Today marks ninety years since ‘Bloody Thursday’ during 1934’s West Coast longshore strike. Irish Hamilton reports from the scene.

‘Shoot to Kill: Civil War on the Coast’ by Irish Hamilton from New Masses. Vol. 12 No. 3. July 17, 1934.

ORDERS to militiamen were explicit,” said the paper.

“Any man who fires a shot into the air will be court-martialed,” Colonel Mittelstaedt told his men. “Shoot to kill.”

This is the stage to which the astonishing unity of the Pacific Coast strike has reduced the shipowners and employers.

On July 5th, the day of the fourteen-hour fighting that killed four men and wounded seventy-one, the Industrial Association rang up I.L.A. headquarters at 3 p.m. and asked: “Now are you ready to arbitrate?” At 3.30, as one stevedore lay dead from a policeman’s bullet, and another had his face blown off, and a marine worker both legs torn away by the Catholic mayor’s police, the Industrial Association phoned strike headquarters: “Are you ready to arbitrate now?”

For weeks the Industrial Association, led by some of the bitterest open-shop men in San Francisco, has been straining to “Open the Port.” The phrase came to have a magic meaning. President Roosevelt’s Arbitration Board set up under the new Labor Disputes Act, and composed of Archbishop Hanna, O.K. Cushing, aristocratic and conservative attorney, and Edward McGrady, Miss Perkins’ Strikebreaker Extraordinary under the N.R.A. (who sold out the railroad and the auto strikes), pleaded with the Association to delay its action. The employers did, mean while exerting pressure on Governor Merriam and Mayor Rossi for the use of police and troops. Both these officials have an election coming up and they didn’t know what effect use of troops would have on votes. Finally the Governor, counting on the easy Hitlerization of democratic Americans, decided it was all right. The Association made its gestures–a few trucks guarded by endless files of police and radio cars, flanked by mounted men, blue-uniformed throwers of tear gas, and wielders of night sticks, tootled to and from Pier 38–

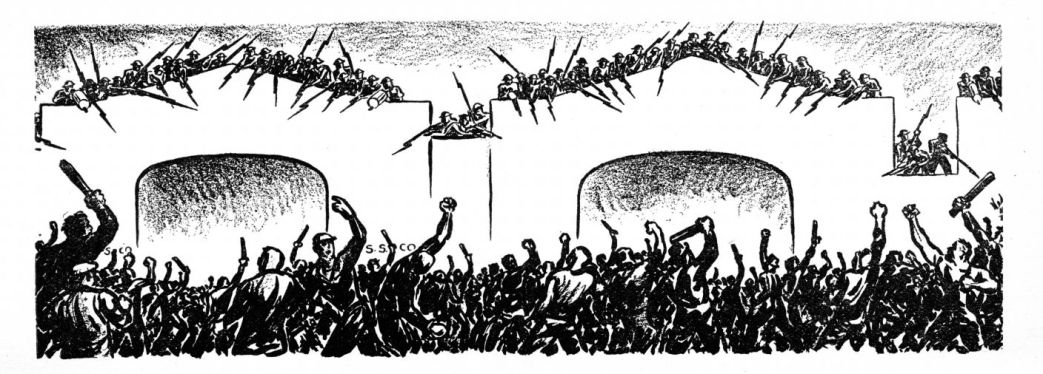

And then the pickets let loose. They overturned and burned trucks. A cargo of rice sacks was slit and the rice scattered a block. Tires were slashed, hoods ripped off. Rincon Hill, overlooking the Embarcadero was black with strikers, their sympathizers, and just “people.” Crowds had come to see the “Opening.” They saw-their City Administration’s storm-troops in action. Police shot tear gas, vomit gas and bullets wildly into the crowds; police airplanes dropped vomit gas from the air (Brisbane: Our air force must be prepared.) One cop’s tear gas gun exploded in his own face and tore his nose away. Cops threw gas bombs into the Seaboard Hotel, where many strikers lived. They shot bullets. As doctors bent over four wounded men in the I.L.A. headquarters, tear gas fumes came rolling up the stairs, and the doctors had to stop work as their eyes burned and watered; police had hurled them up after the wounded. (Four weeks ago San Francisco’s press was up in arms because ambulances said to contain wounded strikebreakers (but which actually carried healthy scabs) were stopped by strikers. The Press did not mention the hurling of tear gas into rooms filled with wounded men.)

I spoke to a cop on Rincon Hill the morning after.

“It was the crowds,” he said, “that made our work so difficult. If they would only stay away! Some of them got hurt when it wasn’t meant for them.” He was a mild sounding individual, but his pistol stuck out in front of his shabby and frayed uniform, and his black spiraling night stick bristled behind.

The police are tired. Nine weeks of twelvehour duty, with by no means tender language hurled at them twelve hours a day by the stevedores, their own pay-cut coming up next week, threats from their superiors that if they do not act mercilessly, they will lose their jobs….

All day during the clashes frantic cries came over the radio for troops, troops, troops. The State waited–Merriam trying to get Rossi to share responsibility.

When strikers halted Belt Railway, the State railroad that shunts cars along the waterfront, the Governor got his excuse. He sent troops. And now 2,000 (3,000 in reserve) young boys of 16, 17 and 18 years, the militia-boys, the National Guard, patrol the waterfront. Young boys, no down on their faces yet, trot around proudly with fixed glinting bayonets and steel helmets, watching their machine gun nests, ready to shoot to kill the stevedores born and raised in San Francisco.

(But all crews walked off the Belt Line. The railroad runs with scab crews now.)

They went, the stevedores, to their Mayor in a wild protest. One started: “Mr. Mayor, you are using force against us, born and raised in San Francisco! I am ashamed of you, Mr. Mayor!”

Mayor Rossi lost his temper and had the speaker thrown out. “We gave you your chance at arbitration,” he shouted, like Mayor La Guardia, “and you wouldn’t take it. So now you can stand the consequences, whether you like it or not!”

Another stevedore shot up: “I’m ashamed of you, Mr. Mayor! Shooting at San Franciscans! I was born and raised in San Francisco–” The Mayor had a cop throw him out, and fumed, and shouted.

Two weeks before this, after the last clashes and police show of violence, there was a meeting at Civic Auditorium. Twenty thousand people filled the vast hall. The Ladies’ Auxiliary of the I.L.A. filed in amid tremendous cheering. The Mayor spoke-and was booed till the rafters rang. He mentioned the President of the Chamber of Commerce–and the boos shook the platform. He mentioned arbitration–and was booed. After him spoke Delaney, tall, good-natured, smiling John Delaney Shoemaker, one of the beloved leaders of this strike, and the applause was deafening.

What has unleashed the civil war on the waterfront, the cruelest kind of frantic armed assault on unarmed workers? It is the unbreakable unity of the men. The Stevedores and Seamen have walked as one man in this strike. The employers still refuse to meet any of the strike committees. President Ryan of the I.L.A. made a deal on June 16 that the men would accept joint hiring halls, and next morning the newspapers rang with headlines: STRIKE OVER. By evening Ryan was repudiated up and down the Coast from Vancouver to San Diego by the rank and file. The employers stand on their dignity and say they signed the agreement in good faith, they believe Ryan did too, and therefore they expect the men to stand by it. The employers ignore completely, as Ryan carefully ignored, the fact that the men at the very beginning of their strike passed a resolution that any proposals whatsoever must be brought back to the rank and file to pass on, and that the longshoremen would not go back till the other unions’ demands had been met. The Waterfront Employers’ Association says it cannot settle the differences of other unions, since it has no quarrel with them; the employers thus deny the strikers the right to a united front, while at the same time calling on all big industry in California to join their (strike-breaking) united front.

I spoke to a reactionary City Editor from one of the big capitalist papers. “The men are unreasonable,” he said. “They don’t want to go back to work. They don’t want to settle the strike! Why should they have power to choose what men the shipping companies should employ? McGrady, Ryan, Larson, Lewis, their own leaders, told them the employers were willing to make concessions which would grant them more than they have won in fifteen years.” His voice trembled. He showed me a leaflet put out by the Communist Party to illustrate the awful things they were saying, those Communists, and his eye couldn’t find anything awful. His pointing finger trembled. He came to the line, “The lying mouthpiece of big industry–the capitalist press–has maneuvered to break the strike.” And his finger stopped pointing and he put the leaflet away.

What has “got” them all–the Chamber of Commerce, and the Governor, the mediators and arbitrators, the City Administration, the Legion, the Industrial Association–what they can’t deal with, is the solidarity of this strike. It is coming to be called the “greatest strike in American history.” The men are proud of it, consciously proud of it. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” said a striking seaman, once a Wobbly, now a member of the Marine Workers’ Industrial Union. “Only once in twenty years have I seen anything like it, and that was in Hamburg—way back.”

Relief, money, food and clothes are still flowing in. Labor unions send $1,000 a week to the longshoremen. Ralph Mallen, their publicity man, gets out clear, terse, simple statements that are printed in the papers because their sheer excellence demands it. One hundred and seventy-seven ships are tied up in San Francisco harbor. The docks are cluttered with cargo. Shops, wholesale houses, retailers are running out of goods. Scabs are getting merciless treatment from strikers. In Seattle the men discovered what power they had: Ryan had forced through an agreement to ship food to Alaska. Mayor Smith of Seattle opened one pier and forced loading by scabs under armed police protection. The men repudiated Ryan’s agreement next day.

The employers have tried every assault to crack the men’s solid determination. Harry Bridges, uncompromising leader of the Longshoremen’s Strike Committee and the Joint Marine Strike Committee, is called “communist,” “alien” and in one Chronicle editorial, “British agent”! (He is an Australian.) Hundreds of longshoremen are arrested. Every crime and outrage in San Francisco is laid to strikers. Pickets are arrested in their beds. Four girl pickets were jailed, three friends came to visit them and were arrested in the Hall of Justice on vagrancy charges, all seven held under $1,000 bail. The District Secretaries of the I.L.D. and the M.W.I.U., Joe Wilson and Sam Telford, sent telegrams of protest. Wilson was arrested on a charge of conspiracy to obstruct justice, which carries a possible ten-year sentence in San Quentin, and held on $10,000 bail or $20,000 bond. Whereupon, the National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners sent a telegram protesting the “infringement of American liberty under the Bill of Rights,” and urged Wilson’s release and that of the other prisoners; the telegram was signed by Noel Sullivan, Sara Bard Field, Charles Erskine Scott Wood, Ella Winter, Langston Hughes, Dorothy Erskine and Lincoln Steffens, National chairman. There were also a dozen other protest telegrams. Municipal Judge Steiger turned them all over to the Crime Prevention Detail and ordered their signers investigated; “and if necessary,” said the Judge, “the signers should be brought into court for questioning.” Next day the girls and their visitors were released, their cases dismissed. Three days later Wilson was released on his own recognizance. Telford was never apprehended.

The employers still use every classic device of every classic strike. They say the strike is ended when it isn’t. They report morale is breaking in the South, in the North, on the moon. They publish false figures. The State Emergency Relief Committee had to admit to a strike committee that when the papers published that relief for longshoremen was costing the city $70,000 a month these figures were false. $30,000 was nearer the truth.

False rumors are circulated daily. It was said that the strikers stopped freight cars carrying infantile paralysis serum. (A mild epidemic of this disease is sweeping California.) Next day the rumor was denied by the Superintendent of the Belt Railway; but the troops at the Monterey Presidio, for instance, said they would willingly shoot down any blankety blank strikers who stopped serum.

Another weapon is the red scare, culminating in the week-long anti-Communist drive of the American Legion. For a week they ran around to movies and churches and meetings, and the press was full of their “patriotic” inanities against Communism. The reds met this by appearing at the movie houses and booing the Legionnaires. At many gatherings these American fascists were received in stony silence. A huge anti-fascist meeting was held the same week in Veterans’ Hall, at which a Communist Party speaker excited shouts of approval and wild applause. The Legion’s “patriotic” drive ended in a gang breaking into the Western Worker office with crowbar, revolvers and clubs. But a defense corps was waiting and the Legionnaire got “the beating of his life,” and his comrades ran away fast. The day after, they broke the plate glass windows of the print shop of the Western Worker, and the day after that the insurance company cancelled its insurance.

Hearst’s Examiner reported the window breaking was “an inside Communist job intended to get the sympathy of the public.”

(The morning after the strike committee meeting with Mayor Rossi at which he defended police brutality, the windows of a florist’s shop of which he was part owner were found broken.)

But the employers’ best weapon to break the coastwise marine and longshore rank-and-file unity is being brought into play with greater and greater insistence and urgency: the district leaders of the A.F. of L. unions are bending every effort. to split up the ranks of labor. July 6th the San Francisco Labor Council under Paul Sharrenberg, a sellout artist, refused to call a general strike, though many unions had taken secret votes in favor of it. The head of the International Seamen’s Union put a resolution through demanding separation of Communist and A.F. of L. sea men. Another A.F. of L. official half promised a general strike if the I.L.A. would separate from the Communists. This resolution was passed. And when the district officials tried to oust the strike committee leaders, the rank and file wouldn’t have it. They were willing to grant the district officials a moral victory as long as they did not have to give up one real leader.

District official Lewis ran down Harry Bridges. “He’s a Communist!” he cried. The men booed Lewis.

The workers are proud of their solid fight. The rank and file want straight, uncompromising leadership which they can trust.

“We must get our men together,” said a fighting Portuguese marine worker, an indefatigable picket leader. “Here we are in five different unions, and the leaders doing their best to create enmity and confusion between us. It’s ridiculous! When we should be out picketing, we have to deal with some new trickery, point out some fresh treachery to our men, ward off another betrayal!” The teamsters had almost a pitched battle with their leader, Michael Casey, who has been against the teamsters’ strike from the beginning, is against the general strike now, and is spoken of highly by the press and the employers.

The picture of the A.F. of L. district officials is uglier than that of the student strike breakers at the beginning of the strike.

“Here’s Ryan, the men’s leader,” said my reactionary City Editor. “Why do they repudiate him?”

“I see he’s offering to call out the Atlantic longshoremen in sympathy,” I said innocently. “He won’t do that,” the editor assured me. “He has to put up some showing for the men of course. He gets a good, fat salary, doesn’t he?”

I laughed at him. “If one lets you talk long enough, you answer yourselves, don’t you?” I said.

The men have learned tremendous respect for their uncompromising leaders. To talk about arbitration at I.L.A. or Marine Workers’ headquarters is like suggesting a debutante wear a 1934 hoop-skirt. “What?” “Who?” they say.

But every day new trick resolutions are brought in by A.F. of L. leaders. Reactionaries are “phonied up, to use a good new red word, to help defeat rank and file resolutions. Because the I.S.U. “fake” leaders try to keep the seamen from picketing with the M.W. I.U., the I.S.U. seamen are opening up a desk at M.W.I.U. headquarters and issuing joint rank-and-file picket cards. These cards are also some protection to the M.W.I.U. pickets, whom the police have been consistently picking out for special persecution and arrest.

What is happening in San Francisco is happening in all Pacific ports on a smaller scale. San Francisco is the key port. Everywhere the district officials are trying the same betrayals, playing the employers’ game; everywhere there is the same line up of money, power and guns, the State and Federal governments, the press and the mediators, the Legion and the Chambers of Commerce against workers and their solidarity, against the closed shop.

If this strike is won, it will be a victory for organized labor all over the U.S.A. If it is lost, it will widen the wedge of fascism. And if it is lost because of police and gunterror, the bitterness of the men against the State and Federal governments will equal their present bitterness against the shipowners.

So far the opening of the port is only a gesture. The only thing the employers have opened is the gates of the piers. As long as no ships move out of the harbor, as long as no trucks take goods from the warehouses to their final destination, the port is no more open than it has been for nine weeks.

There is no doubt the employers are making a test of strength. How far can they go? Sentiment in San Francisco was very generally against the use of troops. It has still further strengthened rank-and-file solidarity; organized labor protests to State and Federal authorities. The day after the “riots” on Rincon Hill was a day of unwonted quiet; the workers had retired to bury their dead. A burly stevedore stands on guard outside I.L.A. headquarters where Howard Sperry was shot dead, like a pall-bearer among the wreaths and bunches of gladioli dropped on the pavement by stevedores, where the brown blood-stain still shows and POLICE MURDER is chalked up in great white letters: I.L.A. MAN SHOT HERE. POLICE MURDER. SHOT IN THE BACK. POLICE MURDER. He tells you: “The bodies will lie in state at the I.L.A. hall all day Sunday; Monday there will be a mass funeral.” You have visions of that endless line of silent men marching by the body on the docks at Odessa in the film Potemkin. The same silence has. already begun in San Francisco. Sullen and silent stevedores stand about in groups, silent and sullen on the Embarcadero, ten piers from Pier 38, every street and every cobbled lane blocked by blue and khaki-coated police; longshoremen standing, standing on an Embarcadero that has been turned into an armed camp. The employers in their desperation, in their inability to break this strike, have called in the militia with machine guns. The employers have had a bloody battle with many killed and wounded. The men’s answer to that is general strike, which would really raise the issue: 1905. But there is no certainty they can get a general strike because their leaders are not all “reds.”

Whomever you talk to in this strike, whatever you look at, wherever you go, you have an impression: the death of this system is written. The employers themselves must be aware of it. They are clinging now, as does Hitler, with inarticulate fury and the basest of behavior to stool pigeons, lies, hypocrisy, betrayals, the denial of liberty, the buying out of leaders. Whatever they touch crumbles in their hands. There is nothing left but to “shoot to kill.”

Feeling is tense. This week-end the general strike votes are to be taken. Crape waves in the breeze over the I.L.A. hall door. None are allowed up. The men’s battle lines are forming, but not on the Embarcadero. This week the unions, 120 unions embracing 45,000 men, take their general strike vote. That is their answer to the militia.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1934/v12n03-jul-17-1934-NM.pdf