Jeannette D. Pearl, one of the founding women of U.S. Communism, writes among the first articles in the Communist press looking specifically at the position of Black women. Joining industry in large numbers for the first time during World War One, Black women, ‘the last hired and first fired,’ saw a post-war contraction of opportunity even as more Black women were moving to the industrial north and joining the labor force.

‘Negro Women Workers’ by Jeannette D. Pear from the Daily Worker Saturday Supplement. Vol. 1 No. 341. February 16, 1924.

NEGRO women who entered industry during the war are fast learning that their lot is still “the last to be hired and the first to be fired.” According to a report just issued by the Woman’s Bureau at Washington on the “Negro Women in Industry,” a great number of Negro women are being eliminated from industry and those remaining are most ruthlessly exploited. Their hours of toil range all the way from eight to sixteen hours a day and sometimes longer; their pay is miserably small and the conditions under which they work are most brutal.

The report covers a survey of 150 industries employing 11,860 Negro women. The purpose of the investigation was made in order to create a better understanding and greater sympathy among employers of Negro women with the aim of thereby raising the standard of living.

This humanitarian aspiration is strongly coupled with repeated emphasis upon the fact that a higher standard of living will yield increased production.

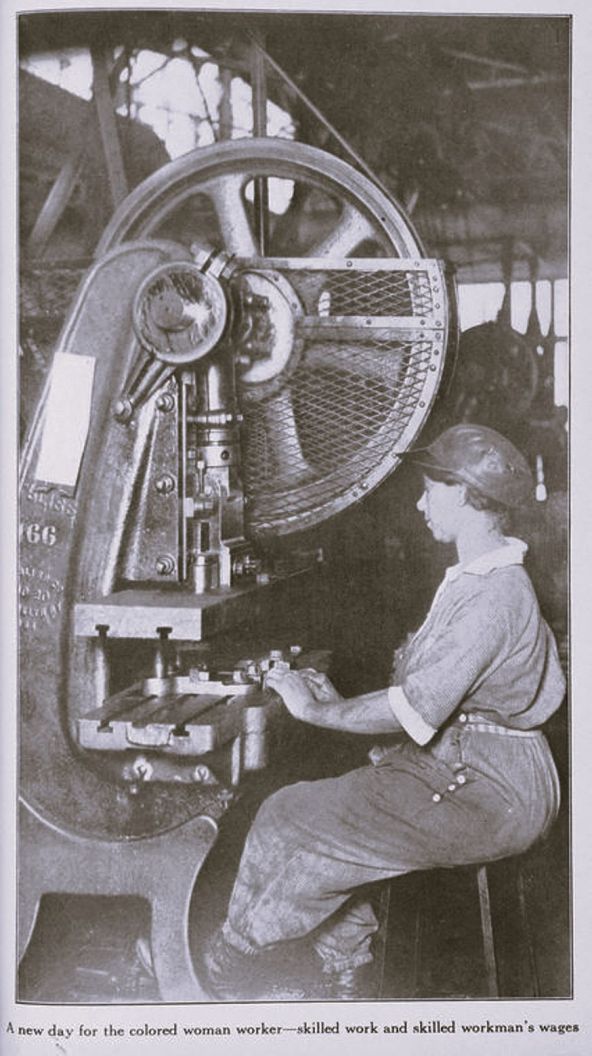

Negro women found their OPPORTUNITY in industry during the world slaughter when the need for munitions of war created a labor shortage in the labor market. The five chief industries that women entered were textiles, clothing, food, tobacco and hand and footwear. The Negro women in the main filled the gap caused by the advancement of white women into newer and more skilled occupations.

Thirty-two and five-tenths per cent of the 11,860 Negro women investigated were working ten hours a day and over; 27.4 per cent were working nine hours a day, and 20.2 per cent were working eight hours a day. These figures do not tell all of the story. Overtime can and does follow the legal work day. Overtime “is permitted as much as desired.” The report tells how workers boast of their thriftiness in beginning work, “before hours, after hours, and working during lunch hour.” One worker puts it, “You just can’t make ends meet unless you do extra work and often you are left in a hole even at that.”

A typical case is cited indicating how these Negro women live for the most part. Rise at five, cook breakfast, dress children, prepare food and attend to things about the house, report for work at 7, leave at 5:30, resume housework on returning home, frequently continuing this work until midnight, dead tired as a result.

One woman worker states “I am so tired when I reach home I can scarcely stand up. My nerves are so bad, I jump in my sleep.” Another woman complains, “I’d love to go to the Y.W.C.A., but I am so tired at night, I can scarcely go to bed. If I go out at night, I go where there is lots of life and lots of fun; I’d go to sleep at a lecture or club meeting.” Another case cited, “I am so worried and worn in my strength that I feel at times as if I can stand it no longer. It is not alone the need of money but the responsibility of being nurse, housekeeper and wage earner at one time.”

The average pay of the Negro women in industry is about ten dollars a week. The minimum wage is calculated at $16.50. When it is taken into consideration that many of these women have dependents and are sometimes the sole supporters of their families, one wonders whether slavery days before the civil war could have been much worse.

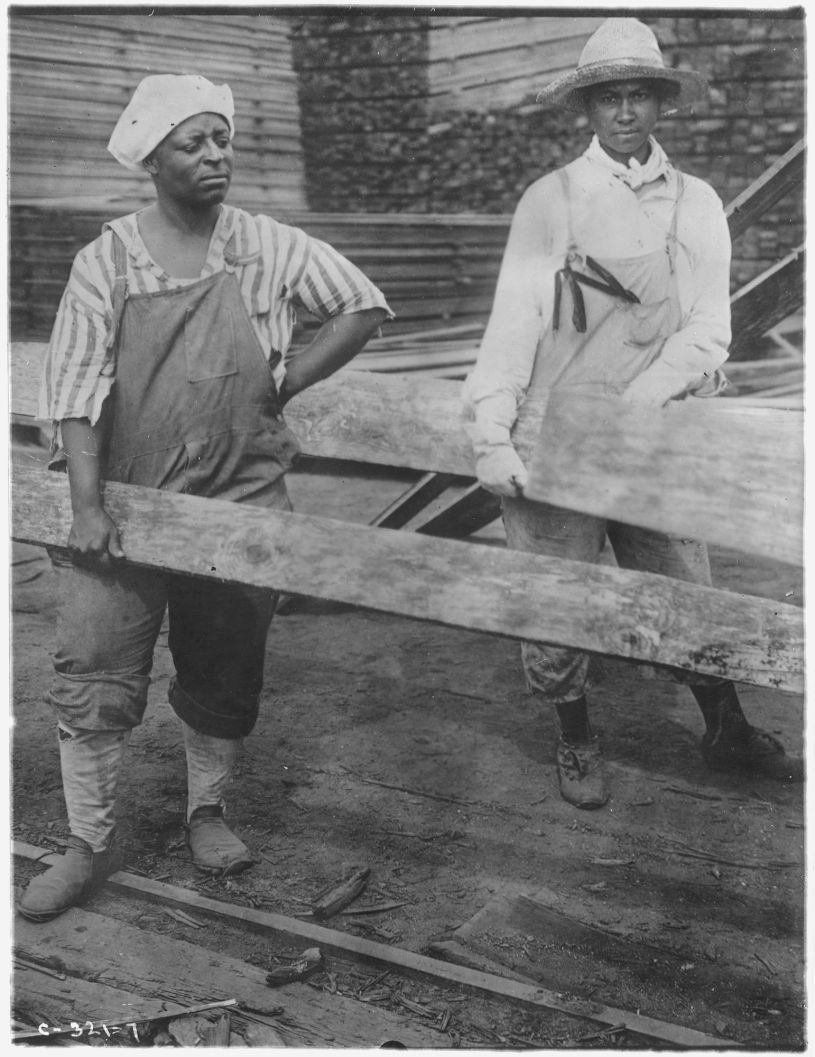

The frightful conditions under which most of the Negro women work add to the horror of their wretched pay. They are often segregated because of race prejudice, given inferior and harder work and because of their “ignorance” they are shamelessly cheated, false computation of wages, scales wrong, count wrong, etc. At the end of the week “you never know what you are going to get; you just take what they give you and go.” The report points out that there is a strong feeling among Negro women workers that they are not getting a square deal.

Since the Negro women are unorganized they accept the most outrageous conditions of employment. They are not alone discriminated against because of their color and often segregated, but they are made to work amidst conditions the United States government would not permit its hogs to live under. Herded together in terrible congestion, in filth, feted dust-laden, poisonous air, poorly ventilated, still more poorly lighted, these women work and often have to eat in the same atmosphere.

The report points out, “Confronted with the need for food, clothing and shelter and placed in an environment which was unhealthful and sometimes even degrading, they were seen to have lost themselves in the struggle for bare existence.”

The treatment accorded most of these workers is well expressed in the words of one of the managers, “They are terribly indolent, careless and stubborn, but we know HOW to handle them. We give them rough treatment and that quells them for a while.” Yet another manager observes, “You never saw a group of people so responsive to kindness? In the main, these women are conscious of their industrial experience and showed timidity which was a draw- back in acquiring assurance and speed so necessary in factory production. Their patient trust and belief in the better day that should come to them as workers is pathetic.”

The report points out that bad working conditions and long hours are a serious menace to the state, that the prosperity of a nation is endangered when its workers are being crippled with exhaustive labor. Loss of human energy, due to excessive working hours becomes a national loss and is bound to lessen the nation’s productive yield. The reporter, therefore, recommends legislation for a higher standard of living, inasmuch as a higher standard of living will produce greater efficiency in production and greater profits.

The report would have self-enlightened employers and the State jointly work out an appropriate “award” as compensation for Negro women in the industries. It would be a sort of benevolent industrialism for greater efficiency and greater national progress-for the master class.

To that end is also recommended, “A more conscientious training for efficiency in public schools, thru fostering of pride in achievement, increasing personal and family thrift, and encouraging of constancy toward a given task, would ensure that ‘preparation for life’ which is the purpose of all education.”

Against such “purposes” in education must be posed the Communist method of education, thru labor solidarity making for self-reliance and self-development. Not a “pathetic” longing for a better day, but a resolute expression in action for a better day will result from Communist education.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1924/v01-n341-supplement-feb-16-1924-DW-LOC.pdf