On the night of December 4, 1859 German revolutionaries in Cincinnati, Ohio united with Black abolitionists over the martyrdom of John Brown and pledged themselves to the destruction of slavery.

The Birthplace of the U.S. Left by Revolution’s Newsstand.

German Radicals Across the River from Slavery

Cincinnati, Ohio was once a stronghold of radicalism, anarchism, and socialism. Thanks in large part to the influx of refugee German ’48ers, exiles from the failed democratic revolutions that broke out across Europe in the mid-19th century. Many, though not all, of came from the southern, largely Catholic, German-speaking lands.

A radical working-class German neighborhood, Over-the-Rhine, developed. The name originated as a derogatory joke by the city’s American-born, who christened the Miami Canal, a fetid, industrial sewer that separated the community from downtown, the “Rhine.” The name was soon adopted (appropriated?) by the German community itself.

It was a place of socialist and labor conferences, union organizing, Marxist and anarchist study circles, working-class libraries and sporting facilities, beer halls and high-profile visits of international revolutionaries like Wilhelm Liebknecht and Eleanor Marx.

Over-the-Rhine was the site of a rising in 1853 by those immigrants. Catholic though many were, they were also anti-clerical, and violently protested against the visit of an arch-reactionary Papal emissary Cardinal Bedini, associated with putting down the European democratic revolutions many had invested their hopes and lives in.

Women were predominant in the march to the city’s main Cathedral, carrying banners saying: “Down with Bedini!” “No Priests, No Kings!” “Down with the Butchers of Rome!” and “Down with the Papacy!” They were met with bullets and police charges with several deaths.

Reactionary Protestant nativists whipped up anti-German sentiment for bringing “the European disease of revolution” to the city in the aftermath. Also, Germans drank. Even on Sundays.

That sentiment exploded two years later as nativist “Know Nothing” bigots, led by the newly elected “American Party” mayor brought to power on the strength of an anti-immigrant vote, attacked those immigrant quarters in days of violence, including the use of cannon on both sides.

Utilizing their experiences from the European uprisings of 1848, and the strength of their neighborhood organization, militias were mobilized, barricades along Vine Street and other roads were erected and Over-the-Rhine was successfully defended. Know-Nothingism emerged badly damaged and would lose much of its power in the city. Dozens were killed.

Cincinnati had five radical “Turner Halls” and “Freeman” societies connected with the community, and a dozen newspapers. Unlike many Irish immigrants of the time, and despite the Republican’s association with the Know-Nothings, this community formed a mass base of white abolitionism in Cincinnati and a number of other Midwestern cities.

Cincinnati, Ohio. December 4, 1859. Birthplace of the U.S. Left

One of those German radicals, August Willich, Marx’s sometime foil in the Communist League and Engels’ military commander in the Baden revolt, immigrated to the city in the 1850s and quickly became a leader of the community. He edited a number of working-class papers and organized political societies from offices in 1419 Main Street, the building is still there.

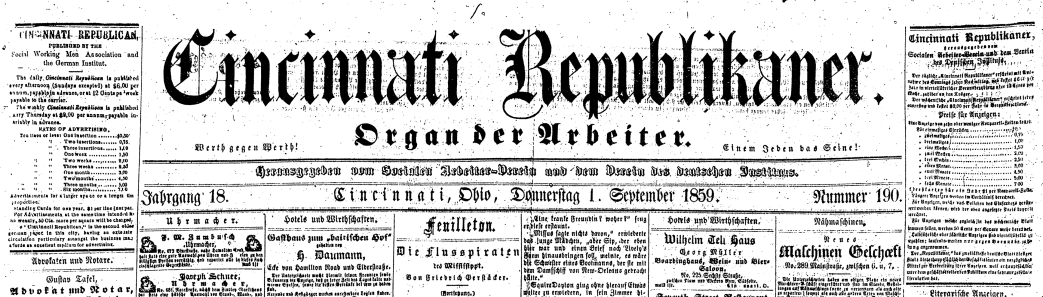

His ‘Cincinnati Republikaner’ paper was the first daily communist paper, marks the beginning of radical left publications in the U.S. as we would understand them. An organ of Cincinnati’s Social German Workingmen’s Association, Der Socialer Arbeiter-Verein, representing the city’s large German-speaking Red 48er immigrant population.

It would be edited by Marx’s one-time foe promoted his work, enthusiastically publishing Marx’s 1859 Kritik der politischen Oeconomie (Critique of Political Economy) just as it was released in Europe. This is the first publication of that work in the United States. The Republikaner gave voice to supporters of Garibaldi and the European Revolution, to local workers and Turner societies, to scientific and cultural debate, to the communist movement, as well as to the growing struggle against slavery. The Republikaner had connections to John Brown reported on his activities well before Harper’s Ferry in October of 1859

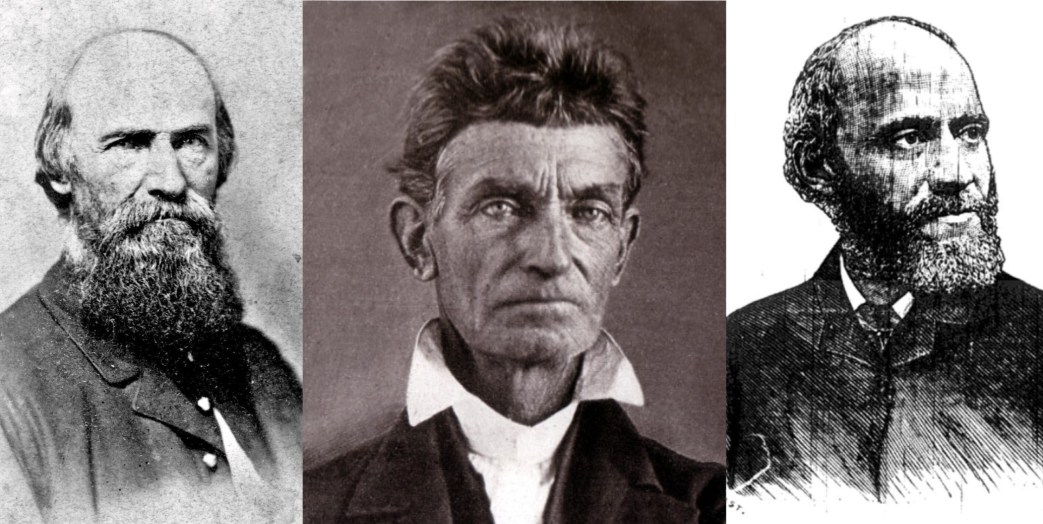

If there was a time and place we could say the modern U.S. left was born it might be at Cincinnati’s Arbeiter Hall the night pf December, 4 1859. There, Willich and Der Socialer Arbeiter-Verein joined forces with militant Black Cincinnati in mobilizing support for John Brown and his army in the aftermath of Harper’s Ferry, including a multi-racial rally complete with torches and red flags. German revolutionary immigrants uniting with Black radicals, Peter H. Clark who possibly the first Black socialist in the US was co-organizer, in a multilingual, multi-national, working class gathering over the very American struggle against slavery at the martyrdom of John Brown.

Welcoming the war and determined to make it one of abolition, radical German Cincinnati greeted Lincoln as he visited the city on his way to Washington with a uniformed military parade and this promised German workingmen’s arms to fight the slave-owners:

TO ABRAHAM LINCOLN, PRESIDENT ELECT OF THE UNITED STATES.

Sir, We, the German free workingmen of Cincinnati avail ourselves of this opportunity to assure you, our chosen chief magistrate, of our sincere and heartfelt regard. You earned our votes as the Champion of free labor and free homesteads. Our vanquished opponents have, in recent times, made frequent use of the terms, “workingmen” and “workingmen’s meeting,” in order to create an impression, as if the mass of workingmen were in favor of Compromises between the interests of free labor and slave labor, by which the victory just won would be turned into a defeat. This is a despicable device of dishonest men. We spurn such Compromises. We firmly adhere to the principles which directed our votes in your favor. We trust that you, the self-reliant because self-made man, will uphold the Constitution and the laws against secret treachery and avowed treason. If to this end you should be in need of men, the German free workingmen, with others, will rise as one man at your Call, ready to risk their lives in the effort to maintain the victory already won by freedom over Slavery.

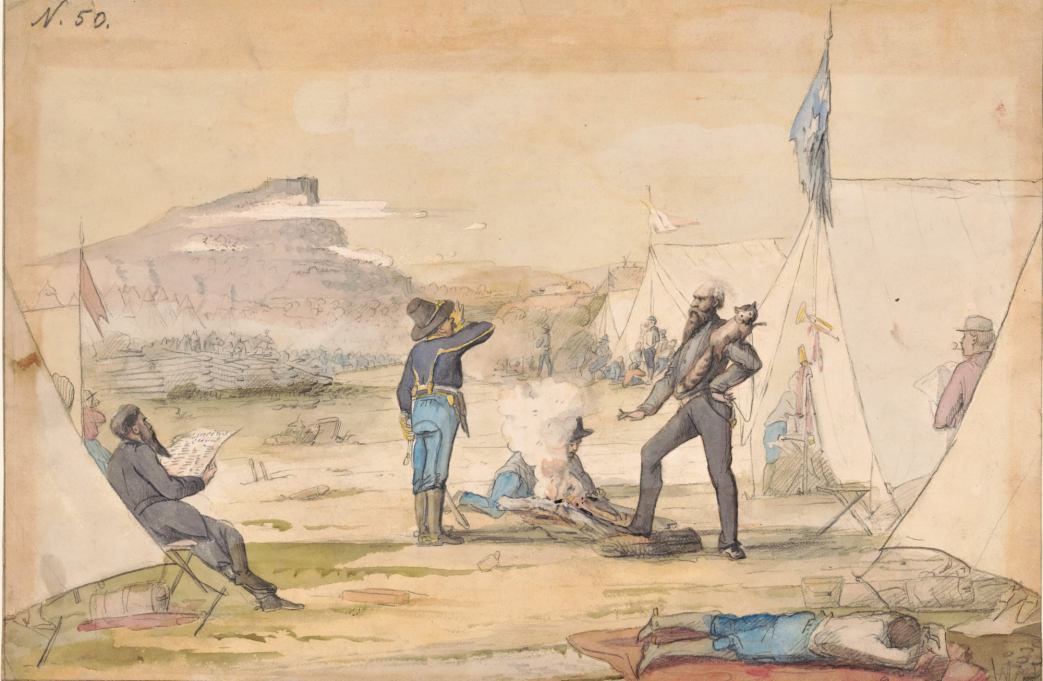

The Republikaner would later be instrumental in raising two of the most left-wing units in the Civil War, the German-speaking 32nd Indiana and the 9th Ohio. The militias, birthed in the violence of the previous decade, and organizations of Cincinnati’s German working class, became the backbone of the city’s Union enlistment early in the Civil War as Germans flocked to defend the republic. And for some, the chance to destroy slavery. August Willich was the chief summoner of these volunteer recruits and was just one of a number of exiles associated with Marx and the European revolutionary movement with leading roles in the American Civil War. He joined the 9th Ohio Infantry (“Die Neuner”) as a lieutenant and was soon given a command in the 32nd Indiana, another all-German unit, as a result of his success in recruiting to the new Union Army.

John Brown’s Body

From there he fought with great ingenuity and tenacity as he rose up the ranks from Colonel to Major General at the end of the war. He led his men at Shiloh, where he had the regimental band play the ‘La Marseillaise’ as they marched to the front.

Captured at Stone’s River, he was sent to the Confederate’s Libby Prison, a hell-hole of which he said, “We were insulted and reviled. The only ones who accepted us, cooked for us, or did us favors at every opportunity were the slaves…who viewed us as their liberators.”

Confined when the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, on his release in a prisoner exchange, he remarked to a Cincinnati gathering of 3000 greeting his return that the war was “no longer a battle about nationality, but one in the interest of all humanity.” He immediately reported back to duty.

After the extraordinary conduct of his men in the Chickamauga campaign he wrote of them, “again and again proven that they are true sons of the Republic, who value life only so long as it is the life of a freeman, so that they may make every power, slaveratic or monarchial bend before the commonwealth of the freeman…”

At the Siege of Chattanooga, he led his troops up the steep incline of the fog-shrouded Missionary Ridge, capturing it against all odds, breaking the siege and opening the way to Atlanta.

As commander of the 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, XIV Corps, Army of the Cumberland he joined Sherman’s Atlanta campaign, being badly wounded at the battle of Resaca in May, 1864, ending his combat career. Of the 905 original members of Willich’s 32nd Indiana, only 281 were left to muster out three years later.

Called “Papa” by his adoring men, he referred to them as “Citizen” outside of formal duty. As much as possible, he assigned like-minded fellow officers. He required ovens for fresh bread be built at every stop so his men would not have to eat hardtack rations, made sure they had beer, insisted that the regimental chaplain be a freethinker, and read aloud the proclamations of the First International to his troops. He distributed revolutionary papers and had the regiment create its own paper, led (lectured) the ranks of the 32nd in studying everything from astronomy to the Peasants Revolt of 1524.

Also, General Willich had a pet racoon as a constant companion, often perched on his shoulder. He was not boring.

After his injuries took him from the field, he was made Military Commander of Cincinnati for the remainder of the war. Quite a turnaround for the leader of a community that less than ten years earlier were victims of a mass pogrom in the city. An indicative example of the profound, even revolutionary, change ushered in during and after the Civil War.