A comrade from Holland, Michigan–a center of furniture making–describes the changes to woodworking where, like so many other industries, skilled artisans were replaced by machines and ‘unskilled’ labor.

‘The Woodworking Industry’ by A Machine Woodworker from The Weekly People. Vol. 13 No. 28. October 10, 1903.

Long years before the first rude tools and weapons of stone and iron were fashioned the savage fashioned tools of wood to work with and built the first rude dwellings and made wooden vessels and utensils for the shelter and comfort of savage humanity. The club and the bow and arrow, weapons for hunt and war, the digging stick and the wood drill are amongst man’s earliest efforts at tool making and progress.

Experience soon taught humanity that stone, iron and steel were better adapted for use as tools. Wood was then relegated to a secondary position, and instead of being primarily the object with which commodities were made, it became the raw material from which commodities are made. From being the object to effect an end (a tool), it became the end itself (a commodity). Mankind, no longer workers with wood, became workers in wood. From this point the woodworking, as a trade, separated itself from the rest of production.

It is not the object of this article to trace each successive step dating from that remote period to the present time, but to present a few important changes or modifications, amounting almost to revolutions occurring in this industry, that should be known, in order that the subject may be fully understood by the reader.

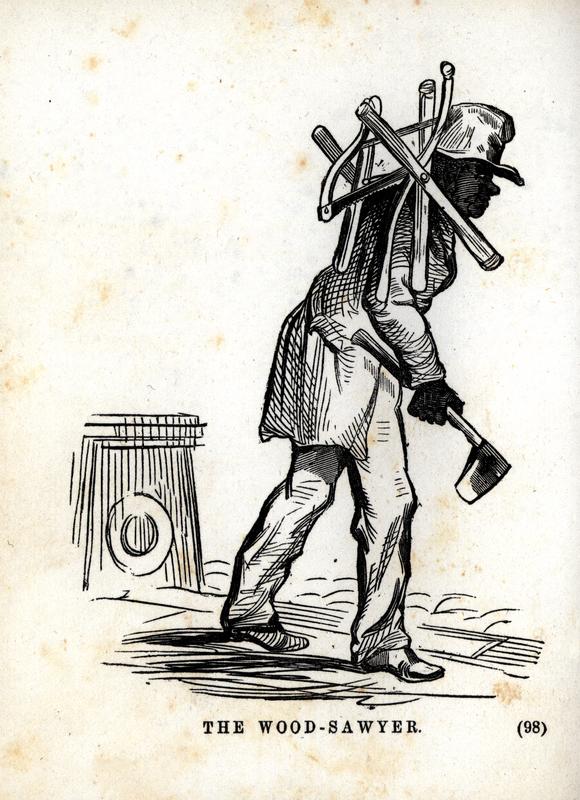

The ancient woodworker chopped down the tree, squared it with an adz, ripped off a board, with the whip saw put it into different lengths, and with planers and chisels planed and grooved the pieces, preparatory to joining them.

Then, finally and finely, he put all these together into the desired form–a table or a drawer–painting and varnishing the same. When finished, the article thus created stood complete, the product of one man’s cunning, fashioned in all the beauty his imagination could conceive, and containing all the durability his skill and strength could give.

He could look at this article and say, “It is all mine. I, and I alone, created it; and to me alone it belongs.”

But with evolution there came the grouping of humanity into hamlets and towns. Bigger undertakings required cooperation amongst craftsmen. Special skill in some details brought about a diversion of labor. Theoretically, each of the craftsmen could perform all the branches of his craft. Practically, the different branches of woodworking appeared, and from this point onward the breach widened, separating into different trade what were before but differing details of the same work. Then arose housebuilders, cabinetmakers, choppers, hewers, pit sawyers, carvers, wagon and basketmakers.

Simultaneously with this stage of development, production leaped forward with a bound. But a change in the craftsmen is noticeable. A part of his kit of tools is no longer useful to him. Two pit sawyers may own a whip saw, but the cabinetmaker no longer does so. He is now divorced from it. No longer an independent producer, he becomes one of a series of interdependent producers of the parts of an article.

Despite this, the cabinetmaker is comparatively able to secure the full products of his labor. The tools he possesses are few and simple. Their possession enables him to compete with every other craftsman of like skill and ability, and to secure the approximate value of his labor. A new factor now enters the field: machinery, i.e., the complex tool driven by motive power.

The first power saw mill was built in 1337 at Sugsburg. In 1625 the Dutch built the first saw mill in America, on Manhattan Island. In 1663 a Hollander erected a mill near London, but the pit sawyers, seeing their danger, burned it down.

The skillful pit sawyers were the first to go before the upright saw. This saw, with the aid of two men, performed the work of a dozen sawyers. At least ten of the dozen were now divorced from the tools of their trade.

The upright saw gave place to the circular; the circular, in turn, gave way to the mammoth band saw, whose simple machinery, operated by one skilled mechanic and 100 laborers, can perform the labor of 10,000 ancient hand sawyers.

The whip saw was not alone in being displaced. The plane, the chisel, the brace and bit had to give way to the rotary planer, the mortising and boring machine. Even the hand sand blocks had to make way for the machine sander, weighing several tons and having three cylinders covered with different sizes of sandpaper, from the very coarsest to the very finest.

With the change from the hand tool to the machine, there has also gone a change from the individual hand worker to the cooperative machine worker-a change that has wrought a greater change in the position of the workers themselves.

The old-time craftsman would build an article from top to bottom. He had the tools wherewith to do; and, when he was finished, the article, or its equivalent, was his. If he hired out he received all that he could earn when laboring independently. His employer, in that event, was usually another craftsman working at the bench himself, with a larger job on hand than he could handle singly. If the employee didn’t like the job or boss he could quit, set up for himself and compete with his former employer. He owned the tools of production necessary to enable him to do so. The modern worker may be a stock sawyer, a planer, shaper, sticker, or sanderman, a cabinetmaker, a varnisher, painter, carpenter, wagonmaker, or a part or portion of any of the above (for the subdivisions are infinitesimal), but he will not be capable of working alone. If he would produce he must cooperate with his fellow-workingmen. The woodworkers have ceased to be the independent workingmen of former years and are now the dependent hundredth part of a woodworker, bound to labor together with the remaining ninety-nine hundredths.

We woodworkers can no longer quit, as we no longer own the tools and the factories. We can no longer compete, as a few men (the employers or capitalists) have possession of both tools and plants. We are forced to operate the capitalist’s machinery in cooperation with one another. They will only give us the opportunity to do so on condition that we give them ALL OF OUR OWN PRODUCTS over and above what is necessary to sustain our life and reproduce our species.

We no longer have any skill or trade. Our trade has been divorced from us by the division of labor and the simplicity of mechanical invention, which enables machine boys of 12, 13 and 14 years of age, who can take our places and do our work. All, combined with ever-decreasing piece prices, covering ever-larger quantities of material, forces us to greater speed.

In the machine room, crowded together around machines speeded up to breakneck speed, at the risk of fingers, hands, and even lives, inhaling the dust that inadequate blowers fail to carry away, the machine woodworker labors for a mere pittance. Or else it’s the cabinet room, which, with its child labor and piece work, force the workers to the verge of nervous prostration to secure a livelihood. Or else it’s the finishing room, with its blended perfumes, not of musk or attar of roses, but the deadly odors of turpentine, varnish, naphtha, boiled oil and wood alcohol, where the finisher engages in piece work with hunger as the pacemaker. Or, finally, it’s the outside carpenter, who labors a few months a year, insecurely living a hand-to-mouth existence, and speculating on what would have happened had the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters lost its fight with the Brotherhood of Carpenters.

All these facts combined spread the way that lead to an early grave for the woodworkers. The question of race suicide for us is solved. Gray hairs are almost unknown amongst us. The old-young boy is becoming the type.

Women and girls are also taking the places of the former aristocrats of labor. The Spindle Morris machine, pressed work, and, finally, clay carvings made by women and children, have forced the hand carvers, the aristocrats of our “trade,” into the rear ranks.

Such is the true picture of the woodworker of today. It is devoid of economic triumphs. With the Amalgamated and the Brotherhood and the International Woodworkers after each other’s scalp, thereby playing into the employer’s hands, the woodworkers today stand a slave who cannot be made free but through the ownership of his chains (the machine). To him and to all such as him the Socialist Labor Party extends a hand, saying, “Come, brothers, with our arm (united action) and hammer (the ballot) WE WILL STRIKE OFF OUR SHACKLES BY TAKING POSSESSION OF ALL THE MACHINERY OF PRODUCTION AND DISTRIBUTION, THUS ENDING FOR ALL TIME THE EXPLOITATION OF THE WORKERS BY THE CAPITALIST CLASS, AND ALL CLASS RULE.”

A Machine Woodworker. Holland, Mich.

New York Labor News Company was the publishing house of the Socialist Labor Party and their paper The People. The People was the official paper of the Socialist Labor Party of America (SLP), established in New York City in 1891 as a weekly. The New York SLP, and The People, were dominated Daniel De Leon and his supporters, the dominant ideological leader of the SLP from the 1890s until the time of his death. The People became a daily in 1900. It’s first editor was the French socialist Lucien Sanial who was quickly replaced by De Leon who held the position until his death in 1914. Morris Hillquit and Henry Slobodin, future leaders of the Socialist Party of America were writers before their split from the SLP in 1899. For a while there were two SLPs and two Peoples, requiring a legal case to determine ownership. Eventual the anti-De Leonist produced what would become the New York Call and became the Social Democratic, later Socialist, Party. The De Leonist The People continued publishing until 2008.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-slp/031010-weeklypeople-v13n28.pdf