This wonderful biographical sketch by the veteran German revolutionary Paul Frölich served as the introduction to a collection of Danton’s speeches for the ‘Voices of Revolt’ series.

‘George Jacques Danton’ by Paul Frölich from Voice of Revolt, No. 5. International Publishers, New York. 1928.

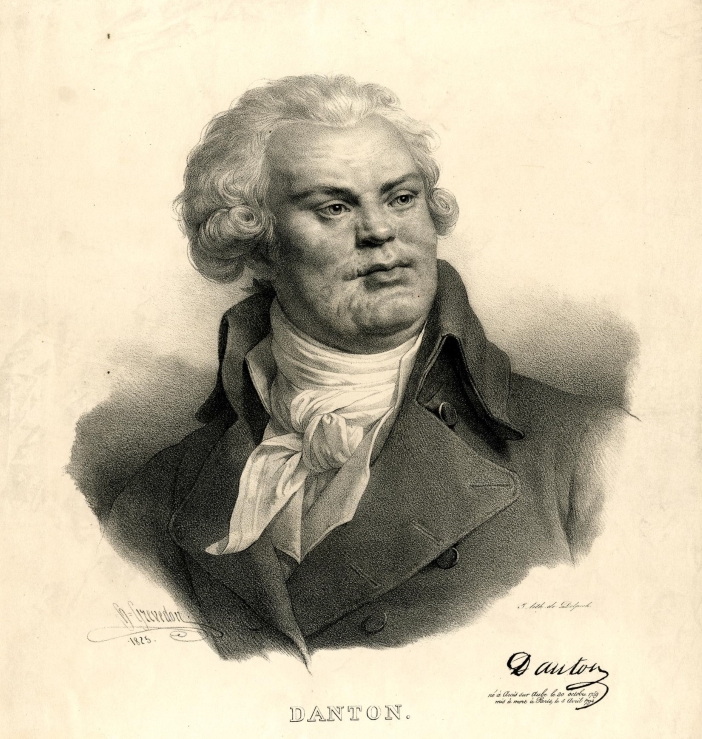

He was a man of Herculean proportions, with a massive head over a muscular neck, a broad brow, prominent broad nose, a sensuous mouth, and a vigorous chin. His fleshy face, disfigured by the smallpox, is expressive of a sense of humor, a delight in life, passion and will. Such is Danton. Such is Danton. Michelet says of him that his whole bearing was redolent of masculinity. “He had something of the lion, something of the bulldog, and much of the steer.” He is immoderate in enjoyment and wasteful of his powers. He lacks pertinacity, he lacks a patient, devoted application to the attainment of a single end. He is not a theorist. He is a man of action; in the moment of action, his energies riot to the full, like a torrent breaking down a mountain chain. At such moments, he lashes men on; he is himself a man of bold decisions and great measures. He is impeded by no petty considerations, by no fear. At bottom, he is of kindly nature, but when necessity demands it, he becomes ruthless to the point of brutality.

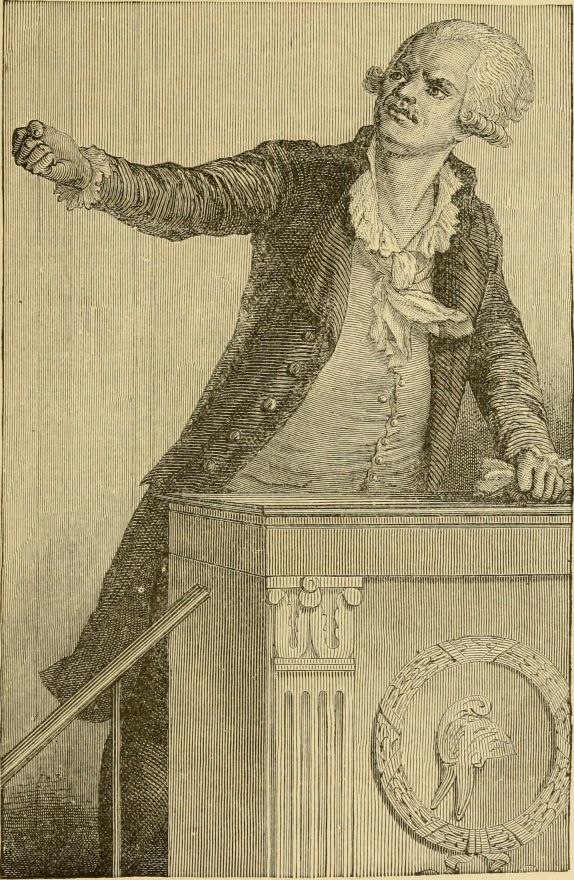

His voice is sonorous, his speech impetuous, his gestures impressive, dramatic. He seizes his hearers and drags them to him. His opponents have rebuked him for his coarse, cynical, and vulgar speech, which seemed to have been dragged through the filth of the gutter. They assert that he maneuvered for the applause of the multitude by means of low comparisons and coarse jokes, of which many an anecdote is retailed, but these all are in contradiction with the speeches that have been actually preserved. There are not many such speeches: a few delivered in the Club of the Jacobins, a speech delivered to the Paris Town Council, another to the National Assembly, and the speeches delivered in the Convention. Unlike the other orators of his time, he took no steps to preserve his fame. He never gave the journalists any manuscripts. Others might meticulously prepare their speeches, adorn them with fine phrases, and then read them in the Parliament or in the club. These were mere written speeches, academic disputations! Danton always spoke extemporaneously. His words poured forth without guidance.

Therefore his frequent repetitions, but therefore also his immense and direct influence. His speech rolled along in mighty billows, supported by his inner emotion. He was fond of many-colored plastic pictures. He often confused them, however, and then his opponents covered him with ridicule. They ridicule him also because he often speaks of himself, because he boasts with naïve pride of his athletic powers and lauds his present and future performances. But he does not speak in order to magnify himself. He is not one of the irresistibles. He speaks only when he has something to say. In almost every case, his speech ends with the proposal of some concrete measure, destined to save the situation. And in most cases his proposals result in resolutions by the Convention.

Danton’s name is associated with all the great events of the Revolution. Together with Marat, he is one of the orators and agitators in the Jardin du palais royal. He appears to have participated in the storming of the Bastille, for we find him two days later at the head of a detachment which arrests Soulès, the governor of Paris. He is one of the founders of the Club of the Cordeliers, which is recruited from among the radical elements of the district, the revolutionary intelligentsia, court officials, advocates, students, actors and petty bourgeois. He is soon made president of this club, which becomes an asylum for Marat and which for a long time constitutes, together with the theorizing Club of the Jacobins, the organization of the revolutionary initiative and finally becomes the fulcrum of the power of the Hébertists. When the arrogant nobility at Versailles demands the overthrow of the National Assembly and the putting down of the people of Paris, Danton succeeds in having the Cordeliers adopt a resolution which already contains in germ the thoughts of the decree “The nation is in danger!” namely, the active resistance to the royalist provocations and the arming of the revolutionary people. On October 4, 1789, this resolution is posted on the walls and has the effect of an appeal to insurrection. On the following day, the women of Paris, armed with pikes, muskets and cannons, proceed to Versailles in order to clean up the hotbed of counter-revolution. Danton is one of the first to sound the note of battle against the magistracy of Paris, which would crush the popular movement by declaring a condition of siege, in order to secure to the respectable citizens alone the fruits of the Revolution. When Marat is about to be arrested, on January 9, 1790, by a detachment, Danton rushes to the Cordeliers and proposes that they meet force with force: “If necessary, we shall sound the alarm and appeal to the Faubourg St. Antoine.” He succeeds in having a resolution adopted, appointing five Commissaires for the Defense of Liberty, with the right to frustrate the execution in the district of any command that encroaches on the liberty of the citizens. A warrant is at once issued for Danton’s arrest also.

On November 10, 1790, Danton is the spokesman of a delegation of the forty-eight Paris districts, which demands and attains the overthrow of the counter-revolutionary ministers by the National Assembly. He becomes the commander of the National Guard of his district and soon thereafter of the Department of Paris. On April 18, 1791, Louis XVI makes his first attempt to escape to St. Cloud. Danton, in a public appeal, preaches the necessity of armed insurrection and organizes the blocking of the roads by armed revolutionaries. After the flight of Louis XVI to Varennes, Danton fans the rising flame of revolution. While the parliament is making convulsive efforts to whitewash the king’s treason, the idea of the republic germinates in the masses. From the Club of the Cordeliers emanates the movement which leads to the great demonstration on the Champs de Mars, on July 17, 1791. On the Champs de Mars thousands signed the manifesto composed by Brissot and Danton, demanding that the perjured Bourbon be dethroned. The massacre on the Champs de Mars, caused by Bailly and Lafayette, the Friedrich Ebert and Gustav Noske of their day, crushes this movement. The parliament timidly capitulates before the bloody heroes of the day. A reign of terror begins; Marat, Robespierre and others are obliged to conceal them- selves; Danton for the moment returns to his native province. Hounded by spies, he goes to England for a few weeks. On September 12, he is again in Paris, and is joyously welcomed by the Club of the Jacobins. In December, he is elected alternate public prosecutor of Paris.

Now comes the turn of events which leads at a stormy pace to the culmination of the Revolution. The old powers, particularly Prussia and Austria, menace the Revolution. War is threatened; the royalists and the wealthy burgher section of the Revolution, the Girondists, help increase the danger of war. Some are already planning treason, praying for the defeat of France and the consequent restoration of absolutism. Others expect that the victorious war will lead to the consolidation of bourgeois rule by turning aside the passions of the masses from internal questions of class, to the matter of war. Marat and Robespierre, who see through these machinations, fight desperately against the advocates of war. They demand that the domestic enemy be put down, that the Revolution be consolidated. It will then be possible to defend the country and the Revolution, if necessary, to the utmost. After some vacillation, due to his fear of a split within the Jacobins, Danton also joins them. The war parties are victorious. In April, Louis XVI declares war on Austria, on the Austria with which he has already conspired.

The war leads the Revolution to the brink of destruction. Large portions of the army collapse at once. About a thousand officers, together with several complete regiments of foreign mercenaries, desert to the enemy. All confidence, all discipline, destroyed. The army is seized with a panic; defeat follows upon defeat; the domestic distress increases; the counter-revolutionaries are busily at work in their task of subversion. Louis XVI disorganizes the government; the parliament is cowardly and helpless. But the revolutionary energy is now crystallizing in the masses of the Paris population and in the departments. In Paris, the Cordeliers are at the head of the movement. On June 20, 1792, they come out in an armed demonstration, which ends, to be sure, with a farce in the palace, in which Louis XVI puts on a red cap and drinks blood-brotherhood with the people. But the demonstration reveals the power of the Paris sections.

The demonstration clearly shows that the Gordian knot cannot be untied but must be hewn apart. The parliament, hemmed in between revolution and counter-revolution, shrinks together to a mere nothing. Dangers increase apace. The Prussians cross the boundary with sixty thousand men; the Austrians invade Flanders with eighty thousand; Sardinian troops threaten the southwest; Spanish troops cross the Pyrénées. The Province of La Vendée rises to support throne and altar. The Duke of Brunswick issues a manifesto in which he threatens to rule with a conqueror’s rights and to raze Paris to the ground.

The Revolution appears to be lost. But the danger now increases the energies of the masses; the republican idea becomes stronger day by day; the citizens take arms into their hands. Their leaders still hesitate. Robespierre looks for a way to overcome the crisis by legal means. He finds a very imposing solution: dissolution of the parliament, convocation of a convention to be elected not only by the rich, active citizens, but by all the citizens, a convention which shall adopt a new constitution and control the executive authority. But the parliament is not capable of any revolutionary act. Legal methods will no longer suffice to solve the question.

The revolutionary action begins in the section of the Théâtre français (Cordeliers) of which Danton is president. On July 30, this section, in a solemn resolution, signed by Danton, Chaumette and Montmoro, abolishes the distinction between active and passive citizens and admits the propertyless to the communal assembly of the National Guard.

This is an open violation of the constitution, the proclamation of a new order, the creative initiative of the people. Most of the Paris sections follow this example. Danton obtains shelter in his district for the men from Marseilles, the “men who know how to die.” In the Hotel de Ville are assembled the voluntarily elected representatives of the sections, who force the old town council to the wall and constitute themselves as a revolutionary executive authority, parallel to the parliament. At the same time, the Central Committee of the Federated is constituted from among the representatives of the department, whose secret Directory prepares systematically for insurrection. Danton is the soul of the insurrection, the negotiator between the Commune and the Central Committee. For three weeks, Paris becomes an arsenal. After all the details have been prepared, the insurrection is set for August 10, 1792.

At sunrise, on this day, the sections line up in military array. The Commune assumes authority in a solemn proclamation. The commandant of the National Guard, Mandat, who plans to defend the palace of the Tuileries against the people with his troops, is arrested on Danton’s order, sentenced to death and disposed of. Louis seeks asylum with the parliament, which promises him the protection of the monarchy. Not long after, it capitulates to the Commune. Meanwhile, the Tuileries are taken by storm. The monarchy is dead. In the evening a new ministry is installed, consisting of Girondists and of the Tribune of the People of Paris, Danton.

Danton’s title is that of Minister of Distress. As a matter of actual fact, he is the inspirer and the wielder of the executive power. He whips up flagging energies, squeezes the utmost powers from the people and from the individual. He purifies the administration of justice and establishes elected judges. He organizes the battle against counter-revolution within the country and creates a revolutionary police. He imparts the first powerful im- pulse to the conscription of the masses for the creation of a revolutionary army, and soon brings about a condition in which two thousand men are daily supplied by Paris, ready to march.

Now come the bloody days of September. The Paris revolutionaries take the prisons by storm and sentence those that are suspected. They will not relinquish Paris to the royalists, they want their backs to be protected if they are to go to the front. It is stated that Danton watched these murders with his “hands in his pockets and his boots washed with blood.” This is not true. To be sure, he did not oppose this self-action of the masses, for he knew that terror was necessary in order to intimidate the enemies of the people, and because the revolutionary justice which was part of his program had not yet been created. Later, when the persecutions of the men of September began, Danton intervened in their favor with the words: “On August 10, the Revolution gave birth to republican liberty; on September 2, the afterbirth was disposed of.”

Meanwhile, the dangers are increasing. The Girondists in the government are cowards. They are afraid of the enemy and they are afraid of this Paris of the sans-culottes. They wish to transfer the government to the south, but Danton declares: “France is in Paris. To give up the capital means to hand France over to the enemy. In either victory or defeat, the defense of Paris will be between two fires, the republicans will be so weakened that the royalists will have a majority. In order to frustrate their plans, we must inspire the royalists with fear.” And he proceeded to act. On September 8, Danton is elected to the Convention. When faced with the necessity of choosing whether he would be a minister or a representative of the people, he resigned his ministerial portfolio, and insisted on this decision in spite of much beseeching from the Left. Yet he retained his influence, particularly on the war ministry and the diplomatic service. He pursued the goal as he did later in the Committee of Public Safety, securing a victorious termination of the war by means of weapons and by means of a destruction of the coalition of the powers through diplomatic agencies. As the Convention’s Commissaire for the Northern Army, he makes many journeys, he revolutionizes the masses of the people in Belgium, and brings about a union of Belgium and France. He reorganizes the Northern Army and corrects the political mistakes of the generals in the occupied regions. But he cannot prevent the treason of Dumouriez, whom he has trusted too much. This frightful blow against the re- public is simultaneously also a blow against Danton. The calumnies of the Girondists are now reinforced by the suspicions of the party of the Mountain. By his revolutionary activity, by the creation of the revolutionary tribunal, by his constant urging of action, he may indeed reduce this suspicion to silence, but he can no longer slay it. Furthermore, there is an additional element: his conciliatory role in the struggle between the Gironde and the Party of the Mountain, until he finds himself obliged to aid in the overthrow of the Girondists, after the latter have attempted to incite the provinces against Paris and have come out frankly for counter-revolution. In July, 1793, he resigns from the Committee of Public Safety and gradually relinquishes his position in the forefront of public events.

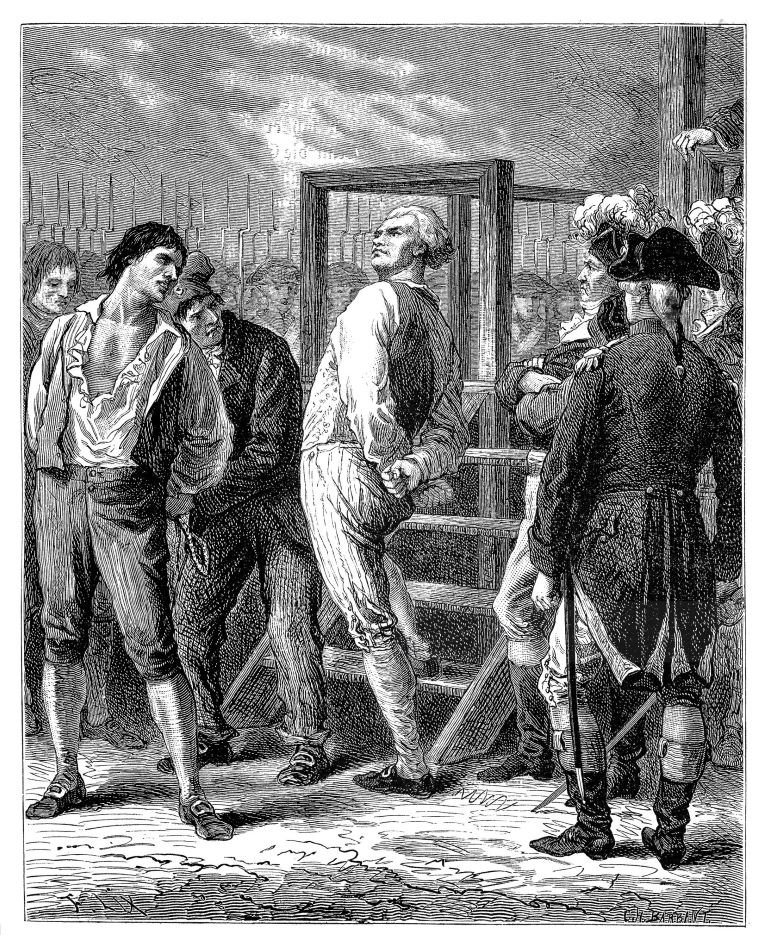

The great dangers are now passed. The armies of the Revolution advance victoriously. He plans a diminution of the sharpness of the Terror. He inspires the attacks by Desmoulins on the Hébertists, who have deprived him of his influence in the Club of the Cordeliers. He surrounds himself with associates who are worm-eaten with corruption. After the overthrow of the Girondists he gives Desmoulins free rein in his struggle against Robespierre and the Terror, which Robespierre himself desires to limit little by little. On 16 Germinal (April 5, 1794), at the age of 34, Danton mounted the scaffold, courageously, as he had lived. To the hangman he said: “You will show my head to the people; it is worthwhile!” Three months later, on 9 Thermidor, the great epoch of the Revolution closes with the fall of Robespierre.

The struggle between the parties in the great Revolution still rages to this day in the conflict of all historians.1 Some persons elevate Danton into a superman, others make him a common babbler, a purchasable creature, a traitor. None of these is right. Danton’s rise, as well as his tragic end, are indissolubly connected with the enhanced spirit of class struggle which constitutes revolution. Danton was a member of that stratum of independent intellectuals which furnishes leaders to the various parties in every revolution, particularly in the bourgeois revolution. These men occupy a socially intermediate position between the bourgeoisie and the petty bourgeoisie. If they take the side of the lower strata of the lower classes, they will be able to maintain themselves in the moment of actual struggle against the bourgeoisie, only by severing all the bonds connecting them with the bourgeoisie. Danton did not do this. Danton was the enemy of the counter-revolutionary classes and in his struggle against them he displayed all his active energy. He was the national revolutionary, and mobilized all the powers of the people, including the proletariat and the peasants, for the saving of the fatherland. He led the petty bourgeoisie and the proletarian strata of Paris to power. But when these classes defended their specific interests against the bourgeoisie, he failed to understand, and then–after Marat had destined him to be dictator–he lost his leadership. In this struggle he stands between the classes, and for this reason he makes repeated fruitless efforts to restore unity in the Club of the Jacobins, unity between the Gironde and the Mountain; and these efforts cost him the confidence of the masses of the Paris population. In the French Revolution, all the leaders fell, including those leaders who de- fended the interests of the petty bourgeois and proletarian strata against the bourgeoisie, either because they adopted half-way measures or set up demands for which the time was not yet ripe. This dilemma ultimately leads to the day of 9 Thermidor. Danton represents this class interest only to the extent that it does not seriously endanger the unity of front with the bourgeoisie in the period of revolutionary ascent. Much though he feels for the poor, he rarely has more than charity for the propertyless. This was the reason why his destruction-since he was ground between two opposing classes-was inevitable.

It was inevitable that he would become a victim of the struggle of factions. He was too great to stand between the classes. And he was too great, also, to withdraw from the fight. He tried to do so. He never overcame the effect of the overthrow of the Girondists, who had opposed him most viciously. Furthermore, there were other elements in his defeat. He was counting on the overthrow of the British dictator Pitt, on the victory of the Whigs, and therefore on peace with England. His whole diplomatic system was built up on this expectation. But in uniting Belgium with France and attacking the Netherlands, he made impossible any victory of the Whigs and any settlement with England. This experience discouraged him. He retired to private life; but he remained the man whose gestures were watched for by all, whose opinions were eagerly heard by all. When all the parties hostile to the republic had been destroyed, when he now organized the Right Wing, when he shrugged his shoulders at the decrease of social struggle (maximum prices, measures against speculation, etc., under pain of death), when he advocated moderation, and when his adherents even took up the struggle against the Committee of Public Safety-Danton, against his own desire, became the point of concentration of the entire counter-revolution, the hope of all those who had trembled before him. Robespierre and Saint-Just now had no choice; they had to destroy him in order to assure the rule of their class and of the Revolution. But, in devising for this purpose an indictment full of idiotic accusations, and in participating in the rending f its own flesh by the party of the Revolution, and thus weakening it, they became the victims of the same tragic destiny that had overtaken Danton.

Only the petty bourgeoisie could achieve the victory of the French Revolution, thereupon to relinquish its rule and the fruits of victory to the bourgeoisie. Having allied themselves completely with the petty bourgeoisie, Marat and Robespierre became the greatest political leaders of the Revolution. But Danton will retain the distinction conferred upon him by Karl Marx, the distinction of having been the greatest master of insurrectionary tactics in the bourgeois revolution.

1. The zeal of the parties in this conflict was often ridiculous. The Dantonist Robinet even counted Danton’s pocket handkerchiefs in order to clear his hero from the charge of corruption. The Robespierrist Mathiez accumulates a veritable mountain of data in order to justify every word in the accusation against Danton, which is a party document of the basest type.

Speeches of George Jacques Danton. Voices of Revolt No. 5. International Publishers, New York. 1928.

The fifth in the Voices of Revolt series begun by the Communist Party’s International Publishers under the direction of Alexander Trachtenberg in 1927.

Contents: Biographical Sketch and Introduction by Paul Frolich, The Overthrow of the Ministry (November 10, 1790), Accusing LaFayette (June 21, 1791), A Confession of Faith (January 20, 1792), The Struggle with the Domestic and Foreign Foe (August 28, 1792), On the Troubles at Orleans (September 22, 1792), On the Election of Judges (September 22, 1792), Make Way for the Poor (September, 1792), Unity and Strength (March 10, 1793), Creation of the Revolutionary Tribunal (March 10, 1793), How Can France be Saved? (March 27, 1793), On the Transformation of the Committee of Public Safety into a Provisional Government (August 1, 1793), On Free Public Instruction (August 13, 1793), The Formation of a Revolutionary Army (September 5, 1793), On the Use of Political Methods (September 6, 1793), Danton’s Defense Before the revolutionary Tribunal (April 2-5, 1794), Explanatory Notes. 97 pages.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of original book: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/voices-of-revolt/05-George-Jacques-Danton-VOR-ocr.pdf