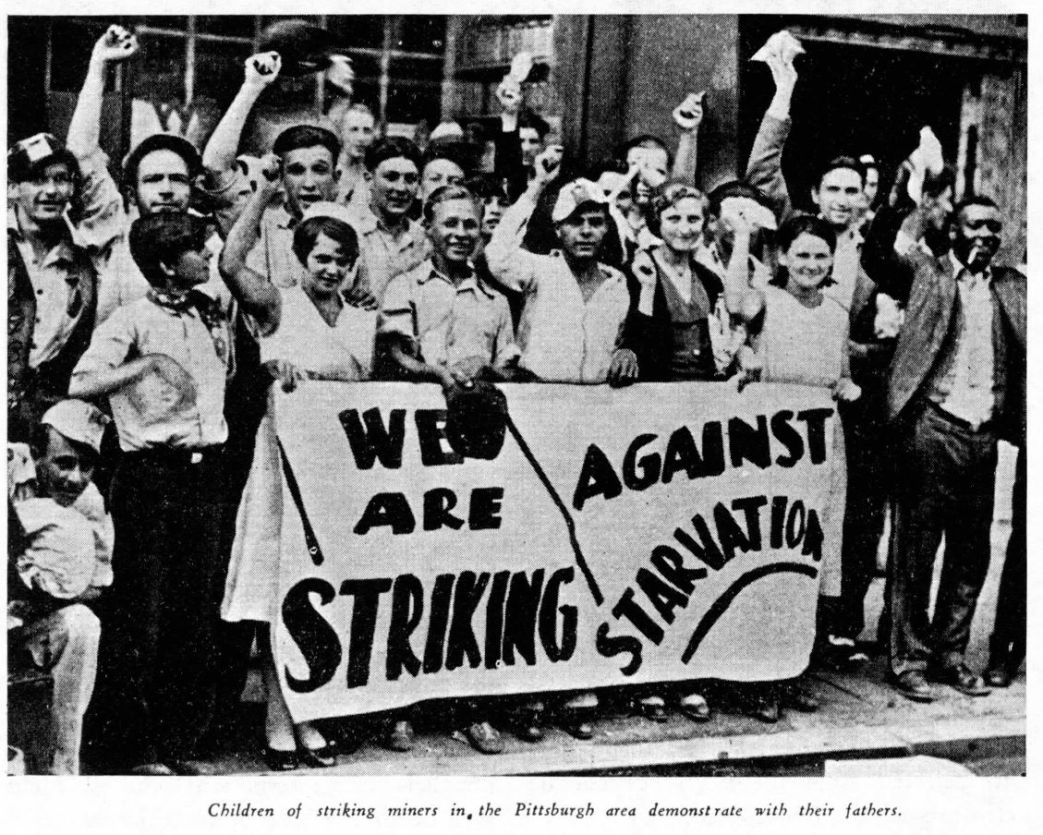

Women have played a role, often central, in every major miners strike in U.S. history. No more so than the rolling 1931 strikes in upper Appalachia.

‘Women Organize to Spread Mine Strike’ from The Daily Worker. Vol. 13 No. 161. July 6, 1931.

Pittsburgh Conference Spurs Auxiliaries.

PITTSBURGH, Pa., July 5. The finest, most militant and concretely organizational conference of working class women, the American labor movement has ever known was held day afternoon when the Women’s Auxiliaries of the National Miners Union held its conference at the Workers Center in Pittsburgh.

“You can’t run a train without tracks,” one miner’s wife said, calling for a clarification of the tasks of the Women’s Auxiliaries and concrete suggestions for carrying them out. Laying the “tracks” was the job accomplished at this conference.

This organization today issued its first regular membership cards and adopted measures to build the woman’s auxiliaries in the mining camps on a permanent functioning basis. An executive committee was established and Helen Lynch of Carnegie elected president. The main report by Mary Smith was enthusiastically adopted.

The conference was followed in the evening by a woman’s mass meeting to mobilize the women of Pittsburgh to cooperate with the Pennsylvania-Ohio Striking Miners Relief Committee in collecting food and money to buy food and tens for the striking miners.

Speaking of the hunger in the coal fields, one woman said, “The best meal we had in months was the buns and coffee on the picket line.” With 40,000 or more strikers’ families to help, the relief committee has not yet been able to care for more than a fraction.

“When we went on strike a week ago Monday,” Mrs. J.C. Jones, Negro woman from McKinleyville, W. Va. said, “Mr. Thomas, the store manager closed down the store for as long as the strike. He threw into the creek all the steaks and pork chops and things. How many of us couldn’t get a dollar in the office while our husbands were working! Now he threw all that away and got guards to keep us from getting into the store and from eating.” Mrs. Jones made a stirring appeal for relief to be sent into her part of the strike field.

Of the 75 delegates representing 33 towns and about 45 mines, all stressed the crying need for immediate relief. They told how far they made what they had at their disposal go, in the soup kitchens.

That the women strongly felt the strike and were playing a courageous, effective part and frequently took the lead where the men hesitated, was made apparent by many colorful and militant speeches by miners’ wives and daughters.

“I’ve never seen so many women at a conference before,” said Mrs. Harkoff of Avella. “And so many Negroes. What’s bringing them? Conditions! The bosses are forcing us to organize!”

When the UMW organizer came to Creighton to try to get a few miners to sign the agreement they were cooking up to sell out the strike the women got wind of it. “The men seemed to think that tis only the big fakers of the UMW that does all the damage and lets the peanut Fagan come into camp and hold meetings to try to get our men to scab,” one Creighton woman declared.

“But when we heard about that meeting in the firehouse, we went right down there, with the kids and all. Some of the men came and knocked at the door. They had it locked. But we women just pushed up the windows and told them, “You’re a bunch of fakers and can’t force us back to work with a million scab agreements!” So the meeting broke up and when the handful of them came out we told them, ‘You’re scabs! Every single man who goes back on us gets his head knocked off! We ain’t wanting any scab agreements signed up for our men who ain’t got no truck with that boss stool pigeon outfit, the UMW! We tell our men, don’t go back to starvation!”

“Men, don’t you go back out on us!” cried the militant daughter of a Maynard, Ohio miner. Julia Proker was bailed out of jail just in time to come to the conference. “The women mean to win this strike. I’ve been in jail several times and I’m not ashamed of it! I’m a coal miner’s daughter, and I’m proud of it!” “Out our way at Provident, the bosses came around and told the men that everything was signed up with the UMW,” she continued. “The next day 15 white and 15 colored fellows were on their way to work, there was 500 of us picketing–they didn’t get into the mine. Again they tried to open the mine and then they quit trying. No chance of our boys going back to 30 cents a ton!” How to make the auxiliaries function more effectively, picketing house to house, organizing work, relief collection and distribution, children’s work, were all dealt with effectively by Caroline Drew. She stressed the permanent work of the auxiliaries which must continue after the strike.

“The company doesn’t only rob the men on rates in the pits, but also in the company stores they charge us twice as much for food. We must boycott company stores and wipe them out. Then we must demand decent houses, not those company shacks, and sanitation. These are some of the things we must keep on working for after the strike,” Drew said.

“Do you remember at the beginning of the strike when visitors came to see our picket lines down at Kinlock that were 1000 strong! They saw the patch—the broken-down, dilapidated company shanties huddled together and fenced in looking like the prison camp it really is! For years Valley Camp Coal Co. didn’t do a thing when they saw the sympathy it was arousing for the strikers, they splashed on a coat of the cheapest white paint.”

To Mrs. Patterson, mother of one of the Scottsboro boys, a pledge for support in the legal lynching were made by the conference.

“I’d now be seeing my boy 12 feet deep, if it wasn’t for the International Labor Defense,” Mrs. Patterson said.

The conference was greeted by Frank Borich in the name of the I National Miners Union, by William Z. Foster for the Trade Union Unity League and Anna Damon, editor of the Working Woman, for her paper.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1931/v08-n161-NY-jul-06-1931-DW-LOC.pdf