During the first wave of Southern textile worker organizing in 1929 occurred a number of deadly assaults on organizers and strikers. One of the most violent was the murder of six (one dying of wounds after this article) striking mill workers, the wounding and arrest of many others, on October 2 in Marion, North Carolina by sheriffs deputies in service of the mill owners.

‘Five Pounds of Lead and Five Martyrs: The Marion Massacre’ by Liston M. Oak from Labor Defender. Vol. 4 No. 11. November, 1929.

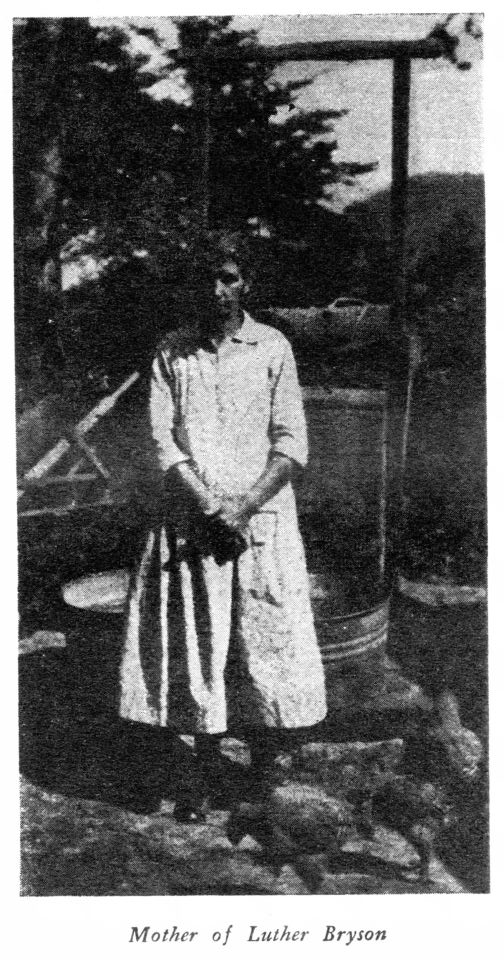

“IT just seems like he was too young to die,” sobbed the care-worn old mother of Luther Bryson.

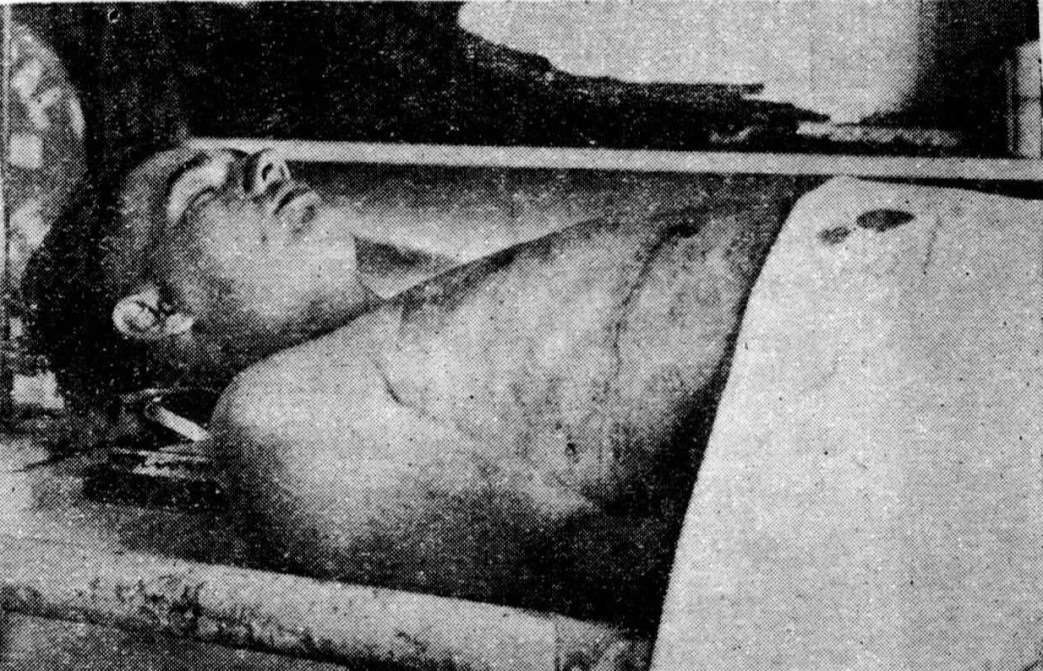

Her emaciated body bowed by long years of toil on farm and in mill was shaken with grief. All night she had stood in the hospital, waiting. Finally, the casual professional nurses admitted her to the bedside of her dying son. He was sinking into the final coma as the day broke. All night Luther, the fourth of the wounded strikers at Marion to die, had battled against death that he might live to battle again against the bosses.

Three others Randolph Hall, Sam had already Vickers and George Jonas died and James Roberts died later. Five more martyrs in the class war of the new South five martyrs who, like Ella May, gave their lives in the fight of the southern mill workers against the stretch-out system, against starvation wages and all the other iniquities of capitalist rationalization, exploitation and oppression. Twenty others were wounded, of whom two more may die. Others will be crippled for life.

“Damn good marksmanship, I say, boasted S. W. Baldwin, president of the Marion Manufacturing Company mill at the gates of which the strikers were slaughtered. “There were three tons of lead used for every enemy soldier killed in the world war, while Wednesday morning only five pounds of lead were shot and five were killed and twenty wounded. If I ever organize an army I’ll give those deputies a job. They are damn good shots.”

This boast was made to a group of newspaper reporters, who didn’t dare quote him. Next day Baldwin was in court to sign bonds for the deputies, and the superintendents, foremen and stool pigeons of his mill who were arrested, charged with murder.

When Fred Beal, Louis McLaughlin and seventy other strikers were arrested in Gastonia charged with the murder of Chief of Police Aderholt, sixteen of them were held without bond in jail for four months.

Then nine of them were released and the charges against them nolle prossed. The other seven are still on trial as this is written. But when deputy sheriffs are charged with the murder of five Marion strikers they are released immediately on $2,000 bond signed by their lord and master, the president of the mill. Then almost fifty strikers are arrested charged with rebellion against the state and resisting an officer! Impartial justice!

At the preliminary investigation under Judge Harding, sent in by the mill-owning Governor of North Carolina to whitewash the authorities, it was shown that nearly all of the strikers were shot in the back as they were fleeing from the fusillade of bullets from the forces of “law and order.” The night shift had walked out on a spontaneous strike, a strike against the violations of the sell-out agreement reached by the mill owners and the United Textile Workers officials, with the Governor’s representative acting as “impartial” chairman. The United Textile Workers’ bureaucrats had nothing to do with this spontaneous strike—they don’t approve of it at all. The militant mill workers them- selves, too militant to suit the misleaders sent to restore “industrial peace,” rebelled and walked out. With only their own local leaders, they formed a picket line and from one o’clock to six-thirty, they walked quietly up and down the road in front of the mill gate.

At six-thirty the day shift came. Most of them joined the picket line, but a few scabs wanted to go in to work.

“Open up that line,” yelled Sheriff Adkins. “Let them men in here.”

“To hell with the bosses and their scabs,” someone shouted.

The guardian of law and order, sworn to protect the rights of property and the sacred right of slaves to “work where and when they please without dictation from a union,” as the capitalist press put it next day, saw his duty clearly, and he did it in efficient fashion. First he and his deputies let loose the tear gas bombs, blinding the strikers. Then they opened fire, seventy shots with deadly aim at the blinded fleeing and unarmed strikers. The sheriff himself ran up to “old man” Jonas, militant fighter throughout the previous strike, grabbed him with his left hand, shoved his pistol in Jonas’ stomach, and fired. Jonas was one of the two or three not hit in the back by the assassins’ bullets. He dropped in his tracks. One of his fellow workers rushed up to rescue him and was stopped by another bullet. He crawled into the ditch to die.

It was all over in two minutes. Twenty-five strikers lay wounded on the road. They had been caught in a trap. On one side of the road is the mill fence. On the other is a high cement wall. Nowhere to run to cover except down the road under the fire of the deputies lined up along the mill fence. The strikers in back were easy targets for the murderous thugs deputized to slaughter them.

In the afternoon the mill company ordered a road drag to scrape the road and cover up the pools of dried blood left by twenty-five wounded strikers. Although with only one-third of its force, the mill’s spindles and looms kept turning out fabric. Workers’ lives may be snuffed out but profits must not stop.

The mass funeral came on Friday. On the slopes of a hill, under the limbs of trees, the caskets were laid out. Fifteen hundred workers gathered around the bodies of their martyred fellow workers, in front of the speaking stand. Fifteen hundred mill slaves in revolt against the starvation wages that left them worn-out at the age of thirty or forty.

For this gathering of workers newly awakened to the meaning of the class struggle, of unionism, the United Textile Workers’ Union had nothing to offer but a long flow of sentimental religious oratory.

Five preachers, three local fundamentalists and two, James Myers of the Federal Council of Churches and the Rev. A.J. Muste of Brookwood, “liberal modernists.” The burden of their sermons was that the hope of salvation both from hell in this world and the next lies in the church, in forgiveness of their enemies, in love, in the brotherhood of man. “The devil has got into the hearts of the mill owners.”

Muste, praising Governor Gardner, called upon the State of North Carolina to “wipe out this stain upon its honor by improving conditions in the mills.”

L.L. Jenkins, Asheville banker who owns half of Buncombe County spoke. He negotiated the sell-out agreement that ended a two months’ strike, surrendering everything the workers were striking for, at a moment when they believed the strike was won. “My friends,” he said in a tremulous voice, “I owe everything I have to you, my people. You have stood faithfully by the loom and the spindle in my mill and produced my wealth. I have appeared before you and asked your suffrage to elevate me to high positions of honor in the State. Now I will reward you in your hour of need. I am glad to see the spirit of Jesus here today. Only the Christian spirit can solve our labor problems. I have told my associates who own mills in Gastonia that they must cooperate with me and the United Textile Workers to combat Communism and atheism. God bless you.”

The southern textile workers are in revolt. When they strike, they are militant, even despite reactionary leadership. The local leaders had the Marion mill over half organized before they called upon the U.T.W. for help. Asked why they called upon the U.T.W. instead of the National Textile Workers’ Union they answered, “Well, we had heard of the U.T.W. but the other union is new and we had never heard of it until this year and thought we’d better get the old union in here.” Before this they knew nothing of the treachery of the U.T.W. bureaucrats. They did not know as thousands of southern workers in textile centers like Gastonia knew, that the class collaboration industrial peace, efficiency scheme policies of the U.T.W. bureaucrats are policies of betrayal and desertion.

Many of the Marion workers are still not disillusioned with the U.T.W. But they do know that the state is not impartial. They know that wherever and whenever workers are engaged in a militant fight for better conditions the police shoot them down, in Marion as at Gastonia.

The mill barons and their organs such as the Gastonia Gazette and the Charlotte News and the Observer, have blamed all the violence in the South upon the Communists. The murder of Ella May was blamed on the Communists. “The mill owners are contented and if the Communists would leave all would be well,” they said.

But the murder of five Marion strikers cannot be blamed upon Communists. It proves that the issue in the class struggle in the new industrialized South is unionism, the right of workers to organize, strike, picket, and defend themselves against murderous attacks. It proves the militancy of the southern mill workers even where the U.T.W. has tried to quell their rebellion. The leader of these militant southern mill workers in their struggles that are surely increasing in number and size with ever-sharpening class lines and issues, will be the National Textile Workers’ Union.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Not only were these among the most successful campaigns by Communists, they were among the most important of the period and the urgency and activity is duly reflected in its pages. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1929/v04n11-nov-1929-LD.pdf