From a speech delivered to the Volksmarinedivision of rebellious sailors on November 23, 1918 during the German Revolution.

‘Proletarian Revolution and Proletarian Dictatorship’ (1918) by Karl Liebknecht from Voices of Revolt No. 4. International Publishers, New York. 1927.

Comrades, friends! You know how those few persons that dared express themselves publicly in opposition, were calumniated and menaced in that period of mass hysteria. Not a day passed on which I was not the recipient of the most savage imprecations and insults. Little by little, an increasing section of the population began to recognize the — correctness of our position, and now we are lauded and praised. But this merit is, indeed, not our own, for a considerable number of plain working men remained steadfast from the very outset, in spite of the war mania. It was this section which supported us and this section which deserves all the praise.

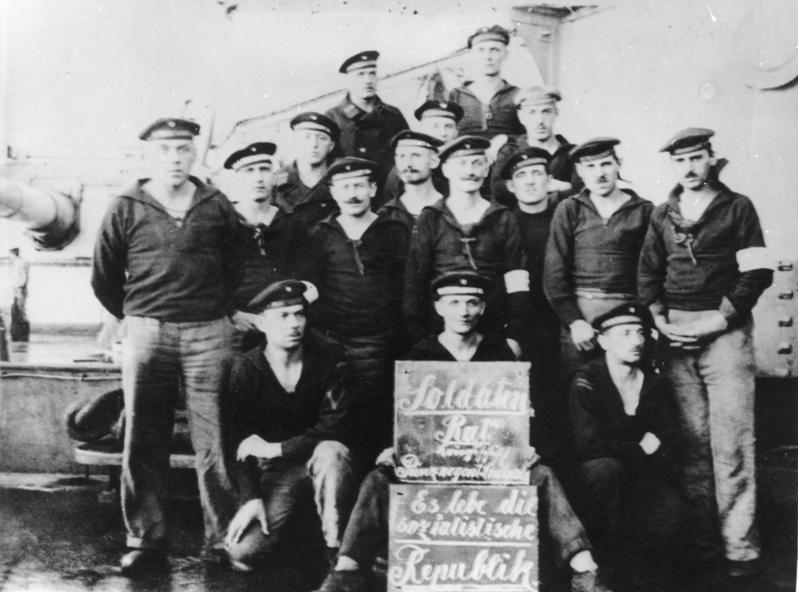

What is the nature of this revolution? It is in great part a military insurrection directed specifically against war. It was kindled directly by the fears of the sailors that the Admiralty might continue the war of its own authority after the collapse of the land fronts.

There developed from this the mutinies of the troops stationed in the interior of Germany. The working classes have for a long time been pressing forward stormily. Even bourgeois circles have cooperated within and without the army, but these are very undependable, very suspicious elements. The soldiers must not forget how important is the part played by the workers. The troops at the front were not actively engaged in the revolution.

What is the basis of power of the present revolution? We must first ask, what revolution do we mean? For the present revolution has a number of very different contents and possibilities. It may continue to remain what it has been thus far: a reform movement in favor of peace, a bourgeois movement. Or it may become what it has not been thus far—a proletarian Socialist revolution. The proletariat will, even in the former instance, have to furnish the most important prop, unless the revolution is to be degraded into a farce. But the proletariat cannot content itself with this bourgeois-revolutionist content. Unless all the achievements that have been made thus far shall again be lost, it must march on to the social revolution: the day of settlement between capital and labor. This turning point of the world’s history has arrived.

Has the proletariat the power in its hands today? Workers’ and soldiers’ councils have been formed, but they are by no means the expression of a fully clear proletarian class consciousness. Their members include officers, many of them of noble birth. The workers’ councils include members of the ruling classes; this is disgraceful. Only workers and proletarian soldiers, or those men and women who have distinguished themselves by a life of self-sacrifice and struggle for the proletariat, should be elected to the workers’ and soldiers’ councils. No others must be put into responsible posts at this time. This obvious assertion of authority must be made to the ruling classes, who have imposed their will upon the proletariat for so long a time. Only the proletariat itself can liberate itself…The composition of the councils up to this time lays bare the root of the evil, namely, the masses of the workers and soldiers are not yet sufficiently enlightened either politically or socially.

Do the workers’ and soldiers’ councils at present really hold the political power? Not only the economic and social positions of authority, but many of the positions of political authority have continued to remain in the hands of the ruling classes. And what they had lost of these positions they have again succeeded in recovering with the aid of the present Government; the officers have again been restored to their commands, the old bureaucracy has again assumed its functions—under supervision, to be sure, but under a supervision whose effectiveness is necessarily more than dubious, for the supervising proletarian is often circumvented by the may, bourgeois in the turn of a hand.

The social position of authority held by the higher education possessed by the ruling classes was a source of great defect also to our comrades in Russia. Members of the ruling classes are for the present in many cases indispensable as auxiliaries and specialists. They are obliged to put themselves in the service of the Revolution; but to intrust them with power would mean a serious jeopardizing of the Revolution.

Now the Generals are returning from the front to the interior with their huge armies. They deport themselves like Caesars at the head of their legions, forbid the raising of the red flag, abolish the soldiers’ councils, etc. We may expect many acts on their part, possibly even an attempt to bless us once more with the noble Hohenzollern dynasty. If these huge armies were permeated with a revolutionary spirit, they could not be abused in the infamous manner in which they are now being abused. But the first and foremost duty of the “Socialist”? Government is to disseminate this spirit among the troops at the front, a duty this Government has basely neglected, waving the red flags zealously instead, and sowing hatred against “Bolshevism,” and thus handing over the masses of the soldiers the more defenselessly to the mortal enemies of the Revolution—the military officers—whom this Government had itself restored to their commands. The ingenious plan that is being pursued is that of flooding Germany with a new counter-revolutionary danger by means of the troops from the front, who, as a result of the armistice conditions and its consequences, are again imbued with chauvinistic spirit. This plan must be opposed ruthlessly, the Generals must at once be eliminated, the authority to give commands abolished, all the armies organized democratically from the bottom up. We are told this is impossible because of the difficulties of demobilization. Far from it! Let us have confidence in the revolutionary self-discipline of the German soldier masses. Once they are fired with the enthusiasm of revolutionary zeal, they will solve with ease practical problems that seem impossible of solution in normal times. Faith can move mountains; where there is a will, there is a way. But, first of all, I ask: Is a proper retirement of the German troops more important than the Revolution? Is it not outright madness to hand over to the mortal enemies of the Revolution—for the sake of “order” and “‘peace”—-means of power capable of menacing the very existence of the Revolution? However we may regard the question: the restoration of the power of command was an ax-stroke into the heartwood of the Revolution. It is to this step that we owe chiefly the loss of the achievements of the Revolution of November 8 (1918), for the power which the proletariat swiftly secured on that day: has for the most part returned to the hands of the ruling classes.

We may now ask: What is now to be done? What is the duty of the proletariat in this situation? | It cannot be the duty of the proletariat to conclude with the foreign imperialists a peace that is unworthy of them as men, a throttling peace. Such a peace is not only intolerable, but it is a momentary peace only, necessarily productive of new wars. The goal of the proletariat must be a peace of well-being and freedom for all nations, a permanent peace. But such a peace can be based only on the revolutionary will, on the victorious acts of the international proletariat, on the social revolution.

Can the proletariat content itself with merely eliminating the Hohenzollerns? Never! Its goal is the abolition of class rule, of exploitation and oppression, the establishment of Socialism. Our present Government calls itself Socialist. Thus far it has acted only for the preservation of capitalist private property. The Socialization Commission appointed by this Government, which to this day has not once met, is in all its membership a commission to oppose and retard socialization. And yet we need quick and energetic action, not delay. To be sure, the socialization of society is a long and toilsome process, but the first emphatic steps can be taken | at once. The Government should have taken them in the very first days of the Revolution, instead of which it has not yet gone so far as to confiscate the crown lands of the potentates. The large-scale industries have long been mature for expropriation; the Reichstag was already about to nationalize the armament industries in 1913. The military-economic measures of the last four years have shown how swiftly it is possible to introduce serious changes in the economic structure, and yet there was no change, no capitalist disorganization, as a result. The military economy offers technically very useful suggestions in connection with socialization.

There must be no timid hesitation, we must take a firm hand here also. Here also, this will be the best way to overcome all difficulties.

The ruling class is not thinking of giving up its class rule. They can be put down only in the class struggle. And this class struggle will and must pass over the bodies of all governments that do not dare take up the struggle with capitalism, and preach instead to the workers—day by day—peace, order, the wickedness of strikes.

The extermination of capitalism, the establishment of the Socialist order of society, is possible only on an international scale—but, of course, it cannot be carried out at a uniform pace in all countries. The work has begun in Russia, it must be continued in Germany, it will be completed in the Entente powers.

Only the path of social world revolution can lead us out from the terrible dangers. which threaten Germany by reason of the food and raw materials situation. Nor does the German proletariat build its hopes in this connection on Wilsonian promises of mercy, but on the rock of the international proletarian solidarity.

There are two alternatives for liquidating the war —the capitalist-imperialist alternative, and the proletarian-Socialist alternative.

The former will afford for a moment a peace unworthy of men, a peace that will give birth to new wars. The second offers a peace of well-being and permanence. The former will preserve the capitalist order of society; the second will destroy it and liberate the proletariat.

The German working class to-day has the power in its hands, or at least it has the strength to seize and hold this power.

Shall it give up this power; shall it bend the knee before Wilson; shall it capitulate at the command of hostile imperialists to its mortal enemies within the country, to the German capitalists, in order to be given a hangman’s peace? Or shall it not rather— as we demand—oppose with equal ruthlessness the imperialism within the country—in order thus to attain a proletarian Socialist peace!

What proletarians, what Socialists, can find this peace so difficult? The social revolution must come in Germany, and from it must come the social world revolution of the proletariat against world imperialism. This is the only solution also for all the urgent and terrible individual problems which face the German people to-day.

One must grasp the full compass of the capitalist world with its far horizons and perspectives to-day, in order to recognize the folly of all doubts as to the possibility of these goals. Those are the doubts under which is hidden the petty spirit of an opportunist ward politics.

The Navy has done great things in this Revolution, and will do even greater things if it pursues the course it has begun, and refuses to permit itself to be influenced by the lies that are being circulated concerning Bolshevism, etc.! Do not forget how we were persecuted before, and how we turned out to be right in the end. The more enemies we have, the more honor shall we win!

I admit that only enthusiastic zeal can achieve great results. We need conviction and confidence; we need clearness as to means and ends. Shall we recoil from our task because it.is a difficult one? We behold the shining star which indicates our course; the sea is dark, stormy and full of reefs. Shall we give up the goal for this? We shall keep our eyes open and avoid the shoals—and shall steer our course—and shall reach our goal—in spite of everything!

Speeches of Karl Liebknecht. Voices of Revolt No. 4. International Publishers, New York. 1927.

The fourth in the Voices of Revolt series begun by the Communist Party’s International Publishers under the direction of Alexander Trachtenberg in 1927.

PDF of original book: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/voices-of-revolt/04-Karl-Liebknecht-VOR-ocr.pdf