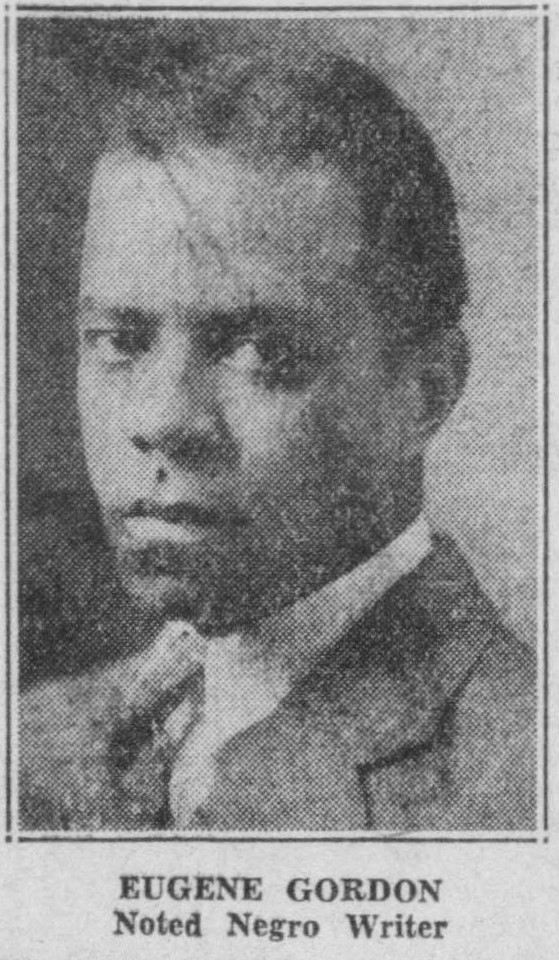

Eugene Gordon assails the Black press for not recognizing the role and plight of Black miners during the desperate struggle in Harlan, Kentucky and in the Ohio-West Pennsylvania coal fields in the early 1930s.

‘Harlan–and the Negro’ by Eugene Gordon from Labor Defender. Vol. 6 No. 11. November, 1931.

UNDER the policy of race separatism sponsored by the United States government and adhered to by chauvinistic whites, Negroes have come to look upon any situation involving whites as no Negro’s business. “It is the white man’s fight,” they say; “let him settle it.” This attitude has characterized the Negro not only with respect to the political and social life of the whites, but also with respect to economic upheavals. The reason is obvious, of course: shut out for generations from participation in American life except as a labelled and conspicuous minority, the Negro has developed race consciousness instead of class consciousness; has grown to hate the white man because he is white, instead of hating some white men because some are enemies of the class to which most Negroes nominally belong.

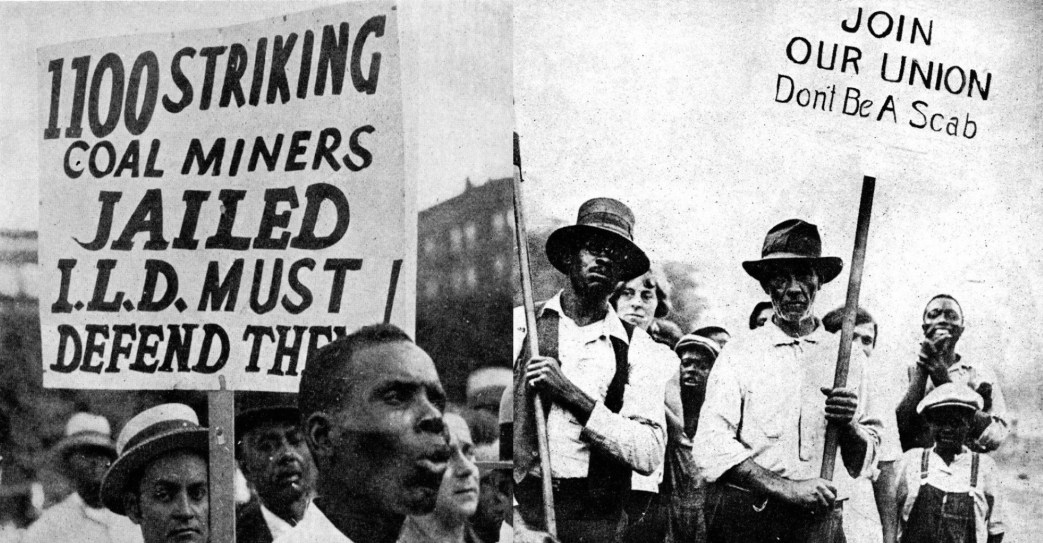

We are less concerned, however, about the reason for this attitude than we are about the results that emanate from it wherever it operates. For this narrow and bigoted policy on the part of a great number of Negroes has blinded them to suffering within their own ranks. A considerable number of Negro newspapers, for instance, have had little or nothing to say regarding thousands of black miners of Pennsylvania and Kentucky; even in the case of those Kentuckians who have been charged with murder and who now face death in the electric chair. As a matter of pigheaded and doltish policy, a large section of the colored press has refrained from commenting on the strikes in the coal fields. This policy is dictated by a disdainful aloofness to all situations in which no Negroes are thought to be involved. The papers to which I refer do not know that Negroes as well as whites are suffering from lack of food and clothing. The historical policy of this section of the press is to let “white folks” settle their affairs, and pursuing this policy, the editors or publishers have been led into the stupid blunder of neglecting the welfare of the very people they allegedly are most interested in, the black working class.

Wherever there are Negro miners their suffering has, as a matter of course, been more acute than that of the whites. The first reason is that they are segregated in the company patches, being compelled to live in the least desirable spots of these miserable stockades. The second is that they are discriminated against in the company stores: they are invariably forced to wait aside while one white after another enters and is served. This especial species of discrimination is intended to impress upon white and black miners the degraded status of the Negro toilers. So although they are accepted into the revolutionary unions by their white comrades on the common basis of workers, their treatment by the mine and the civil authorities is designed to create doubt in the minds of the whites whether these Negroes are not, after all, inferior to the whites. Thus although they work together, the white and the black toilers in the mines are perpetually conscious of that unseen and subtle force which interpenetrates their very lives, striving to disintegrate their fraternal relationship. Especially do the mine operators and the civil authorities connive to keep white and black workers separated in their social contacts. The black miner suffers therefore more acutely than his white fellow worker, for, whereas the whites suffer the usual disabilities incidental to striking, the blacks, in addition, suffer because they are black. It is out of such a welter of oppression, persecution, and inhumanity that the situation arose which precipitated charges or murder against five Negro miners in Harlan County, Kentucky. It is a case of capitalist war against workers; it is a case, moreover, of a capitalist war against black workers. They are despised and degraded because they are members of the working class; they are further oppressed and debased because they are members of the black working class.

At Harlan today there are 34 white and black miners awaiting electrocution on framed-up charges. The International Labor Defense has disclosed that a number of stool pigeons, planted among the miners by the coal operators, will be used as the chief witnesses against these starving men when they are brought into court. The workers’ defense at Harlan points out a fact and suggests a program that the Negro press and the Negro middle-class in general ought to heed. The fact that it emphasizes is that the planting of stool pigeons by the police is an old device, having been used over a long period in frame-up labor cases. It was used in the Mooney, Imperial Valley, Centralia, and all other important labor cases. Therefore no one acquainted with police methods is surprised to find it used here. The program suggested is that mass protests be organized all over the country to back the legal defense for these miners. It is significant that mass protest is the only process that frightens the ruling class into freeing imprisoned and persecuted workers. The ruling class is afraid of mass protest, because it knows that behind such protest lies mass potentiality of a sort that has changed the course of history in more than one country.

Ignoring the pitiable plight of the miners as a whole, the Superior Colored Person naturally overlooks the Negro miners. I wish to broadcast the news that there are thousands of our race on strike in the regions named. I desire it known that wherever the miners have struck for more than starvation wages, decent housing, and conditions of living above those of beasts, the Negroes have struck with them. I desire to make it known that the black miners who await death in the electric chair feel a closer comradeship with their white fellow workers than they can possibly feel for the sleek-bellied members of the Colored Upper Crust; for their white fellow workers have stuck by them as a simple matter of course. The anti-Negro propaganda of the boss class has not turned the white toilers from the blacks, because they realize what in time certain other people will realize too late: that conflicts of this kind are class wars, not race wars. I wish to impress it upon High Society folks especially that while they are getting their names and the names of their latest models in cars into the society columns, thousands of their race are being forced to death by starvation, by exposure to the weather, and by the electric chair. I hope also that that section of the colored press which has benignly ignored the existence of these strikes will at least have compassion on naked and hungry black children and on innocent men charged with murder.

The Negro press could do a great deal if it would. It could (1) organize mass protests supporting those of the I.L.D. throughout the country among its readers; (2) inaugurate a cooperative scheme of raising money all over the country, a given newspaper in each section being assigned a quota; (3) interest the Negro ministry in the condemned men and the facts of their cases, as well as in the strikers and their cause; (4) give a lump sum to the Kentucky Defense Fund, c-o Inter- ntional Labor Defense, 80 E. 11th St., N.Y.C.

Then there are such celebrated Negro columnists and publicists as George S. Schuyler, Theophilous Lewis, Kelly Miller, Floyd Calvin, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Gordon Hancock (naming only a few at random); perhaps if they knew that thousands of miners are fighting starvation and that with the approach of winter their condition becomes inevitably worse–perhaps if these gentlemen knew about all this wretchedness and misery they might help in some way in their excellent columns.

Really, somebody ought to tell them about it. Of course, I know it is none of their business, but, unless my memory has gone back on me, neither was the breaking out of war in Europe in 1914 their business. Yet look what happened!

EDITOR’S NOTE: The Labor Defender is not in agreement with Eugene Gordon, when he writes that the oversight in the Negro papers concerning the Harlan and other strike struggles is due, to “disdainful aloofness (on the part of the editors) to all situations in which no Negroes are thought to be involved.” The reason for the rich Negro editors’ “neglect of the welfare of the very people they allegedly are most interested in the working class” is due chiefly to a class bias. It is the same reason why the New York Times editors are not interested in advancing the cause of strikers. Because both Negro and white capitalists are on the side of the ruling class.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Not only were these among the most successful campaigns by Communists, they were among the most important of the period and the urgency and activity is duly reflected in its pages. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1931/v07%286%29n11-nov-1931-LD.pdf