The mundane and the epoch-making. A letter from Marx in London to Engels in Manchester detailing the events and people that came together to form the International Workingmen’s Association, the First International, in 1864.

‘Karl Marx to Frederick Engels on the Founding of the First International’ (1864) from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 4 No. 67. September 25, 1924.

4th November 1864.

Dear Frederick,

Some time ago the London workers sent an address to the Paris workers with reference to Poland, calling upon them to take common action in this matter.

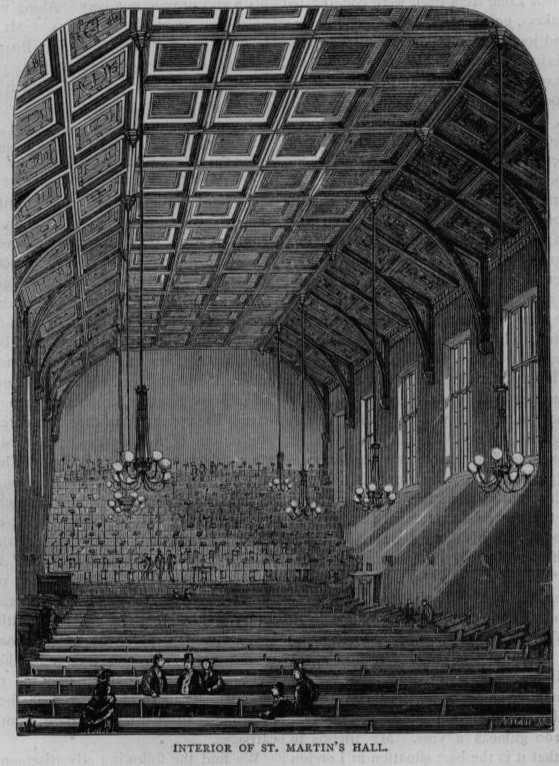

The Parisians for their part sent a deputation over here, headed by a workman called Tolain, who was actually labour candidate at the last election in Paris, and who is a very nice fellow. (His companions were very good fellows too.) A public meeting was convened in St. Martin’s Hall for 28th September by Odger (Shoemaker, chairman of the local London Trades Council the council of all London trade unions, and especially of the Suffrage Propaganda Society of the London trade unions, connected with Bright) and Cremer, a stone-mason and secretary of the stone masons trade union. (These two men brought about the great meeting of the trade unions for North America, under Bright, at the St James’ Hall, as also the Garibaldi manifestation). A certain Le Lubez was sent to me, asking I would participate on the part of the German workers’ and especially if I would send a German speaker for the meeting, etc. I sent Eccarius, who managed splendidly, whilst I assisted him as dumb figure on the platform. I knew that on this occasion real “powers” both from London and Paris would be figuring, and thus decided to depart from my otherwise fixed rule of declining all such invitations.

Le Lubez is a young Frenchman, that is, he is in the thirties, but he was brought up in Jersey and London, speaks splendid English, and is an excellent intermediary between the French and English workers. He is a music teacher, and has given French lessons as well.

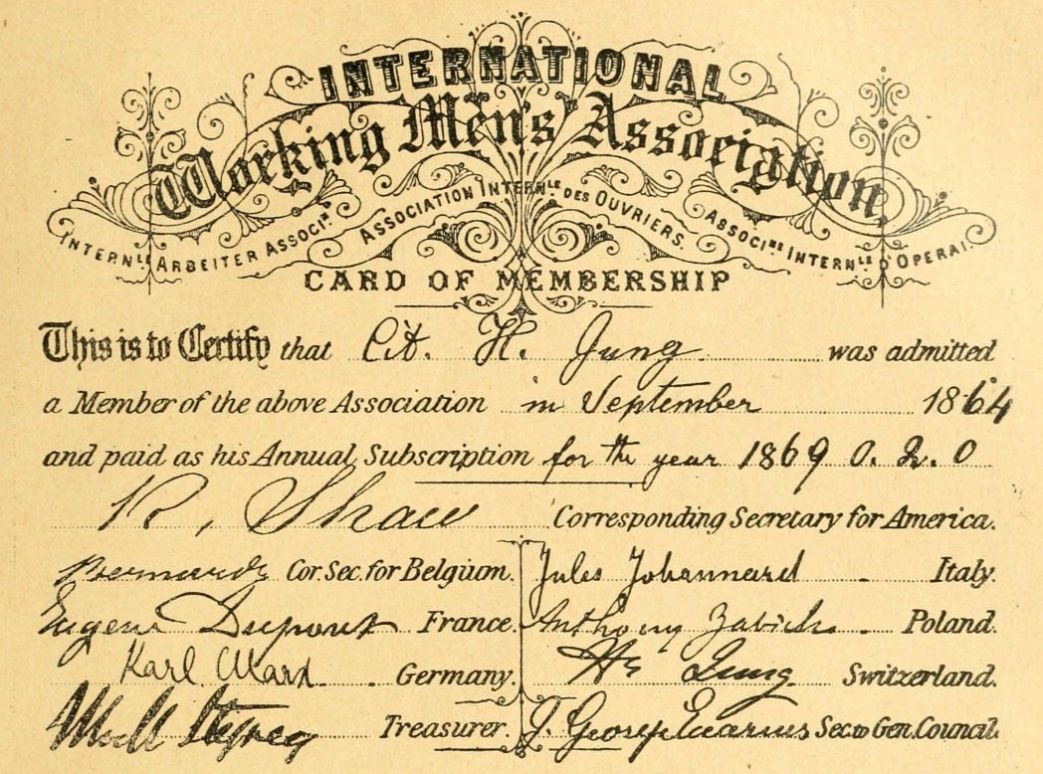

At the meeting, which was packed to suffocation (for there is obviously a revival in the working class at the present time) the London union of Italian workers was represented by Major Wolff (Thurn-Taxis, Garibaldi’s adjutant). It was resolved to found an International Labour Association, whose General Council is to have its headquarters in London, and to act as intermediary between the labour unions of Germany, Italy, France, and Eng- land. It was further resolved to convocate a general labour congress in Belgium in 1865. A provisional committee was nominated at the meeting, Odger, Cremer, and many others, in part old Chartists, old Owenites, etc., for England. Major Wolff, Fontana, and other Italians for Italy; Le Lubez, etc., for France; Eccarius and I for Germany. The committee was authorised to add as many members as it thought necessary.

So far good. I attended the first meeting of the committee. A subcommittee was nominated (including me), commissioned to draw up a declaration of principles and provisional articles. I was prevented by illness from attending the session of the subcommittee, and the session of the whole committee following this.

At these two meetings the one held by the subcommittee, followed by that of the whole committee at which I was not present, the following had occurred:

Major Wolff had submitted his statutes of the Italian Labour Unions (which possess a central organisation, but, as turned out later, consist essentially of associated auxiliary unions) to be utilised by the new association. I saw the stuff later. It was obviously a piece of Mazzini’s handiwork, so you can imagine for yourself in what spirit and in what phraseology the real question, the labour question, was dealt with. And how the nationality matters were edged in.

Besides this, a program had been drawn up by an old Owenite Weston, now himself a manufacturer, a most agreeable and well meaning man full of the utmost confusion and of unspeakable breadth.

The general committee session following this had commissioned the subcommittee to remodel Weston’s program and Wolff’s statutes. Wolff himself left for Naples, to attend the conference of the London union of Italian workers there, and to induce this union to join the London Labour Association.

The subcommittee held another meeting, at which I was again not present, as I got to know of the rendezvous too late. Here Le Lubez had submitted a declaration of principles and a revision of the Wolff statutes; these had been accepted by the subcommittee for submitting to the general committee. The general committee met on 18th October. As Eccarius had written me that danger was to be expected, I attended, and was truly horrified to hear the good Le Lubez read an introduction, in frightful phraseology, badly written, and entirely immature, claiming to be a declaration of principles. Mazzini peeped through everywhere, overlaid with the vaguest shreds of French socialism. Besides this, the Italian statutes had been almost completely accepted, although, apart from their other faults, they actually aim at something entirely impossible, a sort of central government (with Mazzini in the background of course) of the European working classes. I opposed mildly, and after much discussion Eccarius proposed that the subcommittee should once more submit the matter to a fresh “editing” contained in the Lubez declaration were however accepted.

Two days later, on 20th October, there was a meeting at my house; Cremer for the English, Fontana (Italy), and Le Lubez. (Weston was unable to come). I had not had the papers in my hands up to then (Wolff’s and Le Lubez’) and was unable to prepare anything, but was fully determined that not one line of the stuff was to be allowed to stand. In order to gain time, I suggested that we should discuss the “statutes” before beginning to “edit”. This was done. It was one o’clock in the morning before the first of 40 statutes was accepted. Cremer said (and this is what I had been aiming at): we have nothing to submit to the committee meeting on 25th October. We must postpone this meeting until 1st November. The subcommittee, on the other hand, can meet on 27th October, and try to come to a definite result. This was agreed to, and the “papers” left behind with me for me to look through.

I saw that it was impossible to make anything of the stuff. In order to justify the extremely peculiar way in which I intended to “edit” the “accepted principles”, I wrote an address to the working class (though this was not in the original plan): a sort of review of the development of the working class since 1845. On the pretext that all essentials were contained in this address, and that we must not repeat the same things three times, I altered the whole introduction, threw out the declaration of principles, and finally replaced the 40 statutes by 10. In so far as international politics are mentioned in the address, I speak of countries, not of nationalities, and denounce Russia, not the smaller states. My proposals were all accepted by the sub-committee. I was however obliged to take up two “duty” and “right” phrases, and one on “truth, morality, and justice” in the introduction to the statutes, but they are so placed that they cannot do any damage.

My address, etc. was accepted with great enthusiasm (unanimously) at the session of the general committee. The debate on the manner in which it is to be printed, etc., takes place on Tuesday. Le Lubez has received a copy for translation into French, Fontana one for translation into Italian. I myself have to translate the stuff into English.

It has been very difficult to manage the matter so that our views can appear in a form acceptable to the present standpoint of the labour movement. These same people will be holding meetings within a few weeks for suffrage, with Bright and Cobden. It will take time before the reawakened movement permits of the old boldness of speech. We must hold firmly to the cause itself, but be moderate in form. As soon as the thing is printed you shall have it.

Salut.

Yours,

K.M.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecor” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecor’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. The ECCI also published the glossy magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 monthly in German, French, Russian, and English. Unlike, Inprecor, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecor are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1924/v04n68-sep-25-1924-Inprecor-loc.pdf