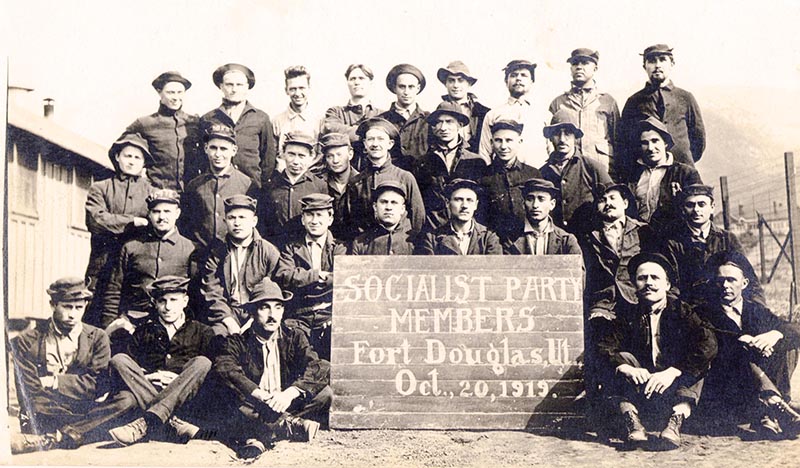

Louis Fraina, reflecting on his recent stay in jail, writes on the treatment of the political prisoner in the United States and the centrality of the fight to free our captured comrades.

‘The Crime of Crimes’ by Louis C. Fraina from Class Struggle. Vol. 3 No. 1. February, 1919.

I was in the detention “coop” waiting for bail after being arrested for agitation against conscription. In the room were a number of other criminals, their appearance a mixture of dejection, swagger and trembling apprehension. Two men — one was only a boy — had been convicted of selling cocaine the boy was himself a victim, and was in a terrible state, not because of being deprived of his liberty as such, but because that meant being deprived of his opportunity to use cocaine — unless he could secure it surreptitiously in prison. Another had been convicted of selling liquor to soldiers; still another for the crime of burglary…An Assistant District Attorney had come in, and a friend of my co-criminal, Ralph Cheney, tried to make him see our crime in its true light as a political offense. But the D.A. wouldn’t; he told us: “I sympathize with these other men here, they are ignorant and the victims of circumstances; but you — your crime is unforgiveable, since it is a conscious and willful assault upon law and order.”…

The crime of crimes is an assault upon the prevailing ideology, upon the prevailing social order, upon the supremacy of Capitalism. Ordinary crimes are considered normal, natural; they are not a menace to the prevailing system: on the contrary, they are a necessary phase of this system, a means for its preservation. The criminal against law and order is the ally of the criminal of law and order — a holy alliance characteristic of a society based on class divisions. But the political criminal is dangerous; and the loftier his purposes are, the greater becomes his danger to Capitalism.

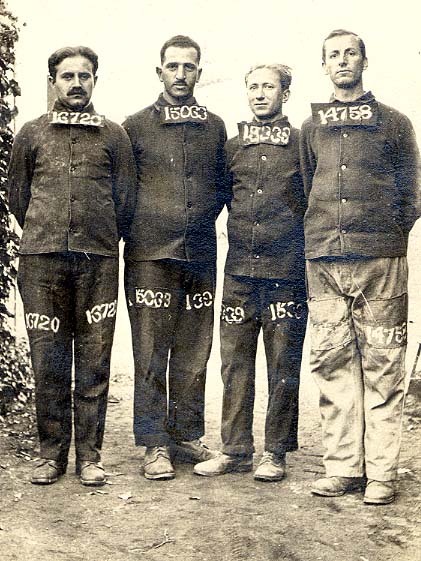

It is natural, accordingly, that the political criminal should find no sympathy among the defenders of law and order. The ordinary criminal, naturally, is treated brutally, since brutality is inherent in the beast of Capital; but the political criminal is treated even more brutally, with a conscious and purposeful brutality — the brutality of the slave owner toward slaves in revolt. This is emphasized all the more, as the American Government recognizes no such thing as political crimes — a tactical necessity to prevent the development of class consciousness. The political criminal must endure all the ignominy of the ordinary criminal, plus. This refusal to recognize political crimes is a consequence of the illusions of democracy and strengthens these illusions.

Perhaps no belligerent government has been as savage toward its political criminals as has the American Government — a fact blisteringly characterizing our democracy. All the evidence indicates that the Conscientious Objectors in this country have had infinitely more suffering and ignominy inflicted upon them than the Conscientious Objectors in England. Karl Liebknecht and William Dittmann urge the people in Berlin to open revolt, and are given sentences of four and a half and three and a half years; in New York City, four Russian men are given twenty years each, and one Russian girl fifteen years in prison, for issuing a leaflet declaring that President Wilson was a hypocrite in his policy on Russia. Fritz Adler in Austria assassinates Premier Sturgkh, and is given thirteen years in prison; Eugene V. Debs makes a speech, and is sentenced to ten years. Our political criminals are treated miserably, denied opportunity for free communication with their comrades; a revolutionary Socialist in Italy is convicted of treason, receives four years in prison, and while in prison edits the Socialist daily newspaper, L’Avanti!

All this is a consequence of the vicious and unparalleled repressive character of the Espionage Laws. Nowhere, not even in Germany, were the laws against freedom of expression as severe as in our Espionage Acts. These measures were passed to punish enemy espionage; but instead of being used against the enemy, they were most frequently and severely used against the Socialist and the radical. Is Germany or Socialism the real enemy of Capitalism and Imperialism? The crime of crimes was not espionage, but awakening the consciousness of the masses; and the Department of Justice acted accordingly.

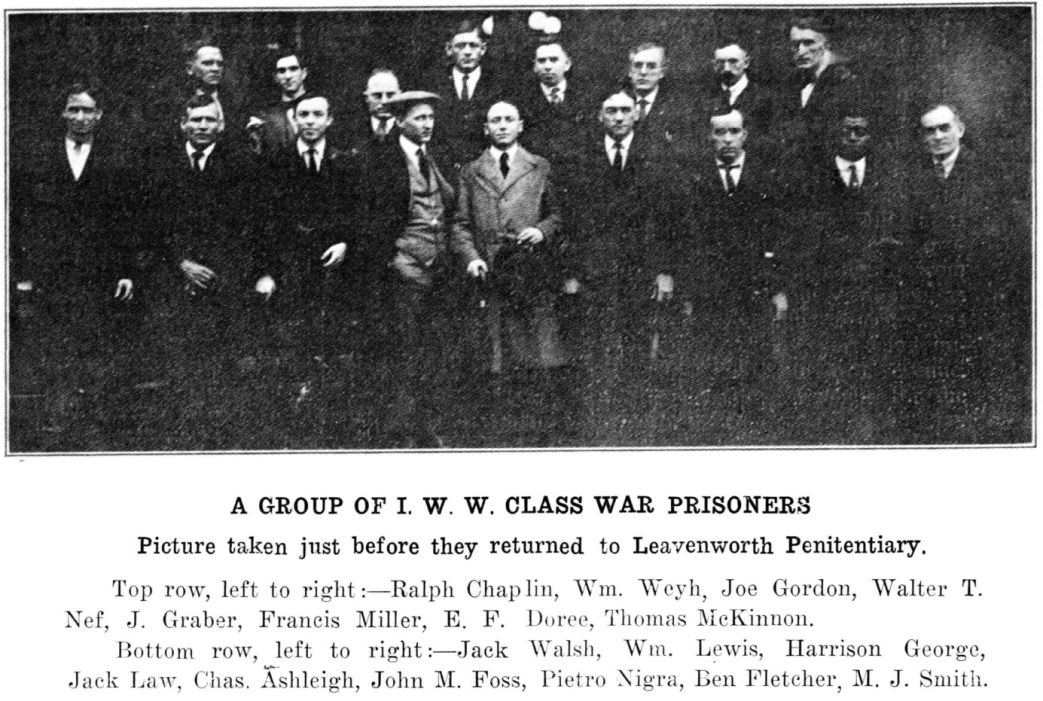

The class character of political crimes is still more apparent in the cases of industrial agitation. The I.W.W. trial, with its savage verdict, clearly indicates that the assault upon the industrial supremacy of Capitalism is considered more dangerous than the assault upon morals. All the testimony proved that the I.W.W. defendants had been engaged in industrial agitation, in organizing strikes for better conditions, in trying to use the conditions of the war precisely as they used the conditions of peace — to organize the struggle against Capitalism. Men and women in Italy are arrested for insurrectionary fighting in the streets of Milan and other cities, and are not punished as severely as these I.W.W.’s for organizing strikes to secure better conditions.

And all this savage repression, all this repudiation of democracy, proceeded simultaneously with the representatives of American Capitalism speaking of democracy in the loftiest strains of eloquence and poetry. A good part of the world was hypnotized — the United States are the great exemplars of democracy! And they are, since this democracy means bourgeois democracy, which is the authority of one class over another, the instrument for the repression of the proletariat. The more Capitalism develops, the more necessary becomes a deceptive development of the reforms and words of democracy, that cloak the sinister interests of reaction.

Reparation is being demanded of Germany for its crimes against the world: the Socialist proletariat demands reparation of the real criminal — international Imperialism. The Socialist proletariat, moreover, demands reparation for the political criminals imprisoned or about to be imprisoned for their struggle to make America safe for democracy. The problem of the political criminals is an important one, since it means a hampering of the aggressive proletarian movement if our active and militant comrades are to be imprisoned and kept in prison. Socialism must adopt new forms of struggle, new means of agitation, as reaction conquers…

Immediately upon the conclusion of the armistice, there developed a movement to secure amnesty for political prisoners; there was even a rumor that amnesty would be granted political criminals by the President on New Year’s day. But Woodrow Wilson is apparently too occupied with making Europe safe for democracy to devote any time to democracy in our own country. And, while political amnesty was being agitated, it developed that the American Government had determined upon the policy of deporting every single agitator who was born in a foreign country, regardless of whether a citizen or how long he had been in this country, if this agitator was convicted of a political crime. This is a serious issue. The policy of deportation would enormously weaken our movement — it is the most important issue in our campaign for political prisoners.

The problem of political criminals is part and parcel of the general problems of the proletarian movement. Political amnesty must be secured, not by grace of the master class, but through the militant action of the proletarian movement. If, in Europe, political criminals are not dealt with as savagely as in this country, it is because the proletariat and Socialism are more conscious and aggressive — more revolutionary.

The issue must be made a working class issue, it must be used to develop the class action of the proletariat. The struggle in the courts is necessary, but not enough; the propaganda must be one of developing the industrial action of the working class, of using the industrial might of the workers to secure our demands. In this sense, the struggle for our imprisoned comrades becomes one phase of the larger struggle — the struggle for the Social Revolution.

Open the prison gates! On to Socialism!

The Class Struggle is considered among the first pro-Bolshevik journal in the United States and began in the aftermath of Russia’s February Revolution. A bi-monthly published between May 1917 and November 1919 in New York City by the Socialist Publication Society, its original editors were Ludwig Lore, Louis B. Boudin, and Louis C. Fraina. The Class Struggle became the primary English-language theoretical periodical of the Socialist Party’s left wing and emerging Communist movement. Its last issue was published by the Communist Labor Party of America.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/class-struggle/v3n1feb1919.pdf