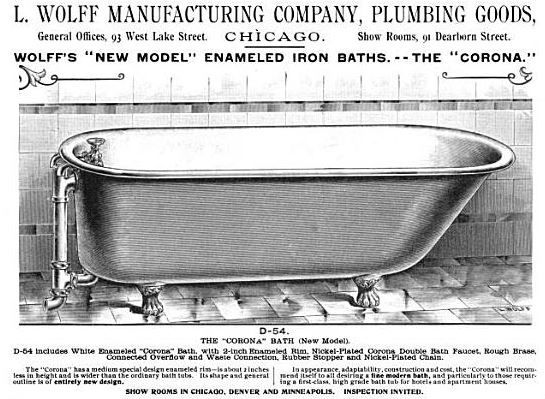

How dangerous is making a bath tub? Potentially fatal. 176 workers making bath tubs at Chicago’s L. Wolff Manufacturing Co. went on strike against the toxic conditions wrecking their and their families health in December, 1912. Mary Gray Peck of the Women’s Trade Union League investigates the dangers of enameling and what other countries, with stronger labor movements, were doing to address the problem.

‘Bath Tubs and Their Makers’ by Mary Gray Peck from Life and Labor (Women’s Trade Union League). Vol. 2 No. 5. May, 1912.

One hundred and seventy-six iron enamellers went on strike in the L. Wolff Manufacturing Company’s plant in December, 1911, because the conditions, they said, were dangerous to health, and because they could not earn a living wage. Enameling is a difficult and dangerous process, in which lead, arsenic and other poisonous chemicals are used. It is dangerous even when the latest safety appliances are employed.

In the Wolff factory, there were not even lavatories for washing the enamel powder from the hands, and the men were obliged to eat while they worked. The Wolff Company paid the men frequently as low as $7.50 a week, and sometimes less.

The L. Wolff Manufacturing Company, Chicago, now under investigation by the United States Government re the Bath Tub Trust, is a millionaire concern too well known throughout the country to need further description. It employs thousands of workmen. A small force, less than 200 of these, is required for the dry enameling of bath tubs and other articles. This force is divided into eight-hour shifts, going to work at 7 a.m., 3 p.m., and 11 p.m. The men work continuously throughout their shifts, taking their food as they can while the tubs are in the furnaces. They are chiefly Poles and Bohemians, with some Lithuanians, Slovaks, Hungarians, Croatians, and two Germans. Formerly, dry enameling was done by American workmen at from $4 to $7 a day. Then German enamellers displaced them at lower wages, only to be underbidden, after a while, by the still cheaper labor of Eastern Europe. Work by the day was changed to work by the piece, and the inspector added the element of uncertainty to the system.

The wage two years ago was from $25 to $35 for two weeks’ work, or from $12.50 to $18.50 per week. Now, the wage runs from $15 to $25 for two weeks, or from $7.50 to $12.50 per week. It not uncommonly goes below $7.50. In addition to this enamellers are in an un healthy occupation, and occasionally are laid off for sickness. This sickness usually is some form of that deadliest of occupational diseases, lead-poisoning. Illness entails the double expense of lost time and doctors’ bills. Plumbism or lead-poisoning is a subtle disease which all authorities recognize as peculiarly transmissible in its effects to the children of men or women suffering from it. This means sickness and doctors’ bills for the families. All this to be paid out of $7.50 a week. All this for the sake of from $7.50 to $12.50 a week, for as long as the enameller lasts to earn it. After that, the trade is through with him, and the community in which he is stranded must support him and his family.

In order to understand the full misery of the case of enamellers, it is necessary to know how dry enamelling is done, and to contrast the conditions under which it is done in the American factories with those prevailing in the foreign countries from which these men have come.

The Gas Problem

The first thing to be considered in the process of dry enamelling is the manufacture of the enamel powder. The powder is made in the factory, and the secret of its formula is jealously guarded. Only the chemist knows what the combination is. There are many formulae for making enamel powder, but the general constituents are the same. Soft glass is used as the foundation, to which the white color is given by certain chemicals, such as tin or tin-lead oxide, arsenic, fluorine, or aluminum combinations, while lead-salts are used to give elasticity, lower melting point and the “sheen” so much desired. These materials are mixed and poured into crucibles to be melted. During the melting, chemical changes take place, which set free poisonous gases. Among these are vapors of arsenious acid, of fluorine, muriatic, sulphurie, nitric, carbonic acid, etc. If these gases escape into the room where the enamelling is done, they must be breathed by the men. In foreign factories, hoods and forced draughts are installed to carry off the fumes. Fluorine is a highly dangerous chemical to inhale. It is used in etching glass, and the fact that fluorine and other corrosive gases are constantly present in enamelling shops is proven by the state of the glass windows. These soon get to look as if they had been ground, and the enamellers state that when they get too dull to transmit enough light to work by, one of the men breaks out a pane or two, so that fresh ones will be necessary. But what about the lungs that breathe that atmosphere, year after year? You can’t take cut a man’s lungs and put in fresh ones as you change a pane of glass.

The Heat and Dust Problem

After the elements have been fused in the crucible, the fluid mass is run out into water and allowed to harden. This mass is called the “fritt.” Employers always say that lead which has been combined in the fritt has lost its poisonous qualities, and “can be breathed with safety.” But it has been proven by investigation and analysis in England, that this is not so. The temperature is not high enough to change all the lead, and lead is sometimes added when the “fritt” is ground up into enamel powder. This pulverizing of the “fritt” is done in mills, and unless they are tightly sealed, which is seldom the case, the dust escapes to be breathed by the mixers. When the “fritt” is ground the mixers take the powder from the mills and carry it to the enamel rooms. This is a very dusty job, and bad for the men who do it. A bath tub enameller uses about 200 pounds of enamel powder and finishes about 10 tubs in a day.

As soon as the iron tub is ready for the enamel, it is placed in a furnace and brought to a white heat. It is then drawn out of the furnace upon a table, where three enamellers usually work together upon it. These men have to work with great speed and accuracy before the glow gets out of the metal. They are protected from the intense heat by thick felt aprons, padded with asbestos, asbestos shields upon the arms, and padded asbestos mittens. In their teeth they hold a board shield with holes for the eyes to look through, which protects the face but allows the eyelids to get scorched. The heat affects the eye-sight so that enamellers are rejected from the army because of defective vision. The heat, also, sometimes blisters the arms through the thickest shields. Bending over the tub, the enameller takes an electric or pneumatic or hand sieve and distributes the powder over the white-hot surface. The sieve has to be constantly shaken or beaten with stick to keep it from clogging with dust. The enamel melts on the hot iron and gives off fines, and this in combination with the heat and the dust from three sieves shaken close to the face and the gases from the crucibles is about as malignant a condition for the lungs as could well he devised. As soon as the first coat is put on, the tub goes back into the furnace to be reheated for the second coat.

The cost of the tub varies according to the number and quality of the coats of enamel. The last coat is especially difficult to put on. The men are obliged to bend over with their faces fairly inside the tub and to work with the utmost nicety. A little dirt, a tiny bubble hole in the enamel is noted by the inspector, and the tub is thrown out. Although it is hard for eyes which have been strained in intense heat for hours to detect bubbles, and although the enameller is not to blame for dirt in the powder, the men say they receive nothing for defective tubs.

America Contrasted With Bohemia

The exhausting and debilitating effects. of such work as this under the best conditions is grave enough. In Bohemia and Germany, the enamellers say, there are hoods and forced draughts for carrying off the heat, fumes and dust, so that they shall not be breathed by the workmen. When it is remembered that this dust consists of ground glass, with arsenic and other poisons and 10 per cent of lead in it, there is seen to be good reason for the precaution. The floor is washed clean from the powder twice a day; lavatories where the men must wash before eating are obligatory; a clean room in which to eat is provided. Contrast with these foreign conditions those obtaining in our great American establishments. Here there is no attempt to carry off heat, dust or fumes. The men work continuously during their shifts, and eat or use tobacco as they work, with their hands and clothes and mouths covered with the white dust, with powder sieves shaken all around them, with dust lying thick on the unwashed floor, with the garlicky odor of arsenic in the air as an appetizer! Instead of being washed up, the floor of the enamelling rooms are carelessly sprinkled and swept, the dust being left in corners and under immovable articles. The heat with the furnaces going and the tubs on the tables, as is the case throughout the whole 24 hours, in summer is unbearable. The men are frequently overcome with it, and have to rush out into the air, or be carried out. And yet, when the Factory Inspector ordered the installation of hoods and draughts over the enamelling tables in a certain plant, the Company said it was impossible because it would cool the tubs. In the gospel according to Capital, it is better to broil a man than to cool a tub. It costs less to get another man than it does to reheat the tub.

Lead-Poisoning in the Trade

Working in lead dust without safety appliances is almost certain destruction. Lead poisoning is usually subtle and gradual in its approach. The victims do not attribute their waning vitality to the true cause until an advanced stage of the disease. It begins with loss of appetite, nausea, anemia, yellowish pallor, constipation, headache, and goes on to involve the bronchial tubes and lungs, produces wasting and paralysis of the muscles, kidney disease, “wrist drop,” and the characteristic paroxysms of “lead colic.” The victim may live on, a broken-down wreck, or he may die from disease of the respiratory, digestive, blood-making or excretory organs. The inherited effects of lead-poisoning are shown in figures gathered by Sir Thomas Oliver, for many years engaged in investigating the lead processes used in British and European manufactories, and published by the U.S. Department of Commerce and Labor, Bulletin 95, July, 1911. To quote but one example and that a moderate one, 40 per cent of the children of English paintgrinders die in convulsions during the first year of life. The proportion of miscarriages to births is much higher than this. In this country when an enameller breaks down, he goes, and a healthy man is imported from Eastern Europe to take his place. The broken-down man stays in America, and the wrongs of the fathers are visited upon the children.

The Wives and Children

To return to the Wolff strike, enamellers went on strike for better conditions and higher wages and when the strike had lasted six weeks, it was reported that the wives were urging their husbands to go back to work on any terms. Acting on this report, the Chicago Women’s Trade Union League called a meeting of the enamellers’ wives at the strike headquarters. Wednesday afternoon, January 24. The hall was filled with women and children who came in response to the invitation.

After the Trade Union speakers had talked, the chairman of the meeting asked if any of the enamellers’ wives would like to speak. Immediately, without hesitation or self-consciousness, one after another of the women came forward and spoke. One of them spoke in German, so I understood what she said. All of them spoke with passionate earnestness, some with a dramatic intensity that broke through the barrier of an unknown tongue, and made it plain that these women were not urging their husbands to go back to work on the Wolff terms. They had come to the conclusion that they and their children might as well starve quickly as slowly.

Some of them spoke with difficulty, the tears streaming down their cheeks as they pointed to the children playing on the floor. Some spoke with head thrown back and blazing eyes. But there were no hysterics and no weakening. They were facing the crisis of their lives, and they faced it well.

Since writing the foregoing, the enamellers’ strike has come to an end. About half the men were taken back by the company at once, and the rest have gradually followed. Conditions will be improved somewhat, as ordered by the State Department of Factory Inspection but not to the extent demanded. Wages also will be somewhat advanced.

The outcome of the strike but emphasizes anew the necessity of concerted action so tellingly illustrated in the English coal miners’ strike, which now is paralyzing Great Britain and threatening to stop the wheels of trade in Europe.

Life and Labor was the monthly journal of the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). The WTUL was founded by the American Federation of Labor, which it had a contentious relationship with, in 1903. Founded to encourage women to join the A.F. of L. and for the A.F. of L. to take organizing women seriously, along with labor and workplace issues, the WTUL was also instrumental in creating whatever alliance existed between the labor and suffrage movements. Begun near the peak of the WTUL’s influence in 1911, Life and Labor’s first editor was Alice Henry (1857-1943), an Australian-born feminist, journalist, and labor activists who emigrated to the United States in 1906 and became office secretary of the Women’s Trade Union League in Chicago. She later served as the WTUL’s field organizer and director of the education. Henry’s editorship was followed by Stella M. Franklin in 1915, Amy W. Fields in in 1916, and Margaret D. Robins until the closing of the journal in 1921. While never abandoning its early strike support and union organizing, the WTUL increasingly focused on regulation of workplaces and reform of labor law. The League’s close relationship with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America makes ‘Life and Labor’ the essential publication for students of that union, as well as for those interest in labor legislation, garment workers, suffrage, early 20th century immigrant workers, women workers, and many more topics covered and advocated by ‘Life and Labor.’

PDF of issue (complied file): https://books.google.com/books/download/Life_and_Labor.pdf?id=epBZAAAAYAAJ&output=pdf