Byron’s blistering speech in defense of the Luddites to the House of Lords in 1812.

‘First Speech Of Lord Byron: Voice of the Great Poet Raised in Defense of the Proletariat’ from The Worker (New York). Vol. 15 No. 29. October 14, 1905.

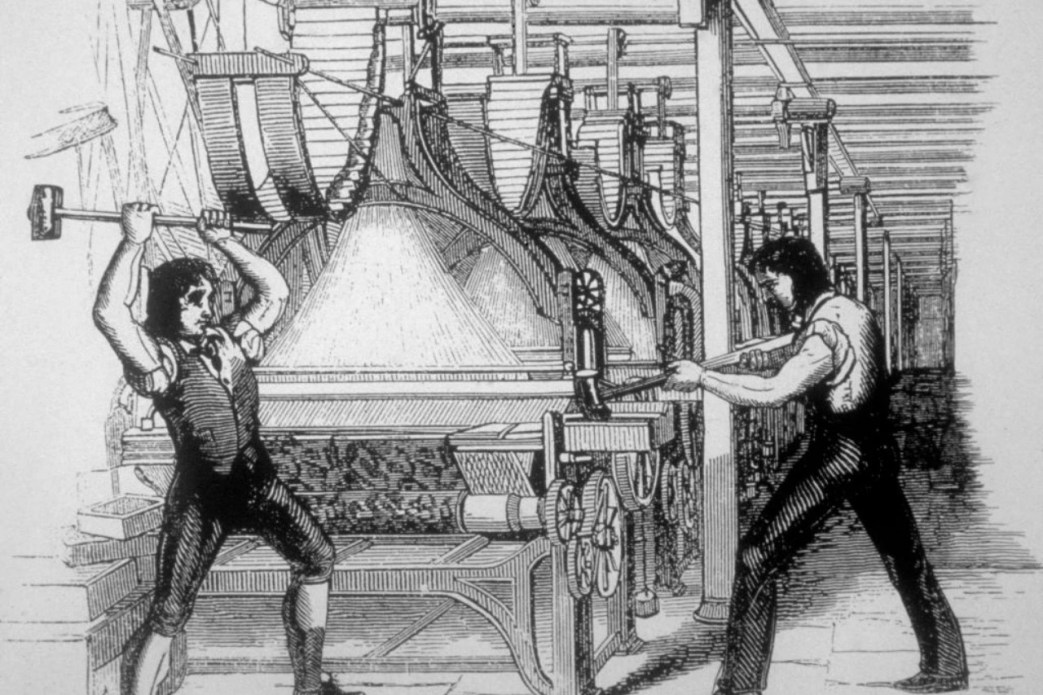

This first speech of Byron in the House of Lords was delivered on Feb. 27, 1812, upon the second reading of the Frame-Work Bill, which was introduced in order to terrorize the Luddites. The introduction of machinery then going on, following a disastrous period of war, had brought thousands of the working class to starvation. The men rendered desperate by the hunger of themselves, their wives and children, marched about smashing the frames. The punishment on conviction for frame smashing was transportation. This, however, was not sufficient for the blood-sucking capitalist at that time making their thou- sands per cent (see “Social England,” edited by H.D. Traill, articles “Commerce” and “Industry”), and a bill was introduced making frame-work smashing punishable by death.

To enter into any detail of the riots would be superfluous. The House is already aware that every outrage short of actual bloodshed has been perpetrated, and that the proprietors of the frames obnoxious to the rioters, and all persons supposed to be connected with them, have been liable to insult and violence. During the short time I recently passed in Nottinghamshire, not twelve hours elapsed without some fresh act of violence; and on the day I left the county I was informed that forty frames had been broken the preceding evening; as usual, without resistance and without detection.

Such was then the state of that county, and such I have reason to believe it to be at this moment. But whilst these outrages must be admitted to exist to an alarming extent, it cannot be denied that they have arisen from circumstances of the most unparalleled distress. The perseverance of these miserable men in their proceedings tends to prove that nothing but absolute want could have driven a large and once honest and industrious body of people into the commission of excesses, so hazardous to themselves, their families, and the community. At the time to which I allude, the town and county were burdened with large detachments of military; the police were in motion, the magistrates assembled, yet all the movements, civil and military, had led to nothing. Not a single instance had occurred of the apprehension of any real delinquent actually taken in the act, against whom there existed legal evidence sufficient for conviction. But the police, however useless, were by no means idle. Several notorious delinquents had been detected, men liable to conviction on the clearest evidence of the capital crime of poverty, men who had been nefariously guilty of lawfully begetting several children, whom, thanks to the times, they were unable to maintain. Considerable injury has been done to the proprietors of the improved frames. These machines were to them an advantage, inasmuch as they superseded the necessity of employing a number of workmen, who were left in consequence to starve.

By the adoption of one species of frame in particular, one man performed the work of many, and the superfluous laborers were thrown out of employment. Yet it is to be observed that the work thus executed was inferior in quality, not marketable at home, and merely hurried on with a view to exportation.

It was called in the cant of the trade by the name of “spired work.” The rejected workmen, in the blindness of their ignorance, instead of rejoicing at these improvements in arts so beneficial to mankind, conceived themselves to be sacrificed to improvements in mechanisms. In the foolishness of their hearts they imagined that the maintenance and well-doing of the industrious poor were objects of greater consequence than the enrichment of a few individuals by any improvement in the implements of trade, which threw the workmen out of employment, and rendered the laborer unworthy of his hire.

All this has been transacting within 130 miles of London, and yet we, “good easy men, have deemed full sure our greatness was a ripening,” and have sat down to enjoy our foreign triumphs in the midst of domestic calamity. But all the cities you have taken, all the armies which have retreated before your leaders, are but paltry subjects of self-congratulation, if your land divides against itself, and your dragoons and your executioners must be let loose against your fellow citizens. You call these men a mob, desperate, dangerous, and ignorant; and seem to think the only way to quiet the bella multorum capitum [many-headed beast] is to lop off a few of its superfluous heads.

Are we aware of our obligations to a mob? It is the mob that labor in your fields and serve in your business, that man your navy and recruit your army, that have enabled you to defy all the world, and can also defy you when neglect and calamity have driven them to despair. I have traversed the seat of war in the Peninsula. I have been in some of the most oppressed provinces of Turkey, but never under the most despotic of infidel governments did I behold such squalid wretchedness as I have seen since my return in the very heart of a Christian country.

And what are your remedies? After months of inaction, and months of action worse than inactivity, at length comes forth the grand specific, the never-falling nostrum of all state physicians, from the days of Draco to the present time. After feeling the pulse and shaking the head over the patient, prescribing the usual course of warm water and bleeding, the warm water of your mawkish police, and the lancets of your military, these convulsions must terminate in death, the sure consummation of the prescription of all political Sangrados. Are these the remedies for a starving and desperate populace? Will the famished wretch who has braved your bayonets be appalled by your gibbets?

The framers of such a bill must be content to inherit the honors of that Athenian conqueror, whose edicts were said to be written, not in ink, but in blood. But suppose it passed, suppose one of these men, as I have seen them, meagre with famine, sullen with despair, careless of a life which your lordships are perhaps about to value at something less than the price of a stocking frame, suppose this man surrounded by the children for whom he is unable to procure bread at the hazard of his existence, about to be torn forever from a family which he lately supported in peaceful industry, and which it is not his fault he can no longer so support, suppose this man–and there are ten thousand such from whom you may select victims–dragged into court to be tried for this new offense, by this new law, still there are two things wanting to convict him, and these are, in my opinion, twelve butchers for a jury, and–a Jeffreys for a Judge!

The Worker, and its predecessor The People, emerged from the 1899 split in the Socialist Labor Party of America led by Henry Slobodin and Morris Hillquit, who published their own edition of the SLP’s paper in Springfield, Massachusetts. Their ‘The People’ had the same banner, format, and numbering as their rival De Leon’s. The new group emerged as the Social Democratic Party and with a Chicago group of the same name these two Social Democratic Parties would become the Socialist Party of America at a 1901 conference. That same year the paper’s name was changed from The People to The Worker with publishing moved to New York City. The Worker continued as a weekly until December 1908 when it was folded into the socialist daily, The New York Call.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-the-worker/051014-worker-v15n29-electionspecial.pdf