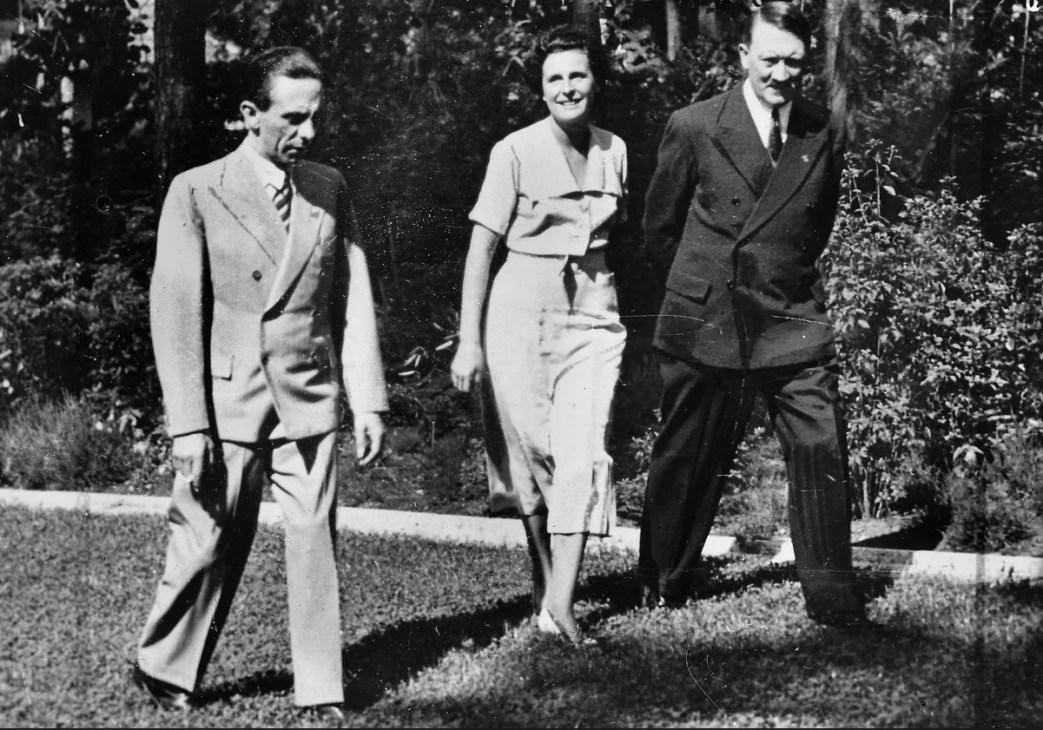

Stimulating insights on the uses of film and its stars, and the ease in which bourgeois film can become fascist film in two parts: The Films of the Bourgeoisie and The Road to Hitler Is Paved With Film and Stars. Béla Balázs was a poet, screenplay writer, and hugely influential formalist film and arts critic. A Hungarian Jew born in 1884, he was part of Budapest’s Sonntagskreis (Sunday Circle) of intellectuals that included Karl Mannheim, Arnold Hauser and György Lukács. After the fall of the Hungarian Soviets in 1919, Balázs moved to Vienna, then Berlin where he immersed himself in the Weimar-era radical arts scene. He worked with Leni Riefenstahl on her first film in 1932, shortly to have his name removed from the credits because of his Jewish heritage. After Hitler took power, he moved to Moscow where these articles were written, and which in part come from a lecture to the Moscow Film Workers Union. Returning to Hungary after the Second World War he died in 1949 just after finishing his Theory of the Film, which was published posthumously.

‘Film Into Fascism’ by Béla Balázs from New Theatre. Vol. 1 Nos. 8 & 9. September & October, 1934.

I. The Films of the Bourgeoisie

THE events of the past two years in Germany have shown us very clearly and brutally how important it is to analyze and clarify bourgeois film propaganda. Fascism did not drop from the sky overnight. Seventeen million votes–a great mass movement must have been prepared over a long period, and by means of the most diverse methods of influence. We, in Germany, were not sufficiently prepared theoretically to evaluate and combat the subtle, uncommonly cunning forms of influence used in pre-Nazi films. We did not see just what psycho-technical methods they enlisted to bring the petty bourgeois mass into the fascist current. It is our problem now to liquidate this theoretical shallowness. In countries other than Germany the danger is still in the stage where it can be opposed more successfully than is now possible in Germany.

A few examples will show how the bourgeois film has been used not only to divert but to convert–how it was used in Germany and how it is being used elsewhere now to create a definite fascist ideology. I want to indicate the psychological influences that were employed in Germany to snare the sympathy of the blindly confident, blissfully ignorant petty bourgeois mass which was not clearly petty bourgeois mass which was not clearly conscious of its own interests.

Why does every bourgeois film employ love as its theme? Not only because it is a pleasant thing, which diverts, but also, because love is portrayed as a power of nature that has nothing to do with social concerns. We know that this is not true. But the bourgeois film presents it in this manner. In these films love is victorious over all class contradictions. They influence the petty bourgeois by suggestion; there are powerful contradictions in the social situation, but in the movies, love is all.

The second main theme is crime, the detective story. The film shows how a safe is cracked, but not how it is filled. The petty bourgeois is diverted by one danger (that of the robber) from the other. But how does conversion enter here? Who is the detective, the hero? The protector of private property. Because this figure is idealized, the worth and the meaning of private property is idealized. Have you seen films in which the burglars are poor people, who steal for a piece of bread? The social problem is not mentioned once in this form. We are in such high society that even the burglar appears in a full dress suit. However, in Germany, poor people were shown in films. These films about “poor people” are no less dangerous than the others. Even in the best of them only those who have fallen by the wayside, the lumpen-proletariat are shown: drunkards, thieves, beggars, people who are so humbled and poor, that they are portrayed as victims.

What is the psychology and influence of this type of film? When the petty bourgeois sees misery where help is no longer possible, he is partly soothed. Because, when you cannot help any more, you need not help any more. Therefore these broken creatures are not dangerous people.

Have you ever seen a film showing the awakened proletariat? Never. Even in our films, those made by our own side, this error was committed, e.g., Mother Krausen. This film which was praised by us as proletarian, is really the opposite, because it does not show the fighting proletariat at all, but the fallen, lumpen-proletariat. There is another form, the smug, but very efficient fascist film. These films are fashioned after historical anecdotes in monarchist style. The princes and kings are magnificent people. No money is spared in production. Imposing decorations produce a splendor that always intoxicates the petty bourgeois. He thinks, “Ah, it was beautiful then.” He forgets what is close to home. Thus it goes step by step until the fascist taint of the production becomes most distinct. I speak of German experiences, but we know that in other countries similar forms exist.

For years it was the custom in Germany to make charming light opera films about small principalities. It is worth analyzing the fascist effect of these films, for they were not so primitive that they merely praised the feudal court. Our enemies do not work so obviously. These courts were even caricatured, made ridiculous. They certainly were not dangerous; they were such little illusions, somehow very congenial. One laughs; it would not be unpleasant to live there. But in every one of these films there is one person who is not ridiculous–the young prince or the young princess. He is modern, thoroughly; he makes the great court appear very ridiculous, and the petty bourgeois feels sympathetic with him. He appears in the films as one who no longer represents the old feudal ideology, but as a modern and democratic man. The petty bourgeois approves of such a man. This tendency is pursued in a seemingly accidental way, but the flood of these films demonstrate that this is no accident. Anyone can name ten such films. For years the German film prepared for fascism. There was a series of films in Germany on “Old Fritz” and Queen Louise. There was one year in which seven pictures about “Old Fritz” and five about Queen Louise were made. What is there in them that is not simply diversion, not simply historical nonsense? The “Old Fritz” is not shown as a ruler in his castle, but as a friend of the soldiers, who also wears torn boots, who eats the same meals as the soldier. The petty bourgeois is deeply impressed by seeing a king sip his soup! “Then I too can die for him. When he goes about in such worn boots, how can I complain that I have none. How can I complain of the danger of war when the king himself shares this danger with me?” The powerful comradeship ideology which is intended to bridge over class distinctions, is the fascist ideology.

A year later there was another flood–the military farce. It is uncanny to see, when you look back now, how systematically this line was pursued year after year. It was as if they had a five-year plan, to accomplish their fascist propaganda. The military farce was tremendously successful. War was still unpopular at that particular time, even with the petty bourgeoisie. For many years neither military films nor war films could be shown. But they showed pre-war barrack life in the form of parodies and comedies. Life there was really so comical and comfortable. When one sees these films one cannot understand at all the high percentage of soldier suicides. The uniform again becomes likable. When I laugh, I hate no more. It really seems as if it were not at all bad.

During the next season, the serious war films, “pacifist” films, suddenly appeared. These films must be analyzed a little differently. There are some among them that should really have revolutionary effect simply because war is shown with all its horrors. But the psycho-technique of the war films, as of the literature that came at the same time, is: War is terrible, but it is a natural catastrophe; nobody can do anything about it. No word, no question about who causes it, who gains by it. In All Quiet on the Western Front there is a scene in which the soldiers discuss this problem. The answer is to the effect that war is like the rain. In all these films the characteristic attributes inherent in war were idealized: comradeship, manliness and loyalty. This is now clearly defined fascist ideology portraying war as a moral institution. The film takes on a dangerous form the instant that comradeship and loyalty transcend class distinctions. In the trenches all are alike, it is said, and therefore, when in the trench a shell can kill a private and an officer with one shot–with that, class distinction seems to be removed. To the happy-go-lucky proletarian and petty bourgeois this is really a sensation of satisfaction. He has the feeling that here we are equal, here there are no class differences.

There are films that make war disagreeable because they show war too clearly, but even this type of film has the ideological point that shows war as a natural catastrophe. There is a French documentary montage film called For the Peace of Humanity. This is not a revolutionary film in our sense, but it is truly pacifist. It was issued by people who have been wounded so horribly that they can no more mingle with others. The film is dedicated to the eight cameramen who were killed in photographing it. It is an original cinema study of a group of French soldiers who capture a German trench. One of the subtitles reads: “As soon as the German soldiers were released from the firing, they helped us to gather the wounded.” One scene shows the destroyed vineyards of Champagne. The audience sighed so at this point that I was sure. there would be an anti-German demonstration. But the title to the scene is not “The Germans did this,” but “This is war.” We wanted to exhibit this picture in the Volkfilmverband in Germany, but it was impossible. All Quiet on the Western Front was publicly prohibited, though actually everyone could see it, since it was allowed to be shown at closed organizations. This was only a matter of form, since everyone could enter. The Peace of Humanity was suppressed.

It becomes clear that theme itself can be a transition toward fascist ideas. Nature films, for example. Man in his battle with Nature has nothing to do with class war, they point out. Take North Pole expeditions. Why they are made is not discussed. Naked man is pitted against naked Nature, and so they seek to camouflage the class war.

The film is the first art that originated in the bourgeois era. None of the other arts (which still retain some feudal forms) exhibit the bourgeois ideology as clearly as the movie. It is characteristic that, although the movie apparatus was invented in France and the first movies were made there, film making did not advance a step in that country for twelve years. Films remained pantomime. The artistic form of the film stems from America. It was the Americans who discovered continuity, montage, etc.

The other arts as a whole, which have an older tradition are, so to speak, isolated from their spectators. A picture is framed and I look. at it. In the theatre I sit before the stage as before an altar. There is a distance between me and the theatre; I cannot enter. These arts have grown out of the Church arts, and the early form, the holy unapproachability, was retained. The film has created an entirely new art form, since it annihilates distance. The fashion of five thousand years of art is thereby destroyed. The distance of the spectator, the enclosed art form, is destroyed. That was an American discovery, a bit of bourgeois demagogy; I might say a bourgeois revolution.

The Russian film needed and developed new forms to express a new life. It is not by accident that the bourgeoisie considers montage a peculiarly Russian art. Montage in revolutionary Russian films is different from montage in bourgeois films. In the latter, it is employed only to make the plot clear and lively. In the former, montage means connection between facts which have a social content. For example, in The End of St. Petersburg, the Bourse is shown. The next scene is a battlefield. This is montage which does not relate to plot, but to a political idea which indicates a definite relation.

In conclusion it is necessary to analyze the bourgeois film thematically more thoroughly than we have done so far. We must not dismiss this issue with the word “diversion,” but in every case we must unmask and uncover the psychological method. Further, we must consider the formal problems of the films for their ideological effect, so that we can recognize the difference between the bourgeois and revolutionary influence. We must not, on the other hand, descend to revolutionary formalism, which sometimes hap- pens in bad Russian films. There was a time when the bourgeois was always the fat man from whose jaws grease dripped. Capitalism, of course, is not to be fought because one individual is bad, but because the system is bad. These are the problems which we must work out.

Translated by H. Berman and F. Laurfera from a lecture delivered to Moscow Film Workers.

II. The Road to Hitler Is Paved With Film Stars

IN the past, the ruling classes utilized religion for the persuasion of the masses. Developed monopolistic capitalism more often uses art and the press. For imperialist capitalism, the film is the most adaptable means, because a wide mass influence is assured and because as one of capital’s big industries it is thoroughly controlled economically. In addition, the film, as in the case of religion, functions not only to lull criticism generally, to preach pious patience in bearing every misery, but even more certainly in the direction of fascism. Whether this happens consciously or unconsciously is of slight importance.

The ideological preparation for fascism took place in Germany naturally, in literature as well as in all the other arts. But perhaps not so definitely, so penetratingly as in the standardized production methods of films, where an increasingly monopolized industry admitted less and less the voice of individual or other opposition. Every season a deluge of feature subjects fashioned from the same mould was thrown on the market.

The Ideology of the Stars

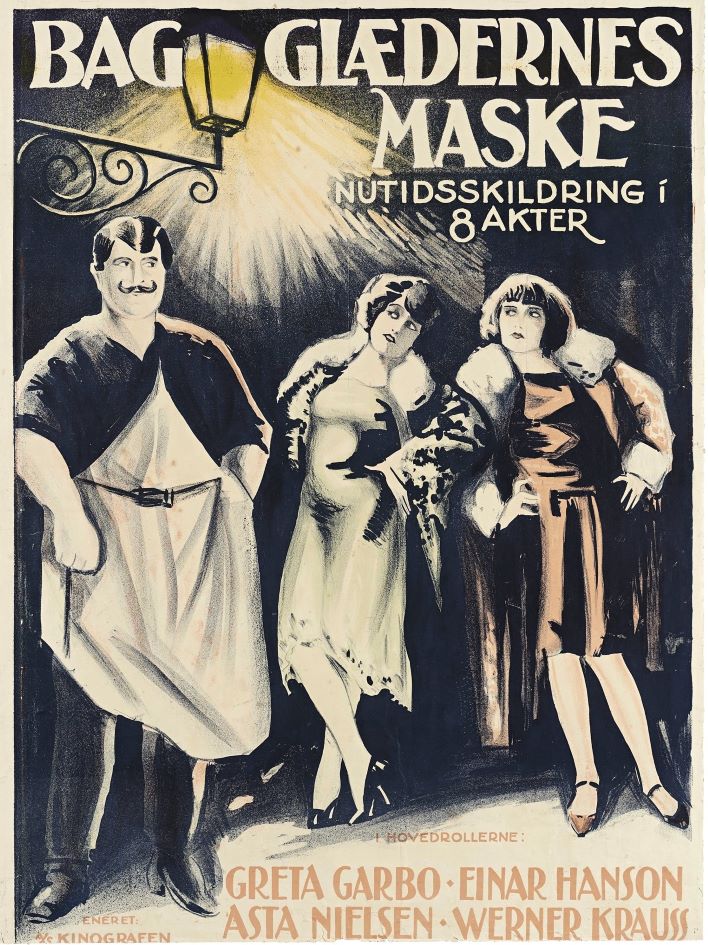

However, not only the film theme, but the film star, too, is the product of capitalist monopolized industry. Not only the art of the theatre, but also the personal charm of the featured players became standardized mass commodities. The closeup, a device peculiar to the films, brought out (much) more than was possible to the legitimate theatre) the most intimate expression of personality. Chaplin’s wistful smile or the passionate glace of Asta Neilson was thrown on the world market as a mass commodity. It was this very popularity of famous film stars that gave them special significance. These stars embodied quite literally definite ideology, which served the purpose of monopolistic capital. Otherwise they would not have been developed by the film industry and could never have achieved stardom. The great fame of certain players of the theatre can be attributed to the fact that they were the very embodiment of ruling class ideology. But these players acted in a variety of plays, in various roles and guises. The influence of their personalities was equally mixed with the influence of the play. But through the magnitude of the film industry the stars became so overwhelmingly familiar and popular that monopolistic capital could not afford to leave their ideological effectiveness to the mere accident of the various roles which they might play. They became fixed personalities that were most suited to forceful expression of the bourgeois ideology. The scenarios are written with these personalities in mind, and the stars play these same characters in all their films. And even when the costumes, the coiffure, the eyebrow style of a Greta Garbo or Asta Nielson are changed, the physiognomy remains the same.

Love

As I pointed out in my last article, love is unquestionably the chief theme of the movies, just as it always has been in literature and the theatre. But love itself varies greatly, in accordance with social relationships and even more so in relation to the ideological purposes of the ruling class. Film romance reveals, throughout, definite policies of monopoly capital. As Ilya Ehrenberg says, this love is produced in a “Dream Factory,” according to a definite prescription and administered like medicine so as to bring definite results. The prescription runs thus: Love, as a force of nature, omnipotent and independent of social relationships; in love, all are equal. In the movies love leads finally either to a rich marriage or, less frequently, to a modest but pure happiness that even the rich can envy. It is the identical recipe used for the romances of pulp literature. The love stories of the film suggest to the petty bourgeoisie a definite standpoint toward the class war, namely, that class differences are not decisive, that there are mightier things which negate them.

The Vamp

In the early movies middle class marriage was holy, not to be tampered with. “The other woman” was the disturber of connubial happiness, was always a wicked, calculating wanton. She was the rouged, cynical, troublemaking mondaine, the misleader, the betrayer of men. That was the “Vamp,” as this type was called in America. Why did this other woman always have to be so wicked? Because in the bourgeois film, marriage symbolized law. Everything, therefore, that endangered the law was sinful and harmful. To prove this to the petty bourgeoisie was the ideological function of the film vamp in times when the security of the capitalist system and its laws was still unassailed. In the crisis period after the world war the confidence of the petty bourgeoisie morality came upon critical times.

The film met this protesting mood by employing every means to counteract this danger as much as possible. So in the films, the prostitute now appeared as heroine. And, of course, this novelty gave rise to any interminable cycle of the same type of film. The greatest film stars such as Pola Negri and Asta Nielson. specialized in playing the glorified, tragic harlot. What ideological policy did this figure conceal? How was she portrayed? In a hypocritical bourgeois society she was shown as the outcast, the despised, but as she was more honest and more capable of loving than others, she was held guiltless of her fate. This mondaine embodied a protest against bourgeois society. But if she finds love is her way back, she is handsomely received…a happy ending and all is again in order.

IN this way the shortcomings of capitalist society, its moral hypocrisies were criticized but not the whole system. Bourgeois society itself not only remained unassailed, but through the tragic sufferings of the trespassing prostitute, made to appear as a lost paradise. The more she aroused the pity of the petty bourgeoisie, so much more valuable seemed the world from which she had been exiled. The prostitute is a “Lumpenproletarian”: a demoralized proletarian. She is unwilling to do battle against the bourgeois society which has produced her. On the contrary, she desires to play a notorious role in it.

I wish in this regard to remark that the tramp or Lumpenproletariat ideology, contained in the film figure, Charlie Chaplin, has for its ultimate aim, the function of apologizing for capitalism. This, in spite of the fact that from the standpoint of this engaging vagabond, society is seen in an absurd and hardly flattering light. In many instances in his films, sharp satirical criticism is heaved at society. But Chaplin’s whole protest consists only of petty thrusts, pin pricks, directed at bourgeois society’s buttocks. And so he disposes of his protest and the protest of his audience. He did not think to change anything by it. On the contrary, his stories seem to denote that one can live quite cheerfully and have one’s little joys in spite of the greatest poverty. And though his stories are melancholy, they are never tragic. Pathetic but good natured resignation was the very core of the Chaplinesque poem, “Such Is Life!” As for those others, the more fortunate ones, let them be, Chaplin bears no ill will, does not grudge them their good fortune.

Criticism as Apology

Such criticism of bourgeois society is at its base an apology. The fascist procedure is to suppress, if it is still possible, the discontented anti-capitalistic mood of the masses, by ignoring it, or to appear to stir it up, simultaneously, however, giving it counter-revolutionary impetus. An example of this is the prostitute, glorified as film heroine. In the years of relative stabilization after the post-war crisis, even the tragic protest of this glorified prostitute was silenced. Pola Negri and Asta Nielson went out of fashion. But with the end of relative stabilization, at the beginning of industrial world crisis, the prostitute again arose as film heroine, in a cycle of Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo films. The prostitute type that Marlene Dietrich presented is less sentimental and much more impudent than the Asta Nielson type. It is in a certain sense more “radical.” It contains much more contempt for bourgeois society. Indeed, without principle, being merely cynically contemptuous, it bespeaks much less respect for custom and law. Indeed, it has no principles to ignore and is in this sense a prepared fascist form of the mondaine heroine; the embodiment of the critical ideology of fascism not yet in power.

Selection of a Lover

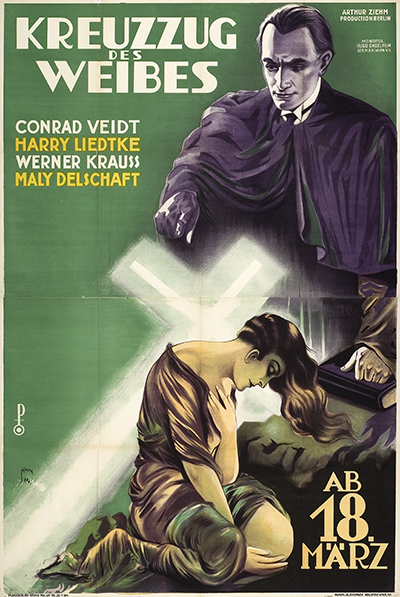

Psylander, Conrad Veidt, Harry Liedtke and Hans Albers–four popular stars…four types of lovers. They represent four different shades of monopoly capitalist ideology and are the products of four different industrial periods in Germany.

Pyslander was one of the first male stars, a product of the Swedish films. He was the correct gentleman, elegant, solid, earnest, manly, his dress and manner sensible and his mode of thinking patterned by custom and tradition; a man possessing poise, a man to marry, a man who could be trusted with a responsible bourgeois position; a hero and the ideological expression of a still confident capitalism.

Conrad Veidt became popular in the post-war period. He was the romantic, expressionistic hero. He typified the escape from reality, which had become insecure. He portrayed Hindoo Mahrajahs and Renaissance cavaliers. He played fantastic artists, adventurers, erratic and mystic beings. In his decadent, unreal expressionistic figure, there arose always, tragic and agonized, an eccentric or abnormal being. Conrad Veidt, the most popular hero of those years, represented flight from reality, lonely suffering and pessimistic defeatism, a world of ruin; a film hero of the German inflation period, of the time of the Spengler philosophy, Decline of the West.

This character of Conrad Veidt suddenly went out of style, even though he continued playing other roles and other personalities. For relative stabilization had arrived. It was no longer necessary to flee from reality to romantic fantasy. It was enough to color or gloss over reality.

HARRY LIEDTKE then became the most popular hero of the German petty bourgeoisie. He was no fantastic figure, no eccentric, but a roguish, laughing, gay, lovable playboy. His occupation and his means of living were never disclosed. He was characterized by dress suit and top hat, jazz, smooth dancing and humorous adventure. He is not solid, strong and elegant like Psylander. This new hero is irresponsible even though he is always found within the frame of society. He shows the petty bourgeoisie (what they themselves wish so much to believe) that life can still be very pleasantly lived in the capitalist world, if one has the money. And that this is not altogether impossible. He portrays heroes without sensibilities and without the slightest ideas regarding moral obligations. For no one respected these obligations any longer. However, Harry Liedtke also went out of style when the short dream of relative stabilization of the capitalist order came to a sudden end and was followed by the new and sharper crisis. The mood of the petty bourgeoisie masses underwent a change. The fascist agitation set in along the whole line and in the film sky a new star arose–Albers. The type, which Hans Albers established and on which his art was standardized, was also the “lover-but of another kind than that of his predecessors.

The protesting mood of an aroused or at the very least, disturbed petty bourgeoisie, mirrored itself in the figure of Albers, always in the same way. This new hero of the film public was no correct gentleman. On the contrary, he was always in conflict with the established order, with “democracy” and its guardians and did not stop at crime. He was no dreamer, like the character masks of Veidt, and no harmless convivial playboy of polite society. He was an outsider, a ruthless go-getter, who recognized neither custom, law nor right. He was a man of direct action, depending for solution of his conflicts on his fists. His psychological effect on the petty bourgeoisie undermined (and that was the purpose) the authority of the existing order (at that time the Weimar Democracy) but without leveling even the bluntest thrust at the capitalist system. The film hero type, Hans Albers, was another product of fascist ideology, when it was still an opposing force, Since fascism is no longer an opposing force, but a ruling power, the hero type that Hans Albers portrayed, has disappeared from the scene, very definitely disappeared. So very much so, that Hans Albers himself had to disappear from Germany. For now even film heroes are compelled to respect Hitler’s laws.

And the case of Albers clearly proves that neither these actors nor perhaps even their directors understood the sense in which they functioned. “They don’t know what they do, but they do it just the same,” says Marx.

The New Theatre continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v1n08-sep-1934-New-Theatre.pdf

PDF of full issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v1n09-oct-1934-New-Theatre.pdf