Fellow-worker Robert Grayson looks at where he works; the history, techniques, conditions, and organization of the glass making industry.

‘The Glass Industry’ by Robert Grayson from Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 1 No. 2. March, 1921.

THE MAKING of pottery marks the transition of the human race from savagery into barbarism. Second only in importance to pottery as a cultural advance is the discovery of glass, dating much later. While the exact period of this discovery is not known, there exist proofs that mankind had made it as early as 4000 B.C., and well-preserved specimens, estimated to be about three and one half thousand years old, have been found in the ancient tombs of Thebes. These consist chiefly of beads and of small containers. It is debatable as to what race made the discovery, both Egyptians and Syrians claiming the honor; moreover, the historian Pliny relates a story concerning the origin of glass which may hold some truth. He tells of a group of Phoenician mariners who camped one evening on a river bank in Palestine. Unable to find stones on the sand upon which to rest their cooking utensils, they pressed into service some lumps of soda from their cargo. The action of the heat fused the soda and the sand, the result being a viscous mass which became transparent after cooling.

The Greeks and Romans learned the art of glass making from their neighbors on the Nile, and as early as the reign of Nero clear or crystal drinking vessels, such as tumblers, cups and goblets, came into use and found high favor among the patrician class. The history of the workers in glass is unknown. We may read where a ruler or noble prized good works in the art, but everything concerning the craftsman has been obliterated.

After the Romans, the greatest masters in the art of glass manufacture are the Venetians and Muranians. The former so revolutionized its processes as to permit of much lower cost, thereby placing the article for the first time into extensive use. Furthermore, they are credited with having introduced glass into Western Europe. Jacob Verzelina, who migrated to England about 1550, made both window-panes and table ware until his death in 1606.

At Stourbridge, England, a factory for the making of window ware was erected in 1619. The close proximity of fire-clay mines accounts for this institution. This leads us to a description of the composition of glass and the technique of its manufacture.

COMPOSITION.

Glass is a hard, brittle, viscous, non-crystalline substance, either transparent, opaque or translucent. It is the result of a fusion of silica and active mineral fluxes or solvents, including alkalies, earthy bases and oxides. Silica is found in a free natural state among flints, quartz and sand. Sometimes the first two are used by pulverizing them, but the latter is in most general use.

In this country many kinds of glass are made. Potash, lime, and soda are important ingredients. The war closed the commerce with Germany, where a practical monopoly of potash obtains, and as this is the most purifying element in the composition of glass ware the product has been since 1914 of an inferior grade so far as crystal ware is concerned. Varmus chemicals are fused with the silica and alkalies to effect coloring.

TECHNIQUE.

It is said that ancient glass makers worked the molten mass around a core of sand, which was afterward removed. But eventually it dawned upon them that the use of a pipe with a hollow stem would permit the blowing of the glass. We will now treat of this phase of the industry; in passing we will remark that the container for the molten glass is a clay pot capable of resisting enormous heat, and that a glass factory furnace is usually a cylindrical form of brick with a number of apertures communicating with the various pots of molten glass within.

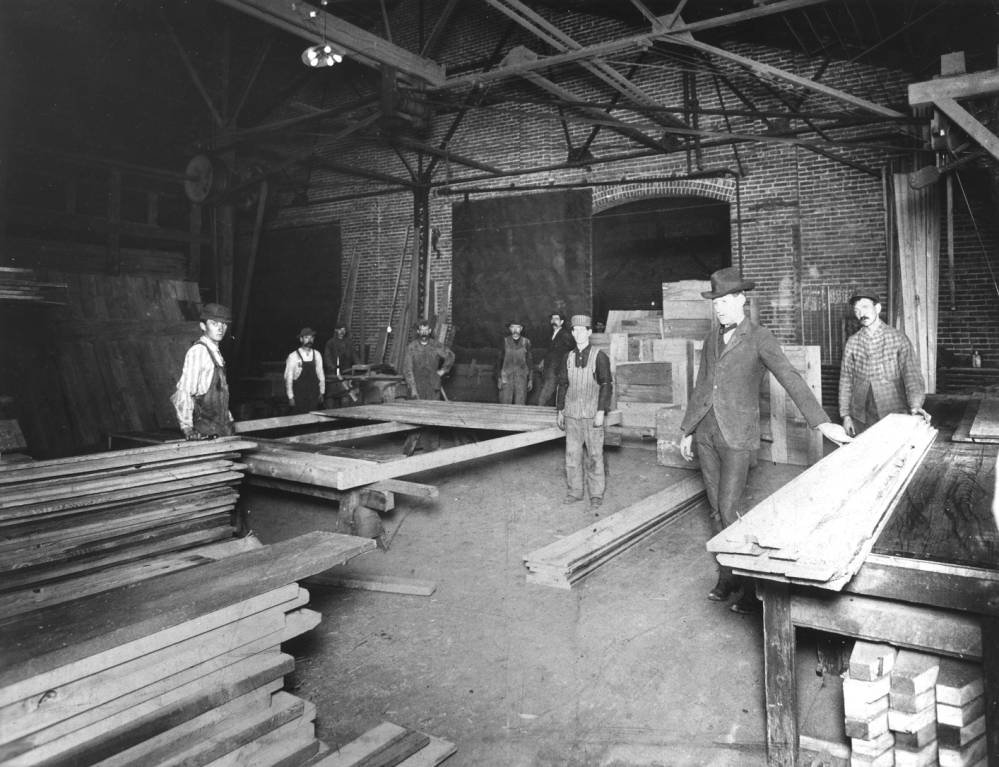

A “shop” is the group of workers necessary for the completion of certain glass patterns; at the head of each “shop” stands the blower. The first to come into contact with the glass is a semi-skilled worker called a “gatherer”. By means of dipping the end of a long, hollow iron pipe into the glass and then turning it, any desired quantity of glass can be gathered. This is rapidly carried a few feet to a bench covered with a plate of smooth, hard metal, where the glass is rolled. The gatherer then elevates the pipe and blows into it, thus beginning the shape. It is then passed to a skilled mechanic, the blower. He stands about two or three feet above the floor lever on a small, movable platform called a “dummy”. This “dummy” is equipped with the mold, and on each side of the mold are devices or pedals to open and close it.

Having placed the molten mass into the mold, the blower closes it and then blows into the pipe, turning it at the same time. When the glass has been blown to the limits of the mold confines it is removed, still on the pipe, in a bottle form, and handed to the boy who “cracks off”. At intervals several of these “bottles” are taken by another boy and placed in the lehr, a long kiln where a tempering process follows. Finally it emerges to be finished by having the rough neck cut off by a machine, and the sharp edges slightly melted to make them smooth. The article is then ready for shipment. It should be observed that in all this work there is but one fully skilled worker, who is assisted by a semi-skilled one and several unskilled juveniles. In many cases I have seen aged men, women and even imbeciles perform these unskilled tasks.

Besides this blowing into molds considerable work is done without the aid of molds. This is called working “off-hand”. In this work the pipe is used and also callipers, scissors, and wooden blocks and sticks, to fashion the desired article. In all processes of glass blowing it is necessary to have air pipes under which the molten glass is somewhat cooled before being blown.

The largest department of flint glass manufacture (clear or crystal) is the press department. Here a lump of the glass is dropped into a mold, either plain or figured, and a lever releases a plunger which fits the mold and forms an article. The figured mold is one that has been arranged by a mold maker with a pattern, and glass pressed into it receives the pattern impression. Window glass is made of much harder material, and it is rolled on long, flat surfaces. For some years past attempts have been made to manufacture glass coffins, but the cost of production is so high that this invention is as yet in the experimental stage.

DECORATING.

For high worth in a decorative sense cut and engraved glass comes first. The cutting and engraving is done when the glass is cold, or in its natural finished state. Cut glass is made both from plain and figured blanks. In the first case steel wheels called “mills”, covered by a thin layer of wet sand, fine alundum or carborundum, impress the glass with the main cuts. This is called “roughing.” The sand is then removed by various stones, both natural and artificial, with water running on them. The finer cuttings are added by the stones.

This is called “smoothing”, and of all the skilled trades connected with the glass industry it is considered the most skilled. Wooden and felt wheels and rag buffs smooth the surface, and the article is then immersed into a combination of powerful acids which produce the brilliancy of heavy cut glassware. The process from the figured blank is the same excepting the roughing, which is eliminated.

Engraved glass is done by skilled mechanics using either copper wheels or stones, and the finished product consists chiefly of scrolls, flowers and animals. It is highly artistic.

Etching by means of acids, as well as by sand blast, are still other and cheaper ways to decorate the surface of glass-ware.

FUEL.

The old Muranians used wood to produce the heat for melting a “batch” of glass. It is still used in parts of Italy, but Bohemia, Germany, Belgium, France and England depend chiefly on coal for the heating units, and in this country natural gas belts have given rise to numerous glass plants, such as those existing in Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia, Indiana, Illinois, Kansas and Oklahoma. Gas is the best fuel for the work, but in certain places it has been exhausted, particularly in parts of Maryland near West Virginia and in Central Kansas. Sometimes oil has been substituted with a measure of success, but frequently a factory will move away to another spot where nature still has gas wells spouting. An interesting case of this sort came to my notice several years ago at North Baltimore, Ohio. I had occasion to visit a cemetery there one afternoon in the fall of the year, and going across a wide field I saw the furnace of a glass house. But that was all. The holes were there, and the furnace was intact, but long grass waved at its base, and no other trace of the industry was in sight. It was a large and prosperous plant some twenty years ago, but the stoppage of natural gas caused the firm to remove to West Virginia. I cannot describe how I felt, and how lonely that furnace looked, where once the busy workers had fashioned all manner of glass, and then had departed, leaving this solitary ghost as a reminder of the past.

SCIENTIFIC USES.

Most of the ware made for the use of surgeons and chemists is done by a branch called “lamp working”. Tiny pipes are used, and the heat is derived from gas rapidly driven thru a jet. As the progress of the scientist advances so too must advance the art of the lamp worker, and all sorts of lenses, tubes, syringes, measuring glasses, thermometers and phials, unknown to the glass worker of other times, must be blown by these workers.

MACHINE INVENTION.

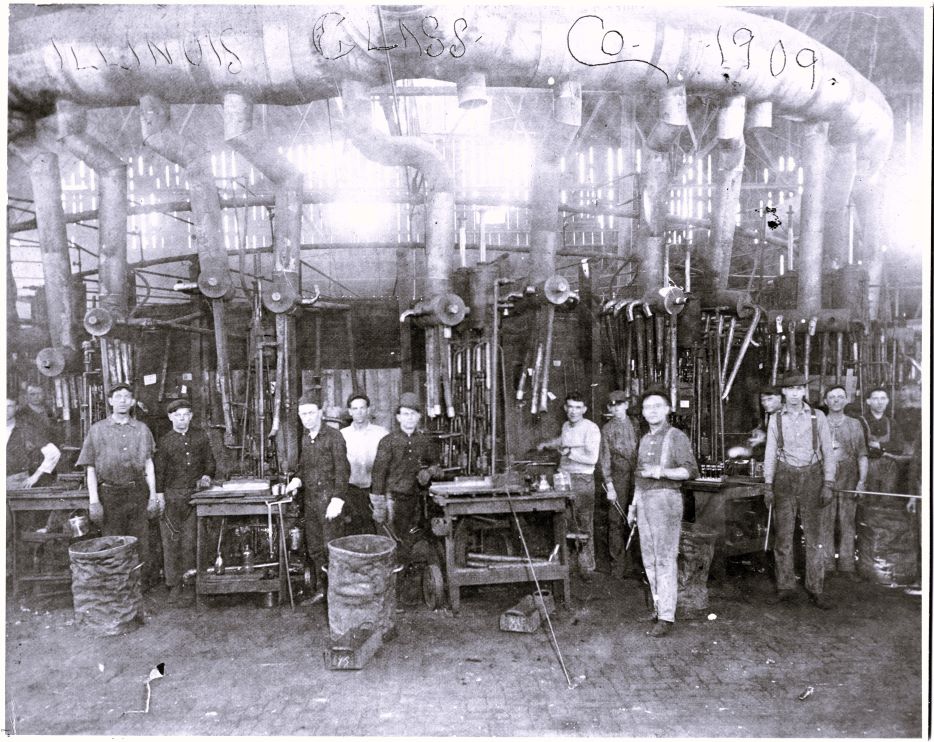

The glass industry as a whole received its share of benefit from the discovery of steam and electric power, but until 1903 the mechanical tasks of the glass worker were very much the same as they had been hundreds of years ago. In that year Michael Owens of Toledo, Ohio, invented a machine to blow bottles. It now has been so improved that any bottle from a half-ounce capacity to a 12 gallon demijohn can be automatically blown. The invention was first scoffed at by those glass workers most competent to speak for their trade, but this contempt was silenced in 1909 when 49 machines, each with six arms and a producing power of 111 gross every 24 hours, produced a grand total of 1,700,824 gross bottles. To accomplish the same amount of work by the former methods the service of 1320 stalled blowers would have been required.

As this machinery is constantly being improved it is not too much to say that the entire ancient, highly skilled and very exclusive glass trade may soon be revolutionized, and the erstwhile aristocrats of pipe, dummy and scissors reduced to the unskilled stratum, inevitable to so many crafts, and uniformly dreaded by the craftsmen. The decorating trades requiring skill have been greatly speeded up by the introduction of manufactured stones with qualities of abrasion, making for more work. The relative importance of machine inventions in this line is small, as it is rather of aesthetic value and cannot pretend to the primary social importance as the other branches of the industry.

ORGANIZATION.

I believe that the remnants of the once strong Green Bottle Blowers’ Association still command practically all of the blowers of bottles from its craft union vantage (?) point. There is no strong sentiment for a change in the form of unionism as far as the skilled workers are concerned. The hours are eight and one-half, with both day and night shifts. The wages are hardly in excess of one dollar an hour, with the general post-war tendency to decline. For many years this organization was in constant wrangling over jurisdiction rights with the American Flint Glass Workers’ Union.

The window glass workers are without an organization, with the possible exception of a few company unions, where the factory manager is also the president of the union, and as such appoints the factory committees.

The American Flint Glass Workers’ Union is the most powerful order of glass workers in this country. It grants charters to groups of seven or more employees. It is composed of glass workers of more than thirty departments of what is known as the flint glass industry. With most of its locals in the States it also has several in the Dominion. There are usually around one hundred and twenty locals, and the total membership have never exceeded 11,000. At the present time it perhaps falls short by several thousand of this mark. About seven-eights of the members are workers in the hot metal departments. They work eight and one-half hours, with alternating night and day shifts, Saturday afternoons off.

The remaining eighth is composed of cutters and engravers who work nine hours for five days and five hours on Saturday forenoon. The president of the order recently published statistics as to wages for the entire trade for the past year, the average being $34.00 per week.

In 1916, at Toledo, a movement for industrial unionism reached its zenith and its failure, when the present head was elected by a big majority on a reactionary program, defeating a bulb blower who stood for industrial unionism.

At the time of the First Convention of the I.W.W. in 1905 the Flints, then at war with the A.F. of L., which had characteristically scabbed on them, sent two delegates to the convention. They had no power to act, but the active one, then president of the union, T.W. Rowe, made a revolutionary speech, and acted thruout with much zeal. His colleague, Wm. P. Clarke, since become president, also took part in this convention. They reported to their membership, but never affiliated, subsequently forgetting their grievances against the Gompersian horde and rejoining the fold of sheep.

This organization has in the past waged many strikes, but it is now avoiding them without regard to the condition of the members. It publishes a monthly journal, which might be a good medium of education, but is kept in check by the officialdom, and its pages recount chiefly the sports of the members, bewail the loss of beer, and frequently are filled with incitation to violence against the radicals.

The Union is somewhat in advance of the tactics of Mr. Gompers in that the various departments of any one plant support the others in case of a strike or lockout. The union at present assesses its members one per cent of their wages, but in cases of necessity it goes much higher. The initiation fee is three dollars to all but foreigners, who are penalized for not having had the good sense to be born in the U.S. to the extent of ten dollars. In case of strikes or lockouts the union pays weekly strike benefits of seven dollars after the expiration of the second week.

It holds an annual convention, and an annual joint conference with the organized employers of the National Association of Pressed and Blown Glass Ware Manufacturers at Atlantic City. The officials of the union, together with executive members of the various departments, represent the workers. On these occasions the heads of the Flints and the employers hold “unofficial” meetings and compare lists and blacklists of radicals and agitators.

From the Flint officialdom to the employer’s side is but a short step, as is evidenced by the long list of Flint officials and executives who have become superintendents, factory managers, foremen, and officials of the Manufacturers’ Association. At the present time there is not a trace of progress, and but little hope can be entertained that the union will become in the near future either industrial or revolutionary.

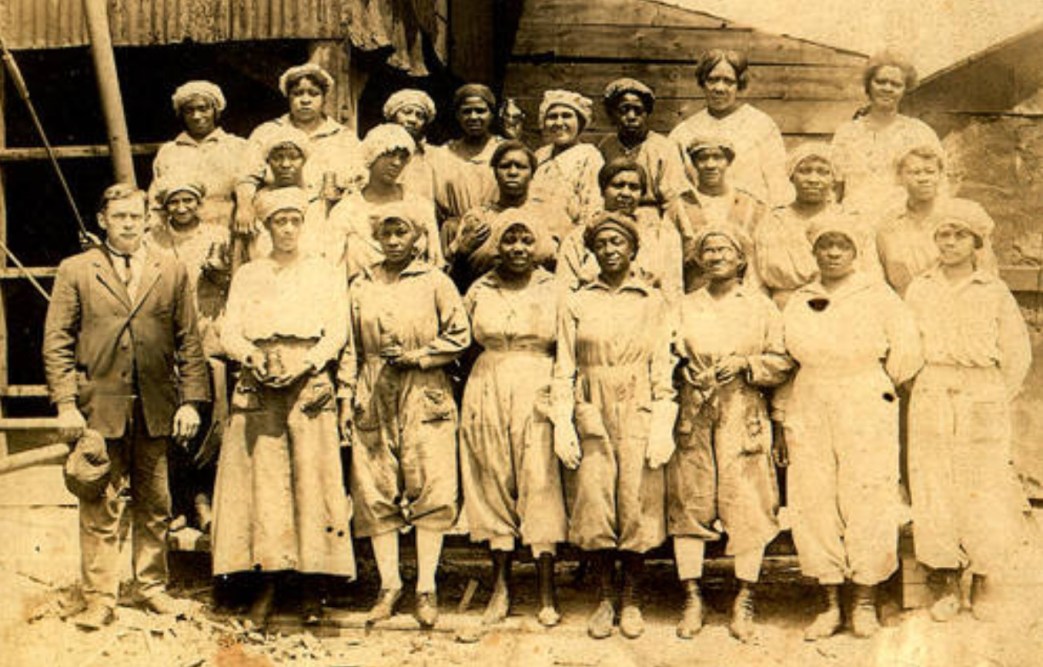

However, the Industrial Workers of the World need not view the glass factory as a place where all hope is dead, all opportunity for industrial unionism shackled; it should appeal directly to the vast numbers of unskilled who are unorganized and not eligible to membership in the Flints. When a firm employs a hundred skilled workers it probably has four hundred unskilled. No sympathetic bond exists between the craftsmen and the unskilled in a glass house, and when the boys strike the men not only work with scabs, but help to recruit them. Also, there are many non-union glass houses, such as the ones in Columbus, Ohio, Sand Springs, Okla., Dunbar, Okla., Mt. Pleasant, Pa., and elsewhere.

Child labor is widespread, which is especially appalling when one considers that many of these children work night shifts. Very small boys toil thru the weary watches of the night around infernos of molten glass, which dwarfs their bodies and ruins their lives.

In the same way that many unskilled work with the few skilled in the flint shops, do work with they them in bottle and window glass plants. The vast majority of them have only heard of the I.W.W. from the corrupt press, from craft unionists, and from all who denounce it. They regard the I.W.W. as a band of outlaws roaming about with torches of destruction, and as being confined to the wheat fields and lumber camps. They have never seen its literature, have never heard its speakers, and really dread it. The glass worker should be taught the principles of revolutionary industrial unionism. should be made to see the lines of class demarcation. He should be so educated that in every wage-earner he will recognize a fellow worker, a fellow sufferer, with the same master class over him, the same chains upon his limbs and the same shambles to rise from to industrial freedom.

It is reasonable to expect that our first appeal would find the greatest response among the unskilled, but the propaganda should not be confined to them alone. At the present time the I.W.W. can best function as a mighty machine for the dissemination of its ideas. To the great mass of divided, deluded, miserable wage slaves it should be the leaven of revolt. The wages of the unskilled slaves around glass houses being uniformly low, with speeding-up devices on all sides, the I.W.W. will find among them a fertile field for sowing the seeds of class solidarity.

At this time there is an industrial union of glass and pottery workers in the I.W.W. It must have a nucleus of active members, and therefore the fellow workers forming it should be welded together to more successfully and systematically foster the growth of industrial organization among the glass and pottery workers, for the furtherance of immediate demands as well as for the final drive against the citadels of power, pelf and place; for the consolidation of militant, class-conscious labor and the establishment of industrial democracy.

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

Link to PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrial-pioneer/Industrial%20Pioneer%20(March%201921).pdf