A valuable personal history from Heinrich Brandler up to 1908 and his emigration to Switzerland. Full of the leading figure of German Social Democracy, Brandler recounts his mentoring by Karl Liebknecht and confrontations with the revisionists as he and others attempted to build a Socialist youth movement.

‘Reminiscences of the Beginnings of the German Youth Movement’ by Heinrich Brandler from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 7 No. 50. August 25, 1927.

The first Youth organisation was founded in 1903, in Offenbach, by a Youth comrade who had immigrated from Austria and who applied the experience which he had gained in Austria in his new sphere of activity. The founding of this first organisation was purely accidental. The need of a Youth movement in Germany was acute. The German labour movement which was spreading move and move, the growth of the trade unions and co-operatives since the end of the last century, the increased membership of the Party and of the masses of voters, the transition from propaganda for socialist aims and ideas to actual practical work in the parliaments, municipalities, trade unions, and co-operatives, led inevitably to a neglect of the great world of socialist ideology, to shallowness of theory, to absorption in practical daily tasks. The catchword of revisionism: “The movement is everything, the final goal nothing”, coined at that time by Bernstein, expresses this tendency much more than we had any idea of.

Propaganda, enthusiastic and imparting enthusiasm, for the great aims of socialism, was replaced more and more by bureaucratic routine, by the trade unions and co-operatives, and the Party was guided more and more from above, instead of being built up from below, as it was at the beginning, by working masses enthusiastic for socialism. The trade unions, the young proletarian co-operatives, and the Party, were even well administered, but still they were only administered, and the initiative of the masses, the revolutionary elan, the enthusiasm and the bold offensive spirit of the movement, which had the task of shattering the capitalist world and building up the socialist, was killed off at its roots. The revolutionary German labour movement, in whose cradle Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels had laid the Communist Manifesto, and whose development they had watched over until their death, became ripe for the 4th August 1914.

The slow but steady bureaucratisation of the whole German labour movement degenerated into that disease which killed revolutionary socialism, and helped the opportunism in the Party, trade unions, and co-operatives to gain the victory for bureaucracy, in spite of the victories won, by radicalism over revisionism at all the Party conferences and international congresses. The most capable administrators became the leaders of the Party, the trade unions, and the co-operatives, not the best socialists and revolutionists. The bureaucrats of the German Party, trade unions, and co-operatives are 99 per cent of them workers, and the older ones among them, such as Scheidemann and Crispien, Paeplow and Leipart, Kasch and Fleissner, have all been really revolutionary socialist workers, true to their convictions; for only as such were they given their positions by the working masses, at the cost of great sacrifices. All of these were put in their positions in the place of vacillating petty-bourgeois.

Caught in the bureaucratic administrative apparatus, almost all have been converted from socialist Sauls to petty-bourgeois Pauls. The hydra of bureaucracy has devoured them, and they have drawn the Party and the labour movement down with them into the swamp of opportunism. It is true that certain objective causes lie at the root of the course thus taken by the German labour movement, but this does not alter the facts.

As the labour movement developed, a corresponding demand made itself felt for the furnishing of better opportunities of development for the rising generation of the German labour movement, and many efforts were made towards educational work, courses of instruction, series of lectures, and opportunities of gaining an insight into the world of ideas of scientific socialism. Here again German social democracy accomplished more, both qualitatively and quantitatively, than any other party of the II. International before the war. But the effect of these efforts was but a drop in the ocean in comparison with the bureaucratic tendencies and the sinking down into “practical daily work”. The opportunist absorption in narrow daily tasks, losing sight of the revolutionary goal, cannot be corrected by even the best training in Marxism. And it must be remembered that thorough theoretical schooling has naturally been attained by an all too small proportion of the masses, whilst practical politics involve millions, and educational work is not carried on in a vacuum, but must be adapted to the needs of practical politics.

In the discussions on the subject matter of proletarian educational work held at that time by the Party Conferences, those who stood for the setting up of the Marxist aim almost invariably won the day. But in actual practice the administrating bureaucrats exercised an influence converting the educational institutions intended for the revolutionary training of the masses into schools for good bureaucrats, well versed in the art of reeling off radical phrases calculated to render opportunist treachery palatable to the masses.

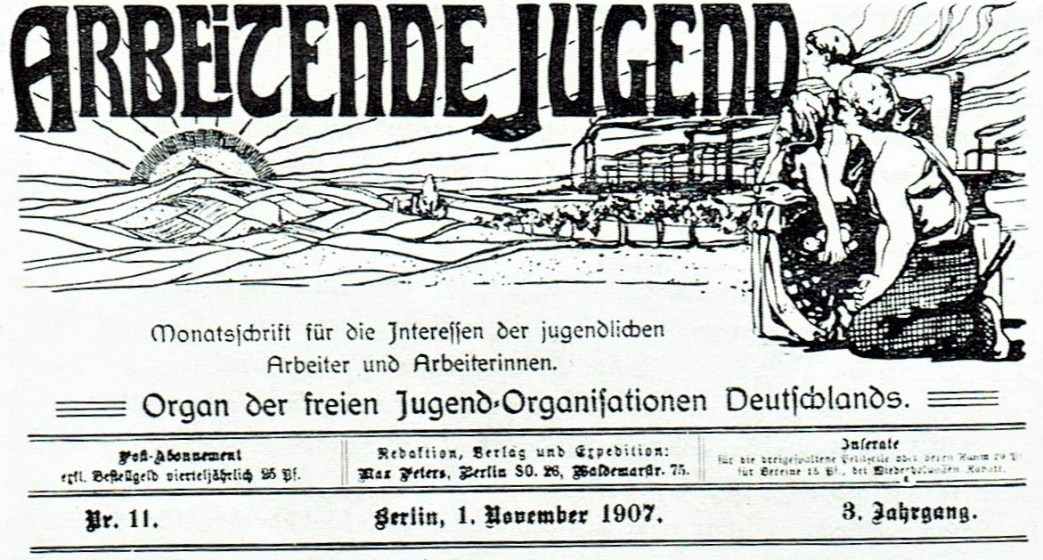

This fate was shared by the Youth movement. One of the first to propagate the idea of a proletarian Youth movement supported by the Party, but otherwise independent, was the Mannheim lawyer Ludwig Frank. At first he, too, was extremely radical. The “Junge Garde”, the organ of the South German league of the young workers of Germany, began as a Youth paper edited in a revolutionary spirit.

At the first conference of the League, held on 30th September 1906, it was resolved to establish international relations among the Youth Leagues. The result was the First International Youth Conference, held in connection with the International Socialist Congress at Stuttgart, and attended by 20 delegates representing 13 countries. This Conference, at which the report of the International Secretariat was given by the Belgian De Man, who was living at that time as a student at Leipzig, and the Dutch comrade Henriette Roland Holst spoke on “The socialist education of Youth”, the Hungarian Julius Alpari, who was also living in Germany, on “The economic struggle of the working Youth”, and Karl Liebknecht on “The fight against militarism”, gave the signal for the bureaucracy of the Party and the trade unions to take the matter into their hands.

The theses on the socialist education of the young workers set the Youth organisations exclusively educational tasks, and put “the struggle into the second place”. But they demand independent Youth organisations, which “are to maintain an organic connection with the class-conscious labour movement”. This, first of all, was impossible of acceptance by trade union bureaucracy. They protested against it at their trade union congress at Hamburg, and combated at the same time the resolution on the economic struggle of the juvenile workers, stating that this could only be the affair of the adult workers in the trade unions. In actual practice the trade unions did practically nothing for the improvement of the wages and working conditions of the young workers and apprentices.

The address given by Karl Liebknecht on the fight against militarism aroused the special indignation of the bureaucrats. Although no theses on this subject were accepted by the Conference, the bureaucrats made open protest against, such propaganda, and declared themselves to be entirely opposed to “poisoning youthful minds with class struggle propaganda”. Youth must be kept youthful, by means of games, rambles, reading from eclectic improving literature, and the like.

Ludwig Frank, who had kept aloof from the International Conference, attempted at the Darmstadt Conference, which took place at the end of 1907 or the beginning of 1908, to deliver the South German League of young workers into the hands of the general commission of the trade unions. He and Robert Schmidt of the general commission were successful in influencing the Conference. I, as delegate from Bremen, remained in a hopeless minority with the Hamburg delegates. The Bremen youth organisation, of which I was leader, then broke off relations with the Mannheim league, to which we had affiliated ourselves because its original statutes allowed more freedom for the work of political enlightenment than the Berlin league, which prohibited political work for reasons connected with the law of associations. Ludwig Frank further declined our invitation to explain his standpoint to us in Bremen, as we had “offended” him.

I may here quote from memory a few episodes out of my own experiences as living illustrations of the history of the development of the German Youth movement.

In 1901 I went to Hamburg. There I sought out the local workers’ educational association and joined it. This association was, however, at that time in the hands of educational Philistines of a semi-anarchist type, petty-bourgeois, and worker aristocrats, whose conceptions of enlightenment for the workers did not go beyond dabbling in art, visiting museums, and recitation evenings. Otto Ernst, court and household author, played a great role. It was only the extremely instructive introductory course of lectures on political economy given by Franz Laufkötter, which gave what I sought. Before this I had made a trial of the Free-thinkers, but had been revolted by the description of free religious piety preached by these people, among whom not a trace of proletarian thought was to be found. I read much, but quite indiscriminately. Works on natural science, Karl Marx, difficult philosophical works which I did not fully understand, and the classics.

After much reading, and after attending the Party Conference debates, I began to read along more definite lines. I became interested in the questions raised by the Lübeck Party Conference in the course of its debates on piece-work in the bricklaying trade, and on revisionism. I subscribed to the “Neue Zeit”, and the weekly articles by Franz Mehring, which always threw much theoretical and historical light on the most important questions of the day, were for me a guide to a thorough study of scientific socialism.

I made an attempt to form, in the continuation school society and in a special club, the “Prometheus”, a circle in which young comrades could study the practical and theoretical problems of the labour movement. But here again we did not get beyond Philistine attempts at education and art. I made up my mind to leave the continuation school society, but resolved to tell them my opinion properly first. to tell them my opinion properly first. I therefore took the opportunity offered by a general meeting of the continuation school society, at which two differing aesthetic groupings were squabbling with one another, and expressed my opinion very forcibly in plain and blunt bricklayer’s style. I fully expected to be thrown out. But quite the contrary. I got the majority of the meeting onto my side, the old committee was dismissed, I was elected chairman, and a majority of those in agreement with me formed the committee.

This went somewhat beyond my powers. I could not, however, turn back. We started to work, sought and found suitable teachers. I wrote my first leaflet, making propaganda for the reorganised continuation school society, and applied for help to the Party and the trade unions. This help was refused by the Party, but granted by the trade unions of the masons, metal workers, and wood workers. We arranged courses of instruction in the history of the present-day labour movement, national economy, and historical materialism, in addition to the courses which had been held before in book-keeping, history of literature, German, etc. This was still not a Youth organisation or Youth movement, but the history of this transformation of an old and petrified workers’ educational association into an association for the class training of young people shows how greatly the need was felt for the training of the rising generation of the labour movement.

At Christmas 1904 the Hamburg Senate acknowledged my activities for the development of proletarian class schooling by turning me out. Both in the educational association and in the meetings of the Party and the trade unions, I had supported the proposal made by Karl Liebknecht at the Bremen Party Conference for the formation of Youth organisations, and for a special anti-militarist propaganda to be carried on by the Party. He was not successful in having this proposal accepted. On the contrary, the whole Party Conference opposed him. I was, however, as much convinced of the necessity of the formation of Youth organisations, as of the necessity of anti-militarist propaganda. The sharp attacks made on me in the Party and trade unions failed to convince me that I was wrong, but apparently they convinced the Senate. After my expulsion in Hamburg I went to Bremen, where a more radical wind was beginning to blow in the Party.

The Bremen workers had begun to fight seriously against Fritz Ebert, who was a sort of uncrowned king in his capacity of labour secretary and chairman of the Bremen corporation fraction, and was guiding the Party and the trade union movement into the backwaters of revisionist opportunism.

Heinrich Schulz, a former elementary school teacher at Bremen, after working on revisionist lines in Erfurt, was called to Bremen by the press commission controlled by Ebert, in order that he might provide the “Bremer Bürgerzeitung” with revisionist theories in support of the opportunist practice of Fritz Ebert. But in Bremen Heinrich Schulz became converted from a revisionist Saul into a radical Paul. Under the influence of Alfred Henke, a former tobacco worker, the “Bremer Bürgerzeitung” gradually changed into an organ of radicalism, and developed courageously into a Left radical organ with the collaboration of Knief, whom I brought over to Youth and Party work out of the young teachers’ group, and of Pannekook and Radek, whom we called to Bremen. The “Bremer Bürgerzeitung’ still held its standpoint firmly at the time when the “Leipziger Volkszeitung” began to slip back into centrism under the influence of Lensch.

During the first years of my sojourn in Bremen the fight against Ebert’s opportunism, the fight on the questions of the mass strike, and on other tactical differences, absorbed the whole of my powers and those of my co-partners. Again we had to do with the question of education training or Philistine education and this question became one of the greatest bones of contention both in the whole Party and in Bremen. Fritz Ebert, who lost more and more ground in Bremen, was thrown upstairs instead of down. and was accorded a place in the Berlin Party Committee. We were glad to be rid of him, and continued a successful fight against his adherents: Teichmann, first chairman of the tobacco workers’ union, Winkelmann, first chairman of the coopers’ union, and a number of smaller trade union bosses.

At the end of 1905 I founded a Youth Organisation in Bremen, in which undertaking I was supported by the radical majority of the Party, but violently combatted by the revisionist trade union leaders, whose open resistance we were, however, able to break in the members’ meetings of the trade unions, at which I gave many addresses on the necessity of a Youth movement. At this time I entered into communication, by letter and personally, with Karl Liebknecht and Ludwig Frank. There are about 30 letters to me from Karl Liebknecht in existence, as also some from Frank, De Man, and Peters. I left these with the association when I left Bremen, and they can perhaps be brought to light again. They contained much that would give a detailed insight into the beginnings of the German Youth movement.

Besides the work of education based on the class standpoint, we made it our endeavour from the very beginning to support to the utmost the economic interests of the juvenile workers und apprentices. We had not, however, much practical success to record. Up in the attic of the trade union premises we were given a room for a Youth home, and this was open every evening and on Sundays. The existence of the Youth organisation was secured, the membership increased slowly but surely. But the object of the organisation, whether it was to be mere Youth welfare work or an independent Youth movement with the support of the Party and trade unions, remained the subject of violent contention up to the time at which I left Bremen, at the end of 1908.

When the trade union bureaucracy could no longer prevent the formation of a German Youth movement, it endeavoured to gain influence over it by means of participation. The culmination of the independent German Youth movement was the International Conference of 1907.

After the International Conference, the trade union and Party bureaucracy intensified their efforts to undermine the independent Youth movement. At the Hamburg Trade Union Congress the trade union bureaucrats attacked us openly. This attack led to a compromise with the Party Committee, which placed the question of the Youth organisation on the agenda of the Nuremberg Party Conference, and then utilised the commission appointed for the purpose, without any discussion at the Conference itself, for placing the independent Youth organisation completely under the domination of Party and trade union bureaucracy. Henke, Wilhelm Pieck, and I were at the Nuremberg Party Conference in 1908, as delegates from Bremen. Before the Party Conference I took part in the Youth Conference held in Leipzig in August 1908, as representative of the Bremen Youth, who had commissioned me to act as spokesman for the Youth at the Party Congress. From Leipzig I went to Glatz, where Karl Liebknecht was still imprisoned in the fortress, having received a sentence of eighteen months imprisonment for his book on “Anti-militarism”. I wished to consult with him on the way I should represent our standpoint at the Party Conference.

At the meeting of the plenum of the Party Conference I was given no opportunity of speaking on the Youth movement, for there was no discussion whatever, but I was elected to the commission. In the commission I came into violent conflict with Legien and Ebert, and was only supported by Klara Zetkin. The cause of disagreement was the ready-made compromise resolution, which had merely received a few alterations in style in a select editorial commission, and was to be submitted to the Party Conference, without discussion, as the result of the consultations of the commission.

After the Nuremberg Party Conference in the late autumn of 1908, we had another consultation in Karl Liebknecht’s lawyer’s office in Berlin. Liebknecht had contrived to obtain a fortnight’s leave of absence for the arrangement of his family affairs, and was present. We talked over the latest facts created by the Nuremberg decisions. Ebert was chairman of the national Youth Committee, Korn the editor of the new periodical published by the central committee, the “Junge Arbeiter”. The trade unions were beginning to form Youth sections. We resolved to take part in everything, and save what we could of the independence of the Youth movement and the proletarian class import of the educational work. We could not, however, prevent the backsliding into mere Youth welfare.

The old revolutionary traditions of the Youth movement were, however, never eradicated, despite all the measures taken by bureaucracy. This could be seen after the outbreak of the war, when we many of us old acquaintances from the time of these old struggles for the Youth movement met again in the Spartacus League, and then again when our revolutionary work against the war found its first supporters among the new Youth.

At the end of 1908 I left the German Youth movement, as I left Bremen to settle in Switzerland. I give you these reminiscences, in order that our young comrades under the more favourable conditions ruling today may learn how to do better than we did.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. The ECCI also published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 monthly in German, French, Russian, and English. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1927/v07n50-aug-25-1927-inprecor-op.pdf