The man who would go on to lead the Communist Party for much of its first decade, C.E. Ruthenberg, gives us this detailed report on 1,600 insurgent women garment workers in a bitter contest with Cleveland capitalists in 1911.

‘The Cleveland Garment Workers Strike’ by Charles E. Ruthenberg from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 12 No. 3. September, 1911.

THE garment workers of Cleveland have been on strike for two months at the time this article is written. In the face of the most bitter opposition the International Garment Workers’ Union has ever met with, in the face of the brutality and violence of the worst lot of hired guards ever used in a contest of this character, in spite of the united effort of the capitalist dailies to prejudice the public against the strikers and to break their ranks by publishing lying stories about the strikers going back to work, and in spite of the arrest of hundreds of pickets, the garment workers are as firm in their demands as when the strike began, and they hold a stronger position.

The workers in this contest did not make the usual mistake of giving their employers weeks and months to prepare for a strike. They struck their blow the moment their demands were refused. On June 5th the demands of the union were presented to the employers. On June 6th a mass meeting of the workers was called and the situation laid before them. The following morning the union officials again tried to secure consideration of workers’ demands, of which the main points are, a fifty hour week; no work on Saturday afternoon nor on Sundays; not more than two hours’ overtime five days per week; double time for overtime for week workers; the observance of all legal holidays; ho charge for machines, power or appliances, nor for silk and cotton; no inside contracting; no time contracts with individual employes; prices for piecework to be adjusted by a joint price committee, to be elected by employes in the shops, the outside contractors and a representative of the firm. The employers absolutely refused to deal with the representatives of the unions.

The workers had begun their tasks at the tables and machines as usual the morning after the mass meeting, and probably none of the employers guessed that the strike was imminent. But when word was passed from shop to shop at 9 o’clock that the bosses had refused to see their representatives and that they were to walk out at ten, the workers were ready. When the hands of the clock pointed to that hour they dropped their work and filed out of the factories.

On St. Clair avenue and intersecting streets, where a large number of factories are located, the streets were soon filled with strikers. In accordance with instructions received they formed in line and marched from factory to factory, augmenting their strength at each place until more than seven thousand were in line. They thus gave the first impressive demonstration of their strength. After passing through the down-town section the paraders proceeded out Superior avenue to the plant of H. Black & Co. This is one of the largest concerns in Cleveland and some difficulty was expected in getting the workers in this factory to join the strike, but when the strikers counter-marched before the plant they were joined by practically every worker employed by this concern.

The garment workers are fortunate in having an industrial form of organization and in making their demands as one organization and not as the demands of separate unions. Although there are five unions concerned in this strike they did not carry on separate negotiations and go on strike as individual organizations. Their demands were presented by the officials of the International Garment Workers’ Union, and when they struck, cloak cutters, cloak makers, shirt makers, cloak and shirt pressers and finishers and outside contractors struck as one organization. And ever since they have stood together as one organization and have ‘refused to deal with their employers in any other way than through the joint board representing” all the unions.

The Employers’ Association has followed the usual tactics in trying to break the strike. Blackguards, ex-criminals and ruffians of all kinds have been employed through private detective agencies, ostensibly as guards, but in reality to instigate rioting and violence, which is laid at the door of. the strikers by the capitalist press. “Facts,” the official organ of the Employers’ Association of Cleveland, thus sums up the result:

“The Cleveland strike has resulted in one death, thirteen serious riots resulting in shooting, slugging, smashing of windows, destruction of property, severe fighting and assaults, which were only quelled by calling out the police reserves; one vitriol throwing affair; three shooting affrays of major character not counting riots; one stabbing affray; twenty-two grave assaults and many street battles; many riotous affairs in which men were beaten up, wounded, and shots were fired; several hundred cases of violence where blows have been struck and hundreds of cases of missile and egg throwing and disorderly conduct. Over three hundred arrests have resulted.”

Here is one instance which will serve to explain how these riots and disturbances originated:

R.J. Snyder, E.J. McCarthy, Frank Deering and Ed Elliott, all guards in the employ of the manufacturers, were driving down Payne avenue in an automobile at the rate of forty miles an hour. Being drunk or inexperienced in handling an automobile, they lost control of the machine and crashed into a telegraph post. Snyder had his skull fractured and the three other guards were injured more or less seriously. People living in the neighborhood called an ambulance in which Snyder was taken to a hospital. They were engaged in caring for the other guards when another automobile load of guards came along. Without asking or waiting for any explanation these guards drew their billies and blackjacks, rushed into the crowd and clubbed and beat everyone within reach.

The facts in this case were too palpable to be concealed, and other cases of violence and destruction of property upon investigation show the same result. A non-union shop was set on fire and strikers accused of being the incendiaries. Investigation by the fire marshal’s office brought out the fact that guards in the employ of the manufacturers were the real criminals. Warrants were sworn out for the arrest of these guards, but before they could be served they had disappeared and the detective agency which had employed them disclaimed any knowledge of their whereabouts.

It is not to be supposed that these seven thousand men and women carrying on a contest for wages which will give them a decent subsistence and for working conditions which will enable them to live as human beings have been always peaceable and have always refrained from meeting violence with violence. Can it be expected of these workers, fighting for their very lives, that they turn the other cheek when attacked by ruffians brought into the city by their employers? But it can be said without fear of contradiction that nine-tenths of the violence which is laid at the door of the strikers has been the result of aggression on the part of the so-called “guards,” hired to create disturbances.

The Cleveland police department has been entirely at the service of the Manufacturers’ Association. One-third of the police force is constantly on duty at the various factories. At the plant of H. Black & Co. a few days ago there were ten burly policemen guarding the factory against four girl pickets, not any of whom was much over sixteen years of age.

The police, evidently acting under instructions, have harassed the strikers in every way possible. While guards, carrying revolvers and blackjacks, have not been molested, though violating the law which forbids the carrying of concealed weapons, girl pickets have been arrested on charges brought under obsolete ordinances, which no one ever heard of until the present strike. In the disturbances resulting from attacks on strikers by guards the police have invariably taken the part of the guards and clubbed and arrested strikers and bystanders, whether guilty of any lawlessness or not.

It is only necessary to read between the lines in the following report published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, of a charge of mounted police, for evidence of this fact:

“They (the mounted police) galloped headlong at the crowd when they first appeared and the hundreds who blocked the street fled in terror. They swung their clubs when they reached the crowd and forced their way through, driving scores before them down the streets. Some groups that ran from them were chased for blocks…There was little resistance offered the horsemen.”

Brave men, indeed, to ride roughshod among unarmed men and women who flee in terror and offer no resistance!

In order to keep pickets away from the factories the police established what they called “dead-lines” about the garment factory district in the downtown section of the city, through which no one was allowed to pass without explaining his business. No authority existed for forbidding the people of Cleveland from passing up and down any street of the city, but although this fact was called to the attention of the head of the police department and the mayor, the “dead-lines” were maintained until the strikers themselves set them at defiance. A procession of strikers, their wives and relatives was organized and ten thousand strong they marched from the union headquarters through the heart of the city to the factory district and through the “deadlines.” Since this parade the police have forgotten that “dead-lines” had been established.

There are 1,600 girls out in this strike. Under the direction of Miss Pauline Newman and Miss Josephine Casey, both organizers sent to Cleveland by the International Garment Workers’ Union, these girls are doing wonders. When the strike began very few of them were in the unions. Today they are practically all organized and firmer in their demands and more ready to do picketing and other work than the men. Miss Newman, who took part in both the shirt waist makers’ strike in New York and the garment workers’ strike in Philadelphia, says that the spirit manifested by the girl workers in Cleveland is an inspiration to everyone connected with the strike.

At one of the factories forty-five girls were arrested at one time. No sooner were they locked up than one of the girls proposed: “I move that we elect a chairman and hold a meeting.” The chairman was duly named and a committee elected to draw up resolutions condemning the police.

Girls who maintain this fighting spirit in police cells are not going to be easily beaten.

Officers of the International Union say that the Cleveland strike is the bitterest fight they have been in. Although unable to operate their factories, the employers are maintaining a firm front. When members of the State Arbitration Board came to Cleveland to investigate the strike they refused absolutely to place their case before the board, although union officials had manifested their willingness to submit the demands of the workers to arbitration. Various firms have’ tried to open shops in the small towns about Cleveland, but have not succeeded in operating them successfully. At Canton, Akron, Conneaut, Ashtabula, Painesville, Sandusky, Elyria and a number of other places these shops have been closed through aggressive work of organizers and pickets from Cleveland co-operating with the central bodies of the unions in these towns.

The Employers’ Association has tried to bring in strikebreakers from other cities, but with little or no success. Out of thirty-five of the larger shops concerned, only eleven are making any at- tempt to operate at all. In these eleven factories not over five hundred strikebreakers are employed.

In some of these factories, strikebreakers are being held in what practically amounts to peonage. Once outside of the shops they are kept there under guard, sleeping and eating their meals inside of the factories. They soon grow tired of such a life and if given an opportunity are only too anxious to leave.

The Socialist Party has not neglected the opportunity presented in this strike to show up the class character of the municipal government and the courts of Cleveland. When a judge declared that carrying concealed weapons by strikebreakers, which is absolutely forbidden by city ordinance, was not illegal, but that calling “scab” at strikebreakers justified arrest, the eyes of some of the workers were opened.

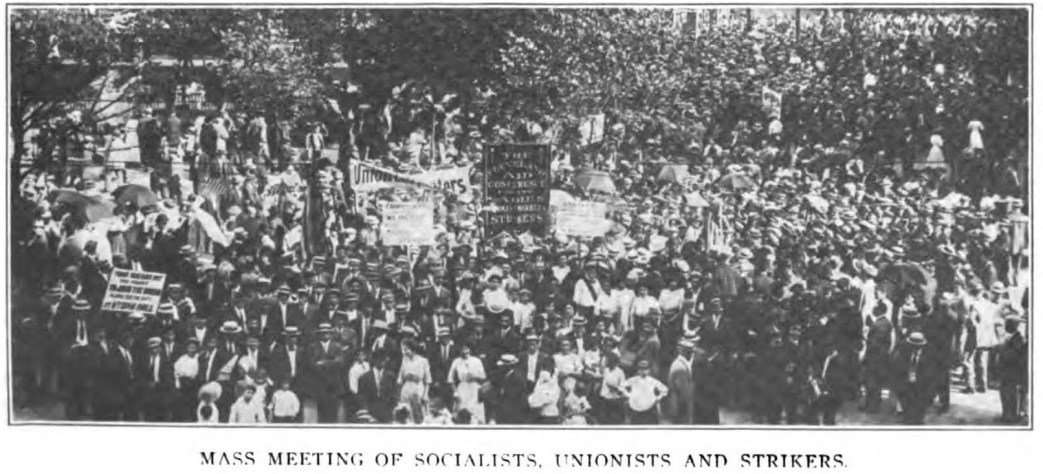

Socialist speakers have been addressing large meetings held under auspices of the union, and Socialist soap-boxers are holding meetings regularly in the strike district. Especially active has been the Jewish branch of the Socialist Party, which, through the Garment Workers’ Aid Conference, took the leading part m arranging a monster protest demonstration against the city administration because of its use of the police in the interest of the employers. Between 15,000 and 20,000 strikers, unionists and Socialists took part in this demonstration. Since this time the police have been a little more active in protecting strikers from the brutality of the guards. Evidently the capitalist administration fears the political effect of too open use of the police department against the strikers, especially since the Director of Public Safety, who has control of the police force, is the Republican candidate for mayor.

The strike at the time this article is written seems to be deadlocked. The workers are firm in their demands and are stronger than when the strike began. When the strike was called 3,000 out of the total of 7,000 workers who left the shops were members of the unions. Today practically every one of the seven thousand is a member. The employers’ association, on the other hand, absolutely refuses to deal with the union officials, but each day that the workers remain firm adds to their strength. The busiest season of the year in the garment making industry is at hand, and every day the factories remain closed the employers are losing thousands of dollars’ worth of orders. They have boasted in the past in at Cleveland has the third largest garment making industry in the world, but unless they yield in this strike this prestige will soon be lost. If the workers maintain their splendid solidarity, if all the unions fight together to the end as they have been fighting during the past two months, there is hardly a doubt but that the victory will ultimately be theirs.’

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of original issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v12n03-sep-1911-ISR-gog-Corn.pdf