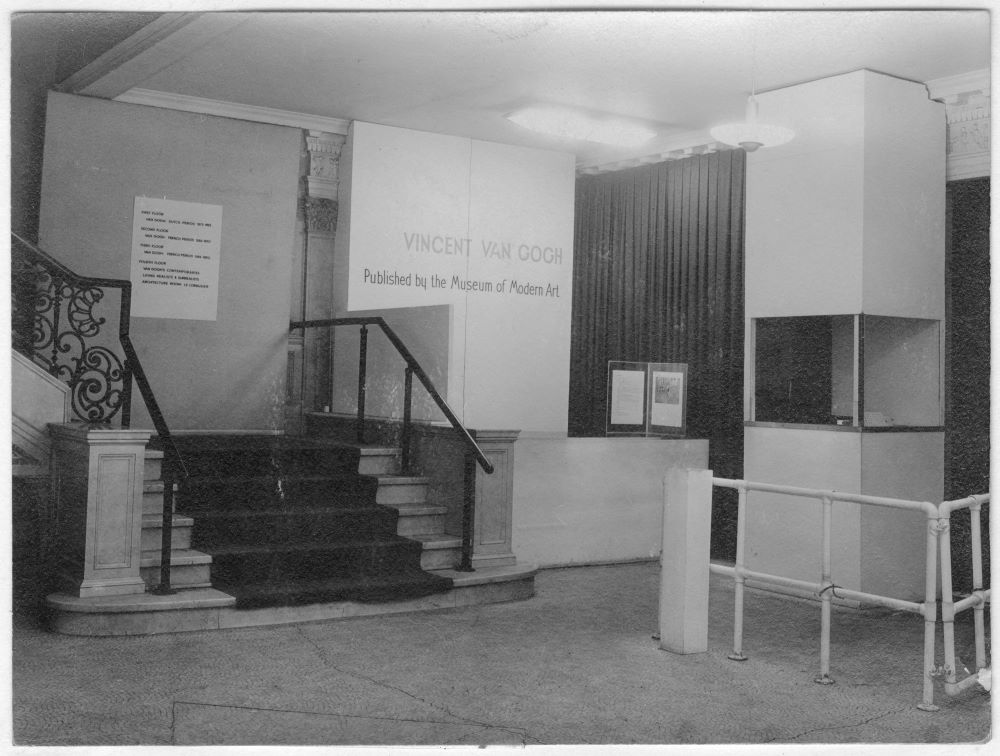

Stephen Alexander pushes through the crowds to take in the truth of the first van Gogh solo exhibition in the U.S. With 66 painting, 50 drawing, and importantly a number of his original letter to brother Theo, the Museum of Modern Art’s 1935 show was a major impetus to van Gogh popularity (and value of his art) in the United States.

‘Art In Search of Truth’ by Stephen Alexander from New Masses. Vol. 17 No. 9. November 26, 1935.

THE taxis were lined up three deep for blocks around as they crawled along waiting their turn to discharge their luxuriously dressed women and evening-clothed men into the Museum of Modern Art. This was a gala. Nothing to surpass it in the city’s art history.

Bourgeois art officialdom and particularly Society, had come to pay its respects to Vincent Van Gogh. Somewhat tardily, it is true fifty or so years too late…but as Leslie Reade has so effectively pointed out (“Post-Mortem Millions,” NEW MASSES, November 5), capitalist society is not quite as perceptive of creative values in the arts as it is in the field of munitions making. This homage to Van Gogh reminded me of an incident of which I heard a few years ago, about a great French writer who had suffered not only the physical torments of poverty and hunger during his early years, but also the racial discrimination and hatred which is the lot of most Jews under capitalism. After many years of hard struggle he achieved such critical standing that even the upper crust of bourgeois society became aware of his talents and began to seek him out for its social functions. One day he received an invitation to a banquet in his honor given by a wealthy lady who in addition to her normal snobbishness was known for her thinly-veiled anti-semitism. (Apparently she was willing to make an “exception” in this case.) The writer at first thought to reply with a curt refusal but changed his mind and decided to accept and go through with it. As the banquet progressed toward its apex and the whole disgusting circus of meaningless drivel and polite poison began to nauseate him, he created a sensation and scandal by walking out on the whole affair just as he was called upon to make the big speech of the evening.

Van Gogh would not only have walked out on this first-night crowd, but he would have (figuratively if not literally) spit upon these worthless parasites and stuffed shirts who had come to “do him honor.” (“…one would rather be in the dirtiest place where there is something to draw, than at a tea party with charming ladies.” From Van G’s letters.) Imagine if you can a more incongruous situation. Here was the work of a man who had devoted the best years of his life to a heart-rending, unceasing fight for the poor and destitute the miners, peasants, weavers, the people for whom and among whom he had lived…and now the bedecked and bespangled representatives of the exploiting class were using his paintings as an excuse for their own shallow exhibitionism and inane patter. What perversion of history and the meaning of a great artist. What bitter irony.

Capitalist society, which had starved, abused and ridiculed Van Gogh into an early suicide; which had rewarded him with the munificent sum of $129 for his art, now valued at $10,000,000. was standing in mock sorrow and reverence to do him honor, its pockets bulging with the cash of the insurance policy. Not without reason is the saying common among artists that “dealers wait for artists to die.”

But we need not permit these reactions to a first-night crowd to concern us for too long. There are more important aspects of this exhibition and of Van Gogh’s art. For one, the fact that Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and the directors of the Museum have done a splendid job in assembling and effectively mounting an exhibition, providing a rare opportunity for the serious student and lay public to obtain a comprehensive view of Van Gogh’s life work.

Van Gogh belongs to the great tradition of revolutionary art. Few people here were aware, prior to this exhibition, of the character of his early work…the powerful, somber-colored drawings and paintings of the peasants and workers among whom he lived. It is only when his work is taken in its entirety that it can be understood in its proper significance. Both his early work and his later, impressionist paintings are complementary aspects of a single fundamental attitude. Van Gogh was in search of truth. (“At bottom nature and the true artists agree.” From Van G’s letters.) Violently, uncompromisingly in search of truth. He loved humanity and nature warmly and with passionate intensity. His simplicity was tantamount to a fanatic honesty. He set down on canvas and in drawings his straightforward observations and knowledge of life about him in essentially the same manner…whether it was a weaver at work, a peasant woman’s head, or a vase of flowers. If in the first instances he saw with low-keyed, almost monochromatic color and heavy earth-like forms and in later years with the blazing swirling color of the impressionists, these differences are superficial rather than fundamental. The vocabulary had changed but the meaning was still the same. Van Gogh was in search of truth.

If he took the orthodox church at its word, attempted to put into practice its preachings among the Borinage miners and was rebuffed by the official representatives of God for his crude, sincere and direct methods, he would turn to art, where surely he could tell the truth.

Here he could speak freely, he thought. But he soon learned to his bitter experience that here too was an entrenched hierarchy reactionary and antagonistic to the truth, to his truth. Painter, critic and dealer alike had no use for him. What need had a smug, effete mercantile bourgeoisie for these deeply sympathetic, tragic statements of the lives of the working class on the walls of their luxurious homes? They would have none of this awkward uncouth lout…who did not know how to draw, nor the meaning of art. Van Gogh’s dynamic, radiant statements about nature were no better received than were his earlier statements about humanity. Alike they were treated with antagonism, scorn, ridicule. Even a throbbingly beautiful canvas, now valued at $50,000, of a bunch of flowers, was worthless to the art buyers of his day. Nature too, had to conform to the desires and taste of the dominant class.

The bourgeois press has, with wonder, awe and in some cases poignancy, described the great discrepancy between the present-day value of Van Gogh’s art and the reward that society paid him during his life. The story of Van Gogh has been made into a romantic bit of “human-interest stuff” for the Sunday supplement. But the real meaning of Van Gogh they have hidden deep between the lines. For when living artists attempt to follow in Van Gogh’s footsteps…to tell the truth…they, too, quickly find themselves outcasts and enemies of the powers that be. Capitalist society honors Van Gogh in the breach. The radical artist today knows that to tell the truth is to be labeled a criminal, a dangerous person, a propagandist, a Red.

If Van Gogh fought individually and blindly for a decent and a better world, and went down to defeat during his lifetime, his work has nevertheless served and will continue to serve as an inspiration to those artists who are today fighting in more organized, clear and conscious manner for the same ends. Van Gogh belongs to us.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1935/v17n09-nov-26-1935-NM.pdf