Alan Calmer reports on the rise of the movement in the ‘Border State’ of Maryland responding to national, Scottsboro, and local, Euel Lee, defense cases as well as the campaign against Jim Crow.

‘The Negro Liberation Struggle in Maryland’ by Alan Calmer from the Harlem Liberator. Vol. 1 No. 15. July 29, 1933.

“Where there is no struggle there is no progress.” – Fugitive slave from Maryland.

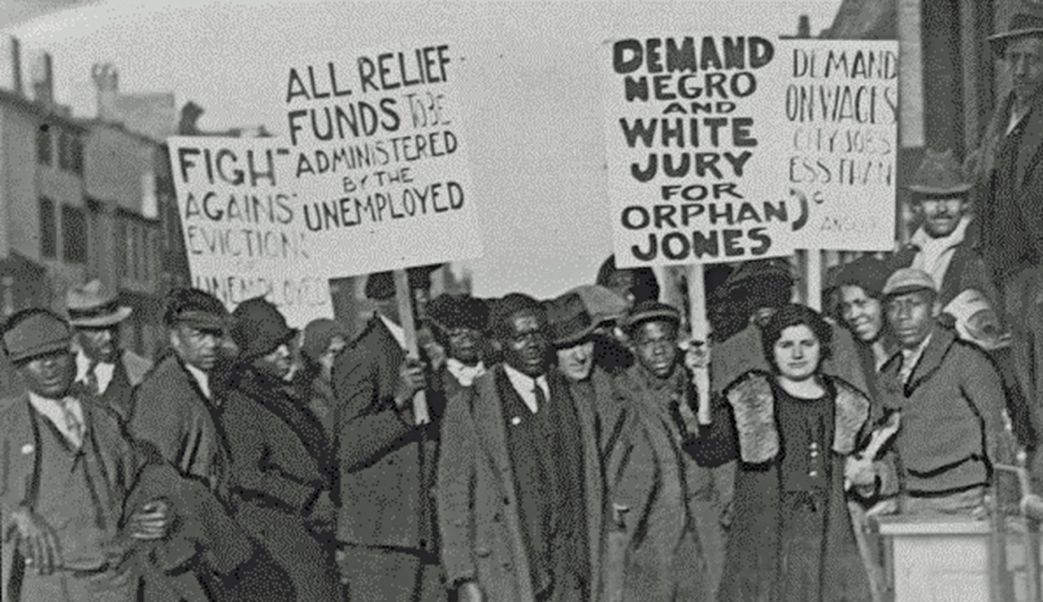

Recent episodes in the fight for Negro rights in Maryland reflect the heightening of the struggle for national liberation. The wresting of an appeal to the Supreme Court in the case of Euel Lee, the courageous attack of the International Labor Defense upon Jim-Crow laws in the “Free” State, together with the unprecedented mobilization of Baltimore Negroes for the Scottsboro March, represent the birth of a new period in the history of the Negro people of Maryland

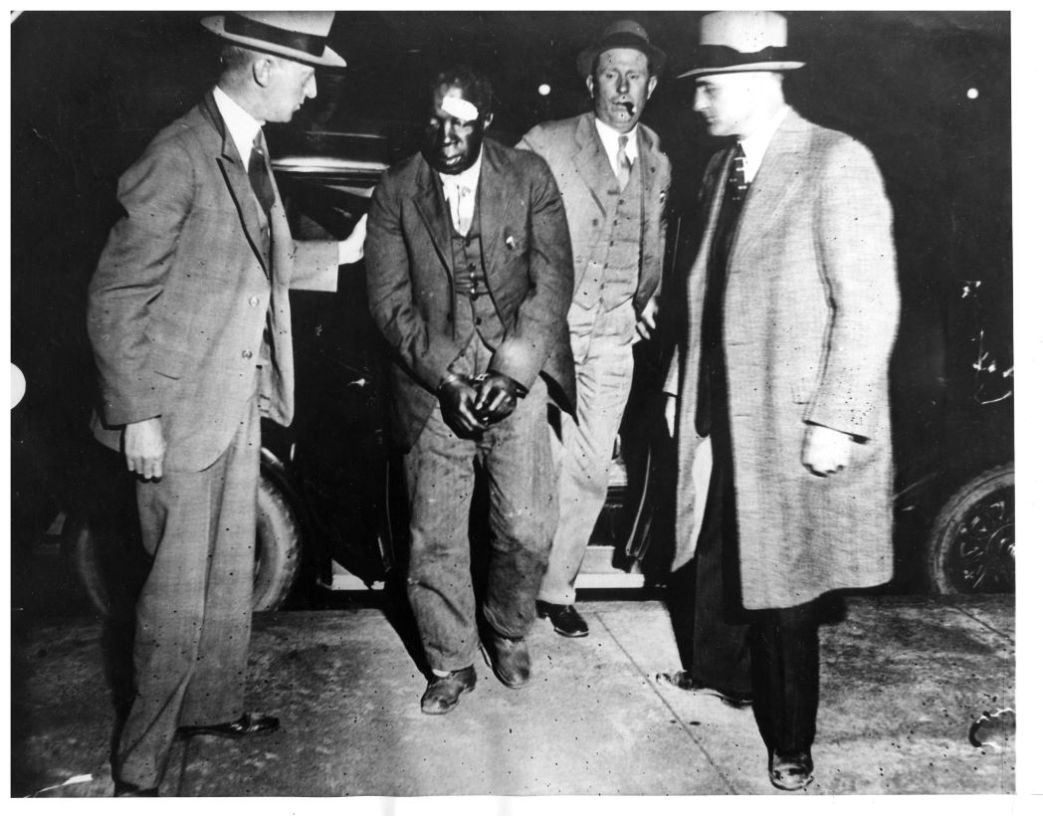

Three times the International Labor Defense has snatched the life of Euel Lee from the clutches of Maryland Jim-Crow justice. The life of this aged farm laborer framed in order to cover up malpractices of the Eastern Shore police has been saved from both illegal and legal lynchings not only through legal defense but through mass action.

Contrast of Methods

The effectiveness of this defense policy of the I.L.D. is clearly shown by contrast with a somewhat similar case that occurred in the same state in 1885. At this time a Negro, charged with the pet device of rape, was sentenced to death. He was denied an appeal on the plea of the exclusion of colored people from the jury. A group of Negro bourgeoisie in Baltimore considered the matter of testing the Jim-Crow jury law before the Supreme Court on the basis of this case. But they hesitated. Guided by reformist illusions, they did not attack the tradition of lily-white justice of the state; they assumed he was guilty and questioned the advisability of associating themselves with his name. Before their petty-bourgeois hesitancy could be resolved, the Negro was taken from the Baltimore County jail and lynched, the sixth lynching in the state in as many years during this period. Quick action by the International Labor Defense Saved Euel Lee from an Eastern Shore lynch mob, while mass demonstrations have recently won a stay of execution after Lee had been condemned to death a second time by the Maryland courts.

The “Free State” boasts of a time-honored tradition in reference to “its” Negro people, but it is the tradition of Simon Legree, Judge Lynch and Jim Crow. One of the first slave states (slavery was introduced from the adjoining state of Virginia soon after the first Negro slaves landed in America), it is popularly supposed to have been untouched by the oppression of the Southern slavocracy. Murder and butchery of Negro slaves within the borders of Maryland were, however, no rare occurrences. Volumes like the autobiography of Frederick Douglass, who fled from slavery in Talbot county on the Eastern Shore, leave no doubt regarding the “paternalism” of Maryland bourbons. As a border state in the Civil War, Maryland is popularly supposed to have been spared the reaction which followed the Reconstruction epoch in the Southern States. Yet during the same period in which. the disfranchisement of the Negro people of the South was being legalized by “grandfather”, “understanding”, and other clauses, the reactionary Maryland bosses repeatedly attempted to pass election measures against the Negroes that were more vicious than in the “solid South”. Nor must it be forgotten that the Fourteenth and the Fifteenth Amendments were both opposed by the State government.

Fight Remnants of Slavery

A determined fight against slave-code in Maryland, which still exist in the form of Jim Crow provisions, has been launched by the International Labor Defense. This campaign has been intensified in recent months. The militant spirit of a delegation led by Louis Berger (secretary of the local I.L.D.) in defying the Jim Crow regulations on the W.B. and A. Railway, and in braving the clubs of the Annapolis police to protest against the Jim Crow statute of the State, attest the determination of the Negro people, in alliance with the white workers, to wipe out Negro oppression in Maryland.

But the surging mass sentiment of Baltimore Negroes was displayed best of all during the preparations for the Scottsboro March. On the day before the army of liberation was to proceed to Washington, the Negro people rallied in large numbers to the support of their cause. A final mass meeting was planned in one of the Negro churches. The meeting place was soon overcrowded. Members of other congregations hastened to neighboring churches and persuaded their pastors to open them to swelling audiences. In addition to the scheduled meeting, five more sprung up spontaneously. This unequalled mobilization of the Negro people of Baltimore added a new page to the fighting tradition which dates back to 1776, when Negroes of the state fought valiantly in the first American bourgeois revolution. During the period of slavery, local slave insurrections were not unknown in Maryland. So ominous were the repercussions of the revolt of Nat Turner in the county of Southampton, Virginia, that the Maryland Colonization Society began the removal of free blacks to Liberia. John Brown’s raid along the borders of Western Maryland and Virginia caused even more ferment in the state. It was the famous Gorsuch case in which Negro fugitives from Maryland turned upon their bourbon pursuers and routed them which perhaps more than any other incident gave the death blow to the Fugitive Slave Law.

The unprecedented mobilization of the Baltimore Negroes for the march on Washington (in spite of an unceasing downpour, hundreds were left behind for lack of conveyances) symbolized the awakening of the Maryland Negro and forecast greater struggles are to come.

The Liberator was the paper of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights, largely edited by Benjamin Davis and begun in 1930. In 1932, its name changed to the Harlem Liberator, an again to the Negro Liberator before its run ended in 1935. The editorial board included William Patterson, James W Ford, Robert Minor, and Harry Haywood. Printed, mostly, every two weeks, The Liberator is an important record not only of radical Black politics in the early 1930s, but the ‘Harlem Renaissance’ as well. The successor to the American Negro Labor Congress, The League of Struggle for Negro Rights was organized by the Communist Party in 1930 with B.D. Amis as the LSNR’s first General Secretary, followed by Harry Haywood. Langston Hughes became its President in 1933. With the end of the Third Period and the beginning of the Popular Front, the League was closed and the CP focused on the National Negro Congress by 1935. The League supported the ‘Self-Determination for the Black Belt’ position of the Communist Party of the period and peaked at around 8000 members, with its strongest centers in Chicago and Harlem. The League was also an affiliate of the International Workers Order.

PDF of full issue: https://dds.crl.edu/item/57603