Leonora O’Reilly, Organizer of the National Women’s Trade Union League, writes about one of the most remarkable strikes of its time. The strike in Kalamazoo, Michigan of women and girl corset workers against systemic sexual harassment, assault, and exchange by managers of the factory. Defying an injunction to return to work, women were jailed for refusing to be assaulted.

‘The Story of Kalamazoo’ by Leonora O’Reilly from Life and Labor. Vol. 2 No. 8. August, 1912.

Where is Kalamazoo? What is Kalamazoo? How Does Kalamazoo earn its daily bread?

Perhaps you, like I, thought that Kalamazoo was a nickname for the place to which we send all our bothers with a, “O, go to Kalamazoo.”

If you love your fellow workers don’t send any of your troubles to Kalamazoo just now. Poor Kalamazoo has trouble enough of its own, labor troubles–serious labor troubles–the kind of troubles that arise in every industrial center where they strive to “grow rich quick” no matter who pays the bills.

Sad as is the story of the labor struggle in Kalamazoo today, the future may bless the labor agitators who undertook to spread the light and teach the working people of Kalamazoo that a city’s greatest wealth is its people, especially its working people: for on their health–physical, mental and moral–depends the health of the community.

Kalamazoo is a beautiful little town in Michigan. Twenty-five thousand people call it their home town. It thrives by the industry of its people.

You may have heard of Kalamazoo celery. It has a national reputation for its whiteness and goodness. Just now another industry, the one of which I write, the Kalamazoo Corset Co., is making for itself a pretty black record.

A little more than a year ago the corset workers who make the American Beauty and the Madam Grace corset, combined to sell their labor collectively; that is, they formed a union. They prepared a price list, presented their contract, had it signed by the employers and went to work as union workers. During the year, through the educational work of the union, they learned to aspire to larger results from organization than an increase in wages–they began to hope that they might wipe out the abuses, injustices and evil practices tolerated by the management of the corset company. Accordingly in their second agreement they drew attention to these conditions. The corset company, without considering the contract, refused to have any further dealings with the union and promptly discharged twelve of the most active members of the union. This led to a general walk out. A strike was declared. This strike has brought to the public attention some of the most serious problems of our industrial life today. Here are some of the facts in the case:

Over twenty years ago, in the heart of a beautiful western town, an industry needing the skill of women’s fingers, started to manufacture its corsets. Twenty years ago Kalamazoo was a small but growing town.

Small growing towns have their attractions for business. Rents are cheap for one thing. Growing towns mean there will be young people, perhaps plenty of young girls looking for employment. These, too, will be cheap.

Cheap rent and cheap labor will bring large profits on money invested. Add to this an unscrupulous management where small wages are paid for useful labor in the factory–while the wages of sin it offers to the young girls who will pay “the price” are alluring, first she receives good and easy work while in the factory, with all the little attentions which can make the hard dull day of the factory girls more bearable–add to this, that for the favored ones there is always a chance for a gay time somewhere at night after the day’s work.

Facts Brought to Light.

Such were the facts brought to light by these striking corset workers of Kalamazoo. When the strike started the older women thought this was their opportunity to start a moral as well as a sanitary house cleaning in one shop in Kalamazoo. They believed that the whole people would rise up to protect them.

The world is a big place, people are slow to action and these brave women were served with a blanket injunction for their pains. By this injunction the corset company expected to silence the women as well as prevent them from picketing the shop.

It did neither. The girls told their story to whomsoever would listen.

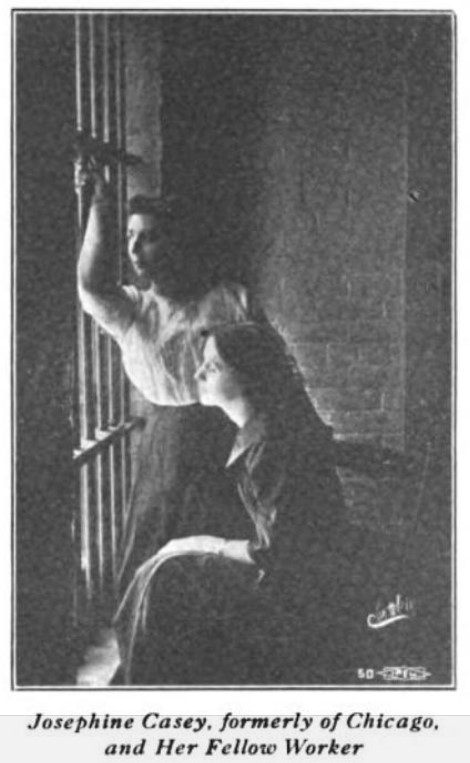

The two girls in the illustration were sent to jail for picketing after the injunction was served on them. The stronger one of these girls served twenty days in prison; the frailer girl served thirty-six days.

Look long and well at this picture. Study it closely. It tells the story of labor’s struggle and labor’s promises.

Today it is Kalamazoo’s. Tomorrow it may be your own home town.

Keep the picture beside you as you work. Get its meaning by heart.

These two girls dared to break an injunction to obey what they believed to be a higher law.

They believed they were obeying a higher law when they tried to keep other women from going to work in a factory where the conditions had grown too vile for words. You will see that the one girl’s strength is almost spent–but you will also see that she is supported by her sister who is strong. Together they look beyond the bars of their prison cell out into the light.

This light to them is the symbol of a better day which will come to all workers when all workers, like this handful of brave girls, live by the doctrine that “Goodness is alone eternal. Evil was not made to last.”

By daring to picket in spite of injunction, by going to jail and refusing bail, because they believed they had done no wrong, these girls succeeded in waking up an inert public conscience. In other words these striking corset workers taught Kalamazoo it must answer when the people asked it, “How do you earn your daily bread and keep, Kalamazoo?”

Many of the good people of the pretty little town were astonished by the tales of horror so close beside their doors.

Said they: “Is it possible that vice lives so close to the heart of a respectable industry in our Kalamazoo?”

Affidavits were drawn up and sworn to by the workers to prove the truth of their stories.

What could Kalamazoo do? Kalamazoo like every other community today, has a group of people who understand that labor is the foundation of life. Therefore a legitimate question to put to a person or a community is, “How do you earn your daily bread?”

If, as a community, in the earning of your prosperity you have sacrificed the life of the workers or made light of the morality of its young women–woe be to you as a community.

At last Kalamazoo got together a committee of good people with a civic sense of righteousness. The committee is known as the Committee of Sanitation and Morals. Much that is good has been done by the committee. After many days of labor to bring about an understanding, an agreement was drawn up by the committee to try to satisfy all parties in this struggle.

The strikers felt that their side had been badly treated in this agreement. They voted it down, saying starvation for a principle was better than peace at such a price.

After two weeks more of struggle, again friends of labor urged the strikers to end the strike for the sake of all the citizens of Kalamazoo, for all business is now suffering.

The strikers then agreed to accept the first agreement provided two labor people were added to the Committee of Sanitation and Morals, in order that labor’s voice might be heard on this committee for the workers asked to have the right to submit to this committee for arbitration any grievance which might arise in the factory in the future.

Next the strikers asked to be given back their old places in the factory and to be taken back in a body or by a given date. Unfortunately for Kalamazoo, both of these propositions were refused.

The Committee of Sanitation and Morals asked the workers to be patient and trust to the fairmindedness and disinterestedness of this committee to settle such trouble as might arise in the future.

At last the strikers promised to be patient and have absolute faith in a committee made up wholly of people outside the ranks of laborers.

Then the second proposition was turned down by the corset company. They refused to take back all workers at once, but they promised to reinstate most of the strikers, saying few if any would be discriminated against. The company promised to begin reinstating the strikers at once. They promised to take back ten the first day and five or more every day thereafter until all were at work again.

This to many people looked like the beginning of an understanding on all sides. The community had been taught by the strike that it owed a duty to all its people. The factory had been thoroughly cleaned up because of the publicity given to its sanitary conditions during the strike. It will hereafter be a healthier place for everybody to work in because of the strike of these three hundred girls.

Now what was needed was some power or influence to keep the benefits which had been gained by the strike. These must be kept as a lasting good for all those who have to work for their living in Kalamazoo.

The corset workers believed that this could be attained only by the thorough organization of the workers in that factory.

For the time being, however, they were willing to live by their faith in others. They would trust the Kalamazoo Corset Co. to keep faith with its employes and the Committee of Sanitation and Morals. Now what has happened!

From the latest reports we learn that the promise to the workers has been broken.

The corset company insists on picking out the workers who are to return one by one–when they return their lives are made miserable by the people in the factory, although the company pledged its honor that no girl would be thought the worse of or treated badly for having taken part in the strike.

When the girls insisted on being taken back in groups of five or ten, they were discharged almost as soon as they sat down to work, so the strike has been renewed.

Now these splendid brave corset workers of Kalamazoo are putting these questions to all workers.

Keep in your mind, they are splendid women. They are brave women. It takes the kind of bravery that this land of ours needs to be able to tell unpopular truths to unwilling listeners because you believe the truth is good food for all people. Here are the questions they ask us: What is there left for us to do! We made a good fight and were beaten. Kalamazoo is our home.

We have given the best years of our lives to the building up of this industry.

Where are we to go!

Has anyone a right to take our work away from us and drive us from our home town, because we have been bold to cry out against injustice and evil?

We have seen the evil grow daily more deadly, living at last on the virtue of our young sisters.

Such is my story! It is a true story!

Have you caught its meaning, you of the “Listening Heart?”

Can you send word of hope and comfort to those brave girls of Kalamazoo who have dared all for a principle?

Kalamazoo is but a type of that injustice and oppression to which every working girl in our nation may be subjected. How can we help them?

Life and Labor was the monthly journal of the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). The WTUL was founded by the American Federation of Labor, which it had a contentious relationship with, in 1903. Founded to encourage women to join the A.F. of L. and for the A.F. of L. to take organizing women seriously, along with labor and workplace issues, the WTUL was also instrumental in creating whatever alliance existed between the labor and suffrage movements. Begun near the peak of the WTUL’s influence in 1911, Life and Labor’s first editor was Alice Henry (1857-1943), an Australian-born feminist, journalist, and labor activists who emigrated to the United States in 1906 and became office secretary of the Women’s Trade Union League in Chicago. She later served as the WTUL’s field organizer and director of the education. Henry’s editorship was followed by Stella M. Franklin in 1915, Amy W. Fields in in 1916, and Margaret D. Robins until the closing of the journal in 1921. While never abandoning its early strike support and union organizing, the WTUL increasingly focused on regulation of workplaces and reform of labor law. The League’s close relationship with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America makes ‘Life and Labor’ the essential publication for students of that union, as well as for those interest in labor legislation, garment workers, suffrage, early 20th century immigrant workers, women workers, and many more topics covered and advocated by ‘Life and Labor.’

PDF of issue: https://books.google.com/books/download/Life_and_Labor.pdf?id=epBZAAAAYAAJ&output=pdf