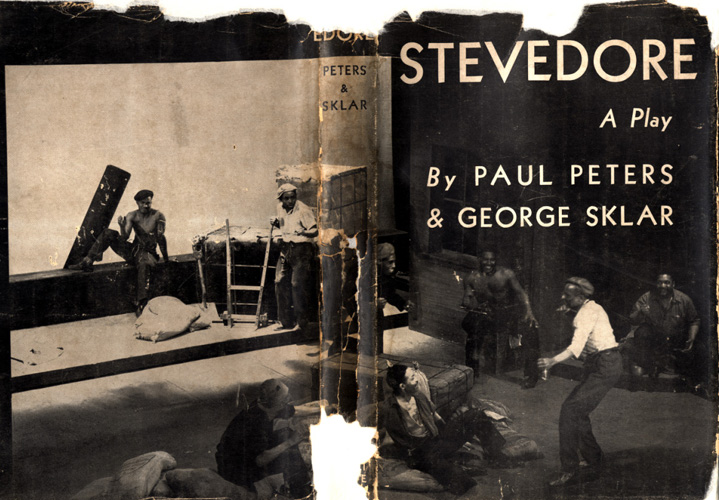

A play that needs a critical revival. Race and class war on the docks, answered by solidarity and barricades; made for the proletariat and produced well enough to compete with Broadway. Michael Gold reviews the revolutionary 30s drama ‘Stevedore’ written by Paul Peters and George Sklar, directed by Michael Blankfort for the Theatre Union.

‘Stevedore’ by Michael Gold from New Masses. Vol. 11 No. 5. May 1, 1934.

THE Theatre Union has just produced its second play, Stevedore, by Paul Peters and George Sklar, and has established the fact that here at last the American revolutionary movement has begun to find itself expressed adequately on the stage.

It was a long time coming, this consummation. The streak of shoddy liberalism that stultified such fellow-travelers’ ventures as the New Playwright’s Theatre is absent from this organization, also the groping amateurism that hung like a doleful curse over many of the first workers’ theatre groups, and blighted their sincere will-to-revolutionary-drama.

Stevedore is not a perfect script or production. The same can be said of the Pulitzer Prize plays of the past ten years. We have as yet no Shakespeares among the American playwrights, nor any Meyerholds or Max Reinhardts among the directors.

But isn’t it a glorious thing to be able to say to bourgeois Broadway: here, from the depths of our poverty, without your resources of high-salaried stars, and publicity men, and hundred-thousand-dollar budgets, and all the rest of the rhinestone-studded machine, working against all the odds of class prejudice and the skepticism of bourgeois critics, the struggling revolutionary theatre has matched you technically?

Yes, many a Broadway crap-shooter in the theatre arts will see Stevedore before its run is over, and will undoubtedly marvel at its last scene, and speculate on how he can make money with it on Broadway. I would advise him not to try the transfusion: the red blood of this passionate giant will not mix with the sickly fluid that flows in the veins of his pampered invalid. It’s not merely a technical trick, Mr. Shyster; the play is a unity, and comes out of a new world. It has something new and of terrific importance to say; and a thousand of your play-carpenters putting their sly brains together could never learn how to say it.

All week a “race riot” has been brewing. The Negro stevedores have been organizing into a union with the revolutionary white workers. The shipping bosses have brought in gangsters to break it up, and as ever, the race question has been used for a red herring.

Some slut of a white woman has been cheating on her husband, and her cheap Romeo wants to break with her. They quarrel, and he smacks her around in good Southern style. She screams hysterically, her husband finds her, and to hide her guilt she says a Negro has attacked her. Immediately there is a round-up of Negro workers, and the shipping bosses are glad to use the newspaper excitement as a means of crushing the young union.

One of the more militant stevedores, Lonnie, is the chief victim of their persecution.

The white organizer saves him from lynching. But the lynching spirit is whipped higher and higher by the boss-gangsters, and finally culminates in a pogrom.

It is here that the play mounts to its magnificent climax. The Negro workers decide to defend themselves. They won’t run away and hide like rabbits. They won’t let the whites kill them with impunity, burn their houses to the ground.

The white organizer arrives. Many of the Negroes will have nothing to do with him; he is white, therefore an enemy. But this cool, strong Leninist leader does not argue; he merely informs them he is going to get the other white workers to help defend the barricade.

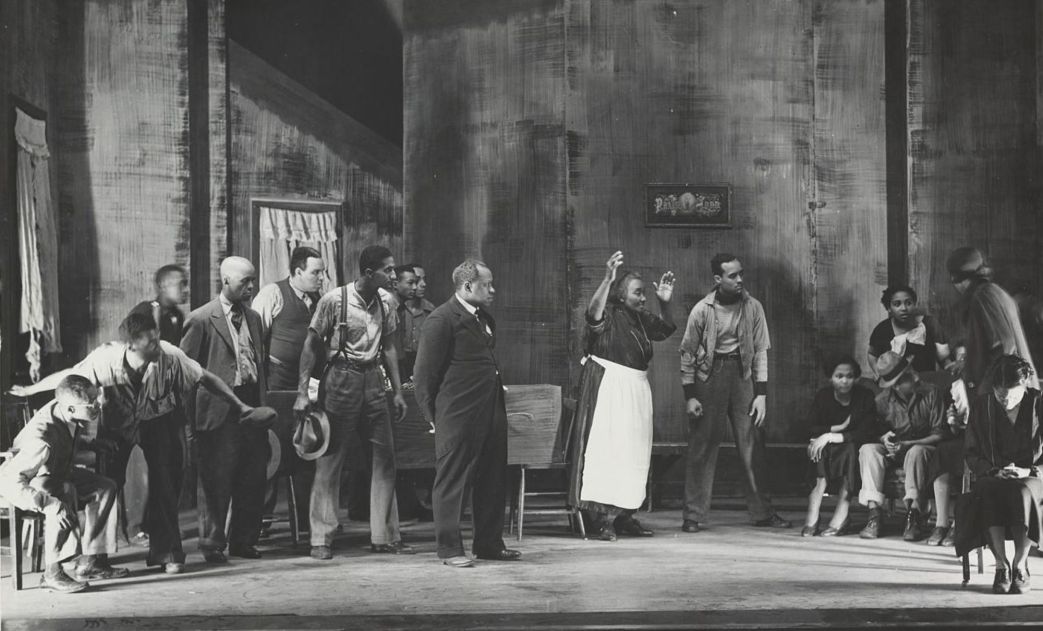

They build a barricade, and arm themselves with bricks, lumps of coal, table legs, and rusty old shotguns. The women boil water to pour on the boss-gangsters. The tension is almost too much to bear, and makes one want to climb over the footlights and grab something, too.

The white boss-gangsters arrive, and yell their foul taunts. But the Negro workers stand their ground like men; and when the gangsters begin shooting, they answer them. It is a tremendous battle scene that is staged here, exciting because it falls into no mock heroics. These are plain, hard-working, good-humored people such as you and I know, and they are fighting for their lives. You want to help them; and when big, lovable, motherly Binnie who runs a lunch-room and bosses the husky stevedores with her spicy tongue, picks up an old gun and pops off one of the gangsters, the audience cheers. It cheers not only because a brute is dead, but because something has happened in the soul of a working-class mother.

Lonnie is killed. But Blacksnake, a powerful giant, assumes the leadership. The white boss-gangsters are winning in this uneven battle of bricks against automatics, when Lem Morris, the union leader, arrives with the white stevedores. And black and white workers unite, for the first time on an American stage, to beat off their common enemy. The boss-gangsters are whipped. “They’re running!” Blacksnake cries joyfully. The play ends, but this powerful image of Negro and white working-class unity is stamped upon one’s mind forever. This is what has happened in life; and this is what must be made to happen. It is really one of those unforgettable experiences in the theatre, the thing that makes the theatre, at its high moments, a supreme teacher of the masses.

But it isn’t only in its climax that this play demonstrates its proletarian power. The work scene on the dock, when the stevedores are piling sugar sacks at midnight, under the glare of electricity, is one of those portraits of a new and vital world that has not reached the stage hitherto. It is real, and the rhythmic work-chants that Paul Peters listened to while working on these same docks in New Orleans, are the pillars of a new poetry. We don’t want the stale Belasco realism on our proletarian stage, that seizes surfaces and hoards soulless objects like a miser. The mechanics of photography are only a means to an end. In this dock scene in Stevedore I believe a start has been made toward a new poetry of working-class life.

The scene in the union office, with its single mimeograph machine, is another sketch full of vistas and instigations. No attempt was made to show the red banners, and pictures of Lenin, and the benches and tables one might find in such a union hall. Instead, there are two workers turning out strike leaflets on a mimeograph. To anyone who knows the revolutionary labor movement, there is something quite touching in this dramatic focus on the mimeograph. Nobody has yet written poems to this humble little machine, this primitive printing press that has called so many workers to demonstrations and picket lines, wounds, danger and victory. It has exposed many a horrible injustice when all the great million-dollar presses were silent; it has traveled secretly in the stokehold of many a ship, it lives in cellars of Hitler Germany, it is the voice of the Alabama sharecroppers and the friend of the coal miners. It was good to see it cast as one of the heroes of a proletarian play, with a glamorous spotlight beating on it, and making it a figure of the imagination.

Stevedore, I repeat, is the most successful attempt at a proletarian drama we have yet had in America. The Theatre Union, with its professionalism, its insistence on technique, its policy of low prices and organized audiences, is the ablest group that has yet at- tempted to build a revolutionary theatre here. The New York workers have begun to realize this, and it is wonderful to see and hear them in this theatre, joining with the actors in nightly demonstrations of feeling. There has never been anything like it in the bourgeois theatre, this mass participation.

A play like Stevedore, and the background in which it has been born, satisfies all of one’s dreams of what a worker’s theatre might be. It has reached that point of skill where it becomes a mass-force, in this case, a call to action for Negro and white solidarity in the class struggle. The issue isn’t clouded, befuddled with literary embroideries as it has been in some of the earlier experiments by fellow-travelers. All is direct, honest, and politically conscious.

Yet this is only a beginning. The rough plastering still shows of the new house. Stevedore is crowded with those set “propaganda” speeches that are really a technical blunder, in any playwright’s play. It is not the con- tent of these speeches that one objects to, but the fact that they are not worked into the action skillfully enough. We are just beginning to learn things in America, and one of the things a crystallizing Marxist criticism of literature is teaching us is that the dialectics of action and imagery are the tools of literature, and not the “idealistic” speeches that are superimposed like decorations; in other words, the structure must be functional, it must teach its own moral. When it fails, all the added words and speeches in the world will only further bungle the matter.

Stevedore has this structure, but did not seem to trust in itself or the intelligence of its audience sufficiently, at various points.

It has another fault; that of its lapses into photographic realism in dialogue. The dream of every playwright is to wed the crude raw truth of life with the shining splendor of poetry. The American theatre has suffered year after year from plays whose dialogue was written by hacks incapable of writing a business letter. The proletarian drama is epic, heroic, satirical, poetic, in its aims and con- tent; it must of necessity find a different speech than the drab prosy naturalism of the Broadway merchants. Writers like Sean O’Casey have indicated what this new speech might be; though, of course, when it is done badly, it becomes pretentious, false, and like the worst of O’Neill, which is worse, everyone admits, than Sam Shipman at his worst.

But we will yet have poetic drama, we will have beauty, and depth, and splendor in our proletarian theatre, even as now we have more strength and meaning than all the Broadway gamblers and racketeers. This is just the beginning.

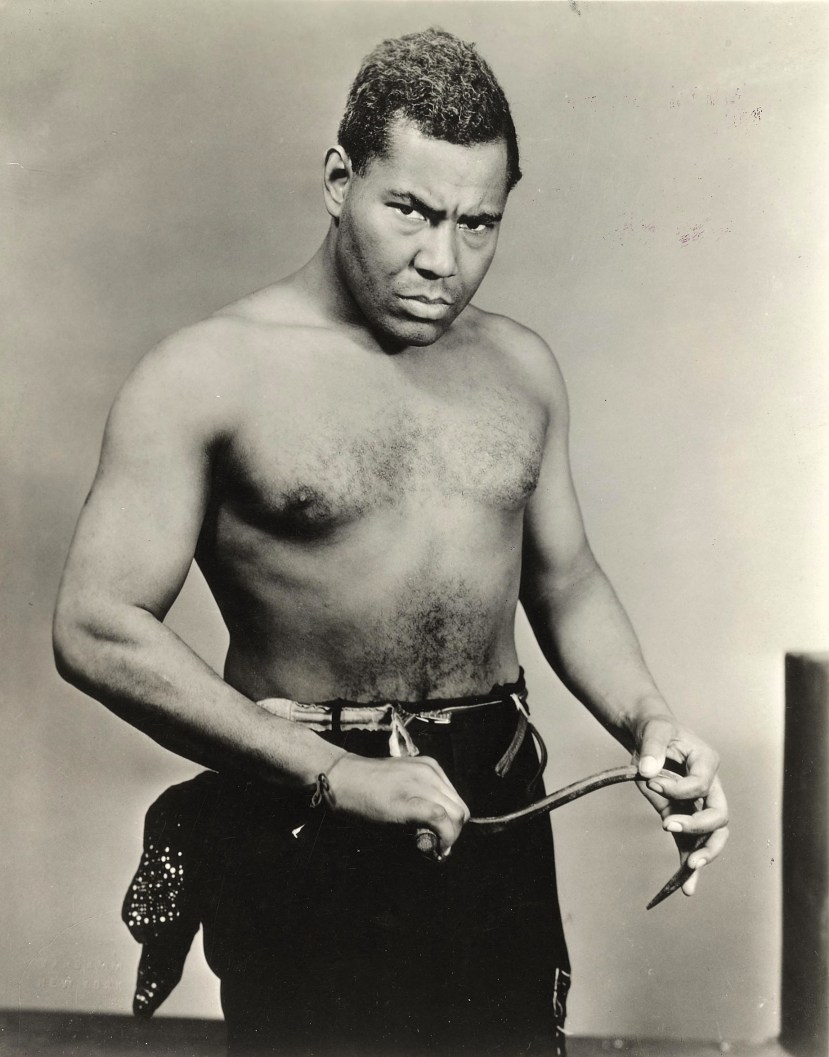

It is a splendid beginning. Michael Blankfort, who directed Stevedore, is a discovery in the theatre. He has handled technical problems that would be bungled by several dozen big Broadway names, and has carried them off with fine imagination. There is a memorable cast, of whom Georgette Harvey and others are well-known, though Rex Ingram, who plays Blacksnake, seems to me on his way to equal fame. He shapes up like another Gilpin or Robeson, in this, his first important role.

Go and see this play, by all means. You can buy a seat for as low as thirty cents, and you will be participating in one of the most exciting adventures that has thus far happened in the world of revolutionary art. It will be something to tell to your Soviet grandchildren; how in 1934, in the depths of the crisis, there was a great surge of worker’s art, and the beginnings of a revolutionary theatre, and a battle play called Stevedore, that brought Negro and white workers into closer brotherhood of mutual understanding.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1934/v11n05-may-01-1934-NM.pdf