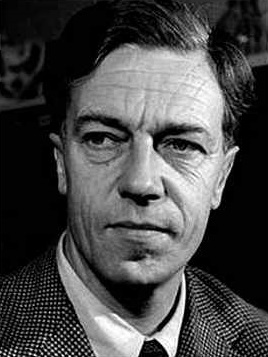

Cecil Day Lewis, the father of the actor then in his Communist years, evaluates the work of William Butler Yeats on his death in 1939. Day Lewis would continue writing and lecturing about Years for the rest of his literary career.

‘W.B. Yeats’ by Cecil Day Lewis from New Masses. Vol. 30 No. 11. March 7, 1939.

An appraisal by C. Day Lewis of the famous Irish poet’s achievement as artist and citizen. Yeats’ conflict between the real and the romantic.

YEATS, more than any other, is a poet of whom I find it difficult to write objectively. From the day when, a boy of sixteen, sitting in a vicarage garden in the middle of the Nottingham coal fields, I first began reading his poems, he was always for me the most admired of living poets, the one whose mantle–and with what conscious arrogance he wore it!–I could have wished to inherit. But even then, while I was first reading his earlier poems, he had discarded the “Celtic Twilight” manner that was so fatally easy to imitate, discarded the singing robes of which he wrote:

I made my song a coat

Covered with embroideries

Out of old mythologies

From heel to throat;

But the fools caught it,

Wore it in the world’s eyes

As though they’d wrought it…

and, deciding that “there’s more enterprise/In walking naked,” had come out in the inimitable austerity of his later work. This change was not really, of course, due to a fit of pique against the plagiarists. Nor was it, as many critics seem to imply, a lightning-change: we can see traces of the new manner in The Wind among the Reeds (1899), and vestiges as late as From the Green Helmet (1912). Nor yet, I think, is it accurate to attribute the transition entirely to an awakening interest in politics.

The 1917 [sic] rebellion, which called out his finest political verse, found him already settled down to the new poetic idiom. As to earlier events, he tells us in a note to Responsibilities, written in 1914, that “In the thirty years or so during which I have been reading Irish newspapers, three public controversies have stirred my imagination. The first was the Parnell controversy…And another was the dispute over The Playboy…The third prepared for the Corporation’s refusal of a building for Sir Hugh Lane’s famous collection of pictures.” He adds, “These controversies, political, literary, and artistic, have showed that neither religion nor politics can of itself create minds with enough receptivity to become wise, or just and generous enough to make a nation.”

Yeats’ contributions to the political life of Ireland, like his occasional incursions into practical politics, were those of a writer, not of a politician. His work for the National Theater is well known and honored now even in Ireland, though at the time it plunged him into a welter of violence, recriminations, and intrigues an atmosphere at first by no means distasteful to his pugnacious spirit. He is, throughout, the aristocratic poet who feels a passionate love for the Cause but also a certain contempt for the human instruments with which he has to work. It was this contempt which led him so quickly into disillusionment: he saw men too much sub specie aeternitatis.

It is very important that we should understand what was behind his actions, and I do not think we shall understand unless we realize that he, like many poets of our time, went into politics for what he as a poet could get out of it. He is, indeed, the perfect contemporary example of the poet as parasite. This is not to deny the passionate intensity with which he felt the various struggles in which he was involved; it is to suggest that beneath this conviction lay the more deeply rooted impulse towards material which should inspire and satisfy the poetic faculty. Neither his enthusiasm nor his achievements on behalf of an Irish national culture and Irish political independence can be disputed; but it was in and through his poetry that he was most a patriot. When, as a poet, he had transferred the blood of nationalism into his own poetic vein, he fell away from politics into the philosophical mysticism with which his life and mind were so curiously streaked. By this time he was an old man. Yet, so far from being silenced by old age, he turned upon it with the eager ferocity of genius, battened upon it, made it yield up some magnificent poems.

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress…

Consume my heart away; sick with desire

And fastened to a dying animal

It knows not what it is…

Before this monument raised out of physical humiliation, we stand dumb. “For men improve with the years,” Yeats once wrote. Very few poets, though, have improved with the years: that he should have advanced in poetic development almost up to the day of his death implies an unusual integrity and compels us to examine with respect the attitude to life and art which made this development possible.

Yeats himself summed it up, I think, in “The Fisherman,” when he said:

It’s long since I began

To call up to the eyes

This wise and simple man.

All day I’d looked in the face

What I had hoped ‘twould be of the old

To write for my own race.

And the reality…

For Yeats, as Stephen Spender suggested in The Destructive Element, as L.A.G. Strong claimed in his recent obituary essay, was, in spite of lapses and contrary appearances, a realist. For the poet, realism consists first and foremost in using his poetical faculty to penetrate beneath the surface of reality, and in refusing to put more into his poetry than his imagination warrants. Only by such strict discipline will he attain wisdom and virtue–the specific wisdom and virtue of the poet.

I have spoken of Yeats’ incursions into politics. There was the time when he threw himself into the boycott of a royal visit to Ireland; there were the years when he sat in the Irish Free State’s Senate. But, paradoxically, his greatest political service to his country was done as a spectator. I refer to the great political poems, “Easter, 1916,” “Sixteen Dead Men,” and “The Rose Tree,” and I have used the word “spectator” deliberately. If we read these poems dispassionately, we must be struck by the air–not exactly of aloofness or detachment–but of non-partisanship which lies at the heart of their deep emotion. We get the impression that, though in one sense he was with the rebels, he was not of them; he writes of them with fire and tenderness, but he does not allow his emotion to overstep the reality, to pretend that even spiritually he had participated in their action. On the contrary, he confesses his initial skepticism about the 1916 rising “Being certain that they and I/But lived where motley is worn.” And then that superb close:

We know their dream; enough

To know they dreamed and are dead;

And what if excess of love

Bewildered them till they died?

I write it out in a verse–

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

So again with “The Rose Tree,” in words as simple and as memorable as those of any ballad in the great Irish tradition of the political ballad, he gives for all time the significance of those men who went deliberately to their death in the belief that nothing else would rouse their country to freedom:

“But where can we draw water,”

Said Pearse to Connolly,

“When all the wells are parched away?

O plain as plain can be

There’s nothing but our own red blood

Can make a right Rose Tree.”

Some of these men were poets themselves; but they would have been soon forgotten, or remembered only as names in a roll of honor, had not Yeats written it out in a verse. They and he both played their part, and no one reading these poems can deny that Yeats achieved his desire–“To write for my own race/And the reality.” A double desire which might have proved the ruin of any but a poet of the highest integrity.

It is no contradiction to say that a poet is both realist and legend maker, for legend is a heightening of reality, a molding of it into durable form. Yeats was nothing if not a maker of legend. Beginning with the folklore of his own country, he went on to make legends of his friends and those whom he most admired or hated, of the places he loved in boyhood and mature age. Of all these people, except perhaps for John Synge, the leaders of the Easter Rebellion were the most significant in their lives and deaths, the most deeply touched with that “excess of love” which calls as irresistibly to the poet as a magnet to iron filings. Therefore it is natural that the poems which he wrote about them should be also the greatest legends he created. Compared with these, even such noble and witty poems as “In Memory of Major Gregory,” “An Irish Airman Foresees His Death,” or “The Tower” appear of a paler, more tenuous reality.

Yeats’ work shows, almost throughout, an unsolved conflict between the realist and the romantic, between the questing imagination and the inherited tradition. “Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone,” he sighed in one poem; and, though the Easter Rebellion gave this the lie, it was only to be followed by the Anglo-Irish War and the struggle between Free Staters and Republicans–struggles that had very much less romance though far greater efficiency about them. These latter wars seem to have sickened Yeats of politics. The mood of “The seeming needs of my fool-driven land” returned. When he wrote “It is time that I made my will,” he named the proud and independent as his heirs:

They shall inherit my pride,

The pride of people that were

Bound neither to Cause nor to State,

Neither to slaves that were spat on,

Nor to the tyrants that spat,

The people of Burke and of Grattan

And again:

We were the last romantics-chose for theme

Traditional sanctity and loveliness…

This is all of a piece with his aristocratic tradition–the tradition of the cultured eighteenth-century landowner which permeated intellectual Anglo-Irish society and flared up to a grand finale in Yeats’ own work. The virtues of this tradition, this society, were less and less appropriate to the world in which Yeats lived and wrote. Therefore he was a romantic as well as a realist. Therefore, as one critic has said, he found “no subject of moral significance in the social life of his time.” No subject, we might amend this, but the Easter Rebellion. His realism and romanticism are summed up best in his own remarkable lines:

Things fall apart; the center cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1939/v30n11-mar-07-1939-NM.pdf