A chapter from the second volume of Max Beer’s ‘Social Struggles’ series on the Cathari, a 12th and 13th century Christian heretical movement.

‘The Cathari and Communism’ by Max Beer from Social Struggles in the Middle Ages. Translated by H. J. Stenning. Small, Maynard and Company Publishers, Boston. 1924.

THE CATHARI.

At the turn of the twelfth century the towns of Western and Central Europe were honeycombed by heretical sects. The Balkan Peninsula, North and Central Italy, France, Spain, the whole Rhine valley from Alsace to the Netherlands, a wide tract of Central Germany from Cologne to Goslar, were agitated by sectarian movements, which adopted an antagonistic attitude towards the Church, and were in the course of establishing a new religious and communal life. The masses had been plunged into doubt by the Church, and sought to reorganize their religious, ethical, and social life on a primitive Christian basis. These sects were known by the general name of Cathari (from the Greek katharoi=the pure). From the beginning of the eleventh century we read of decisions of various ecclesiastical synods and sentences of condemnation against the Cathari, who were then known by numerous other appellations, such as Piphilians, textores (weavers), Patarenians, the Poor of Lombardy, Paulicians, the Poor of Lyons, Leonists, Waldensians, Albigensians, Bogumilians, Bulgarians, Arnoldists, Passengers, the Humble, Communiati (Hefele, Council History, 2nd ed. vol. v. pp. 568, 827; Mansi, Sacrorum Concil., Collectio xxii. 477; Pertz, Monumenta Germania, Leges 11, 328). Later their numbers were swelled by the Beghines and the Beghards, who were not heretics originally. These appellations are partly of local, partly of personal origin. The individual heretical movements or organizations were named after the locality where they had their headquarters, or after their most prominent leader, or after their character. Generally speaking, they were Cathari, whence is derived the German term for heretic, ketzer.

The time of origin of the Cathari is the last half of the tenth century. Strange enough, they are first heard of in Bulgaria, where they thrived on the opposition offered by the peasants to the nascent feudalism. Then we hear of the Catharian movement in Western Europe, where it assumed an urban-trading character. From the episcopal synod of Orleans in 1022, where thirteen heretics were accused of “free love,’ and eleven of them were given over to the flames, prosecutions are continuous until the end of the Middle Ages. In the year 1025, heretics were summoned before the Synod of Arras, because they had asserted: the essence of religion is the performance of good works; life should be supported by manual labour; love should be extended to comrades; he who practises this righteousness needs neither sacrament nor church. The movement grew everywhere: in Lombardy, in Languedoc (South France), in Alsace, in the whole Rhine valley, in Central Germany. In 1052 a number of heretics were burnt at Goslar, because they were against the killing of living beings (against war, murder, or even the slaughter of animals). Two decades previously (1030) Catharian heretics were called to account at Montforte (in Turin) because they had sharply rejected the ecclesiastical mode of life, and advocated celibacy, the prohibition of animal slaughter, community of earthly possessions.

It is obvious that an international movement of this kind would be devoid of uniform doctrines, and equally so of uniform practice and policy. In its philosophy, two tendencies can be distinguished: that of Gnostic-Manichean dualism (in strict or moderate forms) and that of Amalrician pantheism. The former, with its more or less sharp antagonism between the two sovereign powers of Good and Evil, of Spirit and Matter, was in a high degree ascetic, morally strict, for it was concerned with subduing the flesh. The followers of the pantheistic tendency, who regarded themselves as partakers of the Holy Spirit, as redeemed from sin, rejected all asceticism and all ties; at least, it seemed that many members of this section lived as supermen, beyond good and evil. Their influence, however, was only intermittent. The great mass of the Catharian sections lived austere lives, and accepted the Gnostic-Manichean philosophy.

The common characteristics of practically all the heretical factions were evangelical poverty, resistance to the secularization of the Church and of Monasticism, the endeavour after a virtuous communal life, the rejection of the sacraments, dogmas, and authorities of official Christianity.

Many of the sects were divided into two classes: the perfect and the faithful. The former class strictly followed the Catharian social ethic: lived ascetic lives, in poverty or communism; the other class, it is true, separated itself from the official Church, but in civil life it pursued the usual vocations and hoped the time would come when all Cathari would be able to live in the light of their social ethics.

Their general policy was of a pacific nature. The Cathari were opposed to all force, and every sort of external coercion; they even regarded the Crusades as human carnage. Only in the direst extremities, when they were threatened with absolute destruction, would they appeal to arms. This was particularly true of the Waldensians, the strongest faction of the Cathari. They all relied upon the eventual triumph of Good by the power of the spirit, of philanthropy and truth.

THE CATHARI AND COMMUNISM

We have no information or documents deriving from the Cathari themselves upon which we can form an opinion of their doctrines, or what is of special interest to us, their attitude towards social and economic ideas, as their writings were confiscated and destroyed by the ecclesiastical and secular authorities. For our knowledge of the Cathari we have to rely upon the statements of those who prosecuted and opposed them, all of whom were supporters of the doctrines of the Church. The inquisitors and judges of the Cathari were bishops, dominicans, and popes, who obviously were chiefly interested in the religious doctrines of the accused, and paid little attention to their views on social and economic questions, just as, conversely, in our day the opponents of socialists and communists have little or no regard for the religious aspect, and lay the greatest stress on the social-economic attitude and aspirations of those whom they oppose. In the Middle Ages religion was the primary consideration, particularly where the Church dispensed justice. Moreover, as theoretical supporters of evangelical poverty and as cenobites, monks could not discover heresy in the fact that the Cathari or sections of them were in favour of a communal life, or a co-operative form of economy. Consequently, the Anti-Catharian writings contain very detailed information concerning their religious views and customs, but scanty details of their social-economic doctrines. All that is certain is that they regarded evangelical poverty as the perfect Christian’s ideal of life, and that they looked on private property and marriage as evils. These doctrines were the consequence alike of their Gnostic-Manichean philosophy, according to which the material and the worldly was the embodiment of evil, and of the high regard they paid to the traditions of the age of primitive Christianity. The Sermon on the Mount was the social-ethical foundation of the heretical mode of life. The injunction to love one’s enemies, the prohibition of swearing, the exhortation to have the tenderest care of their poor and sick brothers, peaceableness, humility, and sexual purity were taken seriously by the Cathari. The Sermon on the Mount was the social-ethical basis of the heretic’s conduct of life. They were antinomian: the sacraments and the ecclesiastical doctrines and precepts generally were regarded by them not as aids but as hindrances to salvation. Their whole attitude towards the Church, the State, and their laws was one of rejection.

We, however, are concerned to learn something about their attitude towards communism. Although the monastic inquisitors were more or less indifferent to the social-economic views and aspirations of heretics, there are indications in the very comprehensive Anti-Catharian literature that the doctrines of communism and natural law were diffused among the Cathari.

A theologian who flourished in the twelfth century, named Alanus (who came either from Lille or from South France), who devoted considerable attention to the doctrines of the Cathari and wrote a work against them (De fide catholica adversus hereticos et Waldenses, Migne, Patrologia T. ccx. 366), observed: “The Cathari say also conjugium obviari legi nature, quia lex naturalis dictat omnia esse communia’’ (that the marriage tie is against the laws of nature, which ordain that all things should be common). A contemporary heresy-hunter adopted another method of discrediting the Cathari. He argued with them: Your communism is only a superficial one, a matter of words; only as agitators are you communists, for in reality there is no equality amongst “you, many are rich, many poor—In vobis non omnia communia, quidam enim plus, quidam minus habent (Everard de Bethune, Liber antiheresis, Opera, vol. xii., Gretser edition 1614, p. 171). Even Joachim of Floris was numbered among the opponents of the Cathari, whom he reproached with promising the people every variety of riches and indulgence. We find a similar anti-communist polemic in an indictment which was drawn up in the years 12101213 in Strassburg (Alsace) against about eighty heretics (Waldensians). The indictment consisted of sixty articles which summarized the false doctrines of the accused persons. Article 15 read: “So that their heresy might gain wider support, they have put all their goods into a common store.” The Waldensians were further accused of sending money to Pickhard, the heretic leader at Milan, and to the Strassburg leader, Johannes, to enable them to strengthen heresy and oppress all priests. Article 16 accused them of free love. The accused leader, Johannes, made answer that the money was collected for the support of the poor, who were very numerous among them; he must, however, repudiate the charge of unchastity as being wholly unfounded.

It is clear that the charge against the heretics did not reside in community of goods in itself, but the alleged object to which the common financial resources were devoted. Here it is pertinent to revert to the above-mentioned accusation against the Cathari of Montforte (1030), which, among other things, states: Omnem nostram possessionem cum omnibus hominibus communem habemus (We have all our possessions in common with all men). The description of the various sects by the Dominican Stephan of Bourbon (died 1261 in Lyons) is also noteworthy. In his curious French Latin he said of the Waldensians that they dampnant omnes terrena possidentes (condemn all possessors of earthly goods). Then there are Communiati, so-called because they say: communia omnia esse debere (all things should be common). Stephan makes merry over the divisions in the sectarian movement, but admits that when it is a question of opposing the Church or monasticism, all heretics stand together (inter se dissident, et contra nos conveniunt) (Etienne de Bourbon, Anecdotes Historiques, Paris, 1877, pp. 278-79, 280-81). Another theologian or monk who exercised his office about the middle of the thirteenth century makes this reference to the Waldensians: “They do not engage in trade, so as to avoid telling untruths, swearing oaths and practising deceptions. They strive not after riches, but are content with necessaries” (quoted by Keller, Die Reformation und die alteren Reformparteien, 1886).

One of the most influential and embittered of heresy-hunters, Bernard of Clairvaux, a Catholic saint, contemporary and vigorous opponent of Abelard and Arnold of Brescia, testified as follows, concerning the social ethics of the Cathari: “If you ask them, none can be more Christian than these heretics; as far as their conduct is concerned, nothing can be more blameless; and their deeds accord with their words. The Cathari deceives no one, oppresses none, strikes none; his cheeks are pale from fasting, he eats not the bread of idleness, and supports himself with the labour of his hands.”

We get a glimpse of the first Waldensians from an account left by the English Prelate, Walter Maps, who officiated as examiner and reporter at the third Lateran Council (international congress of bishops, etc.) held at Rome in 1179, before which a deputation of Waldensians appeared, and were questioned about their teachings, by the Pope’s order (De nugis curialium, p. 65, edition Wright, London, 1850): “ Hii certa nusquam habent domicilia,…circueunt nud pedes, laners induti, nil habentes, omnia sibi communes’”’ (They have nowhere a fixed domicile; they go barefooted, cloth themselves in woolen garments of repentance, have no personal property, but all things in common).

The sect of Humiliati consisted of religious associations of workers, who laboured in common. From these reports and from the whole spiritual outlook of the Cathari, the conclusion may be drawn that this movement whole-heartedly espoused the ideals of the primitive Christian communities, rejected on principle private property and the social order based upon it, and aimed at a communal life which would enable them to subdue the material and to develop the virtues which their philosophy enjoined.

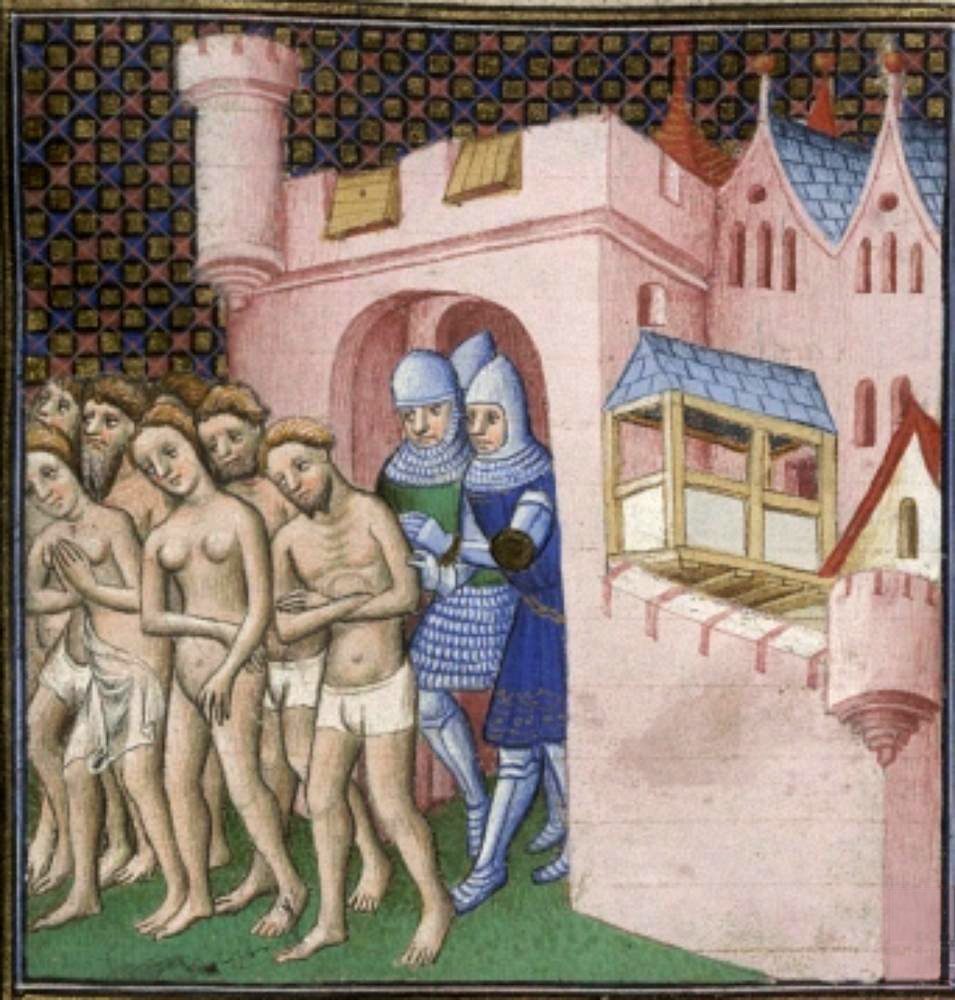

It is doubtful whether the Cathari ever possessed extensive communistic institutions. In fact, they had no opportunities to put their ideas into practice, for, as soon as their movement assumed any dimensions which would have enabled them to proceed to the practical solution of their problems, Church and State embarked on a policy of ruthless persecution, the fires were lighted, dungeon and sword slew thousands upon thousands of Cathari. They died in masses for their convictions. In moving language the Cathari of Cologne described their situation in the middle of the twelfth century, when they were being called to account before the episcopal judges: “We poor Christians are unsettled and wander from town to town, like lambs in the midst of wolves (de civitate in civitatem fugientes, sicut oves in medio luporum). We suffer persecution like the apostles. But you love the world and have made your peace with it.” (Eberwin, Epistola ad S. Bernardhum, Migne, T. clxxxii. p. 676).

It is obvious that under such vicissitudes of life the realization of communism was out of the question. The learned Church historian, Dollinger, who studied all the documents pertaining to the history of the Sects during several decades (author of the work, Contributions to the History of the Sects, of which the second large volume consists of documents collected from the great libraries), writes: “Every heretical doctrine which arose in the Middle Ages had explicitly or implicitly a revolutionary character, that is, in the measure that it attained to a commanding position, it threatened to dissolve the existing political order and to effect a political and social transformation. Those Gnostic sects, the Cathari and the Albigenses, which specially provoked the harsh and ruthless legislation of the Middle Ages, and had to be put down in a series of bloody struggles, were the Socialists and Communists of that time. They attacked marriage, the family, and property. Had they triumphed, a general upheaval and a relapse into barbarism and heathen licentiousness would have been the consequence. Everyone acquainted with history knows that there was no place whatever in the European world of that time even for the Waldenses, with their principles touching oaths and the right of the State power to inflict punishment.” (Kirche und Kirchen. Papsttum und Kirchenstaat, 1861, p. 51). Déllinger’s words are inspired by an apologetic purpose. He wrote in support of Catholic authority. But he overlooked the fact that the strict application of the social ethics of the Gospels, the Sermon on the Mount, and the primitive Christian communities would also have rendered a feudal or bourgeois world impossible.

In essence, monasticism was a theoretical admission that the bourgeois world was incompatible with the Gospel of Christ. This is at least true of the first centuries of monasticism. And when the monasteries became secularized and broke faith with the Gospel, the gap was filled by the Cathari, the Franciscan Left Wing, the Spiritualists, the Waldenses, etc. In any case, Ddllinger’s expression of opinion is a further proof of the communistic tendencies among the Cathari. The disappointment caused by the failure of the Church called the monasteries into existence, and the failure of monasticism was followed by the Cathari. So long as primitive Christianity held sway, monasticism did not exist, nor was it needed. So long as monasticism cultivated the evangelical virtues, there was no Catharist movement. These phenomena were created not post hoc but propter hoc; they did not follow each other in point of time, but were related as cause and effect, although this process was powerfully aided by the economic conditions.

Social Struggles in the Middle Ages by Max Beer. Translated by H. J. Stenning. Small, Maynard and Company Publishers, Boston. 1924.

PDF of original book: https://books.google.com/books/download/Social_Struggles_in_the_Middle_Ages.pdf?id=7AYZAAAAMAAJ&output=pdf