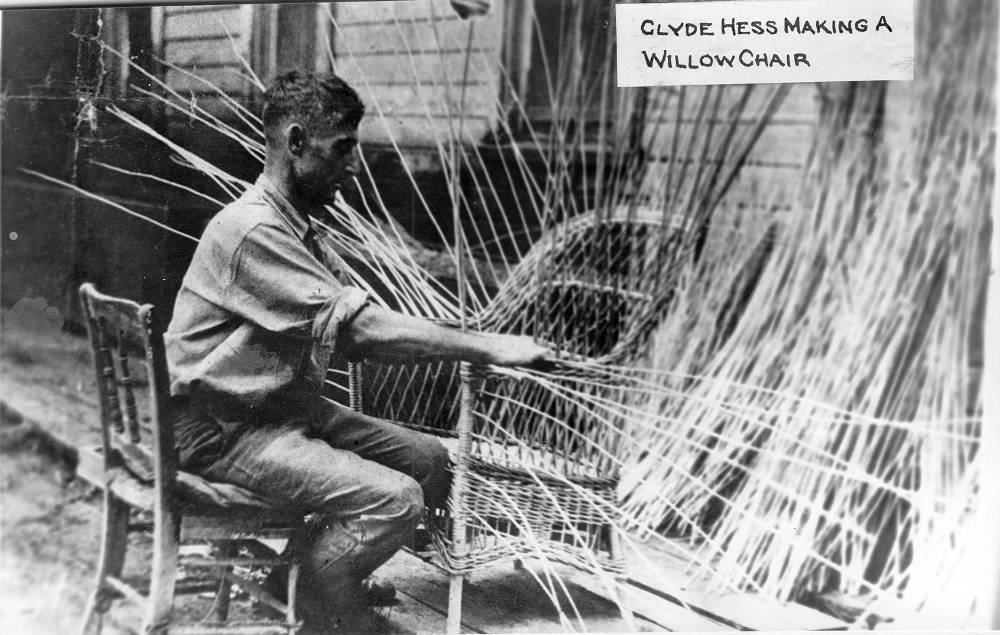

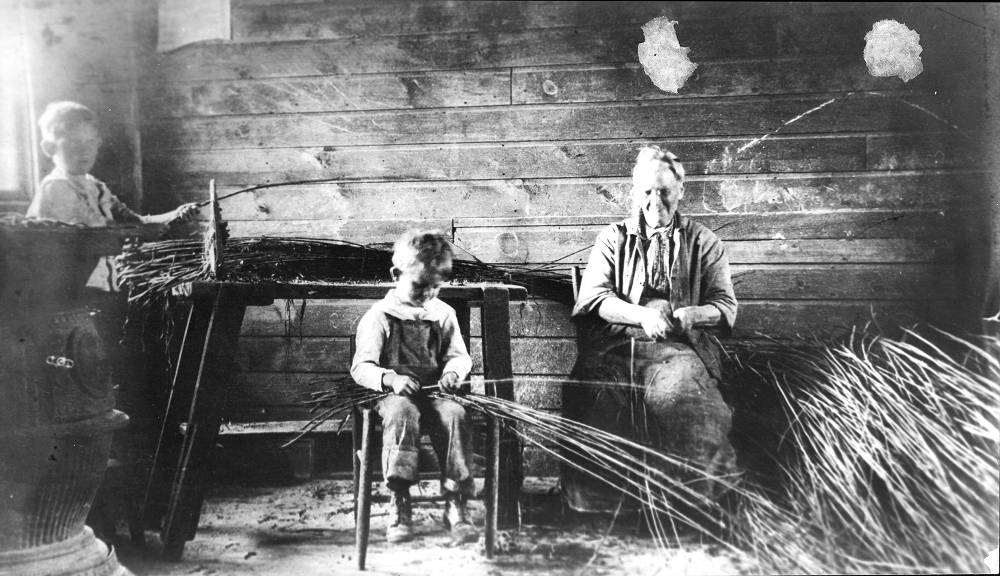

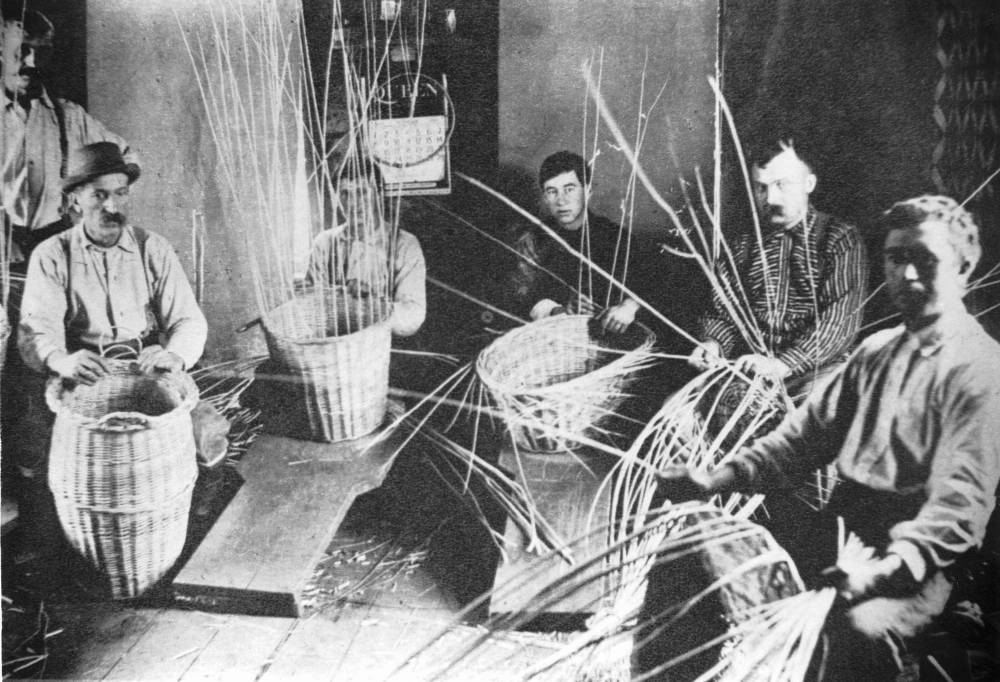

The village industry of Liverpool, New York; willow baskets and furniture made by the state’s prisoners and impoverished local families.

‘Willow Workers’ by J.J. Corcoran from The Weekly People. Vol. 13 No. 6. May 9, 1903.

Though Machinery Has Not Invaded Their Trade, Wages and Conditions Are Miserable.

Syracuse, N.Y. A new slave-pen of capitalism has just been brought to light. It is a village of twelve hundred souls situated on the bank of Onondaga Lake about eight miles from Syracuse. These twelve hundred–men, women, and children–are all engaged in the manufacture of willow baskets.

This community consists of members of various nationalities, chiefly Germans, whose ancestors, settled there about half a century ago when the salt industry flourished. But the salt industry finally died out, and the workers. turned their attention to basket making.

One of the peculiarities of the latter industry is that although it is utterly devoid of machinery from the cutting of the willow to the finishing of the basket, wages have gone down until they are now miserable–barely affording an existence. Though the machine has not superseded the man and the shears, it is not the capitalists’ fault. On a number of occasions they have experimented with different patents only to see them fail, as the willow being brittle has always been cracked by the strain of the machines. The cause of the decline of the willow workers’ wages has been brought about by the basket of that material being replaced by different articles made of metal, etc., which is produced by machinery and the willow ware must compete with.

Agents of the capitalists are dispatched to the districts where willows are grown to buy up the product two and three years before it is ready for the market.

After the willow is harvested it is turned over to the State penitentiary to be dried and stripped by the convicts. For this the capitalists pay seven dollars, where formerly they had to pay the natives of this locality nine and ten dollars.

From the convicts the willow is delivered to the wage-slaves of this community, who, the capitalists having purchased all the raw material, have to accept what their exploiters proffer. At present $1.75 per dozen is the wages. On inquiring how many clothes baskets a skilled workman could make in eight hours, I was informed on each occasion about five and a half to six baskets. One can readily see what these people have to live on. These slaves of capitalism commence their tasks at four and five o’clock in the morning and work until eight and nine o’clock at night. It was the interior of these people’s “homes” that first attracted my attention to their economic condition. On knocking at their “parlor” doors I was greeted on most occasions by women with care-worn faces, whose children were not “hanging to their mothers’ apron strings,” but were busy in the “dining rooms shaping the rods of willow upon which depends the food for their little mouths. In another “living” room sat the father working the rods into baskets.

Where there are four boys in the family, whose assistance can be applied to making baskets, the father receives a little better remuneration by buying enough stock in winter to keep them supplied for the rest of the year. But even he will have to sell his product to the capitalist from whom he bought the raw material or he will be refused stock the next time he applies for it. At present there is but one family thus situated. It makes about two dollars a dozen.

The exploiters of the working class have their agents among these willow workers, in the shape of clergymen, who instill on the workers’ minds “that their miserable condition is their lot in life; that there is no remedy for it whatever, but on the other side of this world–after life.” That is the answer one gets from them when speaking of their economic conditions.

The majority of these workers are Prohibitionists, politically. It suits the capitalists to have them such for if they do not use liquor they can work for so much less than those wage-slaves that do.

Section Onondaga County, Socialist Labor Party, will hold a few meetings in that locality and endeavor to teach these misled wage-slaves that there is a remedy for their lot in life right here on earth; that they need not wait till they get “on the other side of this world–after life” to get their reward. They will never get it till they become class-conscious by voting into power the party of their class–the Socialist Labor Party–and thus rear the Socialist Republic, under which their cook stoves will be removed to their proper quarters. When that is done they will be able to distinguish their workshop from their home.

New York Labor News Publishing belonged to the Socialist Labor Party and produced books, pamphlets and The People. The People was the official paper of the Socialist Labor Party of America (SLP), established in New York City in 1891 as a weekly. The New York SLP, and The People, were dominated Daniel DeLeon and his supporters, the dominant ideological leader of the SLP from the 1890s until the time of his death. The People became a daily in 1900. It’s first editor was the French socialist Lucien Sanial who was quickly replaced by DeLeon who held the position until his death in 1914. After De Leon’s death the editor of The People became Edmund Seidel, who favored unity with the Socialist Party. He was replaced in 1918 by Olive M. Johnson, who held the post until 1938.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-slp/030509-weeklypeople-v13n06.pdf