A central figure in early British Communism, J.T. Murphy provides a valuable synopsis of the British Labour Party’s history.

‘The Origin and Growth of the British Labor Party’ by J.T. Murphy from Labor Defender. Vol. 2 No. 10. December, 1923.

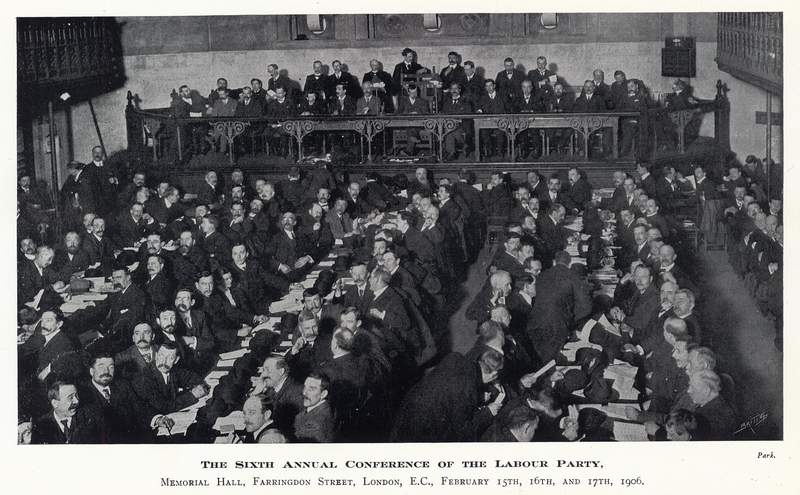

THERE exists a mistaken notion in many quarters as to the emergence of the British working class into politics and the significance of the rise of the British Labor Party. Formally, the British Labor Party came into being in the year 1906 and consequently there are those who refer to a few years preceding and tick off the date and personalities of the period, and there is the whole story.

Having seen the workers enmeshed in the snares of Liberalism, they argue the necessity of the workers passing through the school of liberalism to labor. But the formation of the British Labor Party in 1906 marks not the birth of British working class politics but their re-emergence after years of slumber.

British working class history falls into three distinct periods the revolutionary years from the beginning of last century to 1849; the years of modern trade unionism dominated by insurance and friendly society features; the re-emergence of class politics in the founding of the Labor Party.

The 18th century ends with Britain in the midst of the industrial revolution, and Europe shaken by the French Revolution which was busy breaking down the barriers of feudalism. The 19th Century begins with war in Europe, a thoroughly class conscious ruling class in Britain, nervous of the growing proletariat, a working class struggling bravely to build the first trade unions amidst the most violent persecution.

The dual forces of the industrial revolution and war, drove the village workers into the towns to be alternately swallowed in the factories or cast on the streets by unemployment A social war raged which brought to the front most of the problems which are vexing the minds of the workers today. So bitterly was the class war conducted that the question of the independence of the workers in the struggle seemed an axiom out of the range of discussion and remained so until the collapse of Chartism when totally new conditions began to prevail.

Industrial capitalism got to its feet. A period of commercial expansion opened up before British capitalism. The world market was open before her. No real competitors were ready to challenge her supremacy and the sharp characteristics of the class war which so vividly mark the earlier years of the century are almost completely removed by liberalism. Real wages advanced, conditions became easier, and amidst obvious prosperity and improvements the clarion calls to class-war action seemed vaguely distant and unreal.

This was the period when liberalism prevailed in the minds of the masses. They had no votes and even after the extension of the franchise in 1867 only a small minority could vote. The unions were securing improvements by registration and collective bargaining. It was not until severe crises accompanied by extensive unemployment and the legal onslaught on unionism, changed the whole conditions that new forces and factors arose which made imperative the demand for organized political independence on the part of the labor movement. The period of uninterferred expansion was passing. New productive forces were seeking outlets in the same market. The period of economic and political instability had begun and with it a re-awakening of the class issues which had dominated all the earlier struggles of the century. The war of 1914-18 did not sweep these issues away, but accentuated them, and drove the workers into the Labor Party, whilst the post-war period has taken matters farther still. It has not only shown the utter futility of the workers letting their politics out to Liberal or Tory parties, but has raised the question even more sharply of cleansing the Labor Party itself of the psychological policemen of the bourgeoisie.

The revolutionary epoch of the latter part of the 19th Century which finally liberated capitalism from the last vestiges of feudalism were the years wherein the proletariat learned its first lesson of organization and class war. The intervening years between then and now were the years of gestation wherein the workers without political vision, builded greater than they knew. Now, in the new epoch of revolution, the British Labor Movement is in ferment, questioning not the advisability of the formation of a Labor Party but its clarity of vision in the interests of the workers and its freedom from capitalistic control.

The origin and development of the British Labor Party, therefore, lies deep in the history of the working class struggle. It is not the beginning of independent working class action, but a part of a process whereby the workers hammer out their instruments of struggle and final victory as the following narrative, I hope, will make clear.

Class War Politics

The working class movement of Britain was born in the midst of a revolution of which it was not the leader but the product. The history of the industrial revolution 1762 to 1830 is more than the record of industrial expansion and development; it tells of the production of a vast army of workers desperately in need of a fraction of the wealth they were creating, who had had no experience of organized struggle but were compelled to organize or perish; of a ruling class which was being reinforced by a rising industrial and commercial class and yet which maintained a conservative class-conscious rulership which would not concede anything without a fight. The Hammonds have vividly described in “The Town Labourer,” “The Village Labourer” and “the Skilled Labourer” the arrogant superiority of the governing class and the enormous difficulties the workers had to overcome. They say:

“The classes that possessed authority in the State and the classes that had acquired the new wealth, landlords, churchmen, judges, manufacturers, one and all, understood by the government, the protection of society from the fate that had overtaken the privileged classes in France poor man is esteemed only as an instrument of wealth.”

With all power in the hands of an oligarchy there was no question before the workers as to how to use a vote or select a representative in parliamentary democracy. To make their presence felt at all they were driven to political demonstrations, strikes, appeals for modification of the law or the application of old ones. The whole period from 1756 up to the first twenty years of the 19th century is characterized by these methods. Trades Unionists were punished as rebels and revolutionists guilty of sedition. But persecution did not stop the process and the process was producing the large new class of commercialists who were anxious to play a more important role in the formulation of the politics of the country. From these ranks such men as Francis Place lined up with the workers and played an important part in the political campaign for the legalizing of Trade Unions.

Within the first forty years of the 19th century there is hardly a phase of class warfare that is not brought into the foreground of political activity. Petitions and demonstrations, machine smashing and sabotage, demands for armed re- volt, one big union of the workers, adult suffrage, a Parliament of workers, the Co-operative Commonwealth, the abolition of Parliament, sudden social revolution, all came to the front. Out of the turmoil came the first definite political organization in the form of the National Union of the Working Classes, under the leadership of William Lovett, demanding manhood suffrage. This organization was involved in much of the reform agitation which culminated in the political changes of 1832, and then passed away.

The innovation of Owenism needs only to be mentioned to remind us of the magnitude of the political ferment and the class character of the agitation. The failure of the grandiose schemes both of Co-operation and unionism and the disillusionment following the victory of the middle class in 1832, paved the way to the growth of Chartism. From 1837 to 1844 is the hey-day of this movement which constitutes the next great organized political activity of the British working class. From end to end of the Kingdom the organization grew in volume and power. Lovett was the author of the Charter and remarkable leader assisted by many able men–Brontierre, O’Brien, Stephens, Harvey, and a host of others, though not all of these were well received by the workers. The class consciousness manifested it- self in the refusal of the workers to have any leader who did not belong to the working class. It was this fact which strengthened the position of Lovett and enabled him to launch the London Workingmen’s Association in 1836 which became a powerful factor in the Chartsist movement. The Charter demanded Universal Suffrage, the Ballot, Annual Parliaments, Payment of Members and Abolition of Property Qualifications.

These demands reveal at once both the reason of the association with liberalism and the lack of independent labor representation. In 1836 there were 6,023.752 males over 21 years of age and only 840,000 had votes and owing to the unequal state of representation about one-fifth of that number had the power of returning a majority of members. That is a “little” different from the political situation in America and Britain today, whilst the non-payment of members coupled with the property qualification made independent working class representation almost impossible. The obvious tactic was to use liberalism in the Parliament as an ally until it became possible to assert independent labor representation. This explains much of the influence of liberalism in the labor movement, and why even when the unions took up the question of Parliamentary representation and provided funds the first labor men were nearer to liberalism than to class-war politics.

Elementary as the Chartist program undoubtedly was, it guided the great political activity fermented by the terrible conditions which prevailed throughout this period. But with the lack of political experience, the immaturity of social science and the consequent lack of theoretically equipped leaders, with often bad leadership, impatience and want of education among the masses, it was utterly impossible to consolidate the movement and give it a political goal with the pathway to it clearly defined.

The beginning of a new period of economic expansion on the part of British capitalism swept the groundwork away from Utopias, violent upheavals, and mass agitation, and left the workers to assimilate their experiences in a period of thriving liberalism.

The Coming of the Labor Parties

From the fifties up to 1875 the industrial expansion of England is phenomenal. She became the workshop of the world, and the workers were able to benefit from this expansion. The main body of workers became absorbed in the development of the trade unions and the Co-operatives. In so far as either movement had any political consciousness they renounced class warfare and conceived the idea of their organizations as a permanent part of what appeared to them a permanent social order. Although the First International Workingmen’s Association, formed in 1864, held aloft the banner of class war for a few years and undoubtedly influenced the trade unions which were attached to it, the political ideas within these organizations and of the workers in general reflected the doctrines of liberalism.

The immediate tasks which the workers could accomplish were well within the limits of liberal capitalism and only the exceptional political student could see beyond these limits. Liberalism reluctantly accepted the existence of the unions and so long as the conditions which obtained did not compel the workers to use the unions as instruments to challenge the fundamentals of the system, adaption and compromise were the keys to the development of society and the pacification of the workers. No wonder Gladstone was triumphant.

Nevertheless, the development of the unions even under the domination of this philosophy brought them, time and again, face to face with situations which demanded common political and industrial action. From as far back as 1825, joint committees of the unions were formed to combat the combination laws, again in 1834 to protest against the punishment of the Dorchester laborers, again in 1838 to conduct the case of the Trade Unions before a Parliamentary Committee. These were transient, but by 1860 permanent Trade Councils were established in Glasgow, Sheffield, Liverpool and Edinburgh, and London in 1861. The latter became the most important and for a number of years was dominated by the Junta (a group of able leaders among whom were George Odger, Howell, William Allen of the Engineers, Applegarth of the Carpenters). The Councils arouse out of strikes but became the instrument for participating in general politics.

In 1862 the London Council joined in the agitation in support of the Northern States against Negro Slavery. In 1866 it joined in the agitation of the Franchise Reform Bill and co-operated with the International Working Men’s Association in the demand for Democratic Reform from all European Governments. The London Council joined with Alexander McDonald and Alexander Campbell of the Coal Miners, in bringing the Glasgow Trades Council into a campaign. for the amendment of the Masters’ and Servants’ Acts. This campaign led to the first National. Conference of Trade Unions in 1864 and through it to big agitations which succeeded by 1867 in securing amendments to the Act. In this campaign they used John Bright but the question of the independence of the movement as a workers’ movement was never in question. It was such questions as the Masters and Servants’ Act, the legalizing of the unions, collective responsibility of unions for disputes, rights of pickets, etc., which sharpened the issue of political action.

With the passing of the 1867 Franchise Reform Bill the movement for independent Labor Representation received an impetus. The Trades Councils urged the small proportion of Trade Unionists to register. Next, to vote for candidates who would support Trade Union demands. By 1868 Trades Union Congress had been established and in 1871 a Parliamentary Committee was set up. The unions began to run independent labor candidates. George Odger was a candidate in the elections of 1869 and ’70. In 1874 the Miners, Ironworkers and a few others voted money for parliamentary candidates. At the next general election 13 labor candidates were run against Liberal and Tory candidates. “At Stafford and Morpeth the Liberals accepted what they were powerless to prevent,” says Mr. S. Webb, and Alexander Macdonald and Thomas Burt of the National Union of Miners became the first Labor members of the House of Commons.

The path of an Independent Labor Party was this one opening up out of the struggle of the Unions. Whatever may be said about the political conceptions of the first Labor men, in the actual struggle they stood against the liberals and tories of the day.

The extension of the franchise had come by pressure from the unions and the rising middle class. Immediately this victory was won, although the Reform Bill of 1868 gave the vote to only a small minority, it gave the chance, immediately seized to establish independent labor representation. The question of support for liberals at any time only arose where there was no chance of independent labor representation.

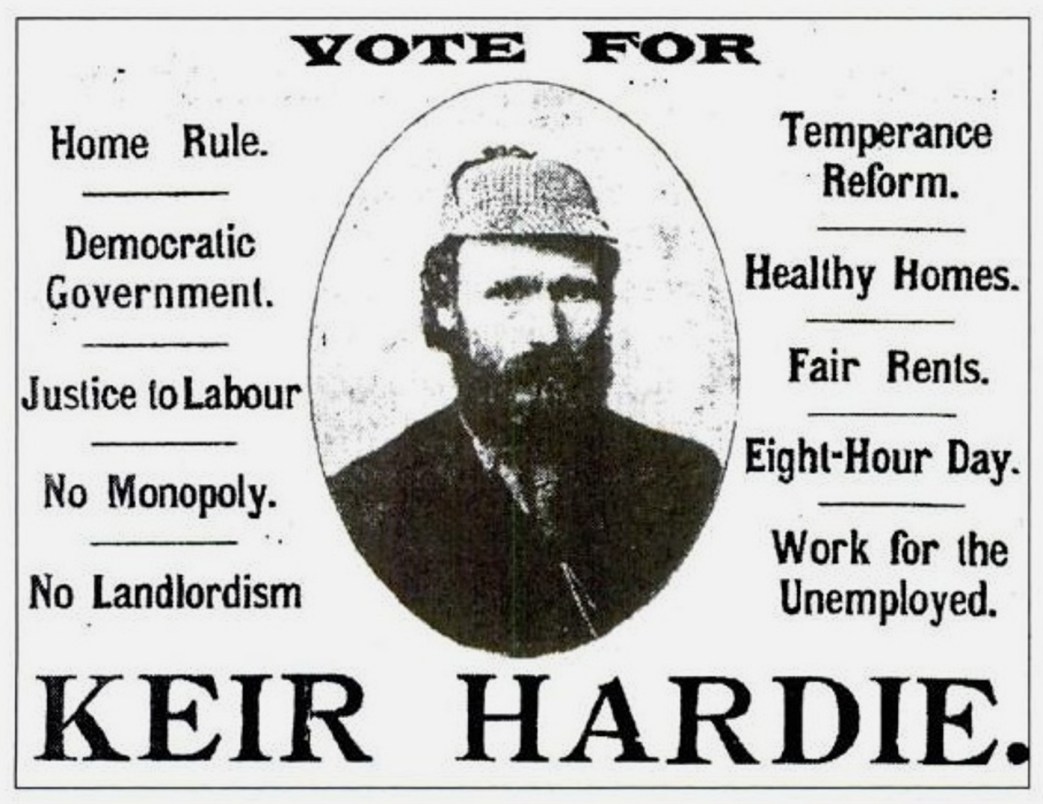

By 1880, this process is accentuated by the economic crises of the period. New political parties arose catching up again the threads of the politics of the Chartist movement and Socialism. The Social Democratic Federation founded by H.M. Hyndman propagated the Marxian doctrines of the class war, while the Fabian Society led by Mr. Webb, began to try its hand with Socialism in practical politics. The Independent Labor Party, under the leadership of Keir Hardie, took up the cudgels for Socialism. All of these became important factors in the working class movement struggling for clarity of political purpose and warring against liberal thought in the ranks of the workers. The dual process of the struggle of the unions against legal limitations, and the Socialist agitation thriving on the recurring social crises, brought to a head the question of uniting all the working class forces into a federated labor party.

The Trade Union Congress of 1899 brought matters to a decision after all the numerous efforts to secure a Labor Party. James Holmes of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, drafted the following resolution:

“This Congress having regard to the decisions of former years, and with a view to securing a better representation of the interests of Labor in the House of Commons, hereby instructs the Parliamentary Committee of the Trade Union Congress to invite the co- operation of all the Co-operative, Socialist, Trade Union and other working class organizations jointly to co-operate in lines mutually agreed upon in convening a special congress of representatives from such of the above mentioned organizations as may be willing to take part to devise ways and means for securing of an increased number of Labor members to the next Parliament.”

James Sexton of the Dockers, seconded. 546,000 voted for, 400,000 voted against.

A committee consisting of four of the Parliamentary Committee was set up. This included Words (Liberal), W.C. Steadman (Fabian),Will Thorne (S.D.F.), A. Bell, Keir Hardie, J. Ramsay McDonald, Harry Quelch, H.R. Taylor, S. B. Show and E. R. Pease. On February 27th and 28th, 1900, sixty-three years after the London Working Men’s Union had formulated the People’s Charter, 120 delegates met in London and established the Labor Representation Committee with McDonald as Secretary. By 1906 the Committee was transformed into the Labor Party. But in the interval the vexed question of liberalism was settled. Richard Bell who was on the first Representation Committee, sent his “good wishes” to the Liberal Candidate against G.H. Roberts, the I.L.P. Candidate. The latter had the reputation at that time as a fiery Socialist and internationalist. But Arthur Henderson and David Shackleton who were very moderate labor men, supported him.

The action of Bell created a ferment and the matter was settled by the Newcastle Conference 1903, when it was agreed that “members of the E.C. and officials of affiliated organizations should strictly abstain from identifying themselves with or promoting the interests of any section of the liberal or conservative parties…

The victories in 1906 general election established the Labor Party and the work of Kier Hardie, whom we can regard as the outstanding figure of the modern movement to establish the Labor Party, was thus on the way to success. He had been assisted ably by McDonald, Sexton Quelch, Bruce Glacier, J.R. Clynes, Pete Curran, Tillett, Smille, Henderson and Snowden. Whatever the political differences of the parties they were intent on thrashing the differences out within the framework of the Federal Party. All the party organs plus the unions, plus the efforts of such as Blatchford, who at that time created a remarkable impression by his writings, joined in the campaign for the independent party of the workers. Blatchford probably put the case simplest of all. He asked, “Do you elect your employers as officials of your Trade Unions? Do you send employers as delegates to your Trade Union Congress? You would laugh at the suggestion.

“If an employer’s interests are opposed to your interests in business, what reason have you for supposing that his interests and yours are not opposed in politics? If you oppose a man as an employer, why do you vote for him as a member of Parliament? During a strike there are no Tories and Liberals amongst the strikers; they are all workers. The issue is not between Liberals and Tories; it is an issue between the privileged classes and the workers.”

It was this kind of argument plus the experiences of the Unions which brought the Labor Party to the front and made it possible to unite the varying working class organizations upon specific programs of action. A constitution was framed broad enough to permit the various parties to be a part of common organization without infringing their programs which they sought to get adopted by their colleagues of the working class movement. The Socialists struggled vigorously against the liberalism within the party but remained in the Labor Party. In recent years

the Socialists who took the lead from the “lib-lab” elements are battling against the Communists. In this they are losing ground for the conviction is growing in the ranks of the labor movement that differences in political policies should be fought out within the ranks of the workers, that only by presenting a united front against the common enemy is it possible for the workers to achieve victory.

The Labor Herald was the monthly publication of the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), in immensely important link between the IWW of the 1910s and the CIO of the 1930s. It was begun by veteran labor organizer and Communist leader William Z. Foster in 1920 as an attempt to unite militants within various unions while continuing the industrial unionism tradition of the IWW, though it was opposed to “dual unionism” and favored the formation of a Labor Party. Although it would become financially supported by the Communist International and Communist Party of America, it remained autonomous, was a network and not a membership organization, and included many radicals outside the Communist Party. In 1924 Labor Herald was folded into Workers Monthly, an explicitly Party organ and in 1927 ‘Labor Unity’ became the organ of a now CP dominated TUEL. In 1929 and the turn towards Red Unions in the Third Period, TUEL was wound up and replaced by the Trade Union Unity League, a section of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profitern) and continued to publish Labor Unity until 1935. Labor Herald remains an important labor-orientated journal by revolutionaries in US left history and would be referenced by activists, along with TUEL, along after it’s heyday.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborherald/v2n10-dec-1923.pdf