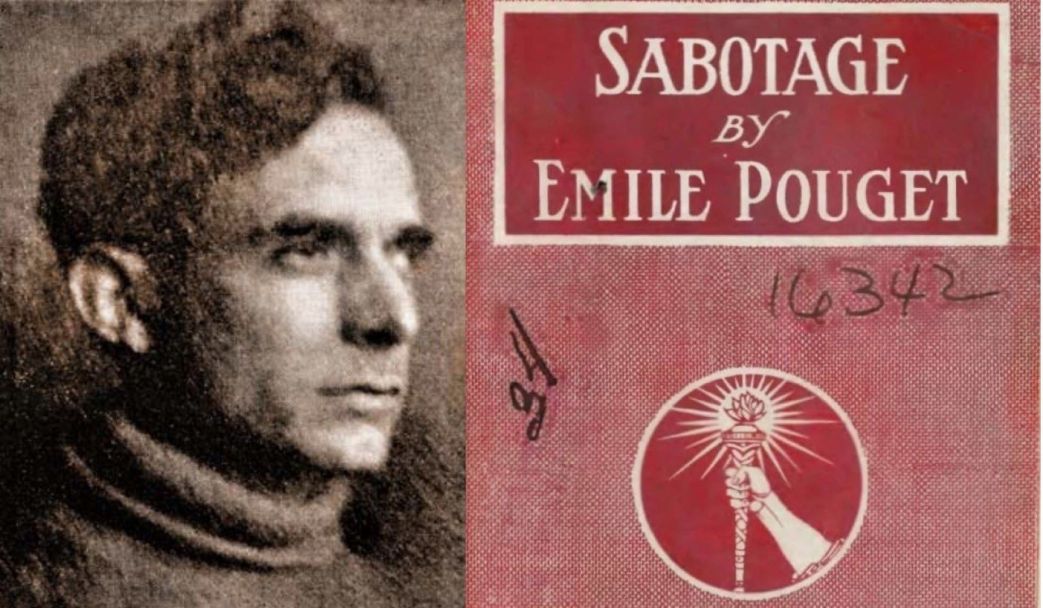

When it first arrived in the U.S., introduced by Arturo Giovannitti, Emile Pouget’s ‘Sabotage’ was the topic of much discussion and debate. Louis Fraina’s review

‘Emile Pouget’s ‘Sabotage’’ by Louis C. Fraina from New Review. Vol. 2 No. 2. February, 1914.

Sabotage. By Emile Pouget. Translated from the French, with an Introduction by Arturo Giovannitti. Chicago: Chas. H. Kerr & Co.

This book is a description of Sabotage by a protagonist and man of action, who played an important part in its development in France. This indicates the chief defects of the book. It is a vivid confession of faith, vibrant with the spirit of the man of action immersed in the practical aspects of his subject, but uninterested or incapable of interest in its theory or systematic analysis. How does sabotage affect the revolutionary morale? What is its relation to the totality of the Movement and not alone to local struggles and immediate ends? On the larger and really vital aspects, Pouget is silent.

While the book is sober as a whole, it is not absolutely free of hysterical claims. Pouget indicates that sabotage is a weapon of emancipation. Giovannitti says: “Sabotage is the most formidable weapon of economic warfare, which will eventually open to the workers the great iron gate of capitalist exploitation and lead them out of the house of bondage.” They refute their own claims. Pouget excellently compares saboters to “guerrillas” in national wars. When were guerrillas the “most formidable weapon” in such wars? Was not a people dependent upon guerrillas alone ultimately conquered? Sabotage “consists only in slackening work or temporarily disabling the instruments of production.” Sabotage develops instinctively as a proletarian weapon of last resort. It is most necessary and effective, according to Pouget, when workers on strike are beaten back to work; and then sabotage, terrible and silent, may win where the strike lost. This places sabotage in its proper perspective, and simultaneously proves that it is not “the most formidable weapon of economic warfare.”

What Pouget proves, and proves convincingly, is that sabotage is a valuable auxiliary weapon of the revolutionary union. Pouget’s sabotage does not mean violence, actually excludes violence; yet other saboters, as the German Arnold Roller, consider any act of violence-sabotage, even the “blowing up” of the “social tyrant,” the capitalist. “The consumer must not suffer from sabotage,” says Pouget; yet there are saboters who stop at nothing. This confusion of ideas is responsible for much of the opposition to sabotage.

There is another defect in Pouget and Giovannitti, and nearly all saboters. They are cursed with the mania of their opponents, the mania of justification. Its opponents generally condemn sabotage as being “ethically unjustifiable”; while saboters retort vehemently by damning ethics or justifying sabotage as in harmony with “proletarian ethics.” Giovannitti’s brilliant introduction is largely an “ethical” defense of sabotage; while Pouget alternately sneers at and answers the “ethical” argument. The principle involved in sabotage, says Pouget, is that the end justifies the means. To prove that the end justifies the means, however, is not at all to “justify” sabotage or prove its validity as a proletarian weapon.

Rejecting the end-justifies-the-means theory means rejecting the facts of human experience. The individual and the mass have generally acted, consciously and unconsciously, in the spirit of the end justifying the means. It has been a vital impulse in all ages and all philosophy. Pragmatism, that eminently respectable philosophy, blesses it; for to hold that things must be tested by experience, that it matters not whether an idea or action is right or not so long as necessary and effective, is to hold that the end justifies the means. Particularly is this principle necessary in a revolutionary movement, since the ruling class uses all the mystifications of morality and justice to paralyze revolt.

The principle involved in sabotage, accordingly, is a vital one. But it is not necessarily a revolutionary principle. It is a method, a mode of action, determined by expediency. The capitalist, according to Pouget, practices sabotage; is the capitalist, then, revolutionary? The conservative craft unionist must be a revolutionist, since he is an instinctive adept in sabotage.

Sabotage needs a systematic analysis of its relation to American conditions. How much of the alleged success of sabotage in France is due to small-scale industry? To what extent is it applicable to the large, highly organized American industry, with its intricate methods of superintendence and its efficiency system? Giovannitti might profitably discuss these phases of sabotage, necessarily neglected by Pouget.

New Review was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. In the world of the Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Maurice Blumlein, Anton Pannekoek, Elsie Clews Parsons, and Isaac Hourwich as editors and contributors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 on, leading the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable archive of pre-war US Marxist and Socialist discussion.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1914/v2n02-feb-1914.pdf