Legendary journalist Agnes Smedley, then working for the New York Call, witnesses Jim Larkin’s sentencing for ‘criminal anarchy,’ and is able to accompany his train to prison at Sing Sing.

‘Jim Larkin Hurried to Sing Sing’ by Agnes Smedley from Truth (Duluth). Vol. 4 No. 20. May 14, 1920.

Defendant, Convicted as ‘Anarchist,’ Not Permitted to Consult His Friends or Attorney. DEFENSE OVERRULED. Appeal to Higher Courts Planned–Prisoner Sends Message of Unshaken Faith in Socialism.

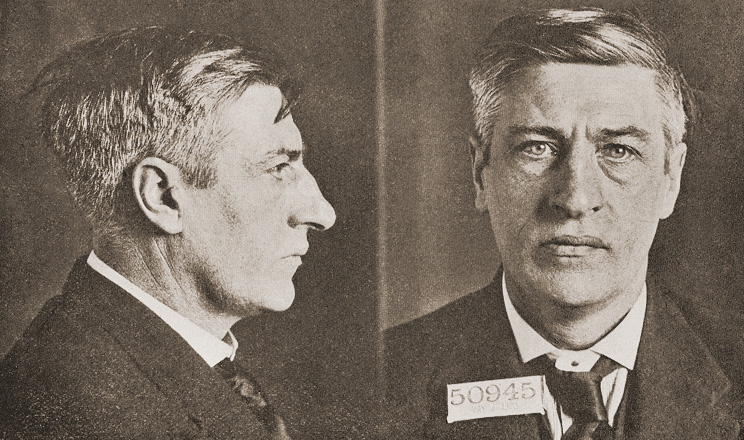

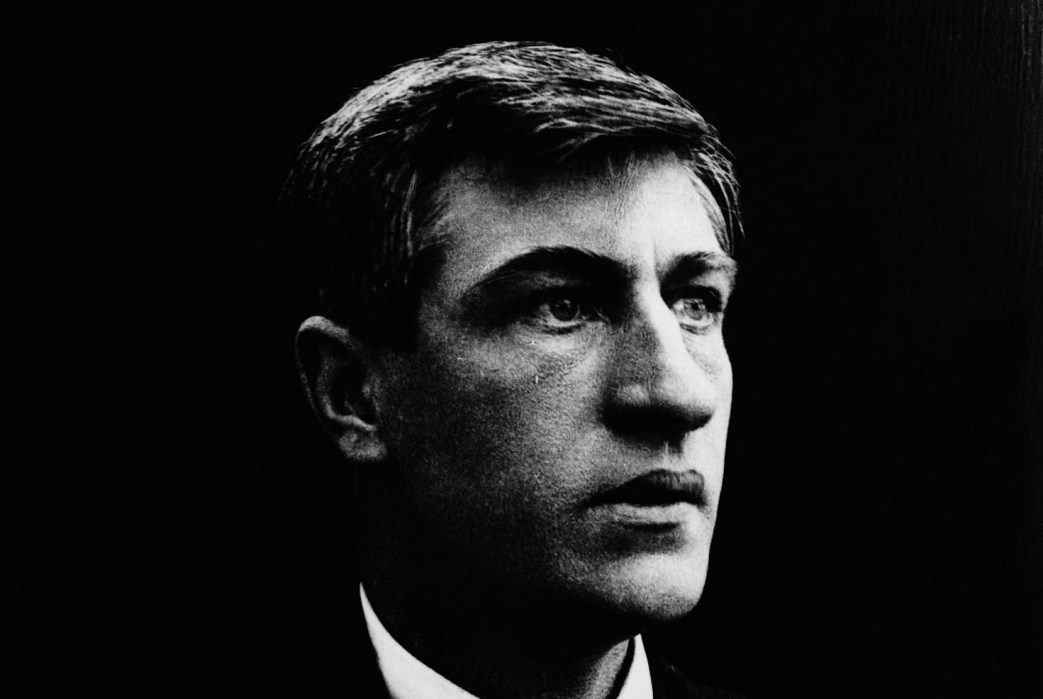

James Joseph Larkin, Irish labor leader, founder and commander-in-chief of the Citizen’s Army of Ireland, is now prisoner number 71161 at Sing Sing prison. He was sentenced yesterday to serve from 5 to 10 years at hard labor by Judge Bartow S. Weeks in the Supreme Court, following his conviction last week on a charge of “criminal anarchy.”

After warning the courtroom that any noise of approval or disapproval would be met with arrest, Judge Weeks asked Larkin if he had anything to say before receiving sentence.

Larkin replied, “Nothing.”

“I find nothing in the record in the case to indicate why the full penalty of the law should not be imposed upon you,” continued the judge, and forthwith imposed the sentence.

Courtroom Silent.

The courtroom above the marshals at his back, his arm folded and his chin held high. He gazed waveringly into the eyes of the judge.

Judge Weeks denied all motions made by Attorney Walter Nelles for the defense, sacrificed his customary hour’s peroration on the virtues of the present social system and the viciousness of the defendant, and ordered Larkin to be sent mediately to Sing Sing. The entire proceeding was over in less than ten minutes.

At 11:57, just one hour after sentence was pronounced, Larkin, in company with two marshals, was rushed from the Tombs to the Grand Central Station and on to a train bound for Ossining, special precautions being taken that he should consult with no friends, not even his attorney, before leaving.

Larkin Sends Message.

A Call reporter, however, boarded the safe train and accompanied Larkin and the marshals all the way to prison and obtained a last message from Larkin to the working people of the world, leaving Sing Sing only after the prison doors closed behind the labor leader, shutting him away from the world. Leaving the train at Ossining, Larkin and The Call reporter, accompanied by the marshals, walked over the hills and down the road to the cold, gray prison to stone and iron.

Larkin talked of the working class movement in the United States, of the necessity of workers coming into one big union, and of the possibilities for Irish freedom if the labor movement of Engla will live up to its pretensions and professions by declaring a general strike and forcing the British army to evacuate Ireland.

Number 71,161.

By 2 o’clock Larkin’s pedigree had been taken by Sing Sing officials and he had been numbered prisoner No. 71,161.

He was still smoking his pipe, his huge, slightly stooped shoulders and his head, touched with gray, looming far above the marshals and prison guards who swarmed about him like flies.

Again the contrast between the labor leader and his captors was harsh and brutal. Larkin’s strong, kind face was thrown into relief against the thin, cruel faces of prison officials, or the fat, bloated faces of the marshals. He appears as a Gulliver surrounded by Lilliputians. He seemed to personify the working class.

“Always Take Pedigrees.”

“Why do they take his pedigree?” asked the Call reporter of a marshal “Why” replied the marshal scornfully.

“Why, because if he gets sick and dies, don’t they have to tell someone? They always take pedigrees.”

Larkin was led away by the Lilliputians, and the Call reporter stood observing a great gate of steel and the huge lock on it.

Then, turning, on the hill behind she saw the columns of a church devoted to the service of Christ. It faced the long, gray prison with steel bars stretched across the face or each window. It looked down over the stone prison walls where swarms of little men were pounding piles of stone.

Detectives Swarm Courthouse

The Imprisonment of the Irish labor leader was the climax of a number of ugly scenes in the court room and in the courthouse in the morning, preceding Larkin’s sentence.

The corridors of the courthouse were filled with huge, burly detectives and plainclothes men who stood in line and talked with the men and women waiting for the courtroom doors to open. Dozens of them stood in groups or shoved about through the crowd, guns showing through their coats.

One of them, noticeable for his bulk and for the brutality of his face, received information from his men and gave orders in a low, violent voice. Standing in a group of four, he gave the following orders, all of which were distinctly heard by a Call reporter:

“watch that guy standing over there with a derby.”

“D’ya see that g-d- – standing there with a cigar in his mouth and a smile–be ready for him!”

“And the little guy there with a green hat on—”

Detectives Quiz Nunan

Two huge detectives made for “the little guy with the green hat.”

“You,” the speaker bawled at him, “did you say you don’t care for this country?”

“Are you an American citizen?” bawled the other.

The “little guy with the green hat” happened to be Peter Nunan, an Irishman, vice-president of the New York Gaelic League. He stood with his hands in his pockets watching as they came at him.

“I am a citizen of the Irish Republic,” he replied, whereupon one of the detectives pushed him in the chest, and both of them grabbed him by the shoulders and forcibly ejected him from the courthouse.

Every Man Forcibly Searched.

Every man who entered the court room was forcibly searched by the detectives, and the names and addresses of both men and women were taken. In the courtroom itself the detectives placed themselves in dramatic, strategic positions, apparently ready to shoot at any person who blinked an eyelash. Despite all precautions, and despite the fact that the atmosphere was vibrant with “law and order” violence, Gertrude Nafe, an American woman and a teacher, living at 144 Waverly Place, arose when Jim Larkin was brought into the courtroom, and remained standing until he was taken away. An officer led her before Judge Weeks, who angrily asked her the meaning of her action.

“Did you hear my order?” he asked.

“I did,” replied Miss Nafe. “The order of the court stated ‘speaking’. I did not speak. For the sake of the defendant I said nothing, but I arose to show my respect for the man whom I respect more than any other person in America. Just as one is forced to rise because of the position of the judge when he enters the courtroom, so did I rise, out of respect for James Larkins record.”

Miss Nafe Ordered Ejected.

The only reply of the judge was to order that Miss Nafe be immediately ejected from the court.

No other person was brought before the court, although several arose when Larkin was led from the room to shake hands with him. The detectives were on their feet immediately.

A number of women left the court sobbing, while men with angry faces arose immediately and left. Aside from these occurrences, the display of violence, the “demonstration” so widely heralded by the police, failed to materialise.

Defense Motions Denied.

The motions made by Walter Nelles, attorney for Larkin, and immediately and quickly denied by the Judge, included the following:

1. That the verdict be set ride on the grounds that it is contrary to law, against the evidence, against the weight of evidence, and on each and every exception taken by the defendant in the course of the proceedings.

2. A motion for arrest of judgement on the grounds that the facts stated in the indictment do not constitute a crime, that the defendant was denied trial by jury as guaranteed to him by the Constitution, that in arrest he was denied the due process of law guaranteed by the constitution of this state and 17 the 11th amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

3. A motion that the action of the court in taking the names and addresses of every person who entered the courtroom be made a part of the record.

On his way to Sing Sing, Larkin seat a message of friendship and courage to his friends and Comrades.

Larkin Reiterates His Stand.

“I have the same opinion as I expressed in court throughout the trial,” he said. “I have always held those opinions and I will always hold them. There is no danger of my changing them.

“I know that Socialism is the only hope for the working class. The salvation of the workers will come through the One Big Union. I believe it to be of great importance that Debs be released as soon as possible, and that our Comrades should work for this end.

Irish Situation Discussed.

“To me the most interesting feature of conditions over here right now is this new movement among the labor forces of America to demand that the British labor movement compel the evacuation of Ireland by British troops.

“The hope for the freedom of Ireland right now lies in the exertion of the working class movement of Great Britain. We, in America, mast insist upon, and force the British labor movement to live up to its professed principles and statements, and compel the British tools to evacuate Ireland. If this means a general strike in England, then they must call a general strike.

“I congratulate the British government on its astuteness and cleverness in getting the American authorities to keep me outside its realm. I also thank Assistant District Attorney Rorke and the British authorities for having found me a new birthplace, a new father and a new mother!

Sends Greetings to Comrades.

“As for the two convictions in Ireland of which I was accused, and evidence of which the British government kindly supplied Rorke, and of which I myself spoke, they were true in so far as I stated them to be true, but not as Rorke and the court tried to make them appear. The charge of larceny was but the outcome of the class struggle, and is one of the many methods used by the authorities and the British government to destroy the movement.

“As for the conviction for sedition against the British government, this a conviction for which no rebel need be ashamed.

“I send my greetings to all my Comrades at home in Ireland. I am just as sure of their loyalty now as I ever was. I know they will prove true to the principles for which they are working. They know that the only real struggle is the labor struggle.

Socialist Unity Here

“I also send my greetings to the militant section of the British labor movement. And to my Comrades in America I send greetings and appreciation for what they have done for me. I hope for unity in the Socialist movement here, but unity must be based on the foundation of real class consciousness. Our slogan must be now as ever, No compromise, no political trading.

Stands by Principles.

“Tell my Comrades that I am with them in soul and body and that I know they will keep up the struggle. I joined the Socialist movement at the age of nine, and now, 33 years later, I know that it is still the only hope of the people of the world.

“My life has been lived in accordance with its principles, and thought and energy has been directed in that direction. I will never depart from that principle in thought or action. I cannot; it is of me, and I am a part of it.”

Walter Nelles, attorney for Larkin, said yesterday that he intended to file papers for an appeal of the case to the Appellate Court and, failing there, would go to the United States Supreme Court. In the meantime, Larkin is denied bail and is forced to start his sentence of hard labor at Sing Sing.

Truth emerged from the The Duluth Labor Leader, a weekly English language publication of the Scandinavian local of the Socialist Party in Duluth, Minnesota and began on May Day, 1917 as a Left Wing alternative to the Duluth Labor World. The paper was aligned to both the SP and the IWW leading to the paper being closed down in the first big anti-IWW raids in September, 1917. The paper was reborn as Truth, with the Duluth Scandinavian Socialists joining the Communist Labor Party of America in 1919. Shortly after the editor, Jack Carney, was arrested and convicted of espionage in 1920. Truth continued to publish with a new editor JO Bentall until 1923 as an unofficial paper of the CP.

PDF of full issue: https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn89081142/1920-05-14/ed-1/seq-2