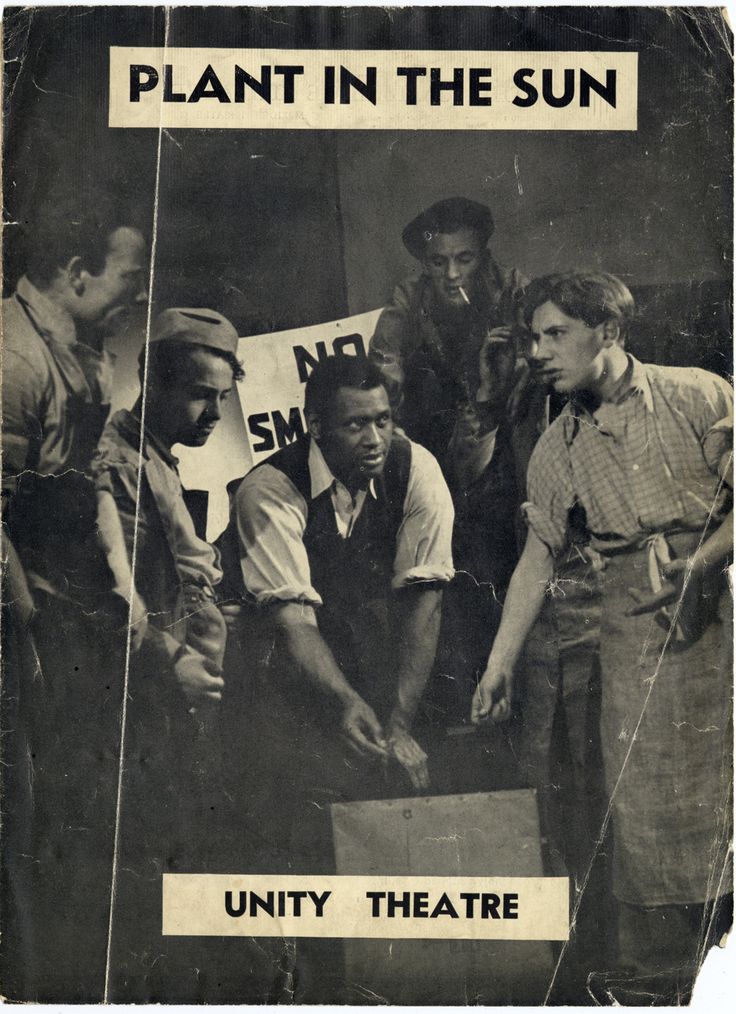

A milestone in Robeson’s increasing political commitment. While in London, where he was a popular film and stage star, he leaves the West End to join the new Unity Theatre, emerging from the Workers’ Theatre Movement, to put on a free production of ‘Plant in the Sun.’

‘Paul Robeson Joins Labor Theatre’ interview with Philip Bolsover from the Daily Worker. Vol. 14 No. 264. November 4, 1937.

Famed Singer Leaves West End Stage for Unity Theatre

“When I sing ‘Let My People Go,'” said Paul Robeson slowly, feeling for words, seeking expression to convey just the emphasis he needed, “I want it in the future to mean more than it has meant before.

“It must express the need for freedom not only of my own race. That’s only part of a bigger thing. But of all the working-class–here, in America, all over. I was born of them. They are my people. They will know what I mean.

“When I step on to a stage in the future,” Paul Robeson said, leaning forward in his chair, “I go on as a representative of the I working-class. I work with the consciousness of that in my mind. I share the richness they can bring to art. I approach the stage from that angle.

“You see,” he said, “this isn’t a bolt out of the Blue. Not a case of a guy suddenly sitting down and deciding that he wants to join a workers’ theatre. It began when I was a kid, a working-class kid living in that shack. It went on from that beginning.

“Films,” he added, “films eventually brought the whole thing to a head.

“I shan’t do any more films after the two that are being finished now. Not unless I can get a cast-iron story–the kind that I can’t be twisted in the making. There’s room for short independent films. I might try to do those. But for the rest, I’ll just wait until the right story comes along, either here or abroad.

“I thought I could do something for the Negro race on the films; show the truth about them–and about other people too. I used to do my part and go away feeling satisfied. Thought everything was O.K. Well, it wasn’t. Things were twisted and changed distorted. They didn’t mean the same. That made me think things out. It made me more conscious politically.

“One man can’t face the film companies. They represent about the biggest aggregate of finance-capital in the world–that’s why they make their films that way. So no more films for me.

Sympathy With Audiences

“Joining Unity Theatre,” said Robeson, “means Identifying myself with the working-class. And it gives me the chance to act in plays that say something I want to say about things that must be emphasized.

“I like singing for those audiences,” he said reminiscently. “There is sympathy between us. I sing better for them. I shall like acting for them.

“I sang in drawing-rooms once, but that was different. Like being on show all the time. We didn’t get on well.

“If I go into an expensive restaurant,” said Robeson, suddenly taking a new angle, “I see people stiffen and sit up. They say: ‘What’s that colored guy doing in here?’

“They’d like to throw me out,” he said, simply, “but they think I’d

make trouble. I should.

“But look what happens when I go into a provincial town. Drivers get off their trucks to shake hands. Guys working on buildings come and have a word. ‘Hullo, Paul,’ they shout.

“I got a record of yours,’ they say.”

He grinned and gave a deep chuckle.

“I get on fine with those fellows. We know each other. Those are the people I come from. And they understand what I sing.

“I’ve managed to gain some success,” said Paul Robeson, “but there are thousands who haven’t had the chance. It’s not enough for one to be able to do it; I want everyone to have the chance.

“The way things are it seems to me that from the artistic point of view there’s an immense waste of talent a waste of people who are not allowed to develop and use all that’s in them. And from every point of view there is a loss of human dignity and hope and happiness.

“So I’m joining a working-class theatre.”

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/per_daily-worker_daily-worker_1937-11-04_14_264/per_daily-worker_daily-worker_1937-11-04_14_264.pdf