A participant in many of the events described, Ernst Meyer gives the history of struggle over the meaning of May Day between revolutionaries, like Rosa Luxemburg, and reformists within the German Social Democratic Party before World War One.

‘The 1st May and the German Socialist Party Before the War’ by Ernst Meyer from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 7 No. 25. April 20. 1927.

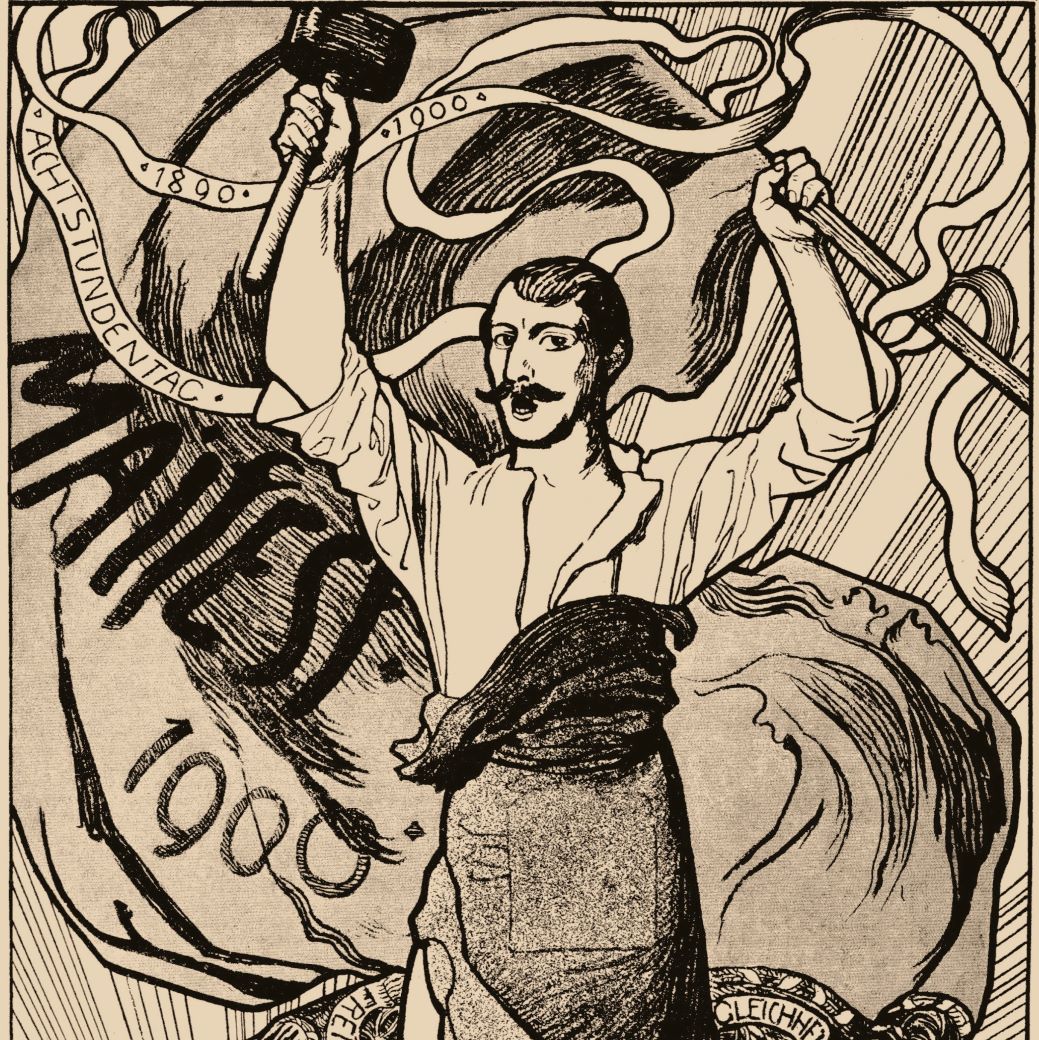

Since the time when the revolutionary socialists broke away from the social democracy, after that great betrayal by the Social Democratic Party and the II. International which culminated on 4. August 1914, our perception of those highly opportunist tendencies to which the social democrats succumbed even before the war has become much keener. It is true that the Left social democrats maintained a constant struggle against the degeneration of the revolutionary labour movement, even before the out-break of the war, but it is only now that we are in a position to realise clearly the deeper connections in the preparatory stages which led to the apostasy of August 1914. There is no question in which we cannot follow up a distinct process of preparation, dating from long before August 1914, paving the way to open transition to the camp of the bourgeoisie. The history of May day in Germany is one of the many examples of the process of adaptation on the part of social democracy to the bourgeois state of society. At the same time we may trace in this history many evidences of a growing revolutionary opposition to this line of development within the German Social Democratic Party.

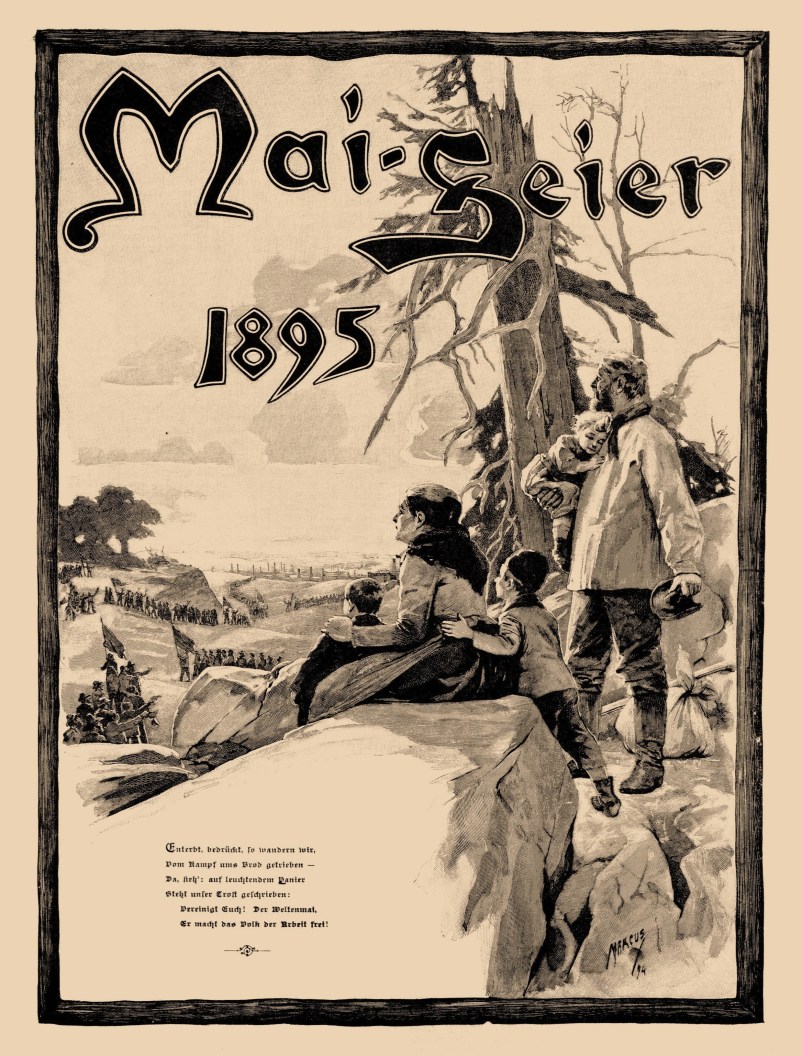

The decision of the Paris International Congress of 1899, on the May day celebration, left it to the judgment of the separate Sections of the II. International to determine the nature of the demonstration, in accordance with the conditions obtaining in each separate country. The Conference of the German Social Democratic Party held at Halle in 1890 followed the example of the Paris Congress in the following resolution, passed on 18 October:

“Should there be difficulties in the way of stopping work on this day, the processions, outdoor festivals, etc., are to be held on the first Sunday in May.”

A motion proposed by four Berlin delegates, to the effect that the May day celebration should invariably be held on the first Sunday in May, was withdrawn.

At the Berlin Party Conference in 1892 motions proposing complete stoppage of work on 1. May were rejected by 263 votes against 5. The question of whether evening celebrations should be held on 1. May, or May day celebrations on the first Sunday in May, was decided by 167 votes in favour of the first proposal, against the votes of 73 delegates who voted for the second motion.

The International Congress held at Zürich in 1893 imposed upon the social democrats of every country the duty of:

“striving for the stoppage of work on 1. May, and supporting every attempt made in this direction in different places or by the individual organisations.”

The Cologne Party Conference of the German Social Democratic Party in 1893 limited this resolution even further.

It was not until the Party Conference held at Gotha in 1896 that a decision was arrived at making it the duty of every labour organisation to stand for the general cessation of work. But this was followed immediately, at the Party Conference in Hamburg in 1897, by a motion proposed by Stolten on behalf of the delegates of the Hamburg constituency, that: “The demand for the stoppage of work on 1. May be dropped”.

However, the majority of the Party, after the withdrawal of the Hamburg motion, demanded that:

“The general cessation of work be insisted on more strongly than ever.”

At the Dresden Party Conference in 1903 a resolution proposed by the organisations of Düsseldorf and Berlin 6., in favour of complete stoppage of work on 1. May was rejected.

After the Dresden Conference the May day question formed part of the agenda of almost every party Conference. As early as the Bremen Party Conference in 1904 the speaker for the Party Committee, the then extremely radical Richard Fischer, issued a warning against any concessions to the endeavours being made by the trade union officials to abolish the stoppage of work on 1. May. He declared:

“The stronger the trade union movement becomes the greater the tendency towards a gradual loosening of the external ties binding the trade union movement to the political. And the greater the danger that the trade union movement as a whole, engaged in the every day struggles…loses sight of the great aims of the working class movement, the final goal of the emancipation of the working class from the double yoke of economic and political serfdom, the actual aim and object of the movement: the destruction of the capitalist wage system (Applause). And when our so-called good friends out of the bourgeois camp come and tell us that it is mere waste of energy…to expend money on a demonstration…that the trade unions should be economical and save their funds for the great economic struggles, then we have every reason to remember that this is nothing but the repetition of the melody of that old song of dividing the labour movement into two wings: here the wing fighting for the demands of the day, there the intransigent wing.

Weinheber, from Hamburg, openly demanded the annulment of the obligation to support the complete stoppage of work. Zubeil and Frau Zietz protested energetically against this. Fischer, in his concluding speech, again protested vigorously against the critics from the ranks of the trade unions:

“This means slipping down the path of the English trade unions, the abandonment of the class standpoint, the abandonment of the labour Standpoint, and the representation of interests which are rather considerations of the future.”

At the Cologne Trade Union Congress of 1905 the General Commission (now the General German Trade Union Federation) brought forward a resolution in which the idea of cessation of work was entirely abandoned, and Bringmann, the delegate of the carpenters’ union, even went so far as to declare:

“We must adopt a determined attitude against the decisions of the International Congress and of the Social Democratic Party Conference (which call upon us to help to accomplish a complete stoppage of work on 1. May), and declare straightforwardly and definitely that, the May day festival, in whatever form it may be celebrated, is not a form of trade union action, but that the cessation of work on the 1. May, adopted as an item of the trade union programme, is calculated to do enormous damage to the trade unions.” (!)

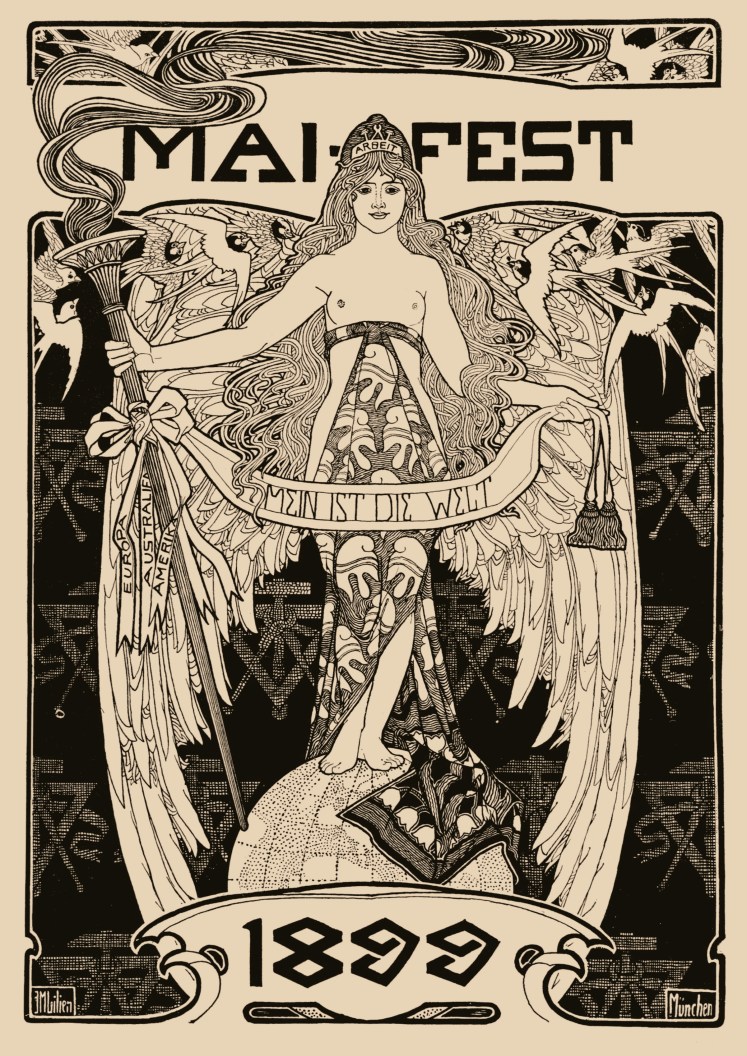

This debate was again repeated at the Jena Party Conference of the German Social Democratic Party in 1905, when Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg protested energetically against the reformist trade union ideology. The actual wording of the Jena resolution is comparatively radical. But its execution by the Party Committee, according more and more consideration to the ideas of the General Commission of the Trade Unions, fell far behind the wording. The radicals therefore opposed not only the trade union bureaucracy, but to an ever-increasing degree the Party Committee also. At later Party conferences the main point of the debate on the May day celebration was the agreements made between the Party and the trade unions, agreements in which the General Commission got more and more its own way.

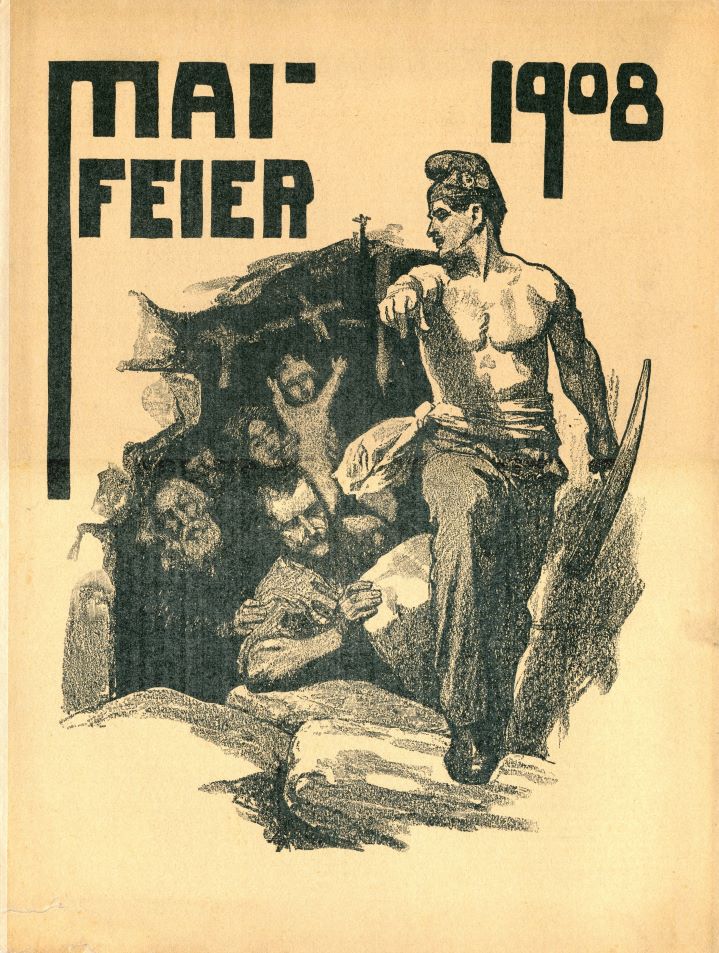

At the Party Conference at Nuremberg in 1908, Richard Fischer, once so radical, defended agreements between the Party Committee and the General Commission, in which the question of the support to be given to workers discharged for abstaining from work on 1. May was taken as an occasion for weakening the whole May day idea. Rosa Luxemburg pointed out the example given by Russia and Poland, where mighty May Day demonstrations had been held in spite of the efforts of reaction, and closed her speech with the following words:

“The sole solution to the problem is to propagate the May day idea with all possible emphasis, quite apart from this or that regulation of the support to be given to the discharged, and to cease carrying on the May day agitation in the hesitating and dragging spirit evidenced by the Party Committee and the General Commission during the past year…In Germany the May day celebration…has not only not yet shown what such a demonstration is capable of, but it has a great future before it, and in anticipation of this future it is incumbent on us to insist with the greatest determination upon energetic and unadulterated propaganda of the May day idea.”

Robert Schmidt opposed with much indignation Rosa Luxemburg’s suggestion that the Ge man workers might learn something from the Russians. His polemical tone, tinged with the “superiority” of a trade union official, was so out of place that Comrade Pieck rose and protested with refreshing candour against “the insolence of people for whom he did not feel the slightest respect”. Pieck attributed the unsatisfactory participation in the May Day celebrations mainly to the hindering tactics and resistance of the trade unions, and declared that the workers of Prussia, fighting against the three class suffrage, were prepared to make sacrifices. Lipinsky, from Leipzig, protested on formal grounds against the Party Committee for requiring that the Party Conference should merely take cognisance of the agreement come to with the General Commission, without having the right of decision, and reproached the Committee with a “cabinet policy”.

At the Nuremberg Conference no fewer than 19 motions were proposed on the May day question. The Teltow Beskow motion, proposed by Rosa Luxemburg, was as follows:

“The Party Conference sees in the May day celebration the most powerful manifestation of the class struggle, and condemns most emphatically the attempts being made in certain trade union and Party circles, to check and smother the demonstration. In order to prevent the recurrence of these attempts, so damaging to the prestige of the May day celebrations, the Party Conference expects that all such tendencies be abandoned and more consideration be given to the propagation of the cessation of work on 1. May, as decided upon at every Party Conference.

The agreements on the support given to the discharged, arrived at between the trade unions and the Party Committee, were finally altered in some points, entailing the annulment of the whole agreement.

A new agreement was submitted to the Leipzig Party Conference in 1909. It scarcely differed, however, from the agreement rejected at Nuremberg. Rosa Luxemburg was not present at this Party Conference. There was, however, a resolution from Teltow Beskow, which read as follows:

“The Party Conference declares it to be the irremissible duty of every Party comrade to engage in a far more energetic agitation for the International decision for the celebration of the 1. May by a universal cessation of work. In face of the latest attitude on the part of the trade unions, the Party Conference emphasises the impossibility of permitting any dilution of energy in the urgent and increasingly imperative measures adopted towards the ruling class in the mighty struggle for emancipation

A further motion from Elbing:

“The Party Conference resolves to oppose energetically all attempts at weakening the May day demonstration, especially its postponement to a Sunday.”

These warnings were entirely justified, for a large number of motions were brought forward in favour of withdrawing the demand for cessation of work. The Party Committee was successful in having an agreement accepted in which the form to be taken by the May day demonstration was made dependent on the approval of the trade unions.

At the Magdeburg Tarty Conference in 1919 the question of the vote for the budget in the provincial Diets occupied so much time, and the Left utilised the opportunity for such an exhaustive discussion of the necessity of a revolutionary attitude in this connection, that there was no special debate on the May day demonstration. A motion from Nuremberg: “The 1. May is to be celebrated by cessation of work only”, was rejected by 154 votes against 60. Here Karl Liebknecht succeeded in having a special division taken on this question, which the Party Committee had endeavoured to prevent.

At the Party Conference at Jena in 1911, Pfannkuch’s report was followed by another great debate on the May day celebration. A large number of organisations opened an attack on the motion passed at Nuremberg in 1908, according to which those members of the Party who suffered no loss of wages, in spite of not working on 1. May, were to contribute a day’s wages to the Party and trade union funds. Hamburg, on the other hand, demanded that all members refusing to obey the Nuremberg decision should be expelled from the Party. The Party Committee opposed both motions; its attitude was an expression of national arrogance. Pfannkuch declared:

“The German working class, organised in the German Social Democracy and German Free Trade Union movements, takes the decisions of the International Congress very seriously… According to our experience, however, this is not the case with other nations.” (!)

Ifannkuch expressed no word of appreciation for those foreign workers, the Russian workers for instance, who had demonstrated on the 1. May under the greatest difficulties, and at the cost of enormous sacrifices. Although several speakers protested with great excitement against the Hamburg motion, it was accepted by 279 votes against 101 and one abstention.

At the Party Conference at Chemnitz in 1912 a large number of motions were again submitted, having for object the cancelment of the decision that one day’s wages were to be delivered up on 1. May. One motion from Magdeburg even demanded that the International Congress in Vienna should be called upon to cancel the decision on the May day demonstration. In the course of the debate, the speaker of the Party Committee, Pfannkuch, informed the Conference that Party employees (editors) had refused to deliver up their earnings on 1. May. The same was reported by Ryssel, from Leipzig, with respect to 3 officials employed by the metal workers’ union in Dresden. A Lübeck delegate reported that a member who had been commissioned by his organisation to attend a trial of blacklegs, on 1. May, had refused to give up the day’s wages on the grounds that he had been “working.”

After a detailed debate, in which the principle involved in the May day demonstration was almost entirely ignored, the cancelment of the Nuremberg decision was accepted in open division by 270 votes against 221. After this Noske brought in a motion on behalf of the complaints commission, expressly stating that comrades obliged to work at their professions on 1. May should not be placed under the obligation to deliver up a day’s earnings. This proposal was refused.

Motions were again submitted to the Party Conference in Jena in 1913, requiring a day’s wages to be delivered up to the May day funds. The Party Committee suggested that there should be no enforced obligation, but merely the expectation expressed that the Party and trade union employees would do this. It was further proposed that the May day speakers should not be paid, but should only receive their actual expenses. Fries, Cologne, doubted whether this proposal could be carried out, since employees required as speakers would “simply strike” if not beyond paid their actual expenses.

The Left opposition abstained from expressing any definite view in this matter, since they had had the opportunity of declaring their tactical principles on the subjects of mass strikes and taxation.

This brief survey of the development of the May day demonstration in the German Social Democratic Party before the war shows the degree in which the idea of the 1. May as a fighting day fell more and more into the background among the leaders of the Social Democratic Party, and the manner in which purely financial questions were permitted to lead to deplorable debates. The Left endeavoured in vain to maintain the fighting character of the 1. May in the Party. After the initial attempts at opposition had failed, the ties binding the Party Committee to the reformist trade union bureaucracy became firmer and firmer. The Party and trade union employees finally refused quite openly, for purely material reasons, to give up a day’s earnings like the workers. And the majority at the Tarty Conferences of 1912 and 1913 sanctioned this despicable attitude by cancelling the obligation to give up a day’s earnings. The tension between the proletarian members of the Party and the Party and trade union employees became increasingly acute. The number of workers participating in the cessation of work on 1. May increased greatly during the last few years before the war.

Despite the paralysing effects of the Party and trade union bureaucracy, the elan of the masses forced its way through. Even during the war, at a time when the German Social Democratic Party and the trade unions abandoned all idea of the May day demonstration in the interests of “civil peace”, the revolutionary workers, under the leadership of the Spartacus League, organised such demonstrations as that held on 1. May 1916, when Karl Liebknecht was seized by the servants of Prussian militarism and thrown into prison.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. The ECCI also published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 monthly in German, French, Russian, and English. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1927/v07n25-apr-20-1927-inprecor-op.pdf