Escaping from this cul de sac has been a central, and unfulfilled, task of the U.S. workers’ movement since the Civil War. Marxist historian George Novack on the particular history and role of the ‘two party system’ in the United States.

‘The Two Party System’ by George Novack from New International. Vol. 4 No. 9. September, 1938.

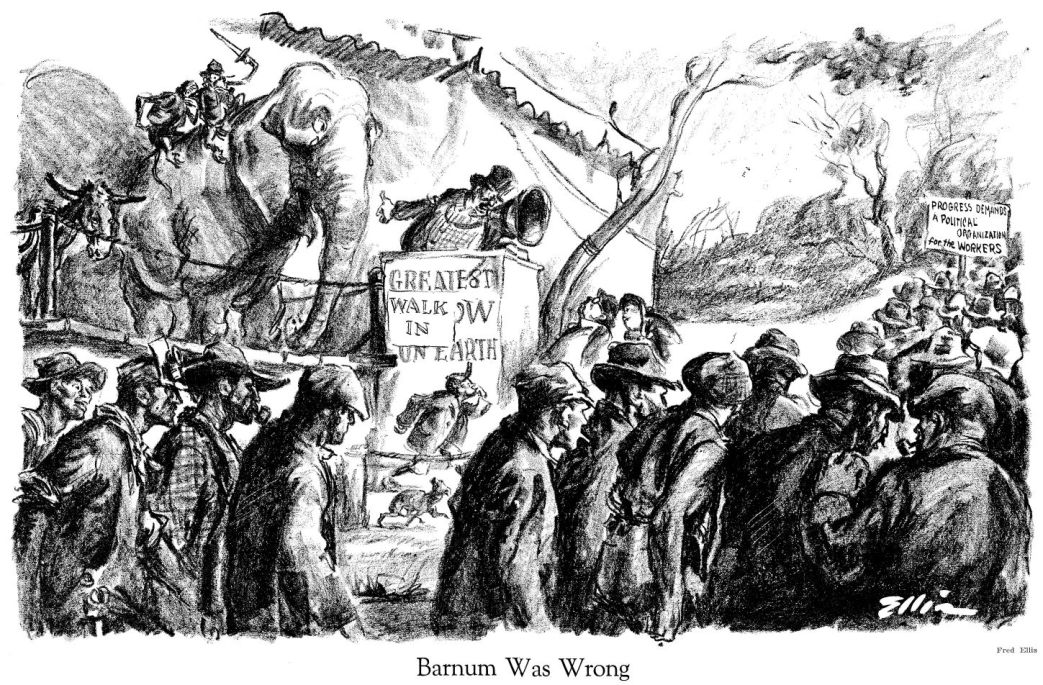

The political spokesmen for the plutocracy foster two ideas which help perpetuate their authority over the minds and lives of the American people. The first, which is the essence of democratic mythology, is that either one or both of the two capitalist parties have a classless character. The second is that the two-party system is the natural, inevitable, and only truly American mode of political struggle. The Democratic and Republican parties are given the same monopoly over political activity as CBS and NBC have acquired over radio broadcasting. The theoretical underpinning of The Politicos is constructed out of these two propositions which Josephson affirms in a special version of his own. The central thesis of his book is that “neither of the two great parties in the United States” was “a class party”, such as were common in Europe. They were competitive cartels of professional spoilsmen independent of all classes and primarily concerned with looking out for themselves and their political outfits. Only incidentally, as it were, did they also cater to the plutocracy or to the people.

By 1840, Josephson remarks, “the professional or ‘patronage’ party had been forged in America, had become part of the fabric of government itself, wholly unlike parties elsewhere which labored primarily for ‘class’ or ‘ideas’.” Further, “the historic American parties were not ‘credo’ parties, as Max Weber has defined them, parties representing definite doctrines and interests or faiths in a church, or a monarchical or traditional aristocratic caste principle, or a rational Liberal Capitalist progress; they now paralleled and competed with each other as purely patronage parties.”

This is an utterly superficial and one-sided appraisal of the bourgeois parties. While it is true that in the classic land of Big Business, politics itself became the biggest of Big Businesses, the two great political firms that contended for possession of the enormous privileges and prizes of office were no more independent of capitalist interest and control than are the two mammoth broadcasting corporations. On the contrary, they vied with each other to render superior service to their employers.

The all-important point is that the big business of politics was at one and the same time the politics of Big Business. This applied in petty matters as well as in the most vital affairs, whether it was a question of assigning a local postmastership, fixing tariffs or declaring war. The real relations between the party Bosses and the capitalist moguls were similar to those between an agent and his principal. While executing the orders of their employer and attending to their affairs, the agents, who were powers in their own right, did not hesitate to pocket whatever they could for themselves and their associates. The ruling caste was willing to wink at these practices, even encourage them, so long as they were not too costly or did not create a public scandal.

Josephson’s theory, however, not only denies this intimate relationship but even inverts it. According to his conception, it was not the capitalists but the party bosses, not the big bourgeoisie but the party which was politically paramount. Josephson invests this thesis with a semblance of plausibility by drawing a whole series of incorrect conclusions from a number of indisputable but isolated facts of a secondary order. From the relative autonomy of the party organizations, he deduces their absolute independence of the ruling caste; from the episodic antagonisms of particular bourgeois politicians to certain demands, members, or segments of the capitalist oligarchy, he deduces a fundamental opposition between them.

The Relations Between Party and Class

Throughout his work Josephson displays a very meager understanding of the interrelations between political parties and the class forces they represent. These relations are not at all simple, uniform, or unvarying but extremely complicated, many-sided, and shifting. In the first place, it is impossible for any bourgeois party to present itself to the electorate as such. The capitalist exploiters constitute only a tiny fragment of the nation; their interests constantly conflict with those of the producing masses, generating class antagonisms at every step. They can conquer power and maintain it only through the exercise of fraud, trickery, and, when necessary, by main force. Their political representatives in a democratic state are therefore constrained to pass themselves off as servants of the people and to mask their real designs behind empty promises and deceitful phrases. The official actions of these agents negate their democratic pretensions time and again. Opportunism, demagogy, dupery, and betrayal are the hallmarks of every bourgeois party.

Since the masses sooner or later discover their betrayal and turn against the party they have placed in power, the ruling class must keep another political organization in reserve to throw into the breach. Hence the necessity for the two-party system. The Democratic and Republican Parties share the task of enforcing the domination of big capital over the people. From the social standpoint, the differences between them are negligible.

The apparent impartiality and independence of the twin parties and their leaders is an indispensable element in the mechanics of deception whereby the rich tyrannize over the lesser orders of the people. In affirming the classless character of the capitalist parties, Josephson shows himself to be no less enthralled by this fiction than the most ignorant worker. The worker, however, has had no opportunities to know better.

In the second place, no party can directly and immediately represent an entire class, however great a majority of suffrage it enjoys at any given moment. Intra-party controversies and splits, no less than inter-party conflicts, reflect the divergences between the component parts of a class as well as the opposing interests of different classes, which constituted the coalition parties of the bourgeoisie.

A new party, made up of the most conscious and advanced members of a class, frequently comes into violent collision with the more backward sections of the same class. This was true of the Republican Party throughout the Second American Revolution.

Thus Josephson’s contention that “the ruling party often vexed and disappointed the capitalists as in the impeachment action itself, in its ‘excesses’, or pursuit of its special ends”, does not at all demonstrate the supra-class position of the Radical Republicans. It goes to prove that they were more intransigent and clear-sighted defenders of Northern capitalism than many hesitant and conservative capitalists.

Finally, the independence of any party from the social forces it represents is always relative and often restricted within narrow limits. However long or short the tether, however tightly it was drawn at any given moment, the leadership of both parties was tied to the stake of the plutocracy. Whenever important individuals or tendencies began to assert themselves at the expense of the capitalist rulers or in opposition to their interests, counter-movements inevitably arose to bring them to heel, cast them out, or crush them. Josephson reports a hundred instances of this process in his book. Wherever the spoilsmen grabbed too much or too openly, they evoked Civil Service or reform movements, initiated or supported by those bourgeois groups demanding honest, cheap, or more efficient administration of their affairs.

The sovereignty of the Capitalists stands out in bold relief in many individual cases described by Josephson. When Johnson dared oppose the Radicals, he was fought, impeached, and then discarded. When his successor Grant endeavored to assert his independence of the Senatorial Cabal, he was quickly humbled and converted into a docile tool of the plutocracy. J.P. Morgan broke Cleveland’s resistance to his financial policies after months of struggle and bent the President to his will.

Even more instructive is the example of Altgeld, recently resurrected as a liberal hero. Those who recall his pardon of the Chicago Anarchists conveniently ignore the cause and outcome of his controversy with President Cleveland during the railroad strikes of 1894, led by Debs. The Governor of Illinois wanted to use the State Guard alone to break the strike; the President insisted on sending in Federal troops as well. Their quarrel amounted to a jurisdictional dispute as to which was to have the honor of suppressing the strike. Both state and federal troops were finally used. Thus the radical petty-bourgeois leader vied with the conservative commander of the big bourgeoisie in protecting the interests of the possessing classes against the demands of labor.

The Consolidation of the Two-Party System

After annihilating the slavocracy, the reigning representatives of the big bourgeoisie set about to reinforce their supremacy. While the masters of capital were concentrating the principal means of production in their hands and extending their domination over ever-larger sectors of the national economy, their political agents were seizing the controlling levers of the state apparatus in the towns, cities, states, and federal government. The simultaneous growth of monopolies in the fields of economics and politics was part and parcel of the same process of the consolidation of capitalist rule.

The two major parties became the political counterparts of the capitalist trusts. Functioning as the right and left arms of the big bourgeoisie, the Republican and Democratic Parties exercised a de facto monopoly over political life. The masses of the people were more and more excluded from direct participation and control over the administration of public affairs. The capitalist politicians did not attain this happy result at one stroke nor without violent struggle within the two parties and within the nation. Overriding all opposition, outwitting some, crushing others, bribing still a third, they succeeded in thoroughly domesticating both organizations until the crisis of 1896.

The two-party system of capitalist rule was the most characteristic product of the political reaction following the great upheaval of the Civil War. This mechanism enabled the plutocracy to maintain its power undisturbed during an epoch of relatively peaceful parliamentary struggle.

The managers of the two parties had two main functions to perform in defense of the bourgeois regime. First of all, they had to safeguard the bourgeois parties against the infiltration of dangerous influences emanating from the demands of the masses. In addition, they had to head off any independent mass movement which jeopardized the two-party system and therewith the domination of the plutocracy.

The monopoly of the two great political corporations was accompanied by the ruthless expropriation of political power from the lower classes, the strangling of their independent political enterprises, their more intensive exploitation in the interests of the commanding clique. This state of political affairs combined with the periodic economic crises generated the series of popular revolts culminating in the campaign of 1896. We can discern two dominant tendencies in the political turmoil of the times: on one side, the two major parties, despite their secondary differences, cooperating in promoting the ascendancy and interests of the big bourgeoisie; on the opposite side, various popular movements which welled forth from the lower classes in their attempts to reverse the process of capitalist consolidation and to assert their own demands in opposition.

Although these two tendencies were of unequal strength, corresponding to the disparities in the social weight and influence of the farmers and workers as against their oppressors, it was the struggles between these two camps, and not the secondary and largely sham battles between the two capitalist parties, that constitute the socially significant struggles of the epoch. Bourgeois historians, however, focus their spotlight upon the contests of the monopolist parties which crowd the foreground of the political arena, leaving obscure the popular protest movements which agitated in the background and emerged into national prominence only on critical occasions. Josephson has not freed himself from this preoccupation. While The Politicos presents an illuminating picture of the top side of American politics revolving around the inner life of the plutocratic parties and their struggles for hegemony, it systematically slights the underside of the political life of the same period.

Josephson devotes attention to the third party movements expressing the aspirations of the plebian orders and embodying their efforts to emancipate themselves from bourgeois tutelage, only as they affected, approach, or merge into the channels of the two-party system. He shows himself to be considerably more enslaved by bourgeois standards of political importance, and a far less independent, critical, and astute historian of post-Civil War political life than the evangelical liberal, V.L. Barrington, who, for all his deficiencies, is keenly conscious of major issues and alignments.

This is not an accidental error on Josephson’s part but an offshoot of his theoretical outlook. He draws the same fundamental conclusions from the political experiences of the post-war epoch as other bourgeois historians. American politics moves in a bipartisan orbit; third-party movements are short-lived aberrations from the norm, predestined to disappear or to be absorbed into new two-party alignments; state power oscillates between the Ins and Outs in a process as recurrent and inevitable as the tides.

Josephson even regards the two-party regime as “a distinct and enduring” contribution of American statecraft to “realistic social thought”, although the American bourgeoisie borrowed this system from the British ruling class, who fixed the pattern of parliamentary government for the rest of the Western World. Superficially considered, American politics since the Civil War tends to confirm these conclusions. Despite their promising beginnings, none of the third party movements developed into an independent and durable national organization, let alone succeeding in uncrowning the plutocracy; even the mighty Populist flood, with its millions of voters and followers, was sucked into the channels of the two-party system in 1896 where it ebbed away into nothingness after its defeat; the two-power system has remained intact and triumphant until today.

These third party movements were to be sure chiefly responsible for whatever political progress was accomplished during this period. Their militancy kept alive the spark of revolt against the existing order. They provided the experimental laboratories in which the creative social forces worked out their formulas of reform. These programs of reforms fertilized the otherwise barren soil which their activities furrowed. Some of these minor reforms even found partial fruition through the two major parties. Exerting pressure upon their left flanks, the third party movements pushed the monopolist parties forward step by step, exacting concessions from them. Nevertheless the fact remains that none of the third-party movements blossomed into a full-blown national party, on a par with the two big bourgeois organizations.

The situation appears in a different light, however, upon a critical examination of the causes and conditions of their failure.

First, the aims, programs, composition, and leadership of these movements were almost wholly middle-class in character. The heterogeneous nature of the middle-classes hindered them from welding together their own class forces in a permanent organization; their interests as small property-owners and commodity producers set them at odds with the industrial workers; a fundamental community of interests deterred them from conducting an intransigent or revolutionary struggle against their blood brothers, the big property owners.

Second, these petty-bourgeois protest movements lacked the stamina, solidity, and stability to weather boom periods. Blazing up during economic crisis, they died down during the subsequent upswing. The upper strata of the middle classes were satisfied with higher prices or petty reforms; the masses sank back into political passivity.

Third, the history of the third party movements is a sorry record of the betrayal of the plebian masses by their leadership. This leadership was largely made up of careerist politicians or representatives of the upper middle-classes, who were usually ready to make unprincipled deals with the managers of the two big parties; to forsake their principles and the interests of their followers for a few formal concessions or promises; to quit the building of an independent movement for the sake of a cheap and easy accession to office. An almost comic example of this was the fiasco of the Liberal Reform movement of 1872, which, originating in revulsion against the degeneracy of the Republican Stalwarts, ended by nominating Horace Greeley as a joint candidate with the Democrats in a presidential convention manipulated by wire-pulling, ruled by secret diplomacy, and consummated in an unprincipled deal that totally demoralized the movement and disheartened its sympathizers. Even more striking was the decision of the Populist Party in 1896 to abandon its identity and support Bryan, the Democratic nominee. Finally, the mesmerizing effect of the two-party system and the activities of the capitalist politicians must be taken into account. They threw their full weight against every sign of independent political action reflecting mass discontent, crushing wherever they could not capture or head off the nascent movement of rebellion.

The sole social force capable of forging and leading a strong, stable, and independent movement against the plutocracy, the proletariat, was too immature to undertake that task. As a rule, the industrial workers remained politically subservient to bourgeois interests and influence; they limited their field of struggle to the economic arena; their trade-union leaders adhered to the policy of begging favors from the two parties as the price of their allegiance; the left wing labor and socialist parties remained insignificant sects.

The two-party system was therefore perfected under certain specific social, economic, and political conditions and its perpetuation depends upon the continuation of these conditions.

Prospects of the Two-Party System

The two-party regime, however, is no more eternal than the bourgeois democracy it upholds. Its stability is guaranteed only by the relative stability of the social relations within the nation.

The two-party system consolidated itself when American capitalism was in the ascendant; when the masters of capital sat securely in the saddle; when the proletariat was weak, disorganized, divided, and unconscious; when the direction of political mass movements fell to the middle-classes. There was plenty of room for class accommodation; ample means for concessions; opportunities and necessities for class reconciliation. Consequently, the political equilibrium was each time restored after it had been upset by severe class conflicts.

These circumstances either no longer prevail or are tending to disappear. American capitalism is on the downgrade; the proletariat is powerful, well-organized, militant; the capitalists are in a quandary; the middle classes are nervous and restless. All the antagonisms that slumber in the depths of American society are being awakened and fanned to a flame by the chronic social crisis. The forces formerly confined within the framework of the two-party system are pounding against its walls, cracking it in a hundred places. The sharpening class conflicts can no longer be regulated inside the old political setup. The vanguard of the contending forces are straining to break the bonds which tie them to the old parties and to forge new instruments of struggle better adapted to the new situation.

While the trend toward new forms of political action and organization are common to all classes, the movement most fraught with significance for the future is the manifest urge of the organized labor to seek the road of independent political action. Skeptics, conservative-minded pedants, Stalinists, interested trade-union bureaucrats, and all those under the spell of traditional bourgeois prejudices point to the futility of third party movements in the past to discourage the workers from taking this new road and to keep them in the old ruts. Their historical arguments are based entirely upon conditions of a bygone day.

Viewed on an historical scale, American society and therewith American politics is today in a transitional period, emerging out of the old order into a pre-revolutionary crisis. This new period has its historical parallel, not in the post-revolutionary epoch following the Civil War, but in the period preceding it. “The irrepressible conflict” between the reactionary slaveholders and the progressive bourgeoisie has its contemporary analogy in the irrepressible conflict between the capitalist and working classes.

The class conflicts which then shook the social foundations of the Republic shattered all existing political formations. The Whigs and Democrats, which had, like the Republican and Democratic Parties, monopolized the political stage for decades in the service of the slave power, were pulverized by the blows delivered from within and from without by the contending forces. The turbulent times gave birth to various kinds of intermediate parties and movements: Free-soil, Know-Nothing, Liberty movements. The creators of the Republican Party collected the viable, progressive, and radical forces out of these new mass movements and out of the old parties to form a new national organization.

As the Abolitionists knew and declared, the Republican Party was not revolutionary in its principles, program, or leadership. It was a bourgeois reformist party aiming to alter the existing political system for the benefit of the big and little bourgeoisie, not to overthrow it. This did not prevent the slaveholders from regarding it as a revolutionary menace to their rule. From 1854 to 1860 the political atmosphere within the United States became totally transformed by the deepening social crisis. Six years after the launching of the Republican Party came its formal assumption of power, the rebellion of the slaveholders, civil war, and revolution. All this occurred as the result of objective social conditions, regardless of the will of the majority of the participants and contrary to their plans and intentions.

The national and international conditions of the class struggle are too radically different today for the forthcoming period to reproduce the pattern of pre-civil war days in any slavish manner. It is certain, however, that its revolutionary character and tendencies are considerably closer to the present situation and problems confronting the American people than are the conditions and concepts stemming from the post-Civil War era of capitalist consolidation and reaction.

Matthew Josephson and his school operate almost exclusively with ideas derived from the conditions of the post-revolutionary period and tacitly based upon a continuation of them. Their minds and writings are permeated with the same spirit of adaptation to the reigning order as their politics. A resurgent labor movement struggling to free itself from capitalist control must first cast off the obsolete prejudices inherited from its past enslavement. For a thoroughgoing critical revision of such antiquated ideas, the advanced intellectual representatives of labor among the rising generation will have to look elsewhere than in the pages of The Politicos.

The New International began as the theoretical organ of the Communist League of America, formed in 1928 by supporters of The International Left Opposition in the Communist Party. The CLA merged with the American Workers Party led by AJ Muste to form the Workers Party of the U.S. in Dec 1935 before intervening in the Socialist Party, at which time this magazine was suspended. After leaving the SP, the main Trotskyist forces formed the Socialist Workers Party in 1938 and resumed publication. In the split of 1940, the State Capitalist/ Bureaucratic Collectivist faction left the Party and held on to the magazine; the SWP then produced ‘The Fourth International’ as their organ of theory.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/ni/vol04/no09/v04n09-w24-sep-1938-new-int.pdf