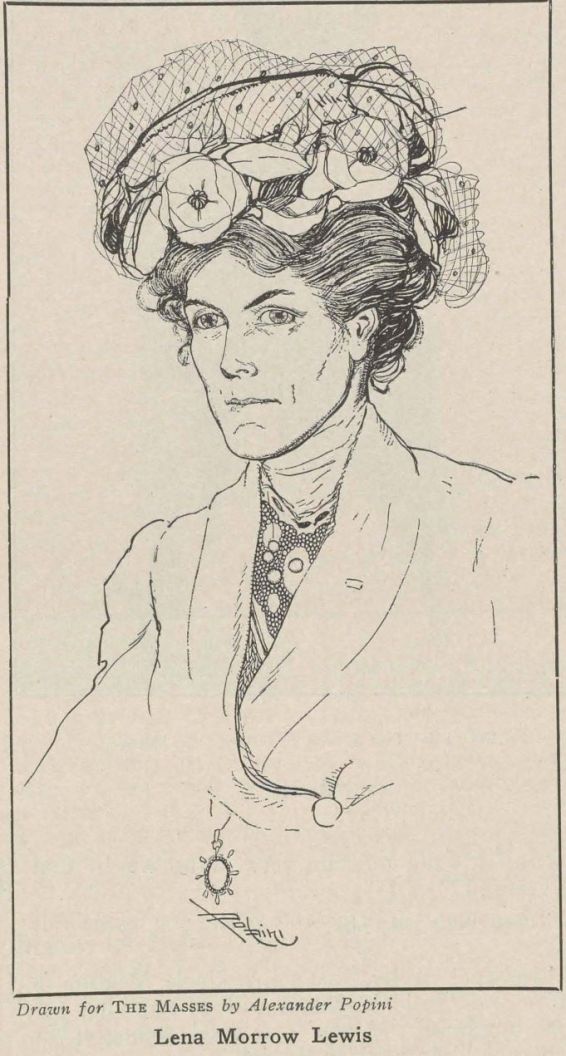

What socialist feminism sounded like in 1911. Lena Morrow Lewis was a leading suffragette, a central leader of the Socialist Party, the first woman elected to its National Executive, and prolific speaker who spent her life in the Socialist movement.

‘Lena Morrow Lewis: Agitator’ by Ethel Lloyd Patterson from The Masses. Vol. 1 No. 7. July, 1911.

Something About Her Wonderful Work for the Socialist Party

SHE is a very little woman to be the secretary of a very large association. At first glance one might think she could slip into almost any state in the Union and nobody would know she was there. But it so happens Mrs. Lena Morrow Lewis is not that sort of person. When she is anywhere people are liable to know she is there. And in the course of the last seventeen years she has been in a lot of places. At first as an agitator of the equal suffrage question, and then after developing into a socialist, as secretary of the National Socialist Association. From the lumber camps in the North to the alkaline roads of Mexico, and from the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans, she has carried her propaganda into practically every state in this country, and people knew she was doing it, too. Her work has had results.

“But,” Mrs. Lewis explains “the price I personally have paid has been to relinquish any and all ideas of a home. Not that it matters. I am used to it now. But I have rather a record; don’t you think? Seventeen years touring as a lecturer, and in all that time I have never slept for fourteen consecutive nights in the same place. I have rested for ten or twelve days and nights. But that is the longest. I have not as yet touched the two weeks mark.

“Out in California I have a very dear woman friend who lives there with her family. In her home, when I visit her, I feel as nearly as though I were in my own home, as I do anywhere. But to be truthful I have quite forgotten the sensation of having personal belongings about me other than my clothing.”

It was in 1892 that Mrs. Lewis first became active in the Suffrage movement. In 1898, in South Dakota, she made herself decidedly felt in a suffrage campaign that was then waging. In 1900, in Oregon, she became exceedingly active as a leader of the Six O’clock Closing Association, and a member of the Equal Suffrage Party. Mrs. Lewis was the first person to agitate suffrage in the Labor organizations, and to point out the advantages of organization among the various suffrage factions. In 1902 she joined the socialistic movement, and chose, as the first field for her propaganda the lumber camps of the North.

She is a slight woman with ridiculously small hands and feet. She will tell you, if you ask her, that many persons have called her “masculine.” Just why anyone should apply that adjective to Mrs. Lewis is not very apparent. Unless it is because of her voice. That, strangely enough for one whose life work depends more or less upon it, is husky and deep, devoid of the lighter feminine tones. It may carry far from a platform. In ordinary conversation it does not carry at all. Already–for Mrs. Lewis is still undeniably young–long days in the sunlight and wind have left a fine tracery of lines upon her face. Her eyes, direct and round, gaze steadily from behind her gold-rimmed glasses. She speaks slowly, but she wastes no words.

Perhaps some of the most interesting of Mrs. Lewis’ views are expressed in connection with the two subjects nearest her heart, woman and economic equality.

“There can be no real love until men and women are economically equal.” Mrs. Lewis said recently: “Under existing conditions woman cannot make a free choice of a husband. She would be more than human if she could. Of course there are women who believe their hearts are not influenced by anybody’s pocketbook; there are even women of which this is true, but they are rare exceptions.

“When a woman is courted by two young and attractive men and one man is practically penniless and the other is the son of a banker she will quite naturally choose to marry the latter every time.

“She thinks it is her heart speaking; she may really believe it is the banker’s son that she loves, but it, in nine cases out of ten, is her economic dependence working subconsciously.

“How can woman love truly and disinterestedly while the roof over her head and the very food she puts in her mouth are dependent upon the man she may marry? How can we place real love within the reach of the many while the large majority of women are practically nothing but the personal property of some man?

“Most of us never think of a woman as an individual. Our habit of thinking of her as belonging to some man is so deeply rooted we scarcely realize how it has become second nature. To most of us every woman is either some man’s daughter or some man’s wife. In the marriage service the minister pronounces the couple ‘man and wife.’ Why not ‘man and woman?’ Or even ‘husband and wife?’ It is because the word ‘man’ includes every relation–that of husband and father and son.

“But a woman must be definitely a ‘wife,’ a ‘mother,’ or a ‘miss’ to signify her property relation to some man. Can there be equal love–which is the ideal love–between the slave and her master?

“Fortunately the hope for an ideal relationship between man and woman looks bright. Men and women have more in common as human beings than they have differences consequent upon sex. As the pallid heroine has passed into oblivion and the physically and mentally healthy modern woman has taken her place men have been forced more and more to concede the equaity of the sexes. Given economic equality and our battle is won. I mean the possibility of ideal marriage becomes a certainty, and the perfect romantic love something we may each possess.

“A well-known English author and student of social and economic problems said, a few days ago, that the chivalry of the present tends more toward contempt than reverence. I agree with him. Why should men rise to give me a seat in a car and refuse to give me a vote upon the laws which govern me? If there is anything of real reverence in their attitude, certainly it is not for my mentality.

“There is no more reason why a man should rise to give a place to a young and healthy woman than that she should rise to give her place to him. They should each do so cheerfully for an old person of either sex, but on the grounds that a young person is better able to stand than an old one, and unquestionably some respect is due to age.

“In the perfect marriage, man and woman will contribute equally to the home, spiritually, mentally and economically. The equal home is the dream of the future, as is the perfect romantic love.”

From all of which you can see for yourself that Lena Morrow Lewis has learned both to say something and to saw wood, during her sojourns in the lumber camps.

The Masses is among the most important, and best, radical journals of 20th century America. It was started in 1911 as an illustrated socialist monthly by Dutch immigrant Piet Vlag, who shortly left the magazine. It was then edited by Max Eastman who wrote in his first editorial: “A Free Magazine — This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine; a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable; frank; arrogant; impertinent; searching for true causes; a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found; printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press; a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers — There is a field for this publication in America. Help us to find it.” The Masses successfully combined arts and politics and was the voice of urban, cosmopolitan, liberatory socialism. It became the leading anti-war voice in the run-up to World War One and helped to popularize industrial unions and support of workers strikes. It was sexually and culturally emancipatory, which placed it both politically and socially and odds the leadership of the Socialist Party, which also found support in its pages. The art, art criticism, and literature it featured was all imbued with its, increasing, radicalism. Floyd Dell was it literature editor and saw to the publication of important works and writers. Its radicalism and anti-war stance brought Federal charges against its editors for attempting to disrupt conscription during World War One which closed the paper in 1917. The editors returned in early 1918 with the adopted the name of William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, which continued the interest in culture and the arts as well as the aesthetic of The Masses. Contributors to this essential publication of the US left included: Sherwood Anderson, Cornelia Barns, George Bellows, Louise Bryant, Arthur B. Davies, Dorothy Day, Floyd Dell, Max Eastman, Wanda Gag, Jack London, Amy Lowell, Mabel Dodge Luhan, Inez Milholland, Robert Minor, John Reed, Boardman Robinson, Carl Sandburg, John French Sloan, Upton Sinclair, Louis Untermeyer, Mary Heaton Vorse, and Art Young.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/masses/issues/tamiment/t07-v01n07-jul-1911.pdf