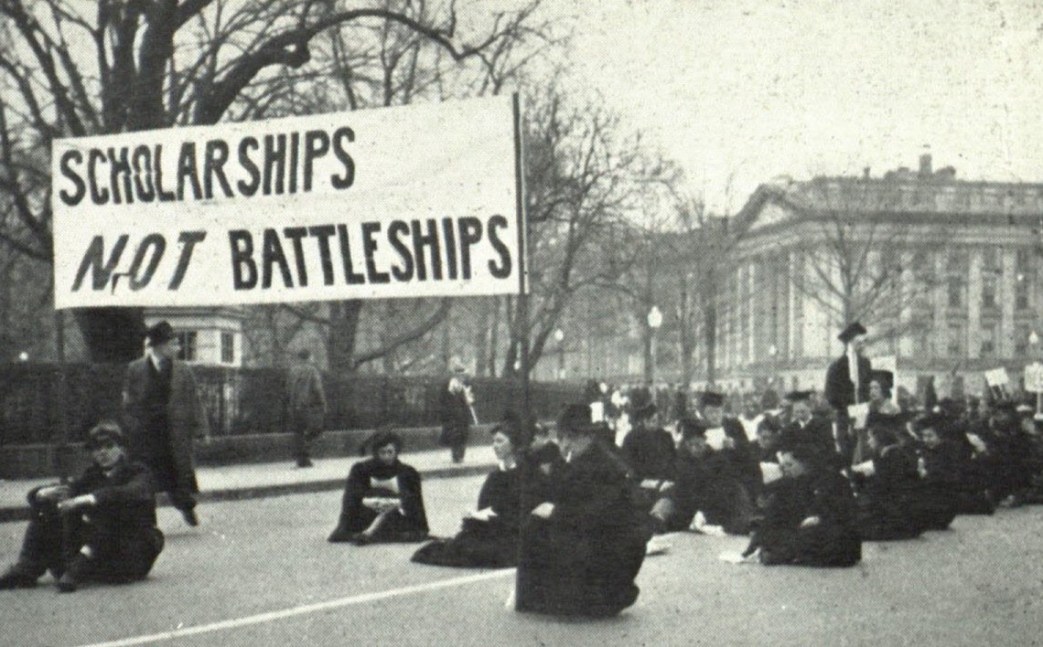

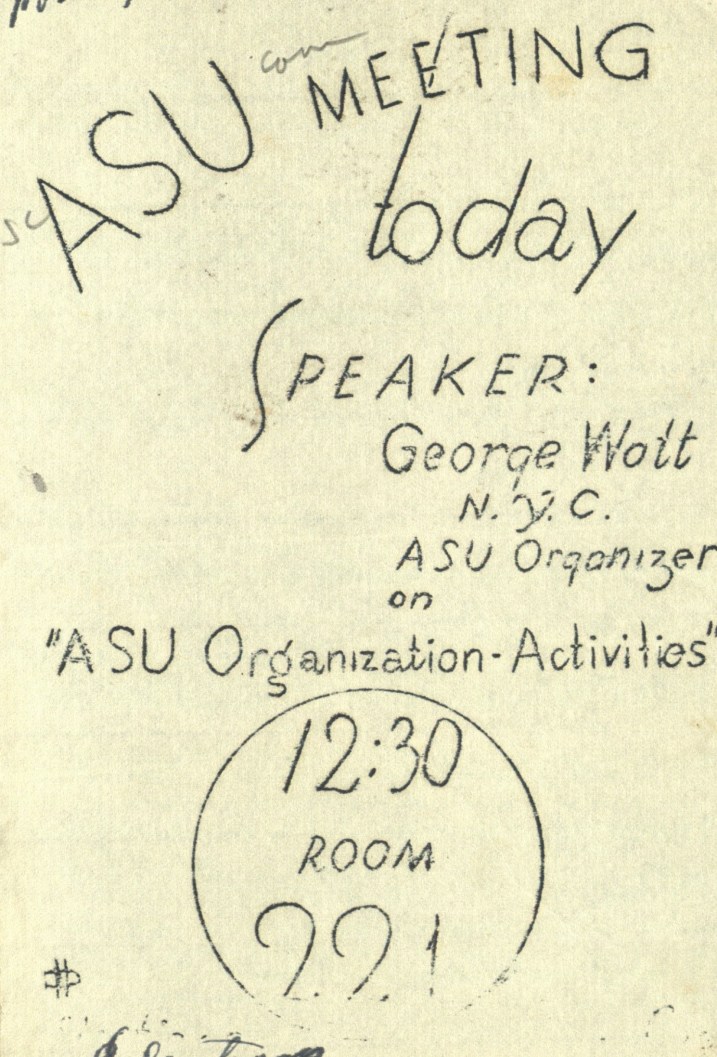

Transcribed for the first time, a young Hal Draper, then active in the American Student Union, looks at the crisis facing the ASU, with both Socialist and Communist Party participation, when the C.P. turned to the Popular Front and abandoned support for the ‘Oxford Pledge’s “refuse to support any war conducted by the United States Government”. The role of liberals, students, and political polarization are all also addressed.

‘The American Student Union Faces the Student Anti-War Strike’ by Hal Draper from American Socialist Monthly. Vol. 5 No. 2. April, 1936.

AMONG the student organizations of America, the American Student Union distinguishes itself by the boast: the ASU is the only militant student movement. It is therefore in a warning spirit that the observer must report: there are two forces sapping the militancy of the ASU–the liberals and the communists. This united front may appear surprising to those who accept the Hearstian view of the communists as the wild men of Union Square. But readers of the socialist press know what the “new line” of the Comintern means. It means an opportunism which differs from previous expressions of opportunism in this respect—that it is systematized, thoroughgoing, and imposed throughout the communist movement with the gleichschaltung of doctrine peculiar to the “monolithic” hulk that is the Comintern.

The Young Communist League students have been gleichgeschaltet. The virus is now spreading into the ASU and into the student strike.

The Trend Toward Liberal Opportunism

The key to the understanding of the trend in the ASU lies in the fact that the policy of the “People’s Front” is being applied to the student field. How easy is such an application—and how doubly dangerous! For the student movement is essentially middle-class in class base. It is therefore especially important here to retain the leadership of the working-class elements. The “tactic of the People’s Front” does just the reverse.

The “People’s Front” is designed to ally the middle-class elements to the working class by catering-kowtowing rather than aggressive leadership for working-class demands, which are also shown to be the only way out of the middle-class dilemma. The “People’s Front” restrains the working class to those demands and actions that are acceptable to middle-class liberals, it pulls the working class down to their level. A “People’s Front” can never get beyond a middle-class level (and is therefore doomed to futility), because any such attempt inevitably is declared out of order with the cry: “We shall antagonize the liberals!”

This is the situation in the ASU. The cry “We shall antagonize the liberals!” has been put into the balance against the program and traditions of the ASU and has been found weightier. And the YCL is the leader in this tendency.

The most important and most sinister example of this trend is the opposition to cooperation with, and participation in, the organized labor movement—in strikes, etc.

The old Student League for Industrial Democracy felt that one of its most important contributions to the student movement was its work in linking student struggles with labor struggles, not only through expressions of platonic sympathy, or through lectures on “Proletarian Literature and its Social Significance”, but through actual involvement of students in picketing, in strike meetings. It felt–and demonstrated–that an hour on a picket line may telescope a long process of education toward social consciousness. Its very name–Student League for Industrial Democracy—was an index to its approach. As for the National Student League, it indeed specialized in aiding the dual “red” unions.

But of all actions that “antagonize liberals”, picketing for a union on the outside is the worst. And so the damper is going down on labor action in the ASU. Not officially, by any means–by action “from below” by the YCL’ers.

A typical example from a New York high school, with regard to the elevator strike: A motion was made at the chapter meeting that the executive commit- tee be asked to make plans to help the local strikers. The recognized YCL leaders in the chapter vigorously opposed the motion on two grounds: (1) it would drive away liberal support; and (2) the strike really has nothing to do with student problems. The motion was passed over the opposition of the YCL, with a section of the maligned “liberals” voting in favor. It is doubtful whether there would have been any significant liberal opposition if the YCL had not given them the lead and the arguments. This is “vanguardism” in reverse.

At a New York college, the elevator-men were non-union. For weeks, the YCL’ers resisted involving the ASU chapter in the question of unionization, even opposing “moral support”. Here again, it is interesting to note that the non-socialist, non-communist members of the executive committee were antagonized–against the communists. However, in citing the reaction of the liberals in this case, we by no means wish to obscure the fact that a large section of liberal support is alienated by militant action. But there are liberals and liberals–we shall recur to this point later.

We do wish to emphasize that in this opposition to ASU participation in labor struggles, we see the “tactic of the People’s Front” in all its glory—a “tactic” of tagging along in the wake of middle-class prejudices.

The Oxford Pledge

If the militancy of action of the ASU is being undermined by the shadow of the “People’s Front”, even more serious inroads are being made on its anti-war program. For after all, the YCL is in favor of aiding strikes, even if YCL’ers oppose the ASU’s doing so. But the YCL is categorically and on principle opposed to the Oxford Pledge, which is the core of the anti-war program of the ASU.

This statement may be challenged: did not the YCL vote for the Oxford

Pledge at the Columbus Convention of the ASU? Let us see.

The Oxford Pledge states that we shall “refuse to support any war conducted by the United States Government”. These are not weasel words–they are unequivocal and not open to misinterpretation.

Do the communists believe that workers and students should refuse to support any war conducted by their imperialist government? Listen:

On February 7, the Daily Worker laid down the line as follows:

“Question: Would the Communist Party favor a war by one capitalist nation against another capitalist nation if the latter were of a fascist character or one that is more hostile to the working class than the former?” “Answer: The Communist Party is always against imperialist war. Its chief slogan today is the fight for peace…

“…If Nazi Germany attacks one of the small neighboring countries, like the Baltic countries, or Czechoslovakia, peace will not be aided by letting Germany win a victory. Such a victory would merely be a license for the war-makers to continue their campaign of aggression.

“In such a war, the duty of the working class of both countries would be to fight for the defeat of Germany, and this would certainly include fighting in the defending army of the small attacked country.

“The situation is even more clear in the case of an attack on the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union, France and Czechoslovakia are bound by a pact of mutual assistance against an aggressor to come to the defense of the attacked nation. Here a war by France or Czechoslovakia against Germany, coming as a result of an attack by Germany, would be a war in defense of the Soviet Union, even though France, Czechoslovakia and Germany are all capitalist countries.

“The Communist Party would vigorously support such a war because here, too, once Germany had begun the war, the defense of the Soviet Union and the defeat of Nazi Germany are the only possible road to peace…”

Yes, these are not weasel words–they are unequivocal and not open to misinterpretation. The Communists will “vigorously support” war conducted by the United States Government, if—the Government is allied on the side of the Soviet Union.

Does this really apply to the United States? Earl Browder thinks so. In his debate in New York with Norman Thomas, he stated:

“A situation can develop tomorrow when German and Japanese fascism will proceed to attack the Soviet Union…Will the militant socialists adopt a position of neutrality? Will they advocate the slogan ‘Keep America Out of War?’ Impossible!… They must have a proletarian answer, a socialist one, the defense of the Soviet Union.”

What stand will the Communist Party take when the war-triangle–America, Japan, USSR–flares up, through an attack by Japan? Call for or support war on the side of Japan? Monstrous. Raise the slogan: Keep America Out of War? “Impossible!” Well, then, they can only-call for and support war against Japan.

This is the position of the Communist Party and the Young Communist League. It is with this position that the YCL approached the Oxford Pledge and the ASU.

The first time the question came up was at the Second American Youth Congress in July 1935. The delegate of the New York SLID introduced a resolution stating that “we refuse to support any war conducted by the U.S. Government”. Serril Gerber, leader of the NSL and a prominent member of the YCL, opposed it on the grounds: (1) that it was not proper to commit the Youth Congress to the Oxford Pledge; and anyway (2) who knows, maybe the U.S. Government will fight a progressive war! The resolution was tabled–to kill it while avoiding a vote on the principle.

After the Youth Congress, there went on simultaneously (1) agitation among YCL’ers on their rejection of the Oxford Pledge; (2) negotiations between the SLID and the NSL for amalgamation, in which the SLID insisted that the Oxford Pledge was a minimum programmatic condition for any united student organization. The communist leaders were presented with the choice: amalgamation and the Oxford Pledge, or neither. Opportunistically betraying in practice their opportunism in theory, they agreed to the first.

But while the leaders reluctantly accepted, communist students agitated up to the very day of the ASU convention, against including the Oxford Pledge in the ASU program-on the ground that it would “antagonize the liberals”. At Columbus itself, YCL delegates at the SLID convention (held directly before that of the ASU) voted against including the Pledge in the ASU program. And then at the ASU convention, all YCL’ers carried out their compact and voted for it. No wonder (we are told we obviously cannot vouch for it) most of the YCL caucus at Columbus was devoted to an explanation of their war line!

The ASU was, programmatically speaking, a “shot-gun” wedding. It did not lead to programmatic faithfulness.

Not that the YCL openly disavowed the Oxford Pledge! That would have been inexcusably stupid! The correct tactic was “merely” to leave it on paper as much as possible. And the means was at hand: “We must avoid antagonizing the liberals.”

Was it proposed that the ASU use the Pledge as a plank in its campaign for control of a Student Council? The communists opposed it for fear of losing liberal support. Was it proposed that the ASU seek to incorporate the Pledge in the program of an anti-war committee or league? Ditto. It was even proposed that the Oxford Pledge be dropped completely from the special program to be written for the high school section, because it hindered legal recognition by the administration. On this point, a compromise was reached, whereby it was retained, with an “educational approach”.

And Now the Student Strike

All these forces are at work on the ASU as it faces the third Student Strike Against War this April.

For the last three years, the question aroused by the strike was: why call a strike? Or anyway, why do you have to call it a strike? Won’t a peace assembly or some other non-strike action be just as good?

The answer of the militant student movement was: Only a strike can achieve what we want. Why?

1. Because only such action is a preparation-a “dress rehearsal”, “fire-drill”, we called it–for the kind of action we shall have to take in an actual war crisis.

2. All year around, we hold peace meetings to listen to speakers tell us why war is no good; on Strike Day we act. The strike is a break with routine–the participant takes a step unusual for him, just as we shall most assuredly have to break with routine methods when faced with war. It leaves a definite impress upon the striker himself, which is the result of education through action. And it gives him a foretaste of the sort, and sources, of opposition he will have to meet, when the prevalent pacifism gives way to a pervading “patriotism”.

3. The spectacular quality of a strike has a stimulating effect upon the people at large, which reacts healthfully upon the students themselves in showing them that they can be a significant force.

For these reasons not even the most completely independent and student-controlled “peace assembly” is an adequate substitute for the strike. But even last year, individual NSL and also SLID chapters disgraced themselves by accepting as substitutes administration compromises which were emphatically worse than nothing. It is a positive blow to the true anti-war movement when the very people (certain school heads, etc.) who will lead us into the next war are built up as “peace-lovers” on Strike Day.

This year, obviously even more, we are faced with the danger of typical “People’s Front” demonstrations and meetings instead of anti-war strikes. The YCL, we understand, is officially backing the slogan of no-substitute-for-the-strike in the colleges, just as it officially supported the Oxford Pledge for the ASU, but we can expect the logic of the “People’s Front tactic” to have its own way to an alarming extent.

This danger has already been indicated (by the middle of March) in two ways.

1. The original draft of the college strike call came out squarely for the Oxford Pledge. The inevitable objections came from prominent liberals; whereupon the YCL student leaders attempted to get the Pledge dropped from the call. Here again, a compromise was reached, the Oxford Pledge being retained but de-emphasized.

2. The National Administrative Committee decided that its call for the high schools would not call for a strike, but for a “peace action” on the basis of certain minimum conditions. After debate, the YCL’ers agreed to compromise to the extent of inserting in the body of the call the statement that the preferable form of peace action was a strike. The YPSL, on the contrary, supported the proposition that the high-school call be directly for a strike, though willing to concede that this year, because of the weakness of the high-school ASU, we state that we shall accept independent student-run assemblies.

To give up the call for a strike, we felt, was an impermissible step for a number of reasons:

(1) Those few advanced schools where a strike was possible would tend to be dragged down to the level of the more backward schools.

(2) Even where a strike was not possible (and experience has shown one cannot always tell in advance without trying), we must always keep in the forefront the idea that the strike is our real goal. To give up the strike call this year will do more to destroy an orientation toward a future strike than can be counteracted by any compensatory educational work. We must call for a strike for the sake of the future if not the present.

(3) The opponents of the strike call maintain that we shall be in a stronger position to call a strike after we have demonstrated that the administration refuses to allow an assembly. The idea is that the vacillating elements will say: “Well, the ASU did its best to reach a compromise; the only thing left to do is strike.” But the danger is that we shall thus be building up, whether we want to or no, the idea that a strike is “justified” only after a “reasonable” action has been denied. There is also the danger that after we have built up liberal support for a peace assembly on our conditions, and after the demand is rejected, that liberal support will not carry over for a strike, but will rather press us to give up our conditions. The only way to counteract these tendencies is to call for a strike first and negotiate afterward.

(4) Even where it is not possible to go through with a strike, the more strike sentiment we build up, the more chance we have of getting a student-run assembly. In “practical” terms, we use it as a bargaining point. Phrased otherwise, we utilize pressure from the left to arrive at a more satisfactory resultant offences. This is another example that opportunism is not even good “practical politics”.

Over the vigorous opposition of the YPSL, the peace-action call was adopted by a united front of the YCL and liberals, in which the lines blurred. They likewise rejected a proposal to call for a strike in the New York district only.

This decision, even more significant as a signpost than for its content, must be fought in every district and chapter (which have autonomy on the question) by all militant students.

Should We Be Afraid of Polarizing the Student Body?

We have repeated–perhaps too often–that the tag-line of “People’s Front” opportunism is: We Must Not Antagonize the Liberals. There is a variation on this theme. It runs: we must not picket, call for a strike, push the Oxford Pledge, etc., because to do so would polarize the student body—i.e., the militant students would gravitate in one direction, the rest of the students would be repulsed in the other direction, and it would be so much harder for us to reach them.

What is the meaning of such polarization? Is it an unmitigated evil? or do we want to polarize the students? Let us first understand how socialists must look upon a student movement.

First of all, the students are not a class by themselves. They have no common class interests to weld them into a homogeneous whole. A student organization is necessarily a mixed-class organization, predominantly middle-class in composition at that, which means that there are divergent, directly contradictory class forces acting upon it, that it is pulled in different directions at the same time.

Students as a group face two ways: one way is toward the working class and what it stands for; the other way is toward the ruling class. The first orientation determines the progressive section of the student body; the second orientation the reactionary section. The “swamp” in-between tends to line up with the camp that gives the boldest lead.

In this situation, the task of an organization like the ASU is to organize the progressive section of the students as an eventual ally of the working class, not to be diverted from this task by the reactionary elements or by the “swamp”. It is not we who wish to polarize the student body; it is capitalist economy that has done so; the polarization that takes place on the student field is merely a reflection of that in society as a whole.

The meaning of this fear of polarization then becomes plain. Polarization in society i.e., the intensification of class antagonisms-can be avoided only by the capitulation of the working class. Polarization on the student field can be avoided only by the capitulation of the militant elements to the “swamp” and through the “swamp” to the enemies of the working class.

This is the inner meaning of the trend in the ASU. This is the meaning of the “tactic of the People’s Front”. In this inexorable operation of class forces, good intentions are only an evidence of political blindness.

Socialist Review began as American Socialist Quarterly in 1934. The name changed to Socialist Review in September 1937. The journal reflected Norman Thomas’ supporters “Militant” tendency of the ‘center’ leadership. Beginning in 1936, there were also Fourth Internationalists lead by James P. Cannon as well as the right-wing tendency around the New Leader magazine also contributing. The articles reflect these ideological divisions, and for a time, the journal hosted important debates. The magazine continued as the SP official organ through the 1940s.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/socialist-review/v05-n02-apr-1936-soc-rev.pdf