Pioneering Marxist film critic Harry Alan Potamkin looks at how the movie industry aided and addressed the First World War as cinema and its stars began to dominate the conveyance of a capitalist and imperialist world-view.

‘Movies and War’ by Harry A. Potamkin from New Masses. Vol. 8 No. 12. August, 1933.

THE film has served the war from its infancy. The American movie had its start in the Spanish-American War. Roumania used pictures of her troops in the Balkan war to stir enthusiasm for the World War. And Japan did the same with pictures of the Russo-Japanese War. In 1915, when we were ostensibly neutral, films like The Treason of Anatole were produced, sympathizing with French and German soldiery, but making of war a wistful attraction. That year England perpetrated films with a dual purpose: to stimulate enlistment, and to encourage Anglophile sentiment in America. An English producer said to an American journalist at that time:

“Our days — and nights — are spent in glorifying the British and showing the Germans up in an unfavorable light…American exhibitors have no desire to violate Uncle Sam’s admirable desire to be neutral.”

The tone, as well as sequence, is ironical. Fooling the Fatherland became, for American consumption, A Foreign Power Outwitted. “The explanatory matter of the play is to be so altered that it mentions either a nameless or fictitious power at war with Britain.” But — “for all our scheming we fail to cover up the fact that the enemy wear German uniforms, and a ‘doctored’ photoplay may always be detected by others.”

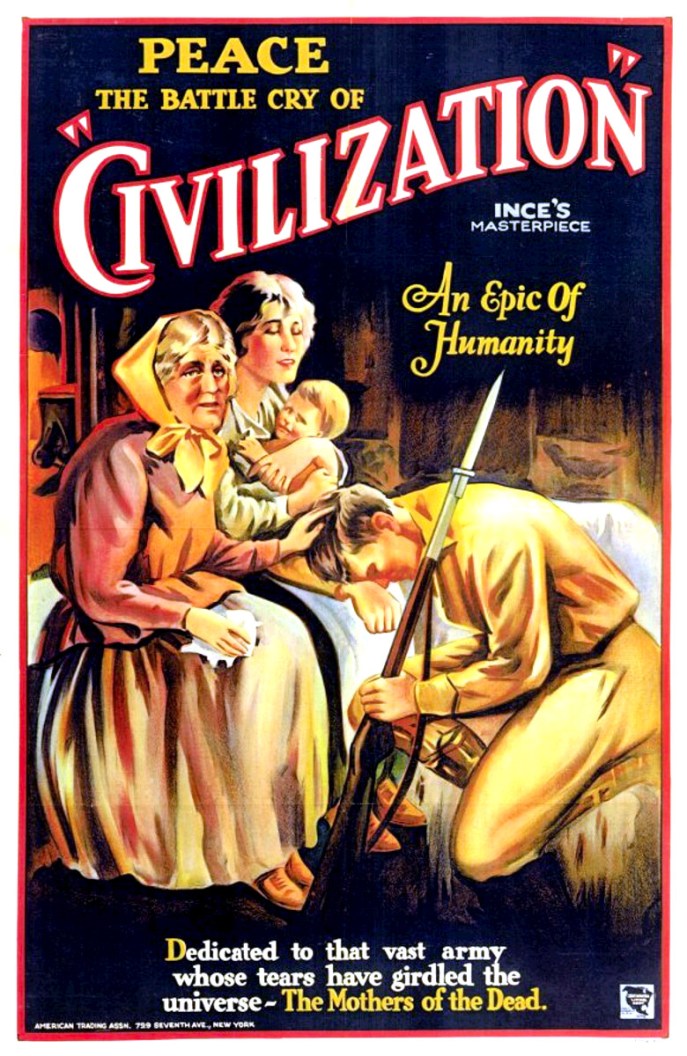

In September of 1915 Hudson Maxim’s preparedness tract, Defenseless Peace, was filmed as The Battle Cry of Peace. Ford attacked the picture in full-page newspaper ads. “He pointed out that Maxim munitions corporation stock was on the market.” Thomas Ince served the quasi-pacifist dish, Civilization, which strengthened Wilson’s campaign on the “Kept us out of war” ticket. The dubious pacifism of America produced War Brides, provoked by the acuteness of feminism at that moment. It told “how a woman, driven to desperation by the loss of loved ones, defied an empire.” Its romantic futility satisfied the uncritical pacifism that subscribed to, and was betrayed by, the Woodrovian slogans “too proud to fight,” “watchful waiting,” “he kept us out of war”. How simple it was to convert these into one glamorous “make the world safe for democracy!” War Brides was suppressed. The suppression was justified thus: “…the philosophy of this picture is so easily misunderstood by unthinking people that it has been found necessary to withdraw it from circulation for the duration of the war.”

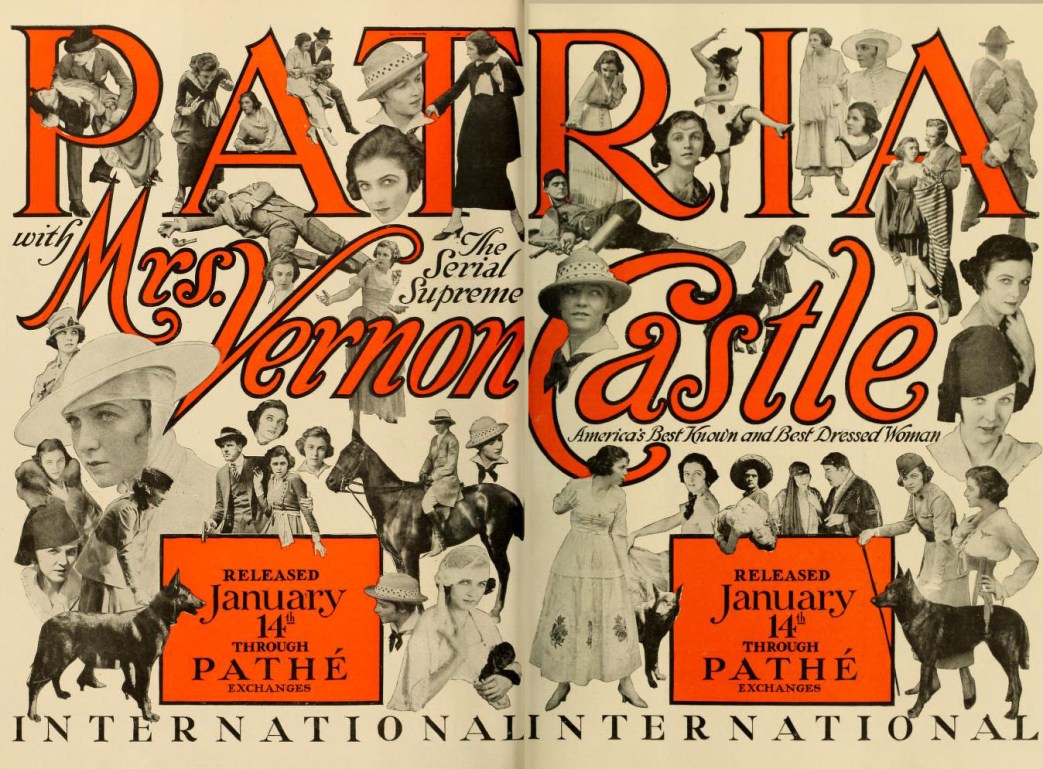

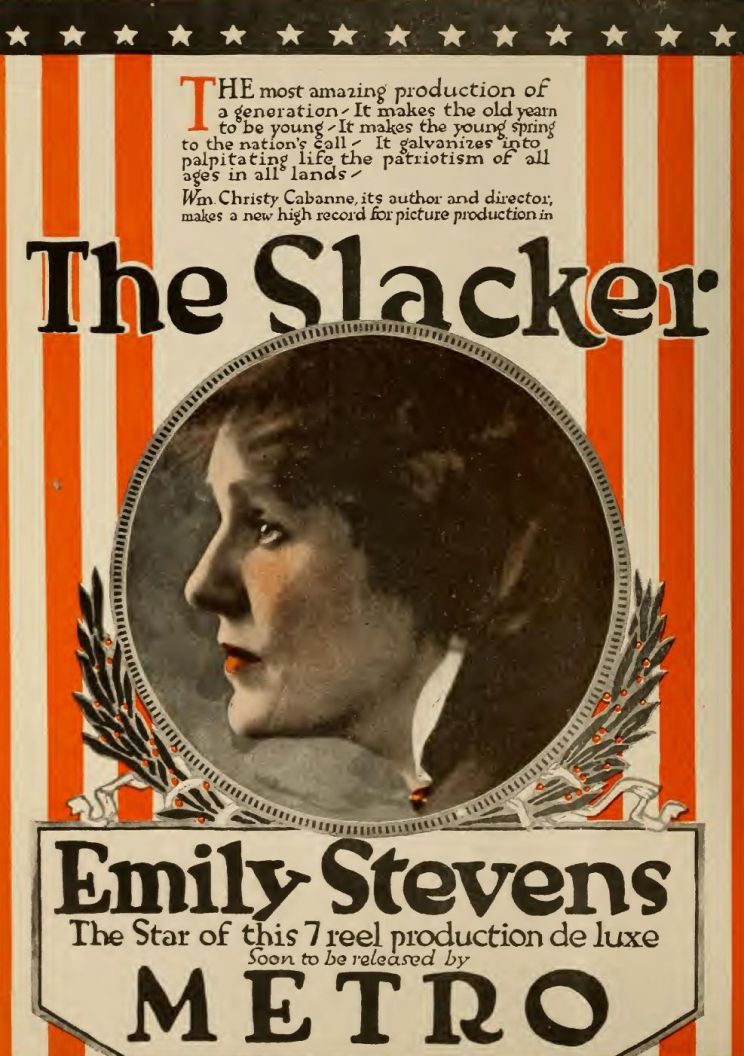

Hearst, more interested in Mexico and Japan than in Europe, took the serial, The Last of the Cannings, glorifying the Dupont family and American womanhood, and converted it into Patria, an attack on Hearst ’s phobias. We were not yet at war with Germany but close to it, and Japan was an ally of Britain, an enemy of Germany. Woodrow Wilson asked that the anti-Japanese touches be removed. The Japanese flag was lifted out, and, by contiguity, the Mexican too. Preparations for the war-objector were part of the preparedness propaganda. In the last months of 1916 The Slacker told of the conversion of a society butterfly into a flag-sycophant. It should be indicated also that the soldiers in War Brides, against whom Alla Nazimova rose, were out-and-out German.

Films appeared romanticizing British history and espionage: The Victoria Cross , the English in India; Shell 43, the heroism of a spy; An Enemy of the King, the days of Henry of Navarre. In 1914 the outdoor war-news film-showings of the New York Herald brought counter-applause from Allied and Entente sympathizers. “We were neutral with a vengeance in those days.” Germany tried to edge in for sympathy with Behind the German Lines. But the interests were concentrating popular interest upon the Allies, and pro-British, pro-French films appeared. Geraldine Farrar played in Joan the Woman, a Lasky picture. Pictures of our troops in Mexico, and the war abroad, had served to create an ennui for battle. The yearning was there, at first weak and confused, but steadily strengthened into violence by suggestion and direct hypodermic. The rape of Belgium was perpetrated in the studios of America, abetted by our Allies. An uninterrupted propaganda turned America about face, seemingly overnight. Actually this propaganda had been increasingly at work, ascending toward a climax, and America had turned quarter-bout, half-about, until full about, facing the Entente “squarely.” The need was to create and sustain a war-temper, to eliminate all doubts, and to extract devotion, moral and material.

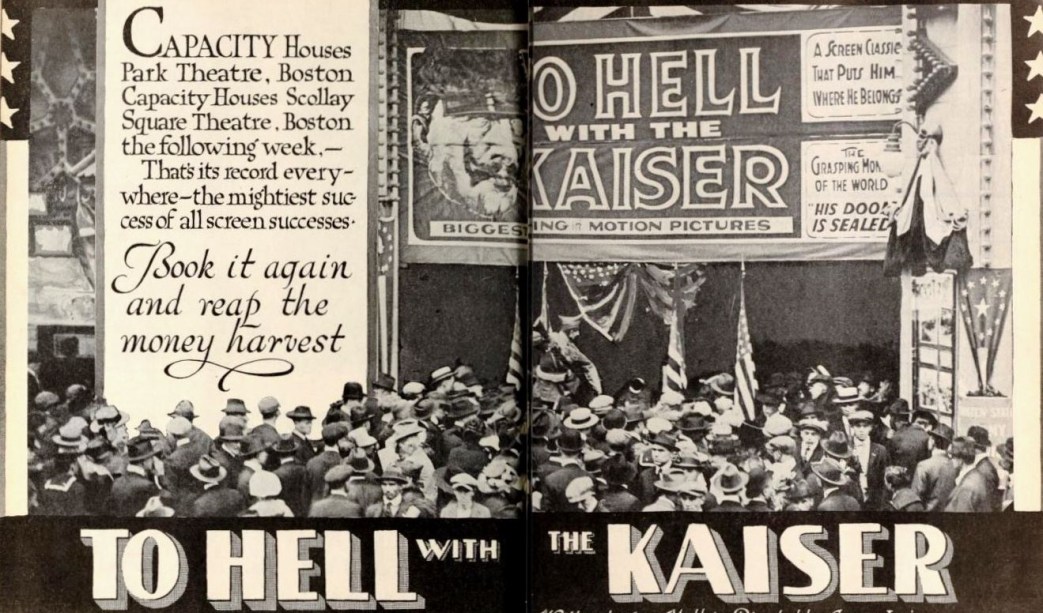

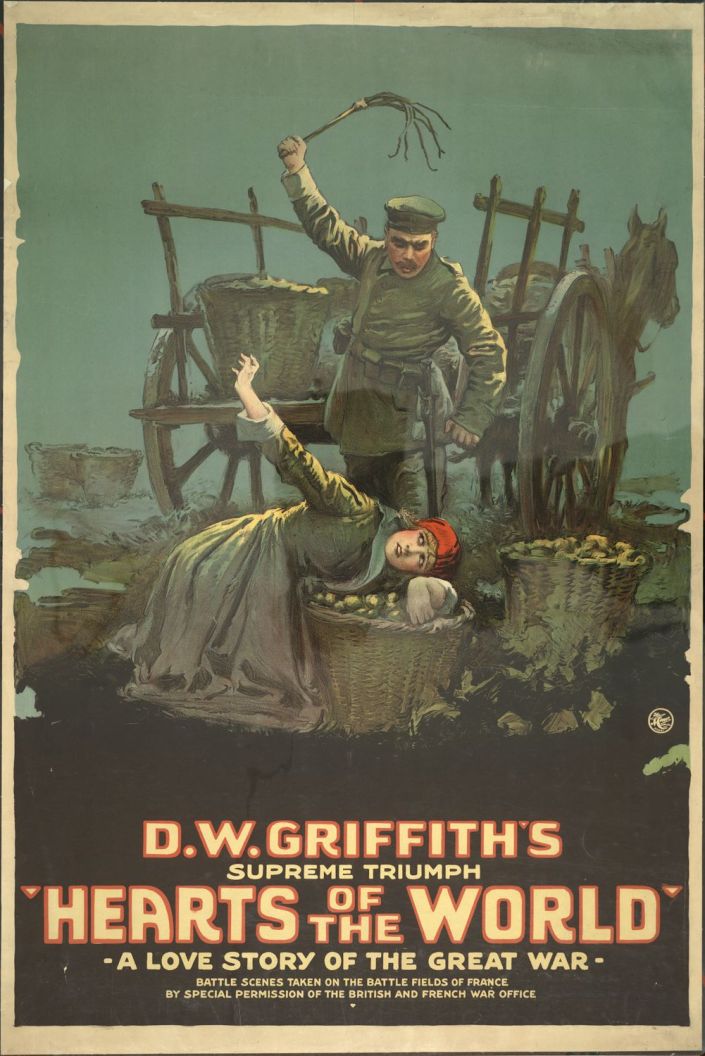

The impressionable directors set to. The Ince producers of Civilization emitted Vive la France. Slogan films were plentiful: Over There, To Hell With the Kaiser, For France, Lest We Forget. Love for our brothers-in-arms was instilled by films domestic and imported, such as: The Belgian, Daughter of France. Sarah Bernhardt in Mothers of France, Somewhere in France, Hearts of the World, D.W. Griffith’s contribution to the barrage. The strifes of France were presented to America: Birth of Democracy (French Revolution) and The Bugler of Algiers (1870). The vestiges of admiration for Germany were eliminated by films like The Kaiser Beast of Berlin, The Prussian Cur, The Hun Within. German-American support was bid for in Mary Pickford’s The Little American, a tragicomedy describing “the German Calvary of bestiality,” “the hell-hounds” and “the repentant Kaiserman.” Chaplin ridiculed the Kaiser in Shoulder Arms. The fair sex was intrigued by films like Joan of Plattsburg. As far back as 1916, “when everybody but the public knew we were going into the big fight overseas,” a glittering Joan on a white horse, contributed by the movie people, had paraded in the suffrage march on Fifth Avenue. The movie stars — like Mary Pickford and Dorothy Dalton — became the symbolic Joans of American divisions in the war. A miniature Joan, Baby Peggy, joined the abominable harangue that children spat on fathers of families: “Don’t be a slacker!” An insidious propaganda among children was instituted and developed. The “non-military” Boy Scouts had films made specially for them: Pershing’s Crusaders, The Star-Spangled Manner, The War Waif, Your Flag and My Flag, serials like The English Boy Scouts to the Rescue, Ten Adventures of a Boy Scout. The objector was shamed by “don’t bite the hand that’s feeding you” movies: My Own United States, A Call to Arms (The Son of Democracy), The Man Without a Country, Draft 258, The Unbeliever, The Great Love, One More American, The Man Who Was Afraid. German atrocities were insisted upon: The Woman the Germans Shot. All branches of the service were gilded: The Hero of Submarine D2.

Governmental organization found incentive in conjunction with England, citizen bodies and film corporations. An American Cinema Commission went abroad. England had organized one with eminent individuals like Conan Doyle. D.W. Griffith not only was at work in England on Hearts of the World, but he also cooperated with high society in recruiting British sentiment. The National Association of the Motion Picture Industry, William A. Brady president, was organized but never functioned, although it served as a stimulant to the movie companies’ enthusiasm. The Red Cross had begun to use films but not satisfactorily enough. With Creel’s Committee on Public Information, the Red Cross set up the Division of Pictures, which released four films to one-third of the movie houses, “about the same number of audiences as Chaplin audiences.” In New York there was the Mayor’s Committee of National Defense, Jesse L. Lasky, motion picture chairman. The movie companies organized a War Cooperative Council. In 1918 the films were said to have put about $100,000,000 into the war chest. Movie stars spoke and carried on for the Red Cross, the Liberty Loan and enlistment. A propaganda slide in the cinemas read: “If you are an American, you should be proud to say so.” The sale of Liberty Loan bonds was helped by 70,000 slides. Douglas Fairbanks jumped from a roof for $100 for the Red Cross, and Chaplin sold autographed halves of his hat. The movie-actors joined the California Coast Artillery, others organized the Lasky Home Guards. Lasky received a title for his work in many divisions. His cooperation with the Government was balanced after the war by the Government’s willingness to help in the aviation film, Whigs. The popular star, Robert Warwick, now a Captain, was quoted in the fan-press upon war’s ennobling qualities.

The period since the war resembles in a general way the period before and during the war. There are films like The Big Parade and even All Quiet on the Western Front which explicitly condemn war, but implicitly, by their nostalgic tone, their uncritical non-incisive pacifism, their placing of the blame on the lesser individual and the stay-at-home, their sympathy with the protagonist, their excitement, their comic interludes, make was interesting. Their little condemnations are lost amid the overwhelming pile of films in which war is a farcical holiday, or a swashbuckler’s adventure. The momentary pointing of guilt is made so naive, so passing that it never gets across to the audience — The Case of Sergeant Grischa and Hell’s Angels. It simply serves as a betrayal supporting the bluff of disarmament conference.

Carl Laemmle was suggested for the Nobel peace prize for All Quiet. During the war he made The Kaiser Beast of Berlin, after the war he wept over the plight of his “Vaterland” in his advertising column in the Saturday Evening Post, and after All Quiet he issued series of sergeant-private-girl farces in which one of the agonized Germans of All Quiet is starred. Well, he still qualifies for the prize; he is no less noble than Wilson or Grey.

We have also governmental cooperation. The Navy, however, has declined to cooperate in films kidding officers. It’s all right to make fools of gobs, but it’s bad business to invite gobs to laugh at the officers. The class-distinction is important in the capitalist army, more and more important today. Further cooperation between producer and military is found in the Warner Brothers’ instruction in sound to officers. The battleships are being sound-equipped. How easily the movie can be put on a war-basis! And, of course, we still have the films glorifying individual branches of the service, from diving to aviation. Film producers and impresarios carry honorary military titles.

Let us not be led astray by objections to pacifist films like All Quiet and Hell’s Angels. The neurosis of “national honor” is today so active that the slightest abrasion sets it off. The fascist Germans find in these films insults to German officers. The fascist French accept them for the same reason. In the meantime, Germany issues a film like The German Mother Heart, in which a mother who has lost six sons is made to feel how exceptional was her opportunity. In America a similar theme is handled in Four Sons. And with it all we have “educational” films flaunting patriotism; R.K.O. has a Patriotic Week that is praised by Vice-President Curtis…the total is rather threatening.

War is completely indicted in the films of the U.S.S.R. alone.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1933/v08n12-aug-1933-Mew-Masses.pdf