Gorky’s unique take on the situation the Soviets found themselves in at the end of the Civil War as the relationship of the new Workers’ State to the peasant majority dominated all discussions and decisions. Gorky sees two cultures; the city to which he is drawn and sees the future in, and village whose traditions he is repelled by.

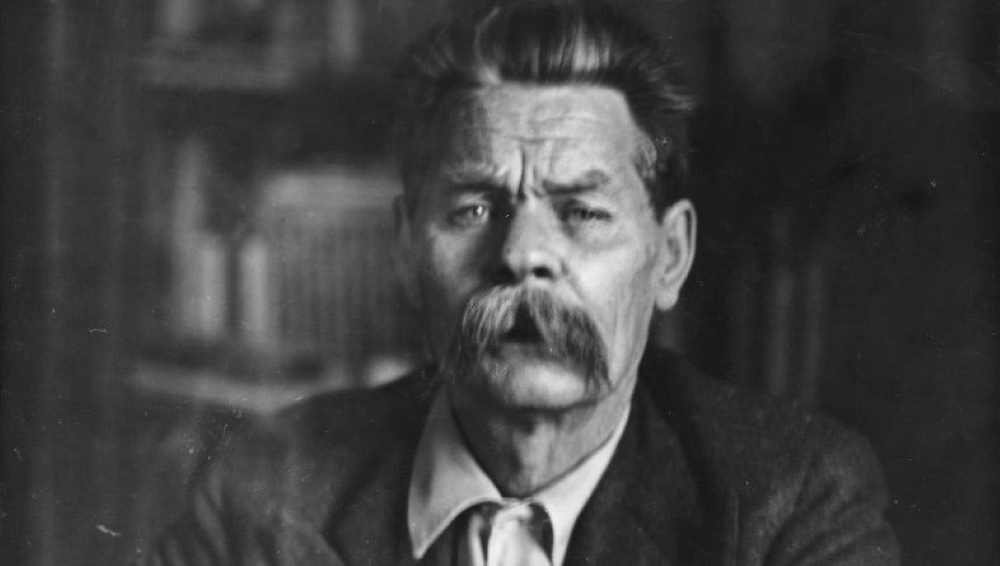

‘Two Cultures’ by Maxim Gorky from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 2 No. 23. June 5, 1920.

Always and everywhere history has developed the man of the village and that of the city as two psychologically distinct types. The difference is becoming greater and greater, as the city rushes ahead with the speed of Achilles, and the village trots along with that of a turtle.

The rural dweller is a being, who from the very first days of spring and until late in autumn makes grain to sell the greater part of it, and to consume the smaller part of it during the accursed, mercilessly cold winter.

No doubt the “living gold of the rich fields” is very beautiful in summer, but in the fall, instead of gold, the shabby naked ground remains, which again calls for hard labor and again unproductively sucks out valuable human energy.

This man—the whole of him—inwardly as well as outwardly—is a slave to the powers of nature; he does not struggle against them—he merely adapts himself to them. The ephemeral results of his labor do not and cannot inspire in him self-respect and confidence in his creative abilities. Of all his labors there remain on earth only straw and a dark, crowded, straw-covered hut.

The work of the peasant is extremely hard, and this burden combined with the poor results obtained from his labor, naturally implant in his heart a dark sense of ownership, making him almost immovable. This instinct is almost immune to all teachings which consider that the first man’s sin lies in this very instinct of private property, and not in the joke played on foolish Adam by the Devil and by Eve.

When one speaks of bourgeois culture, I think of village culture—if it is possible to combine these two words, culture and village; in the spiritual sense these two words cannot be combined. Culture is the process of creation of thought, the embodiment of these in the form of books, machines, scientific instruments, paintings, structures, monuments, in various objects which present the crystallization of ideas, act as an inspiration for other ideas, and, increasing in quantity, encircle the entire world endeavoring to discover the most mysterious causes of all its phases.

The village does not create such culture and in general it does not erect monuments other than songs and proverbs. Yes, indeed sad is the melancholy song of the village. Its sorrowful lyric, it seems, can soften rocks. But rocks are not softened by songs, neither are people. Indisputably the village has much sad poetry and it lures us on to the path of erroneous sensitiveness, but immeasurably more significant in substance as well as in volume is the prose of the village, its animal epic prose which is still in existence. The village idylls are hardly noticeable in the continuous drama of the peasant’s everyday life.

In comparison with the passive, half-dead psychique of the old village the urban bourgeoisie is, at a certain stage the most valuable creative incentive; it is that strong acid which is fully capable of dissolving the peasant’s iron soul, which is soft in appearance only. The inertness of the village can only be conquered by knowledge and by the introduction of a large socialistic economy. It is necessary to have an enormous amount of agricultural machines; they and they only will convince the peasant that private ownership is a chain by which he is bound; that it is spiritually disadvantageous for him; that unintelligent labor is unproductive and that a mind disciplined by knowledge and ennobled by art will be an honest guide on the path of liberty and happiness.

The labor of the city dweller is fabulously variable, monotonous and eternal. Out of bits of earth, turned into bricks, the city dweller builds palaces and temples; out of shapeless chunks of iron ore he creates machines of surprising complexity. He has already subordinated natural energies to his lofty aims and they serve him as the Djins in oriental tales served the sage who enslaved them by the power of his wisdom. The city dweller surrounds himself with an atmosphere of wisdom. He always sees his will embodied in a variety of wonderful things, in thousands of books, pictures in which by word and brush have been impressed during the centuries the majestic tortures of his inquisitive spirit, his dreams and hopes, his love and hatred—his entire immense soul, which is always thirsty for new ideas, deeds, forms.

Although he is enslaved by state politics, yet the city dweller is innately free, and by force of this spiritual freedom he destroys and creates forms of social life.

Being a man of deeds—he has created for himself a painfully tense, sinful, but beautiful life. He is the instigator of all social ills, perversions; he is the creator of tyranny, falsehood and hypocrisy; but it is also he who has created that microscope which permits him to see with such a painful clearness the most minute movements of his ever-discontented spirit. He has brought up in his spheres magicians of science, art and technique— magicians and sages, who indefatigably work for strengthening and developing these foundations of culture.

He is a great sinner before his kind, but probably a still greater sinner towards himself! He is a martyr to his aspirations, which, destroying him, give birth to new joys and new pains of being.

His spirit—the accursed Ahasuerus—marches and marches into the fathomless future, somewhere towards the heart of Cosmos, or into the emptiness of the universe, which he is perhaps called upon to fill by exerting his energy in the creation of something which is beyond the imagination of the present day mind.

For the intellect the development of culture is important for its own sake, irrespective of the results; the intellect in itself is first of all a phenomenon of culture; the most complex mysterious product of nature, its organ of self-knowledge.

Of greatest importance to the instincts are the utilitarian results of culture, even those which help the outward welfare of being, though this may be a miserable falsehood.

Therefore, at present, when the excited instincts of the village must inevitably enter into a struggle with the power of the city, when the city culture—this fruit of centuries of activity of the intellect, which includes the factory worker, —is in danger of destruction and of being delayed in the process of development, the intellectuals must revise their attitude towards the village.

There is no people—there are only classes. The working class has been so far the creator of material values alone, but now he wants to take active part in spiritual and intellectual work. The majority of the rural masses aspire to strengthen by all means their position of land-owners—they do not state any other desires.

The intellectuals of the world, of all lands are faced by one and the same problem—to devote their energy to that class, whose psychic peculiarities assure further development of the process of culture and are fully capable of increasing the speed of progress.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v1v2-soviet-russia-Jan-June-1920.pdf