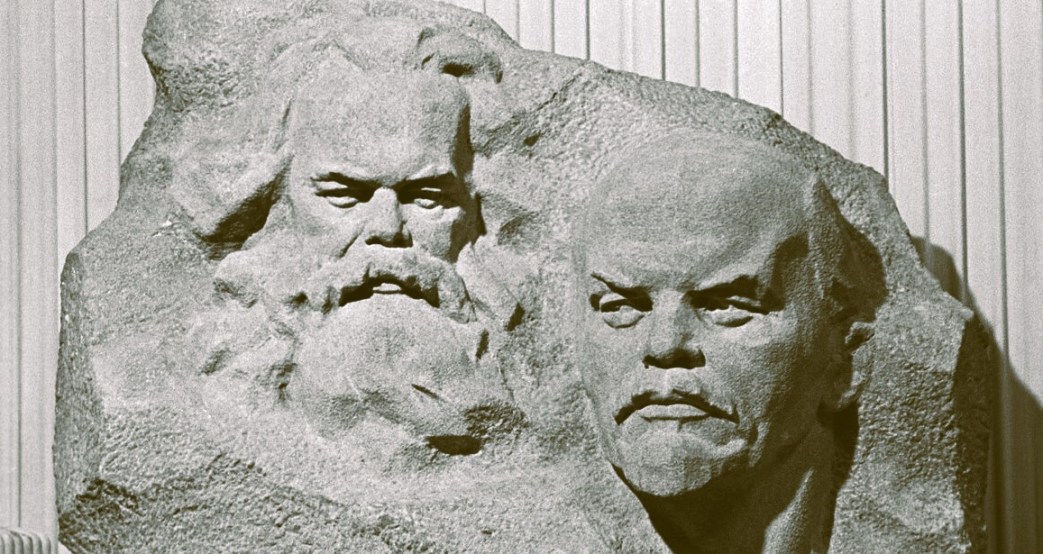

Lenin’s preface to the letters of Marx to Kugelmann, many of which are on the Paris Commune, also serves as a polemic against Plekhanov’s criticisms of the Moscow Insurrection of 1905 over the practicability of ‘storming heaven.’

‘Preface to the Russian Translation of Karl Marx’s Letters to Dr. Kugelmann’ (1907) by V.I. Lenin from Selected Works, Volume 11. International Publishers, New York. 1937.

Our aim in issuing as a separate pamphlet the full collection of Marx’s letters to Kugelmann published in the German Social-Democratic weekly, Neue Zeit, is to acquaint the Russian public more closely with Marx and Marxism. As was to be expected, a good deal of space in Marx’s correspondence is devoted to personal matters. For the biographer, this is exceedingly valuable material. But for the broad public in general, and for the Russian working class in particular, those passages in the letters which contain theoretical and political material are infinitely more important. It is particularly instructive for us, in the revolutionary period we are now passing through, carefully to study this material, which reveals Marx as a man who directly responded to all questions of the labour movement and world politics. The editors of the Neue Zeit were quite right when they remarked that “we are elevated by an acquaintance with the personality of men whose thoughts and wills took shape under conditions of great upheavals.” Such an acquaintance is doubly necessary to the Russian Socialist in 1907, for it provides a wealth of very valuable indications concerning the direct tasks confronting the Socialists in every revolution passed through by his country. Russia is passing through a “great upheaval” at this very moment. Marx’s policy in the comparatively stormy *sixties should very often serve as a direct model for the policy of the Social-Democrat in the present Russian revolution.

We shall therefore only very briefly note the passages in Marx’s correspondence which are of particular importance from the theoretical standpoint, and shall deal in greater detail with his revolutionary policy as a representative of the proletariat.

Of outstanding interest for a fuller and profounder understanding of Marxism is the letter of July 11, 1868.1 In the form of polemical remarks against the vulgar economists, Marx in this letter very clearly expounds his conception of what is called the “labour” theory of value. Those very objections to Marx’s theory of value which naturally arise in the minds of the least trained readers of Capital and which for this reason are most eagerly seized upon by the common or garden representatives of “professorial” bourgeois “science,” are here analysed by Marx briefly, simply and with remarkable lucidity. Marx here shows the road he took and the road: that should be taken to elucidate the law of value. He teaches us his method, using the most common objections as illustrations, He makes clear the connection between such a purely (it would seem) theoretical and abstract question as the theory of value and “the interests of the ruling classes,” which are “to perpetuate confusion.” It is only to be hoped that everyone who begins to study Marx and to read Capital will read and re-read this letter when studying the first and most difficult chapters of Capital.

Other very interesting passages in the letters from the theoretical standpoint are those in which Marx passes judgment on diverse writers, When you read these opinions of Marx—vividly written, full of passion and revealing a profound interest in all the great ideological trends and their analysis—you feel that you are listening to the words of a great thinker. Apart from the remarks on Dietzgen made in passing, the comments on the Proudhonists deserve the particular attention of the reader.2 The “brilliant” young bourgeois intellectuals who throw themselves “among the proletariat” at times of social upheaval and who are incapable of acquiring the standpoint of the working class or of carrying on persistent and serious work among the “rank and file” of the proletarian organisations are depicted by a few strokes with remarkable vividness.

Take the comment on Dithring,3 which, as it were, anticipates the contents of the famous Anti-Duhring written by Engels (in conjunction with Marx) nine years later. There is a Russian translation of this book by Zederbaum which is unfortunately guilty both of omissions and of mistakes and is simply a bad translation, Here, too, we have the comment on Thunen, which likewise touches on Ricardo’s theory of rent. Marx had already, in 1868, emphatically rejected “Ricardo’s mistakes,” which he finally refuted in Volume III of Capital, published in 1894, but which to this very day are repeated by the revisionists—from our ultra-bourgeois and even “Black Hundred” Mr. Bulgakov to the “almost orthodox” Maslov.

Interesting also is the comment on Buchner, with the judgment of vulgar materialism and the “superficial nonsense” copied from Lange (the usual source of “professorial” bourgeois philosophy!).4

Let us pass to Marx’s revolutionary policy. A certain petty bourgeois conception of Marxism is surprisingly current among Social-Democrats in Russia according to which a revolutionary period, with its specific forms of struggle and its special proletarian tasks, is almost an anomaly, while a “constitution” and an “extreme opposition” are the rule. In no other country in the world at this moment is there such a profound revolutionary crisis as in Russia—and in no other country are there “Marxists” (belittling and vulgarising Marxism) who take up such a sceptical and philistine attitude towards the revolution. From the fact that the content of the revolution is bourgeois the shallow conclusion is drawn in our country that the bourgeoisie is the driving force of the revolution, that the tasks of the proletariat in this revolution are of an auxiliary and not independent character and that proletarian leadership of the revolution is impossible!

How excellently Marx, in his letters to Kugelmann, exposes this shallow interpretation of Marxism! Here is a letter dated April 6, 1866. At that time Marx had finished his principal work. He had already given his final judgment on the German Revolution of 1848 fourteen years before this letter was written. He had himself, in 1850, renounced his socialistic illusions that a Socialist revolution was impending in 1848. And in 1866, when only just beginning to observe the growth of new political crises, he writes:

“Will our philistines [he is referring to the German bourgeois liberals] at last realise that without a revolution which removes the Habsburgs and Hohenzollerns…there must finally come another Thirty Years’ War…!”5

Not a shadow of illusion here that the impending revolution (it took place from above and not from below as Marx had expected) would remove the bourgeoisie and capitalism, but a most clear and precise statement that it would remove only the Prussian and Austrian monarchies. And what faith in this bourgeois revolution! What revolutionary passion of a proletarian fighter who realises the vast significance of a bourgeois revolution for the advance of the Socialist movement!

Three years Jater, on the eve of the downfall of the Napoleonic Empire in France, drawing attention to “a very interesting” social movement, Marx says in a positive outburst of enthusiasm that

“the Parisians are making a regular study of their recent revolutionary past, in order to prepare themselves for the business of the impending new revolution.”6

And describing the struggle of classes revealed in this study of the past, Marx concludes:

“And so the whole historic witches’ cauldron is bubbling. When shall we [in Germany] be so far!”7

Such is the lesson that should be learned from Marx by the Russian intellectual Marxists, who are debilitated by scepticism, dulled by pedantry, have a penchant for penitent speeches, rapidly tire of revolution, and who yearn, as for a holiday, for the interment of the revolution and its replacement by constitutional prose. They should learn from the theoretician and leader of the proletarians faith in the revolution, the ability to call on the working class to uphold its immediate revolutionary aims to the last, and the firmness of spirit which admits of no faint-hearted whimpering after temporary setbacks of the revolution.

The pedants of Marxism think that this is all ethical twaddle, romanticism and lack of a sense of reality! No, gentlemen, this is the combination of revolutionary theory and revolutionary policy without which Marxism becomes Brentanoism, Struvism and Sombartism. The Marxian doctrine has bound the theory and practice of the class struggle into one inseparable whole, And whoever distorts a theory which soberly presents the objective situation into a justification of the existing order and goes to the length of striving to adapt himself as quickly as possible to every temporary decline in the revolution, to discard “revolutionary illusions” as quickly as possible and to turn to “realistic” tinkering, is no Marxist.

During the most peaceful, seemingly “idyllic,” as Marx expressed it, and “wretchedly stagnant” (as the Neue Zeit put it) times, Marx was able to sense the approach of revolution and to rouse the proletariat to the consciousness of its advanced revolutionary ‘tasks. Our Russian intellectuals, who, like philistines, vulgarise Marx, teach the proletariat in most revolutionary times a policy of passivity, of submissively “drifting with the stream,” of timidly supporting the most unstable elements of the fashionable liberal party!

Marx’s appreciation of the Commune crowns the letters. to Kugelmann. And this appreciation is particularly valuable when compared with the methods of Russian Social-Democrats of the Right wing. Plekhanov, who after December 1905 faint-heartedly exclaimed: “They should not have resorted to arms,” had the modesty to compare himself to Marx. Marx, he implied, also put the brakes on the revolution in 1870.

Yes, Marx also put the brakes on the revolution. But see what a gulf yawns between Plekhanov and Marx in this comparison made by Plekhanov himself!

In November 1905, a month before the first revolutionary wave had reached its apex, Plekhanov, far from emphatically warning the proletariat, definitely said that it was necessary “to learn to use arms and to arm.” Yet, when the struggle flared up a month later, Plekhanov, without making the slightest attempt to analyse its significance, its role in the general course of events and its connection with previous forms of struggle, hastened to play the part of a penitent intellectual and exclaimed: “They should not have resorted to arms.”

In September 1870, six months before the Commune, Marx definitely warned the French workers. Insurrection would be a desperate folly, he said in the well-known Address of the International. He revealed in advance the nationalistic illusions concerning the possibility of a movement in the spirit of 1792. He was able to say, not after the event, but many months before: “Don’t resort to arms.”

And how did he behave when this hopeless cause, as he himself had declared it to be in September, began to take practical shape in March 1871? Did he use it (as Plekhanov did the December events) to “take a dig” at his enemies, the Proudhonists and Blanquists who led the Commune? Did he begin to scold like a schoolmistress, and say: “I told you so, I warned you; this is what comes of your romanticism, your revolutionary ravings”? Did he preach to the Communards, as Plekhanov did to the December fighters, the sermon of the smug philistine: “You should not have resorted to arms”?

No, On April 12, 1871, Marx writes an enthusiastic letter to Kugelmann—a letter which we would like to see hung in the home of every Russian Social-Democrat and of every literate Russian worker.

In September 1870 Marx called the insurrection a desperate folly; but in April 1871, when he saw the mass movement of the people, he observed it with the keen attention of a participant in great events that mark a step forward in the historic revolutionary movement.

This is an attempt, he says, to smash the bureaucratic military machine and not simply to transfer it from one hand to another. And he sings a veritable hosanna to the “heroic” Paris workers led by the Proudhonists and Blanquists.

“What elasticity,” he writes, “what historical initiative, what a capacity for sacrifice in these Parisians! … History has no like example of a like greatness.”8

The historical initiative of the masses is what Marx prizes above everything else. Oh, if only our Russian Social-Democrats would learn from Marx how to appreciate the historical initiative of the Russian workers and peasants in October and December 1905!

The homage paid to the historical initiative of the masses by a profound thinker, who foresaw failure six months before—and the lifeless, soulless, pedantic: “They should not have resorted to arms”! Are these not as far apart as heaven and earth?

And like a participant in the mass struggle, to which he reacted with al! his characteristic ardour and passion, Marx, living in exile in London, sets to work to criticise the immediate steps of the “foolishly brave” Parisians who were ready to “storm heaven.”

Oh, how our present “realist” wiseacres among the Marxists who are deriding revolutionary romanticism in Russia in 1906-07 would have sneered at Marx at the time! How people would have scoffed at a materialist, an economist, an enemy of utopias, who pays homage to an “attempt” to storm heaven! What tears, condescending smiles or commiseration these ‘men in mufflers” would have bestowed upon him for his rebel tendencies, utopianism, etc., etc., and for his appreciation of a heaven-storming movement!

But Marx was not inspired with the wisdom of gudgeons who are afraid to discuss the technique of the higher forms of revolutionary struggle. He discusses precisely the technical problems of the insurrection, Defence or attack?—he asks, as if the military operations were taking place just outside London. And he decides that it must certainly be attack: “They should have marched at once on Versailles…”

This was written in April 1871, a few weeks before the great and bloody May…

“They should have marched at once on Versailles”—should the insurgents who had begun the “desperate folly” (September 1870) of storming heaven,

“They should not have resorted to arms” in December 1905 in order to oppose by force the first attempts to withdraw the liberties that had been won…

Yes, Plekhanov had good reason to compare himself to Marx!

“Second mistake,” Marx says, continuing his technical criticism: “The Central Committee (the military command—note this—the reference is to the Central Committee of the National Guard) surrendered its power too soon…”

Marx knew how to warn the leaders against a premature rising. But his attitude towards the proletariat which was storming heaven was that of a practical adviser, of a participant in the struggle of the masses, who were raising the whole movement to a higher level in spite of the false theories and mistakes of Blanqui and Proudhon.

“However that may be,” he writes, “the present rising in Paris—even if it be crushed by the wolves, swine and vile curs of the old society—is the most glorious deed of our Party since the June insurrection.”

And Marx, without concealing from the proletariat a single mistake of the Commune, dedicated to this deed a work which to this very day serves as the best guide in the fight for “heaven” and as a frightful bugbear to the liberal and radical “swine.”

Plekhanov dedicated to the December events a “work” which has almost become the bible of the Constitutional-Democrats.

Yes, Plekhanov had good reason to compare himself to Marx.

Kugelmann apparently replied to Marx expressing certain doubts, referring to the hopelessness of the matter and preferring realism to romanticism—at any rate, he compared the Commune, an insurrection, to the peaceful demonstration in Paris on June 13, 1849.

Marx immediately (April 17, 1871) reads Kugelmann a severe lecture.

“World history,” he writes, “would indeed be very easy to make, if the struggle were taken up only on condition of infallibly favourable chances.”9

In September 1870 Marx called the insurrection a desperate folly. But when the masses rose Marx wanted to march with them, to learn with them in the process of the struggle, and not to read them bureaucratic admonitions. He realises that to attempt in advance to calculate the chances with complete accuracy would be quackery or hopeless pedantry. What he values above everything else is that the working class heroically and self-sacrificingly takes the initiative in making world history. Marx regarded world history from the standpoint of those who make it without being in a position to calculate the chances infallibly beforehand, and not from the standpoint of an intellectual philistine who moralises: “It was easy to foresee…they should not have resorted to…”

Marx was also able to appreciate that there are moments in history when the desperate struggle of the masses even for a hopeless cause is essential for the further schooling of these masses and their training for the next struggle.

Such a statement of the question is quite incomprehensible and even alien in principle to our present-day quasi-Marxists, who love to take the name of Marx in vain, to borrow only his estimate of the past, and not his ability to make the future. Plekhanov did not even think of it when he set out after December 1905 “to put the brakes on.”

But it is precisely this question that Marx raises, without in the least forgetting that he himself in September 1870 regarded insurrection as a desperate folly.

“…The bourgeois canaille of Versailles,” he writes, “…presented the Parisians with the alternative of taking up the fight or succumbing without a struggle. In the latter case, the demoralisation of the working class would have been a far greater misfortune than the fall of any number of leaders.”

And with this we shall conclude our brief review of the lessons in a policy worthy of the proletariat which Marx teaches in his letters to Kugelmann.

The working class of Russia has already proved once and will prove again more than once that it is capable of “storming heaven.”

February 18, 1907

1. Cf. Karl Marx, Letters to Dr. Kugelmann, Eng. ed., 1934, pp. 73 et seq. Trans.

2. Ibid., pp. 39-40. Trans.

3. Ibid., p. 63. Trans.

4. Ibid., p. 80. Trans.

5. Ibid., p. 35. Trans.

6. Ibid., p. 88. Trans.

7. Ibid., p. 89. Trans,

8. Ibid., p. 123. Trans.

9. Ibid., p. 125. Trans.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/selected-works-vol.-11/Selected%20Works%20-%20Vol.%2011.pdf