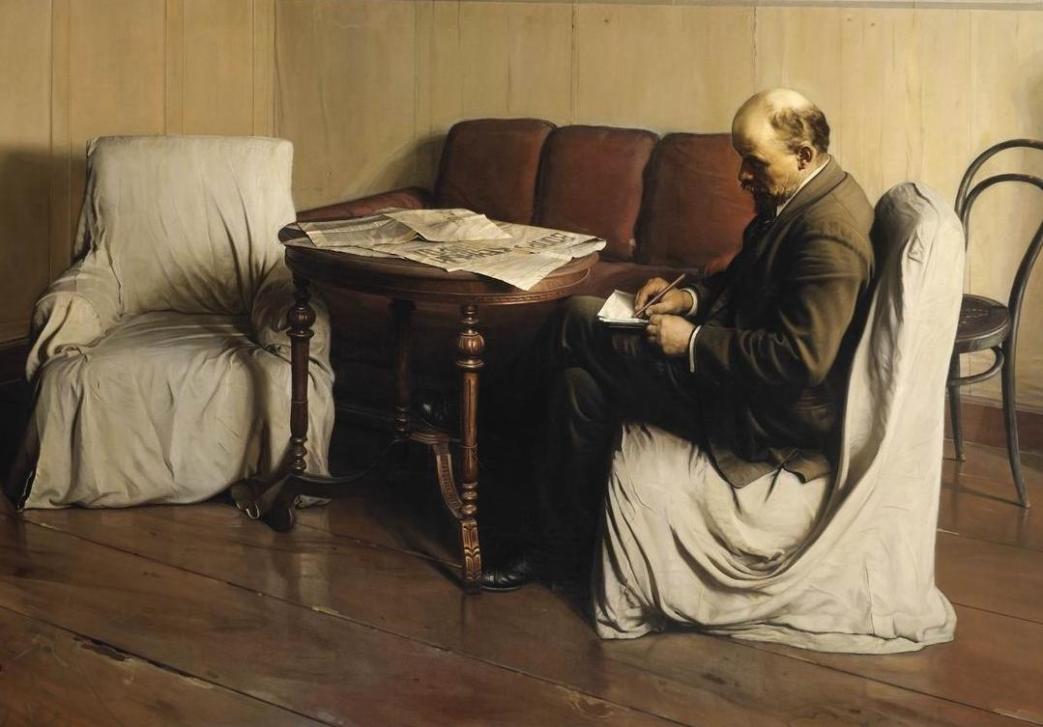

Written by Lenin in 1908 on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of Marx’s death for a collection, ‘ In Memory of Karl Marx,’ which was immediately suppressed by Tsarist authorities. Lenin wrote a great number of articles attacking the revisionism of Marx that became increasingly predominate in the movement after Engels’ 1895 death, however this essay serves well as an introduction and summary of Lenin’s arguments against the Revisionists up to that time.

‘Marxism and Revisionism’ (1908) by V.I. Lenin from Selected Works, Vol. 11. International Publishers, New York. 1937.

THERE is a saying that if geometrical axioms affected human interests attempts would certainly be made to refute them. Theories of the natural sciences which conflict with the old prejudices of theology provoked, and still provoke, the most rabid opposition. No wonder, therefore, that the Marxian doctrine, which directly serves to enlighten and organise the advanced class in modern society, which indicates the tasks of this class and which proves the inevitable (by virtue of economic development) replacement of the present system by a new order—no wonder that this doctrine had to fight at every step in its course.

There is no need to speak of bourgeois science and: philosophy, which are officially taught by official professors in order to befuddle the rising generation of the possessing classes and to “‘coach” it against the internal and foreign enemy. This science will not even hear of Marxism, declaring that it has been refuted and annihilated. The young scientists who are building their careers by refuting Socialism, and the decrepit elders who preserve the traditions of all the various outworn “systems,” attack Marx with equal zeal. The progress of Marxism and the fact that its ideas are spreading and taking firm hold among the working class inevitably tend to increase the frequency and intensity of these bourgeois attacks on Marxism, which only becomes stronger, more hardened, and more tenacious every time it is “annihilated” by official science.

But Marxism by no means consolidated its position immediately even among doctrines which are connected with the struggle of the working class and which are current mainly among the proletariat, In the first half-century of its existence (from the “forties on) Marxism was engaged in combating theories fundamentally hostile to it. In the first half of the forties Marx and Engels demolished the radical Young Hegelians, who professed philosophical idealism. At the end of the “forties the struggle invaded the domain of economic doctrine, in opposition to Proudhonism. The ‘fifties saw the completion of this struggle: the criticism of the parties and doctrines which manifested themselves in the stormy year of 1848, In the “sixties the struggle was transferred from the domain of general theory to a domain closer to the direct labour movement: the ejection of Bakunism from the International. In the early ’seventies the stage in Germany was occupied for a short while by the Proudhonist Muhlberger, and in the latter ’seventies by the positivist Duhring. But the influence of both on the proletariat was already absolutely insignificant. Marxism was already gaining an unquestionable victory over all other ideologies in the labour movement.

By the ’nineties this victory was in the main completed. Even in the Latin countries, where the traditions of Proudhonism held their ground longest of all, the labour parties actually based their programmes and tactics on a Marxist foundation. The revived international organisation of the labour movement—in the shape of periodical international congresses—from the outset, and almost without a struggle, adopted the Marxist standpoint in all essentials. But after Marxism had ousted all the more or less consistent doctrines hostile to it, the tendencies expressed in those doctrines began to seek other channels. The forms and motives of the struggle changed, but the struggle continued. And the second half-century in the existence of Marxism began (in the ’nineties) with the struggle of a trend hostile to Marxism within Marxism.

Bernstein, a one-time orthodox Marxist, gave his name to this current by making the most noise and advancing the most consistent expression of the amendments to Marx, the revision of Marx, revisionism. Even in Russia, where, owing to the economic backwardness of the country and the preponderance of a peasant population oppressed by the relics of serfdom, non-Marxian Socialism has naturally held its ground longest of all, it is plainly passing into revisionism before our very eyes. Both in the agrarian question (the programme of the municipalisation of all land) and in general questions of programme and tactics, our social-Narodniks are more and more substituting “amendments” to Marx for the moribund and obsolescent remnants of the old system, which in its own way was consistent and fundamentally hostile to Marxism.

Pre-Marxian Socialism has been smashed. It is now continuing the struggle not on its own independent soil but on the general soil of Marxism—as revisionism. Let us, then, examine the ideological content of revisionism.

In the domain of philosophy, revisionism clung to the skirts of bourgeois professorial “science.” The professors went “back to Kant”—and revisionism followed in the wake of the Neo-Kantians. The professors repeated the threadbare banalities of the priests against philosophical materialism—and the revisionists, smiling condescendingly, mumbled (word for word after the latest Handbuch) that materialism had been “refuted” long ago. The professors treated Hegel as a “dead dog,” and while they themselves preached idealism, only an idealism a thousand times more petty and banal than Hegel’s, they contemptuously shrugged their shoulders at dialectics—and the revisionists floundered after them into the swamp of philosophical vulgarisation of science. replacing “artful” (and revolutionary) dialectics by “simple” (and tranquil) “evolution.” The professors earned their official salaries by adjusting both their idealist and “critical” systems to the dominant medieval “philosophy” (i.e., to theology)—and the revisionists drew close to them and endeavoured to make religion a “private affair,” not in relation to the modern state, but in relation to the party of the advanced class.

What the real class significance of such “amendments” to Marx was need not be said—it is clear enough. We shall simply note that the only Marxist in the international Social-Democratic movement who criticised from the standpoint of consistent dialectical materialism the incredible banalities uttered by the revisionists was Plekhanov. This must be stressed all the more emphatically since thoroughly mistaken attempts are being made in our day to smuggle in the old and reactionary philosophical rubbish under the guise of criticising Plekhanov’s tactical opportunism.1

Passing to political economy, it must be noted first of all that the “amendments” of the revisionists in this domain were much more comprehensive and circumstantial; attempts were made to influence the public by adducing “new data of economic development.” It was said that concentration and the ousting of small-scale production by large-scale production do not occur in agriculture at all, while concentration proceeds extremely slowly in commerce and industry. It was said that crises had now become rarer and of less force, and that the cartels and trusts would probably enable capital to do away with crises altogether. It was said that the “theory of the collapse” to which capitalism is heading, was unsound, owing to the tendency of class contradictions to become less acute and milder. It was said, finally, that it would not be amiss to correct Marx’s theory of value in accordance with Böhm-Bawerk,.

The fight against the revisionists on these questions resulted in as fruitful a revival of the theoretical thought of international Socialism as followed from Engels’ controversy with Duhring twenty years earlier. The arguments of the revisionists were analysed with the help of facts and figures. It was proved that the revisionists were Systematically presenting modern small-scale production in a favourable light. The technical and commercial superiority of large-scale production over small-scale production both in industry and in agriculture are proved by irrefutable facts. But commodity production is far less developed in agriculture, and modern statisticians and economists are usually not very skillful in picking out the special branches (sometimes even operations) in agriculture which indicate that agriculture is being progressively drawn into the exchange of world economy. Small-scale production maintains itself on the ruins of natural economy by a steady deterioration in nourishment, by chronic starvation, by the lengthening of the working day, by the deterioration in the quality of cattle and in the care given to cattle, in a word, by the very methods whereby handicraft production maintained itself against capitalist manufacture. Every advance in science and technology inevitably and relentlessly undermines the foundations of small-scale production in capitalist society, and it is the task of Socialist economics to investigate this process in ail its—often complicated and intricate— forms and to demonstrate to the small producer the impossibility of holding his own under capitalism, the hopelessness of peasant farming under capitalism, and the necessity of the peasant adopting the standpoint of the proletarian, On this question the revisionists sinned from the scientific standpoint by superficially generalising from facts selected one-sidedly and without reference to the system of capitalism as a whole; they sinned from the political standpoint by the fact that they inevitably, whether they wanted to or not, invited or urged the peasant to adopt the standpoint of the master (i.e., the standpoint of the bourgeoisie), instead of urging him to adopt the standpoint of the revolutionary proletarian.

The position of revisionism was even worse as far as the theory of crises and the theory of collapse were concerned. Only for the shortest space of time could people, and then only the most shortsighted, think of remodeling the foundations of the Marxian doctrine under the influence of a few years of industrial boom and prosperity. Facts very soon made it clear to the revisionists that crises were not a thing of the past: prosperity was followed by a crisis. The forms, the sequence, the picture of the particular crises changed, but crises remained an inevitable component of the capitalist system. While uniting production, the cartels and trusts at the same time, and in a way that was obvious to all, aggravated the anarchy of production, the insecurity of existence of the proletariat and the oppression of capital, thus intensifying class contradictions to an unprecedented degree. That capitalism is moving towards collapse—in the sense both of individual political and economic crises and of the complete wreck of the entire capitalist system—has been made very clear, and on a very broad scale, precisely by the latest giant trusts. The recent financial crisis in America and the frightful increase of unemployment all over Europe, to say nothing of the impending industrial crisis to which many symptoms are pointing—all this is resulting in the fact that the recent “theories” of the revisionists are being forgotten by everybody, even, it seems, by many of the revisionists themselves. But the lessons which this instability of the intellectuals has given the working class must not be forgotten.

As to the theory of value, it should only be said that apart from hints and sighs, exceedingly vague, for Böhm-Bawerk,, the revisionists have here contributed absolutely nothing, and have therefore left no traces whatever on the development of scientific thought.

In the domain of politics, revisionism tried to revise the very foundation of Marxism, namely, the doctrine of the class struggle. Political freedom, democracy and universal suffrage remove the ground for the class struggle—we were told—and render untrue the old proposition of the Communist Manifesto that the workers have no country, For, they said, since the “will of the majority” prevails under democracy, one must neither regard the state as an organ of class rule, nor reject alliances with the progressive, social-reformist bourgeoisie against the reactionaries.

It cannot be disputed that these objections of the revisionists constituted a fairly harmonious system of views, namely, the old and well-known liberal bourgeois views. The liberals have always said that bourgeois parliamentarism destroys classes and class divisions, since the right to vote and the right to participate in state affairs are shared by all citizens without distinction. The whole history of Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century, and the whole history of the Russian revolution at the beginning of the twentieth, clearly show how absurd such views are. Economic distinctions are aggravated and accentuated rather than mitigated under the freedom of “democratic” capitalism. Parliamentarism does not remove, but rather lays bare the innate character even of the most democratic bourgeois republics as organs of class oppression. By helping to enlighten and to organise immeasurably wider masses of the population than those which previously took an active part in political events, parliamentarism does not make for the elimination of crises and political revolutions, but for the maximum accentuation of civil war during such revolutions. The events in Paris in the spring of 1871 and the events in Russia in the winter of 1905 showed as clear as clear could be how inevitably this accentuation comes about. The French bourgeoisie without a moment’s hesitation made a deal with the common national enemy, the foreign army which had ruined its fatherland, in order to crush the proletarian movement. Whoever does not understand the inevitable inner dialectics of parliamentarism and bourgeois democracy—which tends to an even more acute decision of a dispute by mass violence than formerly—will never be able through parliamentarism to conduct propaganda and agitation that are consistent in principle and really prepare the working-class masses to take a victorious part in such “disputes.” The experience of alliances, agreements and blocs with the social-reformist liberals in the West and with the liberal reformists (Constitutional-Democrats) in the Russian revolution convincingly showed that these agreements only blunt the consciousness of the masses, that they weaken rather than enhance the actual significance of their struggle by linking the fighters with the elements who are least capable of fighting and who are most vacillating and treacherous. French Millerandism—the biggest experiment in applying revisionist political tactics on a wide, a really national scale—has provided a practical judgment of revisionism which will never be forgotten by the proletariat all over the world.

A natural complement to the economic and political tendencies of revisionism was its attitude to the final aim of the Socialist movement, “The final aim is nothing, the movement is everything”— this catch-phrase of Bernstein’s expresses the substance of revisionism better than many long arguments, The policy of revisionism consists in determining its conduct from case to case, in adapting itself to the events of the day and to the chops and changes of petty politics; it consists in forgetting the basic interests of the proletariat, the main features of the capitalist system as a whole and of capitalist evolution as a whole, and in sacrificing these basic interests for the real or assumed advantages of the moment. And it patently follows from the very nature of this policy that it may assume an infinite variety of forms, and that every more or less “new” question, every more or less unexpected and unforeseen turn of events, even though it may change the basic line of development only to an insignificant degree and only for the shortest period of time, will always inevitably give rise to one or another variety of revisionism.

The inevitability of revisionism is determined by its class roots in modern society. Revisionism is an international phenomenon. No more or less informed and thinking Socialist can have the slightest doubt that the relation between the orthodox and the Bernsteinites in Germany, the Guesdites and the Jaurésites (and now particularly the Broussites) in France, the Social-Democratic Federation and the Independent Labour Party in Great Britain, de Brouckére and Vandervelde in Belgium, the integralists and the reformists in Italy, and the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks in Russia is everywhere essentially similar, notwithstanding the gigantic variety of national and historically-derived conditions in the present state of all these countries. In reality, the “division” within the present international Socialist movement is now proceeding along one line in all the various countries of the world, which testifies to a tremendous advance compared with thirty or forty years ago, when it was not like tendencies within a united international Socialist movement that were combating one another within the various countries, And the “revisionism from the Left” which has begun to take shape in the Latin countries, such as “revolutionary syndicalism,” is also adapting itself to Marxism while “amending” it; Labriola in Italy and Lagardelle in France frequently appeal from Marx wrongly understood to Marx rightly understood.

We cannot stop here to analyse the ideological substance of this revisionism; it has not yet by far developed to the extent that opportunist revisionism has, it has not yet become international, and it has not yet stood the test of one big practical battle with a Socialist Party even in one country. We shall therefore confine ourselves to the “revisionism from the Right” described above,

Wherein lies its inevitability in capitalist society? Why is it more profound than the differences of national peculiarities and degrees of capitalist development? Because in every capitalist country, side by side with the proletariat, there are broad strata of the petty bourgeoisie, small masters. Capitalism arose and is constantly arising out of small production. A number of “middle strata” are inevitably created anew by capitalism (appendages to the factory, home work, and small workshops scattered all over the country in view of the requirements of big industries, such as the bicycle and automobile industries, etc.). These new small producers are just as inevitably cast back into the ranks of the proletariat. It is quite natural that the petty-bourgeois world conception should again and again crop up in the ranks of the broad labour parties. It is quite natural that this should be so, and it always will be so right up to the commencement of the proletarian revolution, for it would be a grave mistake to think that the “complete” proletarianisation of the majority of the population is essential before such a revolution can be achieved. What we now frequently experience only in the domain of ideology—disputes over theoretical amendments to Marx —what now crops up in practice only over individual partial issues of the labour movement as tactical differences with the revisionists and splits on these grounds, will all unfailingly have to be experienced by the working class on an incomparably larger scale when the proletarian revolution accentuates all issues and concentrates all differences on points of the most immediate importance in determining the conduct of the masses, and makes it necessary in the heat of the fight to distinguish enemies from friends and to cast out had allies, so as to be able to deal decisive blows at the enemy.

The ideological struggle waged by revolutionary Marxism against revisionism at the end of the nineteenth century is but the prelude to the great revolutionary battles of the proletariat, which is marching forward to the complete victory of its cause despite all the waverings and weaknesses of the petty bourgeoisie.

April 1908.

1. See Studies in the Philosophy of Marxism by Bogdanov, Bazarov and others. This is not the place to discuss the book, and I must at present confine myself to stating that in the very near future I shall prove in a series of articles, or in a separate pamphlet, that everything I have said in the text about neo-Kantian revisionists essentially applies also to these “new” neo-Humist and neo-Berkeleyan revisionists.—Lenin

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/selected-works-vol.-11/Selected%20Works%20-%20Vol.%2011.pdf