Rebuilding a financial system on a new basis was a fundamental, and unenviable, task of the revolution. A valuable history of the first two years of work of the Commissariat of Finance in Soviet Russia. The first Commissar of Finance was Ivan Skvortsov-Stepanov, with the portfolio held by Nikolai Krestinsky when this report was written for Economic Life, the premiere Soviet journal of economy.

‘The People’s Commissariat of Finance, Policy and Activity 1917-1919’ from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 2. No. 9 February 29, 1920.

Economic Life, November 7, 1919.

I.

AS the Soviet Government was first organized a number of purely financial questions arose which necessitated the utilization of the services of the old financial-administrative apparatus in the form in which it existed prior to the October Revolution. It is quite natural that the first period of work in the domain of finance, that is, between the October Revolution and the Brest-Litovsk peace, had of necessity to be marked by efforts to conquer that financial apparatus, its central as well as its local bodies, to make a study of its functions and somehow or other adapt it to the requirements of the time.

While in the domain of the Soviet Government’s economic and general policy, this period has been marked by two most far-reaching and important changes which, strictly speaking, had been prepared prior to the October Revolution—the nationalization of banks and the annulment of the government debt,—the financial policy, in the narrow sense of the word, did not disclose any new departures, not even the beginnings of the original constructive work.

Gradually taking over the semi-ruined pre-revolutionary financial apparatus, however, the Soviet Government was compelled to adopt measures for the systematization of the country’s finances in their entirety.

This second period in the work of the People’s Commissariat for Finances (approximately up to August, 1918) also fails to show any features of sharply marked revolutionary change. From the very beginning the authorities have been confronted with a chaotic condition of the country’s financial affairs. All this, in connection with the large deficit which became apparent in the state budget, compelled the Commissariat of Finance to concentrate its immediate attention on straightening the general run of things and thus preparing the ground for further reforms.

In order to accomplish the systematization of the financial structure, the Government had to lean for support on the already existing unreformed institutions, i.e., the central departments of finance, the local administrative-financial organs—the fiscal boards, tax inspection, treasuries, excise boards,— and, more particularly, the financial organs of the former local institutions for self-government (Zemstvos and municipalities).

Such a plan of work seemed most feasible, since the apparatus appeared suitable for fulfilling slightly modified functions; but the local government was not yet sufficiently crystallized or firmly established, neither was any stable connection established between that local government and the central bodies.

Under such circumstances the old institutions, which by force of habit (inertia) continued to work exclusively at the dictate of and in accordance with the instructions from the central bodies seemed to be the most convenient and efficient means of carrying out measures which the central authorities had planned to straighten out the general disorder prevailing in financial affairs.

However, this idea soon had to be discarded. The local Soviets insofar as they organized themselves and put their executive organs into definite shape, could not and did not have the right to neglect the work of the old financial organs functioning in the various localities, since the Soviets represented the local organs of the central government as a whole and since it was upon them that the responsibility for all the work done in the localities rested.

Under such conditions friction was inevitable. In accordance with the principles of the old bureaucratic order the local financial institutions neither knew nor had any idea of subordination other than the slavish subordination to the central authorities which excluded all initiative on their part.

Under the new conditions these local financial institutions were to constitute only a small component part of the local Soviets. Acute misunderstanding of the local authorities among themselves, and between the local and central authorities on the subject of inter-relations among all of these institutions have demonstrated the imperative necessity for reorganization. With this work of reforming the local financial organs (September, 1918) a new period opened,—the third period in the activity of the Commissariat, which coincides with the gradual strengthening of the general course of our economic policy. The economic policy definitely and decisively occupies the first place which duly belongs to it, while the financial policy, insofar as it is closely bound up with the economic policy, is being regulated and directed in accordance with the general requirements of the latter.

II.

The financial policy of Soviet Russia was, for the first time, definitely outlined by the Eighth (March, 1919) Convention of the Russian Communist Party.

The Eighth Party Convention clearly and concretely stated our financial problems for the transition period, and now our task consists in seeing to it that the work of the financial organs of the republic should be in accord with the principles accepted by the party.

These principles, briefly, are as follows: (1) Soviet Government State monopoly of the banking institutions; (2) radical reconstruction and simplification of the banking operations, by means of transforming the banking apparatus into one of uniform accounting and general bookkeeping for the Soviet Republic; (3) the enactment of measures widening the sphere of accounting without the medium of money, with the final object of total elimination of money; (4) and, in view of the transformation of the government power into an organization fulfilling the functions of economic management for the entire country,—the transformation of the pre-revolutionary state budget into the budget of the economic life of the nation as a whole.

In regard to the necessity for covering the expenses of the functioning state apparatus during the period of transition, the program adopted outlines the following plan: “The Russian Communist Party will advocate the transition from the system of levying contributions from the capitalists, to a proportional income and property tax; and insofar as this tax outlives itself, due to the widely applied expropriation of the propertied classes, the government expenditures must be covered by the immediate conversion of part of the income derived from the various state monopolies into government revenue.”

In short, we arrive at the conclusion that no purely financial policy, in its pre-revolutionary sense of independence and priority, can or ought to exist in Soviet Russia. The financial policy plays a subsidiary part, for it depends directly upon the economic policy and upon the changes which occur in the various phases of Russia’s political and economic order.

During the transitionary period from Capitalism to Socialism the government concentrates all of its attention on the organization of industry and on the activities of the organs for exchange and distribution of commodities.

The financial apparatus is an apparatus subsidiary to the organs of production and distribution of merchandise. During all of the transitional period the financial administration is confronted with the following task: (1) supplying the productive and distributive organs with money (symbole), as a medium of exchange, not yet abolished by economic evolution, and (2) the formation of an accounting system, with the aid of which the government might materialize the exchange and distribution of products. Finally, since all the practical work in the domain of national and financial economy cannot and should not proceed otherwise than in accordance with a strictly-defined plan it is the function of the financial administration to create and compile the state budget in such a manner that it might approximate as closely as possible to the budget of the entire national economic life.

In addition to this, one of the largest problems of the Commissariat of Finance was the radical reform of the entire administration of the Department of Finance, from top to bottom, in such a manner that the fundamental need of the moment would be realized most fully—the realization of the dictatorship of the proletariat and the poorest peasantry in the financial sphere.

III.

The work of the financial institutions for the solution of the first problem of our financial policy, i.e., the monopolization of the entire banking business in the hands of the Soviet Government, may be considered as having been completed during the past year.

The private commercial banks were nationalized on December 14, 1917, but even after this act there still remained a number of private credit institutions. Among these foremost was the “Moscow People’s Bank” (Moscow Narodny Bank, a so-called cooperative institution). There were also societies for mutual credit, foreign banks (Crédit Lyonnais, Warsaw Bank, Caucasian Bank, etc.), and private land banks, city and government (provincial) credit associations.

Finally, together with the Moscow Narodny Bank there existed Government institutions—savings banks and sub-treasuries. A number of measures were required to do away with that lack of uniformity involved, and to prepare the ground for the formation of a uniform accounting system.

A number of decrees of the Soviet of People’s Commissaries and regulations issued by the People’s Commissariat of Finance has completed all this work, from September, 1918, to May, 1919.

By a decree of October 10, 1918, the Societies for Mutual Credit were liquidated; three decrees of December 2, 1918, liquidated the foreign banks, regulated the nationalization of the Moscow Narodny (Co-operative) Bank and the liquidation of the municipal banks; and finally, on May 17, 1918, the city and state Mutual Credit Associations were liquidated. As regards the question of consolidating the treasuries with the offices of the People’s Bank, this has been provided in a decree issued on October 31, 1918; the amalgamation of the savings banks with the People’s Bank has been effected on April 10, 1918.

Thus, with the issuance of all of the above mentioned decrees, all the private credit associations have been eliminated and all existing Government Credit Institutions have been consolidated into one People’s Bank of the Russian Republic. The last step in the process of reform was the decree of the People’s Commissariat of Finance which consolidated the State Treasury Department with the central administration of the People’s Bank, this made possible by uniting the administration of these organs, the enforcement of the decree concerning the amalgamation of the treasuries with the People’s Bank.

The decree of the People’s Commissariat of Finance of October 29, 1918, issued pursuant to Section 902 of rules on state and county financial organs—practically ends the entire reform of uniting the treasuries with the institutions of the bank.

This reform constitutes the greatest revolutionary departure, in strict accordance with the instructions contained in the party program. Prior to the completion of this reform, the old pre-revolutionary principle continued to prevail—that of opposition of the State Treasury to the State Bank, which was independent financially, having its own means, operating at the expense of its capital stock, and acting only as a depository for the funds of the State Treasury and as its creditor. Insofar as the new scheme of our financial life has been realized, this dualism has finally disappeared in the process of realization of the reform. The bank has now actually become the only budget-auditing savings account machinery of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic. At the present moment it is serving all the departments of state administration, in the sense that it meets all the government expenditures and receives all the state revenue. It takes care of all accounting between the governmental institutions, on the one hand, and the private establishments and individuals, on the other. Through the hands of the People’s Bank pass all the budgets of all institutions and enterprises, even the state budget itself; in it is concentrated the central bookkeeping which is to unify all the operations and to give a general picture of the national-economic balance.

Thus, we may consider that the fundamental work, i.e., “the monopolization of the entire banking business in the hands of the Soviet Government, the radical alteration and simplification of banking operations by means of converting the banking apparatus into an apparatus for uniform accounting and general bookkeeping of the Soviet Republic” — has been accomplished by the Commissariat of Finance.

IV.

As regards the carrying into practice of a number of measures intended to widen the sphere of accounting without the aid of money the Commissariat of Finance has, during the period above referred to, undertaken some steps insofar as this was possible under the circumstances.

As long as the state did not overcome the shortage of manufactured articles, produced by the general dislocation of industrial life, and so long as it could arrange for a moneyless direct exchange of commodities with the villages, nothing else remains for it than to take, insofar as possible, all possible steps to reduce the instances where money is used as a medium of exchange. Through an increase of moneyless operations between the departments, and between the government and individuals, economically dependent upon it, the ground is prepared for the abolition of money.

The first step in this direction was the decree of the Soviet of People’s Commissaries of January 22rd, 1919, on accounting operations, containing regulations on the settling of merchandise accounts (products, raw material, manufactured articles, etc.) among Soviet institutions, and also among such industrial and commercial establishments as have been nationalized, taken over by the municipalities, or are under the control of the Supreme Council of National Economy, the People’s Commissariat for Food Supply, and provincial Councils of National Economy and their sub-divisions.

In accordance with this decree, the above mentioned accounts are to be settled without the medium of currency by means of a draft upon the state treasury for the amount chargeable to the consuming institution, and to be credited to the producing institution or enterprise. In the strict sense, the decree establishes a principle, in accordance with which any Soviet institution or governmental enterprise requiring merchandise, must not resort to the aid of private dealers, but is in duty bound to apply to the corresponding Soviet institutions, accounting, producing or distributing those articles. Thus, it was proposed, by means of the above mentioned decree, to reduce an enormous part of the state budget to the mere calculation of interdepartmental accounts, incomes on one side and expenditures on the other. In other words, it becomes possible to transact an enormous part of the operations without the use of money as a medium of exchange.

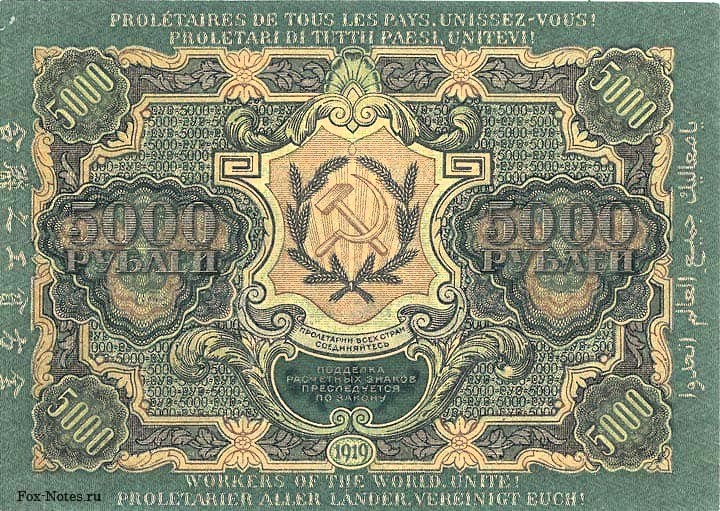

As regards the policy of the Commissariat of Finance in the domain of the circulation of money, one of the most important measures in this respect was the decree of the Soviet of People’s Commissaries of May 15th, 1919, on the issue of new paper money of the 1918 type.

This decree states the following motive for the issue of new money: “this money is being issued with the object of gradually replacing the paper money now in circulation of the present model, the form of which in no way corresponds to the foundations of Russia’s new political order, and also for the purpose of driving out of circulation various substitutes for money which have been issued due to the shortage of paper money.”

The simultaneous issue of money of the old and new type made it impossible for the Commissariat of Finance to immediately commence the exchange of money, but this in no way did or does prevent it from preparing the ground for such exchange, in connection with the annulment of the major part of the old money in a somewhat different manner. Creating a considerable supply of money of the new model (1918) and increasing the productivity of the currency printing office, the Commissariat is to gradually pass over to, in fact has already begun, the issue of money exclusively of the new type. A little while after the old paper money has ceased to be printed, the laboring population, both rural and urban as well as the Red Guards, all of whom are not in a position to accumulate large sums, will soon have none of the old money. Then will be the time to annul the money of the old type, since this annulment will not carry with it any serious encroachment on the interests of the large laboring masses.

Thus, the issue of new money is one of the most needed first steps on the road to the preparation of the fundamental problem, that is the annihilation of a considerable quantity of money of the old type, reducing in this way the general volume of the mass of paper money in circulation.

We thus see that here, too, the Commissariat of Finance followed a definite policy. It goes without saying that from the point of view of Socialist policy all measures in the domain of money circulation are mere palliative measures. The Commissariat of Finance entertains no doubts as to the fact that a radical solution of the question is possible only by eliminating money as a medium of exchange.

The most immediate problem before the Commissariat of Finance is undoubtedly the accomplishment of the process which has already begun, namely, the selection of the most convenient moment for the annulment of the old money. As regards the part which currency generally (at this moment of transition) plays, there can be no doubt that now it is the only and therefore inevitable system of financing the entire governmental machinery and that the choice of other ways in this direction entirely depends upon purely economic conditions, i.e.: mainly upon the process of organization and restoration of the entire national economy as a whole.

V.

The explanatory note, attached to the budget for July to December, 1918, thus depicts our future budget: “when the Socialist reconstruction of Russia has been completed, when all the factories, mills and other establishments have passed into the hands of the government, and the products of these will go to the government free directly and when the agricultural and farming products will also freely flow into the government stores either in exchange for manufactured articles or as a duty in kind…then will the state budget reflect not the condition of the monetary transactions of the state treasury…but the condition of the operations involving material values, belonging to the State, and the operations will be transacted without the aid of money, at any rate without money in its present form.”

It is clear that at present the conditions are not yet fully prepared for the transition to the above stated new form of state budget. But, in spite of this, the Commissariat of Finance has taken a big step forward in the direction of reforming our budget.

The budget of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic, adopted by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee on May 20, 1919, represents the first experiment in effecting a survey not so much of the financial activity of the state, as of its economic activity, even though it is as yet in the form of money.

In the work of reforming the budget, the Commissariat of Finance has come across two obstacles which bare a heritage of the pre-revolutionary time; the division of revenue and expenditures into federal, state and local, and the hesitation on the part of some to include in the budget all the productive and distributive operations of the Supreme Council of National Economy and of the Commissariat for Food Supply. Both the first and second obstacles have been somehow surmounted, and the above mentioned (third) revolutionary budget is already different from the two preceding budgets in many peculiarities which are very typical. These consist in a complete account of all production and distribution which the state has taken upon itself. This experiment is by no means complete, but the achievement would nevertheless be judged as considerable; the concrete conditions for making out the budget, as is stated in the explanatory note, have already made it possible to enter upon the road of accounting for the entire production and distribution of the nation and that thereby the foundation has been laid down for the development of the budget in the only direction which is proper under the present conditions.

The budget of the first half of 1919 has followed the same fundamental principles for the construction of the state budget, by including the expenditures of the entire state production and distribution as well as of the sum total of the revenues in the form of income from the productive and distributive operations of the state. In other words, this budget for the first time takes into account all the transactions of the Supreme Council of National Economy and of the Commissariat for Food Supply.

The further development of the budget will be directed toward working out the details of this general plan and will in particular differentiate the two groups of revenue and expenditure: (1) direct, actual money received or paid and (2) transactions involved in the accounting of material and labor, but not involving any actual receipts of money, or requiring any actual disbursements in money.

VI.

In the field of taxation one must bear in mind first that the entire question of taxation has been radically changed with the beginning of Communist reconstruction.

Under the influence of the combined measures of economic and financial legislation of the Republic, the bases for the levying of land, real estate, industrial taxes, taxes on coupons, on bank notes, on stock, stock exchange, etc., completely disappeared, since the very objects of taxation themselves have become government property. The old statutes regulating the income tax (1916), which has not as yet been abolished, was in no way suitable to the changed economic conditions. All this compelled the Commissariat of Finance to seek new departures in the field of taxation.

However, it was impossible to give up the idea of direct taxation prior to the complete reformation of the tax system as a whole. Our work of Communist reconstruction has not been completed; it would be absurd to exempt from taxation the former capitalists as well as the newly forming group of people who are striving to individual accumulation. This is why the system of direct taxation, which has until recently been in operation, was composed of fragments of the old tax on property and of the partly reformed income tax law. However, beginning with November, 1918, to this old system there were added on two taxes of a purely revolutionary character which stand out apart within the partly outgrown system— “taxes in kind” (decree of October 30th, 1918), and “extraordinary taxes” (November 2, 1918).

Both decrees have been described as follows by Comrade Krestinsky, Commissary of the Finance, at the May session of the financial sub-divisions:

“These are decrees of a different order, the only thing they have in common is that they both bear a class character and that each provides for the tax to increase in direct proportion with the amount of property which the taxpayer possesses, that the poor are completely free from both taxes, and the lower middle class pays them in a smaller proportion.”

The extraordinary tax aims at the savings which remained in the hands of the urban and larger rural bourgeoisie, from former times. Insofar as it is directed at non-labor savings it cannot be levied more than once. As regards the taxes in kind, borrowing Comrade Krestinsky’s expression, “it will remain in force during the period of transition to the Communist order until the village will from practical experience realize the advantage of rural economy on a large scale compared with the small farming estate, and will of its own accord, without compulsion, en masse adopt the communist method of land cultivation.”

Thus, the tax in kind is a link binding politically the Communist socialized urban economy and the independent individual petty agricultural producers.

Such are the two “direct” revolutionary taxes of the latest period. In regards to the system of pre-revolutionary taxes, the work of the Commissariat of Finance during all of the latest period followed the path of gradual change and abolition of the already outgrown types of direct taxation and partial modification and adaptation to the new conditions of the moment, of the old taxes still suitable for practical purposes.

At the present moment the Commissariat of Finance has entered, in the domain of direct taxation reforms, upon the road toward a complete revolution in the old system. The central tax board is now, for the transitionary period, working on a project of income and property taxation, the introduction of which will liquidate all the existing direct taxes, without exception. The resulting sole tax will be of such nature as to cover not only income, but also accumulations, so that every citizen will have to yield all his hoardings above a fixed sum.

In closing this review of the activity of the Commissariat of Finance during the two years of its existence, one must note briefly the great purely organizational work, conducted by it on national as well as a local scale.

The reform has been definitely directed towards simplifying the apparatus and reducing its personnel as far as possible.

Finally, with this reform, the Commissariat of Finance has been organized in the following manner: The central office, the central budget-accounting board (former People’s Bank and Department of State Treasury) and, finally, the central tax board (former Department of Assessed Taxes, and of Un-Assessed Taxes). Upon the same pattern are also being modeled the local financial bodies.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v1v2-soviet-russia-Jan-June-1920.pdf