Still true. The formation of the Japanese-Mexican Labor Association and 1903 strike in the sugar beet fields of Southern California was a historic moment in the U.S. and international workers’ movement.

‘Internationalism is Our Only Hope’ from The Worker (New York). Vol. 13 No. 1. April 5, 1903.

Workingmen of Southern California Learning that Mexican and Japanese Laborers May Become Loyal Brothers Instead of Enemies.

LOS ANGELES, Cal., March 20.One of the greatest difficulties with which the workingmen of Southern California have had to contend is the systematic flooding of the country with more workers than can get employment, so as to keep up keen competition for jobs and paralyze the efforts of the working class to protect itself by organization. The Southern Pacific Railway Company, which directly or indirectly dominates almost all industry in this part of the country, is the great sinner in this respect. By procuring the publication in Eastern papers and magazines, not of advertisements–oh, no–of well written and richly illustrated articles setting forth the delights of life in Southern California, the good wages and ease of getting employment, the certainty of any Industrious workingman soon becoming independently wealthy here, they induce Eastern mechanics and artizans to spend their little savings and mortgage their future in order to get here, only to find themselves stranded, out of a job for months at a time, and forced to beg for permission to work at miserably low wages.

To supply a surplus of unskilled labor for the railroads, agriculture, and other industries Mexicans and Japanese are enticed here by similar methods. They come in under contract and in debt to the contractors, and are carefully kept in debt and if they complain are turned off to starve, scab, beg, or steal, as best they may.

On account of the difference of language, customs, and standard of liv Ing. It has heretofore been almost impossible for the American workmen to get into touch with these imported laborers, and bitter hatred has been the feeling generally entertained in regard to them.

Of late, however, the situation begins to change a little. A start has been made in organizing the Mexican laborers here and it is hoped they will soon develop the idea of united action for their own defense and work in harmony with the American organizations for the common good. The success of the United Mine Workers in the East in organizing the Italians, Hungarians, and Slavs who were imported as strike-breakers and the fact that these have become staunch unionists gives us hope of similar success here.

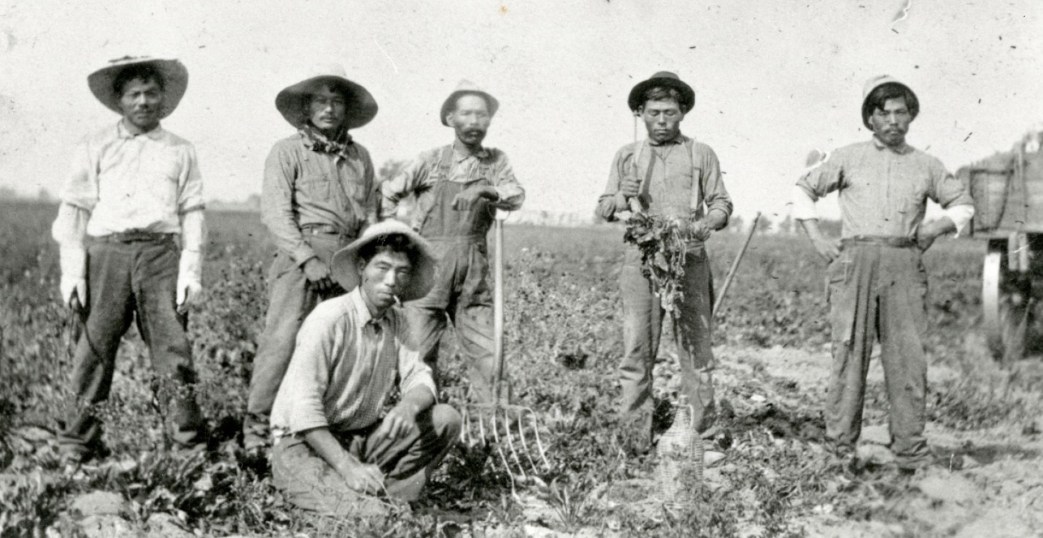

Further reason for hope is given by the strike of some three hundred Mexicans and seven hundred Japanese employed–or, rather, enslaved–in the beet-sugar industry at Oxnard, who are making a brave and sturdy fight against the extreme conditions of overwork and underpay and eternal indebtedness to the contractor.

Internationalism is the word for the workers. So long as we allow ourselves to be divided by national or racial prejudice, so long the workers of each race can be played off against those of another, to the detriment of both and the great profit of the boss. As we learn to understand and trust and be loyal to our fellow toilers whatever their language or religion, we multiply our strength and begin to deserve success.

The Worker, and its predecessor The People, emerged from the 1899 split in the Socialist Labor Party of America led by Henry Slobodin and Morris Hillquit, who published their own edition of the SLP’s paper in Springfield, Massachusetts. Their ‘The People’ had the same banner, format, and numbering as their rival De Leon’s. The new group emerged as the Social Democratic Party and with a Chicago group of the same name these two Social Democratic Parties would become the Socialist Party of America at a 1901 conference. That same year the paper’s name was changed from The People to The Worker with publishing moved to New York City. The Worker continued as a weekly until December 1908 when it was folded into the socialist daily, The New York Call.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-the-worker/030405-worker-v13n01.pdf