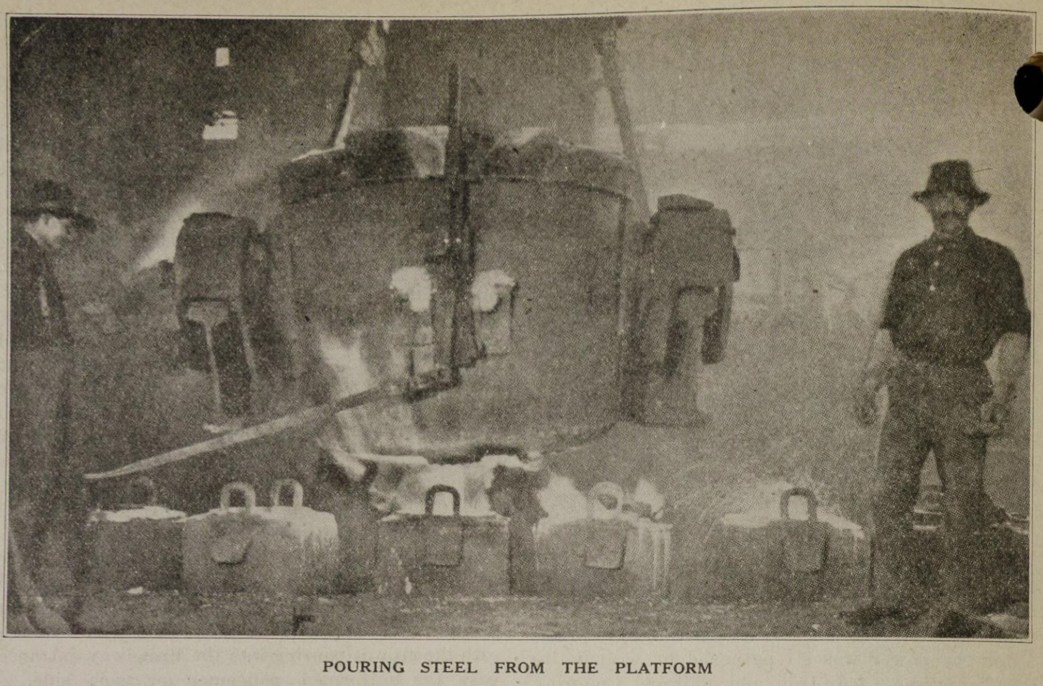

Standing back a short distance from the rail mill you see a pitch black aperture. Suddenly a white-hot snake darts out of the dark and lies still. A signal whistle toots and, with a hissing sound, the writhing snake vanishes. Going closer you see rails being drawn and straightened. At another point converters are being filled before the furnaces with liquid metal. The big jib crane runs along to this inferno, its three hooks are fastened to the great “pot” by a man, and up goes the converter.

Falling Into the Steel

Then you see the molten metal poured from these huge vessels into cylindrical containers that are loaded on special trains. When these are stripped the ingots are solid. From above carbon monoxide rises sickeningly. It is fatal to breathe it for more than fifteen minutes. A minute or two of the “gas” and you’re dizzy. In the old days, when speeding was rather a new thing, the foreign workers, unused to American industry, often found graves in the lakes of liquid steel below. When one fell in there was no need for a funeral. It was like drop of water on a red-hot flatiron, an instantaneous annihilating sizzle. This became so common that a priest protested and demanded to be given the steel to bury “in consecrated ground.”

There is an intricate system of railroading with trains, ingot-buggies, low cars for pigs, gondolas — drawn by electric and steam locomotives. Paved roads traverse the plant, and many motor trucks whiz by. In the sheet steel mill I watched hydraulic shears cut the flat metal into various lengths. In one of the merchant mills, where the noise is deafening, a white worker observed my attention as he and a negro stacked angle bars after they had been cut. Putting his mouth to my ear he shouted, “By the time the shift’s over, you can’t tell me from the other n***r.”

The Eight-Hour Day

Most of the employees are on an eight-hour basis. Some of the laborers put in ten hours. When business is very good, various departments run twelve hours, the hours over eight receiving straight-time rates. A productive basis in one of the mills — which means paying a bonus for production above a given minimum — is in force. From a few cents to a few dollars a day over the flat day-work rate can be made in most cases. But there are flagrant examples of fraud in this bonus business. One worker told me he had made seven cents a month “extra” for the last three months. The bonus can be arranged to reduce the day-work rates. In one department where the rate is $4.28 a shift they fix it like this: should even one day of the semi-monthly pay be worked on a productive (tonnage) basis, the entire pay is rated by tons and manipulated so that wages fall below the minimum.

More or less construction work progresses in the plant at all times, and I saw a small army of shovel stiffs boldly silhouetted against the northern horizon. They were filling in an immense depression near the lake. At other points gandy-dancers were fixing the tracks. My exit was made near the Y.M.C.A. Cafeteria and the Corporation Hospital. Here the wall ends, but brass buttons in the sentry box gives everyone a good “looking over.” Passing this sentinel the road drops down and curves back to town. An electric trolley runs over this thoroughfare to the tinplate mill. After a short walk a gate is passed through over which runs the legend that it is private property belonging to the Gary Land Company, and no trespassing is allowed.

Social Welfare

The homes at this end of town are clean places, the display kind, but they are depressingly monotonous in good Portland concrete. You see, the steel kings started the world’s largest cement plant at Gary’s edge, Buffington, and they boost the product. The 144 miles of sidewalk are made uniformly of concrete, too. It is at other points of this city that the low-paid slaves exist and there are five social welfare houses doing a thriving business trying to keep a lot of them from starving to death.

Gary has a fairly good library with very obliging clerks. The structure was donated by Carnegie, the land by Judge Gary, and the city meets the upkeep. In this building is collected, quite naturally, a large amount of data about the city, the mills and the history of steel. In the Gary Chamber of Commerce survey — so worded as to attract outside capital to the city — much information has been put down by these earnest Babbitts. Therefrom I learned that the mills make their own coke; that the smoke that used to go to the four winds and that settled on Monday morning clothes-lines is cleaned and used to make electricity, so that it runs the mills and supplies all electric power and lights for the city; that two trunk-line railroads were picked up over a distance of ten miles and laid out of the way to build the Illinois Steel plant; and that 90 per cent of the slaves in Gary are males, and employed in the mills. The Chamber of Commerce says that the male slaves make 44 cents an hour, the female 25 cents. It says this, too: “With the exception of the building trades, practically every establishment in Gary operates under the American plan.” Cheerio!

Then it gives the scale per hour for building workers in the city — lathers, plumbers, sheet metal workers, and structural iron workers, $1.50; plasterers, $1.37 1/2; electricians, carpenters, painters and roofers, $1.25; hod carriers one dollar, and unskilled laborers 87 1/2 cents.

Note the last element, please. Eighty-seven and one-half cents an hour for ORGANIZED unskilled laborers — 44 cents an hour for the UNorganized unskilled laborers in the steel mills. There is but one difference in the two groups — those on building construction have organized their economic power, but the mill slaves still toil without unionism for half the wage.

The Wave of Blacks

Sixteen per cent of the population of Gary is colored, or 12,700 negroes, who are but a small part of the black horde sweeping northward from the vicious sport of Southern whites — lynching. Desperately they fled. Here, then, was material to use against white steel slaves, and in 1919 they were used to break the strike. I was unable to learn how many more blacks came to Gary in the last two years, but observant workers said the number is very large. One thousand Mexicans are in the city, but other plants in the many industrial enterprises near Gary employ a larger number than Illinois Steel. With Negroes present the steel masters feel that they have a force to smash possible strikes. The black men are anxious to get settled in a new territory, and they are accustomed to a lower living standard. They are more tractable than whites, and race hatred may be engendered to cause them to fight their white fellow workers in case of strike or action leading up to a strike. This is Mr. Gary’s strategy today. The native white population in the city is only 23,400, or 30 per cent of the whole. Native whites and blacks constitute less than half of the total population, according to a census secured in December, 1924, and published for the first time in Industrial Solidarity as 78,400. With 65 churches in Gary, foreign language schools as well as the vaunted platoon brand, whites and blacks, 43 nationalities, skilled American beneficiaries in the working class getting good wages in the mills, the various employers’ associations and the K.K.K. auxiliary, a complicated situation appears when we plan- organization. Yet heroic attempts have been made by the different racial groups acting together to free themselves from their misery.

The Great Steel Strike

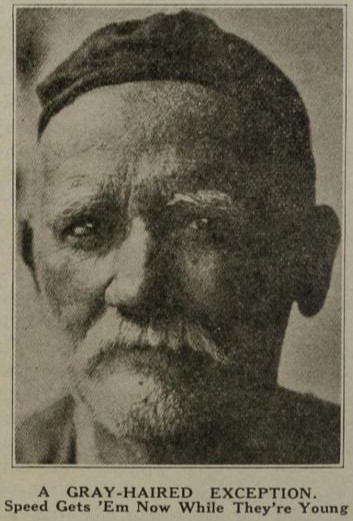

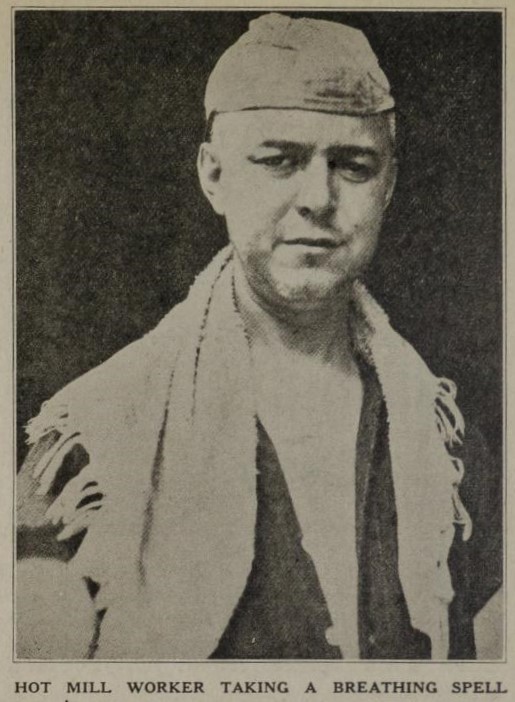

The 1919 strike was broken, but it had a far-reaching effect for improvement. United States Steel would not capitulate to a defeated rebellion, but afraid of a repetition it sought to bring about the eight-hour shifts, “gracefully,” to save its face. In Gary, at least, eight-hour weekly alternating shifts are worked by the majority. An advance has been made. But the purchasing power of wages is less now in the steel industry than it was in 1907, while the work has been speeded up to five times the rate obtaining at that time. The evil effects of this violence are most apparent in the hot metal departments. That would be the logical place to start a drive for industrial unionism.

The first demand of the 1919 conflict that involved 365,600 steel strikers was for the right to bargain collectively. That is still denied, and, of course, the other demands for a union check-off system and seniority principles were refused. The eight-hour day is not universal and is not recognized on union principle because Gary runs on the American Plan, as do all mills of the corporation. Demand Number 6 was for an “Increase in wages sufficient to guarantee American standard of living.” This is still denied the vast majority of the slaves. Number 8 called for double rates of pay for all overtime above eight hours, for holiday and Sunday work. No such rates prevail.

Need for unionism is more urgent how than it was in 1919 because the speed has been accelerated and the living standards lowered. That this organization must be on the I.W.W. plan of industrial action should be made clear to all workers. The steel barons are not organized by craft union counterparts. They have organized in One Big Union. Steel workers do not work in independent, isolated trades, but are interdependently active in the processes of industrialized manufacture. There is no other kind of unionism than the industrial form that is worth a tinker’s damn to them. No matter what the race or nation or color or sex (a small number of women are employed there) hardships and excessive exploitation are the common experiences. The I.W.W. form of organization takes all the workers of the industry into one big industrial union without regard to language, race, sex, or. creed.

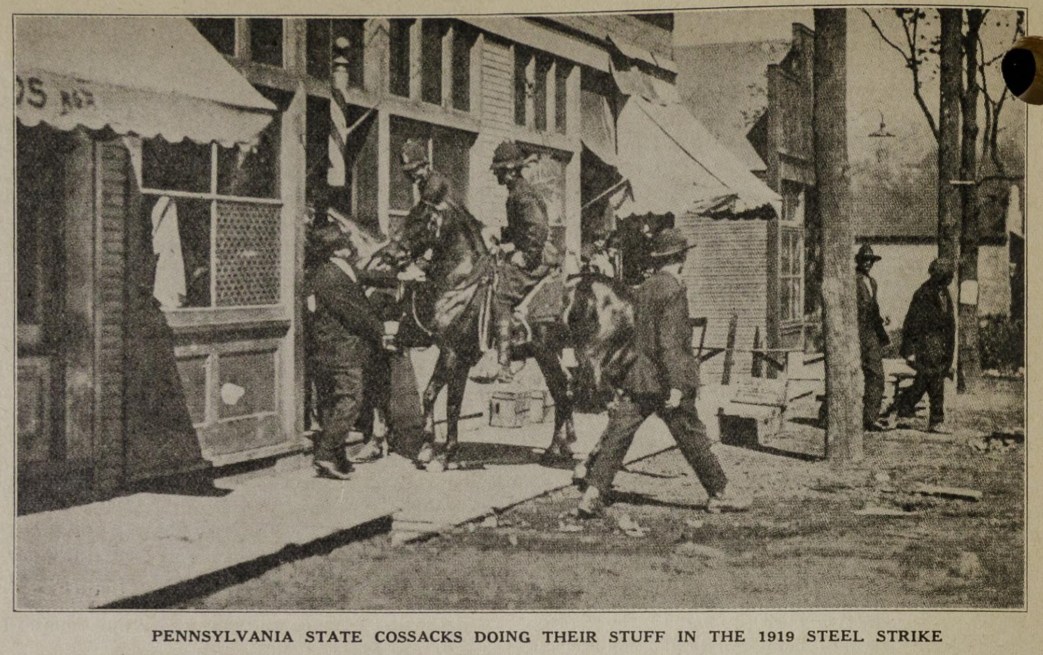

During the steel strike a certain priest, who was more of a working class rebel than he was a clergyman, said, as he fought for the strikers: “The A. F. L. doesn’t belong here. The I.W.W. should come in.” An industrial organization campaign can bring the steel workers together. In the last strike they fought bravely, suffering untold hardships, but when the hordes of pinks, stools and thugs, the militia and state cossacks, and General Wood’s regular assassins failed to beat them back to the mills, craft union officialdom’s treacherous power rallied to the masters’ need and the strike was smashed.

Fighting Homeguards

No finer spectacle of working class solidarity was ever flung across the vivid stage of class warfare than that of the steel slave hosts risen from despair’s smouldering ashes, flaming in rebellion, and holding their ranks intact from Chicago to Birmingham, Bethlehem to Pueblo. They fought against industrial autocracy. For their action they were beaten by hundreds, jailed in masses, held in high bail or without bail, and heavily fined. Twenty of them died at the hands of the steel corporation’s hirelings. But they held out. State cossacks spurred their black mounts over the “Hunky” doorsills; working class wives and mothers were outraged. Still they stood up for their convictions.

Coming from backward agricultural districts of Europe, most of these workers were not prepared to bear the exactions of modern industry. But they believed the American myth, and this faith did not die until they had been crushed to lowest depths, spat upon by their “betters.” completely enslaved. Then they rose up. The spirit of these homeguards is an inspiration to proletarian solidarity.

The long history of the steel workers is one of courageous struggle against vicious oppression. Away back in 1892 Carnegie cut wages to the bone, and the workers struck. Then he took a vacation to the Scottish lochs, leaving Frick to do the killing. An army of Pinkertons embarked at midnight on the Monongahela river, and steamed to Homestead. When they landed the strikers were waiting in battle formation to receive them. There in the early morning light, under the shadow of the hills jotted with their shacks, these steel rebels fought repression’s hirelings to a standstill, forcing them to surrender after a bloody struggle.

Time and time again has the homeguard shown that he will fight. With wife and children faced by starvation he must fight. They fought at Cabin Creek, Coeur d’Alene, on the Mesaba Range, at Lawrence and Ludlow and Herrin. Five thousand of them mobilized against industrial serfdom in West Virginia and were met with airplane and machine gun fire.

Time to Organize

A propitious moment for industrial union organization exists. Forward orders of the United States Steel Corporation published on March 11 showed for the month ending February 28 an increase over the previous month of 247,448 tons. The same report showed an unfilled tonnage of 5,284,771 tons. One year ago the orders were 371,870 tons less. Every workingman knows that the best time to attempt improvement of conditions, the period when there is the best chance for success, is when employing classes have orders ahead. There is a boom in the steel industry.

Whether we work in the steel industry or not it is our duty to upbuild our industrial unions, thereby preparing such powerful support as is requisite to any organizational campaign launched by the Industrial Workers of the World. Our opportunity to organize is great. Shall we seize it?

This was what I was wondering — just as we all wonder so often — when the western express thundered into Gary, and the leaping flames of the mills were left behind.

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

PDF of full issue (large cumulative file): https://archive.org/download/case_hd_8055_i4_r67_box_007/case_hd_8055_i4_r67_box_007.pdf