A fantastic essay by the veteran Marxist on the history, culture, and politics of the British workers’ movement.

‘The British Labor Movement’ by Theodore Rothstein from New Review. Vol. 2 No. 1. January, 1914.

Since 1910 the British working class has again taken a position in the front ranks of the labor movement of the world. The British workman is now a very much discussed person, and recent events in Ireland, with their repercussion on the struggle in England, have detracted nothing from the interest which he inspires alike in friend and foe. What in the world is he after? This seems to be the question anxiously asked by the capitalist as well as by his own brother in foreign countries. Is he just fooling, or does he really mean business? Is he merely revolting against temporary disadvantages, or is he bent upon doing permanent mischief? In short, what is the meaning of this unrest in the British labor world?

The question would never have been asked if the British workman had not been known for two generations as a person totally different from what he appears to-day. Was he not the best-behaved workman in the world? Read the numerous books in various languages that were written about him in the past: was he not always represented to be a paragon of virtue–an industrious, patient, level-headed, practical and responsible man of labor? And is this not borne out by statistics showing how seldom he quarreled with his employers, how readily he negotiated with them for amicable agreements, how faithfully he observed the contracts, how promptly he accepted conciliation and arbitration, and how obediently he followed his chosen leaders? He was, indeed, the model workman of the world the delight of social reformers and the despair of the Socialists. Who does not remember his behavior at international congresses where he would smilingly watch the childish excitement of the foreign delegates and lecture them upon their lack of practical common sense? Alas, this type of workman has now disappeared! A younger generation has arisen which simply delights in picking quarrels with employers, and speaks in terms of “general” and “sympathetic” strikes. No wonder people are rubbing their eyes and asking in amazement: what has happened?

Something, indeed, has happened a trifling thing, hardly worthy of mention. The cost of living has risen–nothing more. But this trifling circumstance has opened the eyes of the British workman-thence “all his qualities,” as Tolstoy would say.

The type of British workman with which we were familiar until recently was formed during the counter-revolutionary era which followed the collapse of the Chartist movement. Politics and revolutionary methods of warfare were discredited, and a profound sense of disappointment and helplessness pervaded the ranks of the working class. What were the people to do? The more energetic among them fled the country and helped to swell the tide of emigration to the colonies and America. The others, with stupid resignation and despair, turned to their every-day tasks. “Suffer, such is thy lot”-this seemed to be their predominant feeling. But on the very day, April 10, 1848, which registered the collapse of the old hopes at Kennington Green, a group of “Christian Socialists” assembled in the house of F. Maurice and came to the conclusion that something more than military force was required to oppose the Chartist infatuation. About the same time the Earl of Shaftesbury, on the strength of his experience with the movement for the Ten Hours’ day, advised the Prince Consort to put himself at the head of social reforms if he wished to kill the revolutionary spirit in the country. The mood and the behavior of the working class after the collapse of 1848 suggested to the reformers the lines on which they had to work. Emigration? Why, this is far from being a calamity! Emigration, Maurice declared, was the holiest thing that could be imagined. As for the tasks of everyday life, these are just the things which form the essence of “Christian” existence. And with the help of some of the mightiest in the land emigration funds were started, co-operative societies were formed, workingmen’s colleges were established, and here and there even trade unions were called into life to assist the workman in his struggle for better conditions of labor. Down with despair, was the watchword-down with despair over the collapse of utopian and un-Christian hopes! Let us work in the present and for the present! And simultaneously the capitalist classes were appealed to for generosity and justice, and Parliament was called upon to do its share of reform work.

Strange to say, the appeals succeeded. They coincided with the opening of that grand era of capitalist expansion which began after the abolition of the Corn Laws. England was rapidly becoming the workshop of the world, and immense wealth began to flow into the coffers of the English bourgeoisie. Not daring to rely too much on armed force which, in the absence of militarism, was inadequate, and reaping at the same time a fabulous harvest of profits in every part of the globe, the English capitalist classes saw the wisdom of responding to the appeals of the “social reformers” and adopted a conciliatory policy toward their “hands.” While the most active elements among the latter were being rapidly shipped away to the Antipodes or California, the remaining toiling millions saw their earnings gradually rising, the state of employment improving, the hours of labor decreasing, their money going a longer way owing to the co-operative stores, and their leisure hours fruitfully employed in the class and lecture rooms of the numerous “Mechanics’ Institutes.” What had been formerly a despair now became a source of hope, and the details of every-day struggle now became the gospel of “small deeds.”

This it was which created the type of British workman such as we knew him throughout the remainder of the last century. The capitalist was no longer his enemy. Why should he regard him as an enemy when he found him in most cases so conciliatory and attentive to “reasonable” demands? Of course, he had to fight him sometimes or defend himself against his aggression. But there were wicked men in every class, and did not even a husband and wife sometimes quarrel? The idea of harmony between capital and labor gradually took the place of the doctrine of class war which had been propagated by the Chartists. The rest came as a natural consequence. Trade unions were necessary because some of the capitalists were wicked, but as those wicked capitalists were rather the exception, trade union policy stood in no need of militancy. On the contrary, trade union policy was to be based on the recognition of the essential good will of employers, and its objective was to be conciliation and compromise. The results of this conception were threefold. First, diplomacy became the predominant method of dealing with employers; this, in its turn, led to the moral aggrandizement of the leaders and the corresponding withdrawal of the masses, as an active factor, to the background. Secondly, it became more and more the fashion to fix the relationship between the employers and their workmen in definite treaties, discouraging all but diplomatic action, and eliminating any change of wages and hours of labor during a certain, more or less lengthy, period of time. Thirdly, the primary aim of trade unionism gradually underwent a change from that of protecting the interests of the members by supporting them in their struggles against the employing class to that of assisting them in cases of illness, death, unemployment, and so forth. Out of the first arose the corruption of the leaders, direct and indirect, since it was easy to become corrupted in the absence of all control and in the daily communion with the employers. The second was responsible for the formation of a series of obstacles to the free and immediately responsive action of the masses. The third loaded the trade union organizations with a weight of responsibilities, beyond which it became increasingly difficult for them to discharge any other. The consequence of all these developments was that in course of time, as the economic world-position of England changed and wealth no longer flowed with the same facility into the pockets of the English capitalist classes, the growing reluctance of the latter to yield more than could be extorted by the utmost pressure brought the process of improvement in the conditions of labor to a dead stop. The last twenty years and more of the last century saw practically no advance in the earnings and no reduction in the hours of labor of the working class in Great Britain. In fact, considering the ever increasing fluctuations in the state of employment, which mark the period of decline of the unchallenged supremacy of British trade and industry after the rise of Germany and the United States, it is questionable if there was not actually a retrogression in the earnings of the British working class.

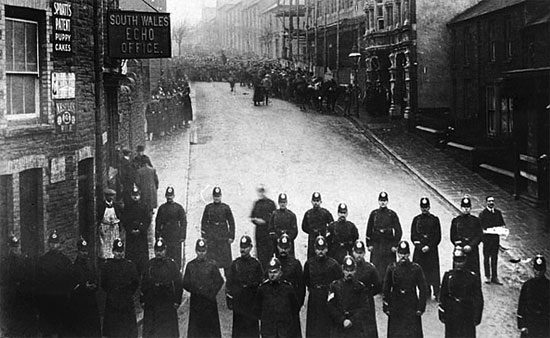

There was, however, one feature in the situation of the last quarter of the nineteenth century which mitigated its gravity, namely, the falling prices of most of the necessaries of life. There can be no doubt that though the nominal earnings of British workmen remained stationary or even decreased, their real earnings increased owing to the reduction of the cost of living. It was this circumstance which kept the British working class quiet and helped to maintain, in altered conditions, the old view and the old policy of trade unionism. Now and then, as in 1893, the miners of South Wales or as in 1897, the engineers, the working class would become conscious of the altered attitude of the employers and break out in revolt. But the situation as a whole was still tolerable, and the revolts would die away and produce no further consequences.

The rising cost of living, which may be roughly said to have commenced with the middle of the first decade of the present century, put an end to the long drawn-out idyll. The pressure of life became more and more unbearable, and then it was seen how inadequate the progress had been in the whole preceding period. The men began demanding higher wages and better conditions of labor, but instead of being met half-way, as they had expected from past experience, they found their path blocked by a colossal Frankenstein whom they themselves had reared. There were the contracts and agreements which tied them down to certain conditions and which the masters were cleverly manipulating so as to stifle all action. There were their own organizations which they had allowed to decay and to be weighted down by a vast number of obligations which had nothing to do with the fight against the employers. There were, lastly, their own leaders whom they had permitted to usurp all authority and who had grown fat and lazy in doing nothing for them and doing as much as they could for the masters. Again a feeling of despair settled upon the masses, but this time the despair spelt not inaction, but on the contrary an outburst of activity all along the line.

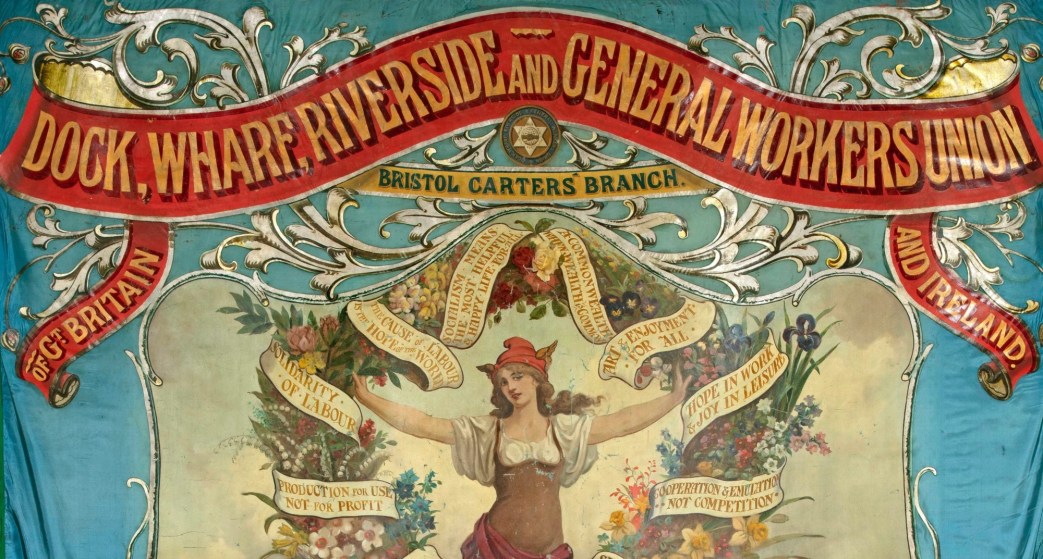

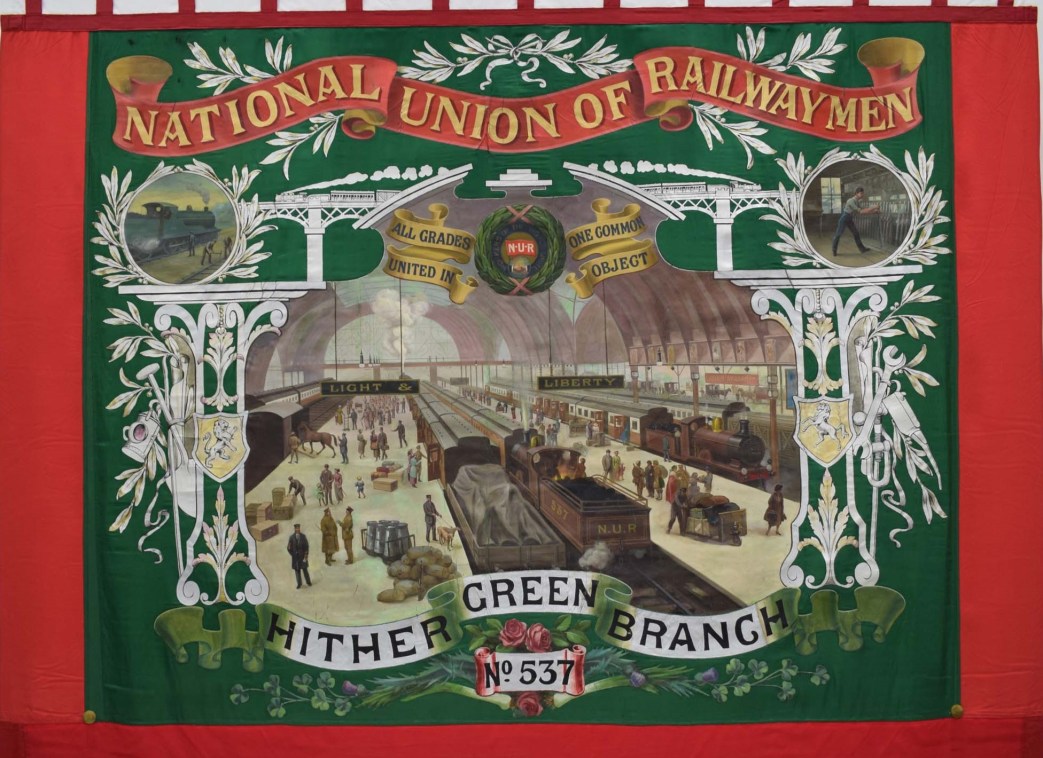

It would take us too far were we to describe this outburst in detail. It was introduced by a series of skirmishes in various industries, all bearing a distinctive character. In 1906 the South Wales miners were already busy carrying on a series of local strikes in order to force the non-unionists into the organizations. In 1907 it nearly came to a general strike on the railways. A year later we witness a seven weeks’ strike in the cotton industry, where for fifteen years previously all disputes had been amicably arranged under the famous peace treaty known as the Brook- lands Agreement. In 1909 the same industry sees the outbreak of another war over the grievance of one single man, and a very chaotic dispute takes place among the engineers of the Northeast coast against the wishes of the leaders, in consequence of which George Barnes was constrained to lay down his secretaryship. The year following sees the famous boilermakers’ strike, which must be regarded as the real beginning of the new era. What with its sectional spirit, its abhorrence of all strikes and disputes, its well-filled quasi-war chest (almost entirely invested in railway and other securities so as to avoid all temptation!), and its exemplary secretaries who held shares in the masters’ companies and accepted posts under the Government–the boilermakers’ organization had been the veritable model of a practical, level-headed British trade union. And then it suddenly broke out in revolt because the employers had not been quick enough to satisfy the grievances of a handful of its members, thus trampling under foot the most solemn agreements, repeatedly and defiantly disobeying the orders and ignoring the entreaties of the leaders, and after many months of privation and universal condemnation from all labor leaders, returning to work only after the employers had been humbled to the dust and had agreed to all their demands. In 1911 we have the remarkable tidal wave of strikes among the transport workers of all kinds in all places and the general strike of the railway men; then in 1912 the general miners’ strike and lastly, this year, again strikes upon strikes of the transport and railway workers strikes against immediate grievances, strikes for the sake of one man, strikes on account of one scab or one brutal foreman, strikes because others had struck, strikes for the sake of a principle, strikes without the consent of the leaders, strikes against the express orders of the leaders, strikes on account of “tainted” goods,-strikes without end on every imaginable occasion. It is as if the workers of Great Britain (or rather the United Kingdom, because Ireland has now been drawn into the vortex of the class war) had been bitten by some restless microbe and were impatient to make good at one blow what they had failed to achieve in the long years of their stagnation.

That they are in a great measure succeeding in this, admits of no doubt. Certainly in course of the last few years wages have risen and the general conditions of employment have improved as a direct result of the strikes and, still more perhaps, as their indirect effect. A wholesome fear has, no doubt, been planted in many an employer’s breast and a good deal of improvement has been achieved without striking a single blow. Yet this gain–quite apart from its actual amount–must be considered as of but secondary moment. Much more important is the indirect result of the awakening of the British working class to the realities of the situation. The British workman has at last realized the fatuity of his former trade union policy, and his present revolt is as much a revolt against this policy as against the employers. He no longer wants to be bound by treacherous agreements which prevent him from fighting the oppressors; he is no longer willing to surrender his rights unreservedly into the hands of his officials and other leaders, and he no longer appreciates the miraculous virtue of the diplomatic method in industrial warfare, which has reduced his militant organizations to the level of mere friendly societies. Accordingly we see how even the Brooklands Agreement is being thrown overboard by the cotton operatives who refuse to remain parties to it; how the leaders are everywhere being taken in hand and made to execute the precise instructions of the members; and how the recruiting of fresh members and the amalgamation of kindred trade unions are being pursued with a zest hitherto unknown. It is remarkable, too, as recent figures show, how less and less the workers are inclined to have outside agencies of conciliation and arbitration intervene in their disputes with the employers, preferring to have them settled by direct negotiation on their own direct responsibility. As a net result of this awakening and these practices, we have a most marvellous increase of activity among the masses and a growing sense of power such as they have not possessed since the great days of the Chartist struggle.

And already we see rising from this combination of material and moral factors a powerful sense of class consciousness finding its expression in numerous directions. The incessant conflicts on a vast scale are bringing face to face large masses of workmen and employers, which almost assume the character of classes. They also–just because they are so vast–serve to bring out the interdependence of various categories of workers not merely in the same branches of industry, but also beyond their limits. Lastly their vastness causes the hearts of all proletarians to beat in unison with those directly implicated in them and creates a bond of moral union and sympathy throughout the class. It is this new class feeling of solidarity, generated and strengthened by the struggle itself, which is responsible for the latest doctrine and practice of the sympathetic strike, of which we hear so much in these days. The sympathetic strike may be impractical; but just as little as Philip Snowden’s condemnation of the strike-practice, does the condemnation of the sympathetic strike by the trade union leaders prevent the masses from doing what is dictated to them by the feeling of fellowship with the different sections of their class. It may be foolish for the railway workers to act upon the doctrine of the sympathetic strike whenever their assistance is asked, because then the railwaymen would never come out of strikes; but when they refuse to handle goods supplied to them by blackleg labor from Dublin, where the workers are bludgeoned for maintaining their union, who but the callous or corrupt can help rejoicing at this exhibition of class solidarity and hastening to their assistance? And in the fire of this newly acquired class consciousness all the old divisions between the skilled and unskilled, between the aristocracy and democracy of labor, are being destroyed and the whole mass is being coalesced into one solid, fissureless block of a class. In the few years which have elapsed since the commencement of the present century the British working class has undergone a revolution which, taking all its aspects, material as well as moral, is nothing short of marvellous.

How does it stand in point of politics? This is a question which must rise to the mind of every Socialist, and which we must review if our subject is to be adequately dealt with.

The period of trade union decay was also the period of political decay of the British working class. The traditional view has always been that precisely because the British working class was infatuated with its trade unions it neglected the political weapon. This view, however, is only conditionally true. It is perfectly correct to say that trade unionism spread in England mainly as a reaction against the political movement of the Chartists, but we have seen how little vigor there was in its subsequent development. As a matter of fact, the same factor, the blunting of class consciousness in the British workman, which was responsible for the decay of his trade union action, was also responsible for his aversion to political action. It could not, indeed, have been otherwise. It was not trade unionism which prevented in England the rise of a political labor or Socialist movement, but it was the lack of class consciousness which acted detrimentally on both trade unionism and independent political action. We may go so far as to say that had the British working class carried on a militant policy on the economic field by means of its trade unions it would have soon found itself in the political field doing the same work by political means. The reason for this a priori assumption is obvious: a militant trade union policy presupposes as well as generates a class consciousness, a consciousness of the class antagonism between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, and class consciousness is one and indivisible and is bound to be introduced into all dealings of the proletariat with the bourgeoisie. As an a posteriori fact, whenever the British working class was driven to assume a more determined trade union policy by some provocation on the part of the capitalists it also raised the standard of political revolt. In the ‘sixties, when the trade unions, goaded by the action of the authorities in applying to them the provisions of the criminal acts, became restless, they ended by joining the International and extorting a great extension of the franchise. Ten years later when they again grew more militant because the employers made them civilly liable for their actions, they once more rushed into the political field and brought out their first labor candidatures. In our own days, as we shall presently see, the same happened with the Labor party. In a word, the lack of political activity which marks the period following the collapse of Chartism has been due to the same causes as were responsible for the decay of trade union activity: it was the absence of class consciousness which operated in the one as in the other case.

The first years of the present century also saw the rise of the Labor party. Its formation dates back to the year 1899, when the Trade Union congress adopted a resolution in favor of the establishment of a joint trade union and Socialist committee to organize and to further direct labor representation in Parliament. It was in anticipation of the next general election which was due in 1901 that the resolution was brought in and adopted, and though the suggestion itself might have been due to the obvious collapse of the Liberal party after the abandonment of Home Rule and the death of Gladstone, its aim was merely the more systematic pursuit of the policy of sending workingmen to Parliament without any specific political distinction–in reality as Liberals–which had been carried on since 1875. In other words, neither the authors of the resolution nor the majority of its supporters had anything further in their minds than the establishment of a mechanism for the more systematic creation of “Lib-Labs.” As such the committee had no historical reason for existence. The Social Democrats soon left it, and the Independent Labor party itself, opportunist as it was, would soon probably have found its position very equivocal and incompatible with its Socialist professions. As a matter of fact, the party conference of 1901 revealed unmistakable signs of premature decay, and a few years more would have seen the committee going the way of its numerous predecessors. But just in 1901 a remarkable thing happened: the House of Lords, getting bold in face of the apparent lethargy of the trade unions, let fall the famous judgment in the Taff Vale affair, and immediately the entire situation changed. The trade unions began to flock in large numbers to the Labor Representation Committee, and the Labor party movement was saved. In 1903 the first electoral contests were fought and won, and the general elections in January, 1906, saw the triumphant return to the House of Commons of a solid and enthusiastic phalanx, twenty-nine strong.

Now, one thought, the British working class was at last on its legs. It is true the movement had no program, no definite objective, and even its formal independence was ill-defined in the rules. But the way in which it fought and won its battle for the reversal of the Taff Vale judgment in the very first session of Parliament was calculated to inspire enthusiasm in the most sceptical mind, and it was generally agreed that the Labor party was likely to prove better than its theorists and official leaders. The disappointment came sooner than was expected. The very next year revealed a certain slackness in the movement; in 1908 we witness the parliamentary Labor group sedulously cooperating with the government on the Licensing Bill, with unemployment raging outside; in 1909 it ranges itself definitely on the side of the government in the matter of Lloyd George’s famous budget and the campaign against the House of Lords; in 1910 it returns from the two general elections still more chastened in mood and still more moderate in conduct; and since then it has not ventured on any single action of its own–much less on any of which the Liberal government disapproved, contenting itself with saying ditto to every government measure, including the Insurance Act, and following its direct supporters into the same lobby. Its independence has become a mere matter of form and the Liberals themselves treat it as a mere appendix to their party. Even in such situations of immediate concern as the great railway and miners’ strikes it proved worse than a broken reed: it traduced the railway men and it helped to force a compromise upon the miners.

There can be no question as to the immediate responsibility of the leaders for this debacle. Opportunists for the most part, ignorant in some cases and positively corrupt in certain individual instances, these men came to Parliament with a very hazy notion as to what they were going to do there. Some may well have thought that they had come there to fight the two bourgeois parties on behalf of the interests of the working class. But for one thing, they themselves knew little what role Parliament had to play in this fight and were inclined to exaggerate its importance as an instrument of reform, and then they soon succumbed to the superior intelligence of other men who, pro- fessing the “organic” theory of society, proved to them that from their own standpoint diplomacy, compromise and cooperation were much better than fighting. The result was the same as we saw in the trade union movement. The leaders having repudiated the militant policy and adopted the diplomatic method of warfare, the masses became superfluous and sank back into a state of inactivity and apathy, while the leaders acquired an exaggerated independence and became, by their own policy and through their constant and exclusive communion with the master class, politically corrupted. Hence, when it came to the renewal of the parliamentary mandates in the two elections of 1910, they found the masses so unresponsive that they only succeeded in retaining their seats with the help and the favor of the Liberals. This reacted on their subsequent position in Parliament and rendered them still tamer and more impotent. George Lansbury (who, by the way, deeply resented the critical remarks of the present writer in the Call at the time of the elections of 1910 on this very subject) was the first publicly to admit that the Labor party had by its tactics committed suicide, and now we have even Keir Hardie and Philip Snowden, openly lamenting the failure of their policy as having brought about the collapse of their hopes.1

To the leaders, then, with their repudiation of class antagonisms and the class war tactics, must be attributed in the first instance the debacle of the Labor party. It is obvious, however, that here, too, it is the lack of class consciousness among the masses which in the last resort is responsible for everything. Of course, it is the duty of the leaders to foster and to educate that class consciousness, and for this work no class-room or laboratory is better fitted than the Parliament. To have neglected this work and made use of Parliament for totally different purposes constitutes the unpardonable sin of the labor leaders. But from the larger, historical point of view the main cause of the evil, including the behavior and the false conceptions of the leaders themselves, will be found in the absence of class consciousness from which the workers of Great Britain have hitherto suffered. It was the masses themselves who from the very first, laboring under a very confused notion of what political independence meant, sent to Parliament as “independent” men of Labor representatives like Shackleton and Henderson and the whole crowd of trade union officials, Liberals to the core and bona-fide betrayers of the workers’ cause in the field of economic warfare. It was also the masses themselves who permitted the fight to slacken immediately after the Taff Vale fight had been won, and looked on with indifference while their representatives were assuming the grand airs of profound statesmen and hobnobbing with the political enemies of the working class. It is, as we have said, the exact parallel to that which took place in the trade unions: the same causes, the same effects, and the same phenomena.

But the same historical analysis of the fundamental causes which are responsible for the singular fortunes of the Labor party, such as we know it to-day, allows us to make a more hopeful prognostication as to the future. Because the revival of the labor movement in the economic field has not as yet been accompanied by a similar revival in the political domain, so that the Labor party still stands where it was a few years ago, the home-baked English Syndicalists have concluded that one is the effect of the other, that is, that the British working class has taken up the trade union weapon because it has become dis- appointed with the effects of political action, and that it will henceforth move along trade union lines until such time as it overthrows the capitalist order of things. This notion is pure imagination. Apart from one or two “intellectuals” who have, indeed, passed through disappointment with the Labor party into Syndicalism, the masses know nothing, either in theory or in practice, of the Syndicalist doctrines, and their present activity is due to the causes set forth above and to nothing else. By no manner of means can any Syndicalist tendencies be found in this activity. The strikes are in no way conceived by those who engage in them as the alternative to political action or as an exercise in revolutionary “gymnastics.” Nor is the weapon of the sympathetic strike and the form of organization by industry rather than by craft advocated and indulged in for any objects beyond those immediately posited by the necessities of economic warfare. If there is among the masses of the working class in Great Britain a disappointment with the Labor party, it takes the form of a relapse into the old Liberal or Tory creeds, and whatever ulterior motives may be operative, for instance, in the case of sympathetic strikes is wholly confined to the domain of simple class solidarity. But while the Syndicalists (if such exist in England outside a handful of men, many of whom, moreover, are laboring under a misapprehension of their own professed doctrines) are wrong in the interpretation of recent events, they are nevertheless correct in the statement of the fact that the extent. the intensity, and the form which trade union activity has of late assumed stand in no relation to the political interest of the masses and the concrete expression of that interest, the Liberal-Labor party. While in the field of economic warfare the masses are performing a revolutionary work of first magnitude, they not only do nothing to reform the Labor party, but they exhibit as yet no sign which could lead one to assume that in any election which might take place at the present moment they would act otherwise than vote as heretofore in the ordinary Liberal or Tory fashion.

This phenomenon is, no doubt, very baffling, but it only shows that the necessary extension of class consciousness from the economic to the political field has not yet been accomplished by the masses. Superficially considered, such an extension may appear to require merely an intellectual effort, and in fact, one often comes across the opinion that it is “intelligence” which the British masses lack. But that is a wrong view of the situation. The extension of class consciousness in the British masses from the economic to the political field is obstructed by many influences. It is more easily generated on the economic field, where the conflict of classes is more immediate. Even so it required several years before it could free itself from the material and moral shackles which had been imposed upon it by the theory and practice of old trade unionism. It cannot be otherwise with the process of clearing away the obstacles in the political domain. The duration of this process is simply a question of the growth of class consciousness in breadth and depth, which being, as I have said, one and indivisible, is bound at a given stage to overflow the ancient dams and force its way into the field of politics. Never at any given moment can it be said a priori that this stage has been reached. Experience alone can prove it. But a theoretical analysis of the forces which are now at play teaches us that that stage is inevitable and must, if the present conditions continue to obtain, come very soon-perhaps like a thief in the night.

I use intentionally the qualifying words: “If the present conditions continue to prevail.” Bourgeois society–especially in England is inexhaustible in expedients and, in England especially, it never lacks the courage to act. It is possible then–at least theoretically–that by some bold policy of concession the capitalist classes may succeed in bringing about a new reconciliation with the working class. In that case the newly acquired class consciousness may be blunted, and the whole revolutionary process, at present observable, may be stopped. The situation is too complicated to allow it to be definitely stated whether this theoretical possibility is likely or not to translate itself into practice. One feels naturally tempted to disallow such a possibility, and an attempt to set up a justification of such optimism may easily be vitiated by promptings of sympathy rather than of demonstrated fact. But on the other hand, a correct appreciation of the situation ought to lead the Socialist forces to do everything in their power to assist in the present revolutionary process by taking part in the strike movements, by endeavoring to draw into them ever larger masses, and by introducing into them as much as possible system and solidity, because only by such means can their effect upon the class consciousness be rendered more profound and rapid and its passage into the political field accelerated. That is why the proclaimed attitude of men like Snowden towards the present strikes is so wrong and so opposed to the correct policy of Socialism, and this is the reason why we regard as inadequate even that sympathy (without active cooperation) which is imposed upon its members by the British Socialist party. We regard the complete solidarity on the present occasion of the Socialist parties with the masses as their prime duty and their chief work. This is the more necessary as the time may come when the masses will revolt against their political leaders in the same way and for the same reasons as they have revolted against their trade union leaders, and the close intimacy of the Social-Democrats with them will become a matter of great and immediate importance.

Let us conclude with this note of warning. The time is heavy with momentous issues, and we must prepare ourselves to deal adequately with them.

London, Oct, 19, 1913.

1. Apropos of the well-known Leicester incident Mr. Snowden said: “If the Labor Party Executive had endorsed a second Labor candidate for Leicester, it would have jeopardised the seats of four-fifths of the present Labor members. It is no use putting forward every reason except the true one. The present labor representation in Parliament is there mainly by the goodwill of the Liberals, and it will disappear when that goodwill is turned into active resentment. It is worth serious consideration whether it would not be for the ultimate good of Socialism that we should be without representatives in Parliament until we can place them there by our own votes in the constituencies, instead of returning them by Liberal votes; for under such conditions no Labor M.P., however honest he may be, can exercise that independence which the Labor party expects from him” (“Labour Leader,” June 26, 1913). Writing on the same subject, Keir Hardie says: “We are already heavily overweighted by the Labor Alliance. We attract to our ranks the best of the active, rebellious spirits in the working class. These do not expect impossibilities, but they cannot brook being always called upon to defend and explain away the action and inaction of the parliamentary party” (“Labour Leader,” July 10, 1913). The italics are in each case ours.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1914/v2n01-jan-1914.pdf