Art critic Harold Rosenberg looks at the first major van Gogh exhibition in the United States held at the Museum of Modern Art.

‘Peasants and Pure Art’ by Harold Rosenberg from Art Front. Vol. 2 No. 2. January, 1936.

VAN GOGH is both overrated and undervalued that is to say, his reputation has by no means been placed upon a stable level. The difficulty is that his paintings affect people in an anti-critical way. Like D.H. Lawrence, he is supported by a cadre of enthusiasts whose responses to his work contain more of religious sentiment than of art-appreciation. And out of this revivalist atmosphere, and as an antithesis to it, atheist and agnostic orders of enemies have been generated those to whom the very name of van Gogh is the signal for gestures of repulsion or for a bellicose indifference.

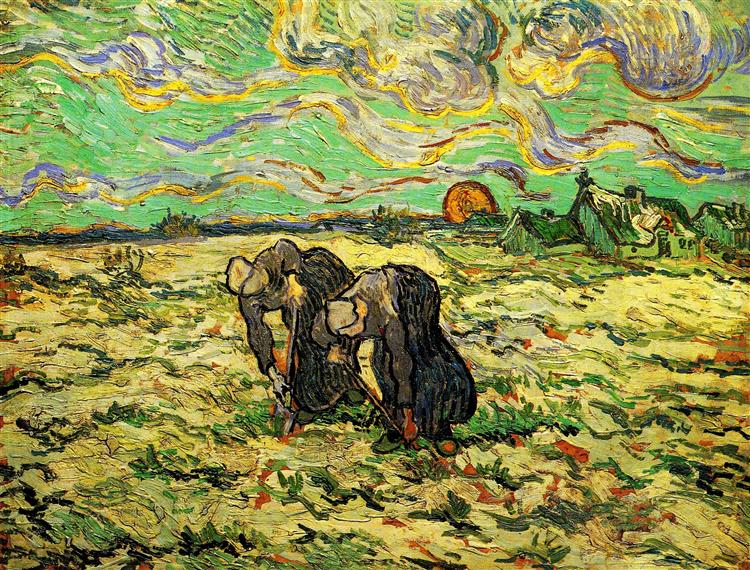

The first comprehensive exhibition of van Gogh’s paintings in America, at the Museum of Modern Art, should do a great deal toward dissolving the emotional steam that rises about the figure of the passionate Dutch colorist. For example, it is for many of us a first introduction to the “sober” paintings and drawings of his Dutch period. These scenes of peasant life and drawings of workingmen, far from falling into the interesting but mere insignificant category of “student work”, are in themselves sufficient to justify new perspectives with regard to van Gogh’s development and to imply a need to reinterpret the direction of his art in relation to his letters and social situation.

The major portion of the exhibition, devoted to the more familiar products of his later periods–a profusion of the great lights of Arles, St. Remy, and Auvers–multiply and deepen these impacts upon the sensibilities which we have been accustomed to associate with van Gogh. Upon these decorations the fame of van Gogh rests. If the mysticism of color (“I have tried to express the terrible passions of humanity by means of red and green”) and the indiscriminate violence of the manner do operate at the expense of everything in the art of painting which does not pertain to a language of personal temperament, yet these works define the artist, and it is in their qualities that the key to his position is to be found.

The structural defects of van Gogh’s masterpieces, the inconsequentiality of the composition and the lack of plastic differentiation, are, when not overlooked entirely, attributed customarily to a temperamental necessity without which his genius would be inconceivable. It is argued that the painter must be accepted whole, that his successes and failures are part of one indivisible entity the “seer” van Gogh. The fits of madness from which van Gogh suffered in the midst of his most productive years are taken to substantiate this view.

While it is impossible in a review to examine the conditions, both social and psychological, which determined van Gogh’s work, it seems to me that the Dutch paintings clearly establish that van Gogh was by no means orientated in some primitive, natural, or instinctive manner toward the dynamism and color-occultism by which he is distinguished. Rather were these qualities and these attitudes evoked from the realm of the possible and expanded to all-inclusive proportions by the pressure of external forces among which the dominant role was played by certain configurations of social events. In other words, van Gogh became the burning “expressionist” van Gogh, the van Gogh of purely inner struggles with the problems of natural magic, only after a great number of equally “characteristic” efforts had been utterly defeated.

Among these defeated efforts, which included careers as picture salesman, theology student and lay preacher, are to be reckoned the humanitarian paintings of the Dutch period, “The Weaver,” “Ox Cart”, “Potato Diggers”, “Potato Eaters’, etc. The Dutch paintings achieve distinction, but their tendency to go counter to the main current of late 19th century taste is obvious. Like van Gogh himself, these social paintings could have found no place in the society of his day–except in that area where no careers exist, in the homes of peasants and workingmen. This van Gogh divined–“as it is useful and necessary that Dutch drawings are made, printed, and spread, destined for the houses of workmen–” yet there always remained the problem of making a living: “I am always between two currents of thought, first the material difficulties, turning round and round to make a living; and second, study of color.”

To develop an art for the poor was not a task that could be accomplished by any one man. Having left the society of peasants and artisans, the problem of achieving a successful career presented itself once more. Helpless in the face of this problem, van Gogh devoted his art to the satisfaction and relief of his own ego. This so-called “escape” cast him directly in the path of Parisian modernism which, in that epoch, was engaged in the discovery and exploitation of new realms of sensation.

Van Gogh was incapable of reconciling his humanitarian devotions with the contemporaneous salon styles. No pleasant, “perfumed” paintings of manual labor. By no chance could his workmen have inherited the popularity with the upper classes which the pensive field-creatures of Breton enjoy. It was a question of painting either for peasants or painting for himself–and the latter, in his case, meant, painting for Art.

Van Gogh’s inability to compromise in this connection is associated with the most significant and enduring feature of his talents: his power of direct statement. It is this quality which ties his Dutch paintings to the main body of his work, and which brings the whole forward into our own day as an influence which, under careful control, may yet produce valuable results in art. Both in the days when his concern with social subject-matter caused him to use color as a term in an objective, accurate depiction of the quality a human condition, and later when, from an opposite point of view, color became itself the direct voice of his own suffering, the paintings of van Gogh are characterized by a declarative persuasiveness which is made possible only through the release of the imagination by means of determined vision. His peasant-paintings could not have been popular in the salons paintings because they said too many simple and unmistakable things about the lives of the people–and his flowers, portraits, and skies did become popular even outside the salons because they said so many new and unequivocal things about the sun, people’s faces, trees. It was under the auspices of history that this directness and appearance-altering simplicity came to be applied to landscape, sunflowers and the works of other artists; in our own day, van Gogh might not have found his original efforts to speak to the working people in whose society he lived so inconsistent with the movement of art.

In sum, though van Gogh converted his did so not through temperamental but art into a language of temperament, he through social causes. Temperamentally, he was moved to make painting into an instrument of solace and self-knowledge for the masses. Since this could not be achieved unaided, his painting became the means for discovering a transfiguring element in the physical appearance of a world which his experience had found intolerable.

Art Front was published by the Artists Union in New York between November 1934 and December 1937. Its roots were with the Artists Committee of Action formed to defend Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads mural soon to be destroyed by Nelson Rockefeller. Herman Baron, director of the American Contemporary Art gallery, was managing editor in collaboration with the Artists Union in a project largely politically aligned with the Communist Party USA.. An editorial committee of sixteen with eight from each group serving. Those from the Artists Committee of Action were Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Zoltan Hecht, Lionel S. Reiss, Hilda Abel, Harold Baumbach, Abraham Harriton, Rosa Pringle and Jennings Tofel, while those from the Artists Union were Boris Gorelick, Katherine Gridley, Ethel Olenikov, Robert Jonas, Kruckman, Michael Loew, C. Mactarian and Max Spivak.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/art-front/v2n02-jan-1936-Art-Front.pdf