As bad as turpentine can be for workers using it in their labor, the production of it–done almost entirely by Black workers in the swamps of the Deep South–was a hellish and deadly undertaking. The radical Health magazine exposes the various stages of this industrial poison that murdered many and made the DuPonts rich.

‘Workers and the Turpentine Industry’ by E. Lippincott and Robert Lehr from Health. Vol. 1 No. 2. June, 1934.

ONE morning several years ago a healthy insurance underwriter came into his sunny office in downtown Atlanta. He sat at a polished desk and opened the mail. Out of a long brown envelope marked “confidential,” he yanked a little bulletin, and rapidly uncreased it. The insurance underwriter was a very busy man; he didn’t intend to spend more than a minute studying this confidential bulletin a report to insurance men and selected industrialists on the hazards of turpentine to workers in that industry, and in related industries.

The underwriter didn’t like to read unpleasant literature, so he squinted a little in pain as he read a list of some symptoms and the effects of turpentine poisoning on workers. He read that the men who put tin troughs and clay pots on the slashed trees in Southern pine forests, to catch the dripping pitch, are “prone to a low grade dermatitis.” That just means they were likely to get skin disease from their miserably paid work. Then he read that employees in turpentine distilleries and refineries were subject to acute dermatitis, severe irritation of bronchial tubes, throat and lungs, and severe renal (kidney) ailments.

The report on the hazards of turpentine then said something about the effect of the chemical on housepainters, enamellers, lithographers, textile workers and others.

As he sat there in his sunny office, this particular underwriter wasn’t much interested in what turpentine, or benzol either, did to the skin or lungs of painters, enamellers, lithographers and textile workers. He was somewhat interested, however, in the effect of the volatile liquid on men who worked in the pine forests of South Carolina, Georgia, Florida. As an insurance underwriter he had to know just what risks those workers ran of getting sick or dying from exposure to the raw fumes of turpentine. If they got sick too often, or if too many of them died in any industry, the insurance companies would have to hoist the rates in order to keep up profits on the policies. It was this desire to keep the rate of profit on industrial insurance policies at a high level, that caused some American insurance corporations some years ago to finance a laboratory out in Cincinnati. This laboratory is in charge of a skilled toxicologist, who has doctors, chemists and technicians at his command. The institution is called “The Industrial Health Conservancy Laboratories.” In its offices a file clerk can look up a typewritten report, or dig into a cabinet, and tell you what percent of the workers in the National White Lead Company plant suffered from lead poisoning last year. A good looking secretary saunters up to a desk humming a dance tune and lays down a memorandum full of figures on the number of cement plant workers that probably died of silicosis or tuberculosis in 1930.

Don’t get us wrong–this laboratory doesn’t put out its valuable information to workers. The reports are for insurance companies and industrialists. They are a great aid to an underwriter trying to calculate how high a premium he should charge on an industrial policy. This report an Atlanta agent was scanning stated:

“The manufacture of turpentine, because of racial restrictions in underwriting, provides a relatively small number of applicants to engage the attention of the underwriter.”

Plainer, more downright English would read:

“Negroes are the only people who work in the turpentine industry. We don’t insure negroes who work in this game.”

Why aren’t negroes eligible for insurance if they work in the pinewoods gathering pitch, or in distilleries or refineries? The answer is that the health hazards of such work are too great to make the workers good risks.

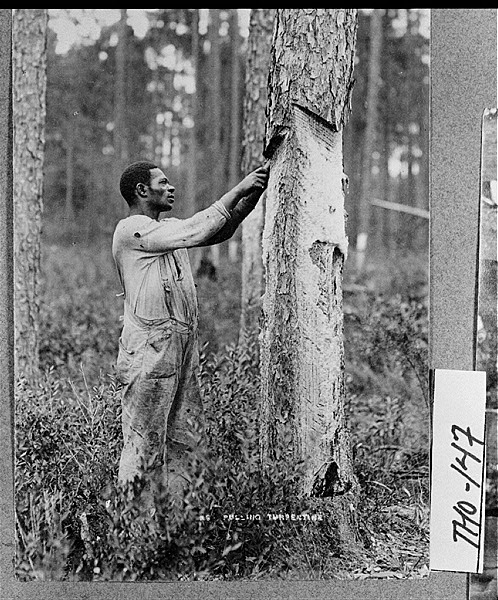

In the Southern pine forests about twenty-five thousand workers produce turpentine. They attach troughs and pots to trees, collect the pine pitch, haul it to small-scale distilleries parked in the middle of the deep woods, heat the pitch in a cauldron. The volatile fumes rise to the top of the kettle and escape through a coil, emerging as gumspirits of turpentine.

Of these twenty-five thousand workers in the turpentine industry in the South, 89 1/2 percent are Negroes. Any distillery foreman will tell the inquirer: “This isn’t any work for a white man.”

Skin disease, kidney trouble, bronchial coughs, are so common among these workers as a result of long exposure to the fumes, that they can’t get insurance at any price.

“Oke,” thought the underwriter as he finished reading the report. He chucked the bulletin into a tray with the thought, “Any fool knows we don’t insure negroes who work in the turps camps.”

But that’s only part of the story of the workers in the turpentine industry: a Florida automobile tire salesman told us:

“The turpentine business has been hit so hard in the depression that the men who own distilleries have had to make nearly all their profit out of their commissaries, their company stores. You see, those camps strung out all through the woods have about forty or fifty workers apiece. Around ten of them work in the distillery, and the rest gather the gum from the trees and bring it into camp. During the off-season the manager of the camp advances them credit for grub and clothes. They live in company shacks, get their rent free. They’re always in debt to the company, so they sort of have to trade at the store. Beside, they’re stuck way off in the woods, a hell of a way from any town. So the manager is able to make a little extra money on the side.”

An old story, and this time the scene is not a Pennsylvania or Kentucky mining town, but is in the deep pine woods of the far South.

In Jacksonville and Brunswick, Georgia, and other Southern cities, giant turpentine plants distil and refine the product by mass production methods. Some of the largest refineries are owned by the munition-making, millionaire Dupont family. In these plants the turpentine is not made by collecting drip gum and heating it until the vapors pass off and condense into a liquid. Instead, company tractors go into cut-over forest lands. The tractors drag pine stumps out of the soil. Trucks take the stumps to the large distillery, where huge machines shred and grind the wood. Turpentine is extracted from the pulp by a steam-distillation process.

This method of making turpentine has been gradually putting the small scale forest distilleries out of business. The small distillery can produce only turpentine and rosin. A Dupont factory can produce not only turpentine from pine stumps, but it also turns out formaldehyde, acetone, phenol, wood alcohol, acrolein (a war gas), formic acid and a half score of other chemicals. These by-products sometimes fetch the Dupont family more money than the turpentine itself.

For the negro and white workers in these giant plants, however, there is a catch to this efficient mass-production of turpentine: The dangers to health are much greater in working with stump, steam-distilled turpentine plants, than in the more primitive plants producing gumspirits. For example, gumspirits of turpentine (made from the pitch collected from trees) was used in a plant painting department that employed 50 workers. The department averaged 3 cases of turpentine poisoning each year. In the interest of economy, the manager began buying steam-distilled turpentine, made from stumps. At the end of 2 months 35 of the 50 workers in the department were suffering from turpentine poisoning.

In a large distillery, as the turpentine goes through process after process, the toxicity of the liquid becomes greater. In the plants, workers have violent headaches, they suffer spells of dizziness and weakness. The senses become dulled, sometimes hemorrhages occur from the kidneys. Workers must urinate frequently. Rasping coughs can be heard all through the factory.

Does a Dupont worry about the health of negro workers in his turpentine refinery or distillery? Take a guess. The report of a toxicologist says:

“Generally speaking, no particular provisions are made for the welfare of workers, although large plants have first-aid stations.” A factory worker with skin disease, a kidney ailment, or respiratory difficulty induced by turpentine must get great comfort out of knowing there’s a first-aid in the place, in case he falls and breaks an arm.

Can anything be done to guard the health of workers in the turpentine industry? Much. But that would mean in one way or another that the Dupont Company and its competitors, large and small, would see a slice taken out of their profits. Workers in the industry by mass protest against dangerous occupational hazards and miserable living conditions could better their health. But only in a Workers Land, where industry is managed by workers, and not by foreman paid by millionaire refinery-owners, would intensive and efficient study be given to health hazards in the turpentine industry-and the results of the research used to protect the health of the workers-and not the profits of insurance underwriters, bankers and manufacturers.

Turpentine is widely used in a variety of industries. In the words of a toxicologist:

“The product turpentine enters in numerous industries and its toxicity may be an important factor in some apparently unrelated processes.”

Correct. For example, nobody knows how many painters have fallen off high scaffolds and killed themselves on the sidewalk below because of sudden dizziness, weakness, and lack of muscular coordination caused by breathing in turpentine. New York City’s Commissioner of Health in 1918, Dr. Lewis Harris found after examining 402 house painters:

That 142, or 34% of the men had recently experienced severe intoxication from turpentine.

That 70% of the 402 painters had had one or more attacks of some sort of poisoning attributable to turpentine or related substances, such as acetone or benzol.

Dr. Harris described some of the symptoms he found in the workers: Difficulty in breathing, irritation of the eyes, sudden weakness of the legs, vomiting, and dizziness—“resulting often in falls from scaffolds.”

Recently an industrial health expert made a tour of 10 lithographing plants. In 4 out of the 10 plants he examined, there was serious danger of turpentine and benzol poisoning to workers in various departments.

The British Inspectorate of Factories has a compilation of dermatitis cases that have been voluntarily reported. (This means the list isn’t a complete one.) For the years 1924, 1925 and 1926, 7.2 percent of all skin disease cases reported were due to exposure of workers to turpentine or turpentine substitutes. For the next 3 years about 8.1 percent of skin disease cases were reported as being due to this cause.

The British ruling class permits its government to keep at least a feeble, incomplete record of some of the major industrial hazards to health. In the United States the industrialists who hire workers and recklessly expose them to the fumes of toxic chemicals, without a thought as to means of abolishing dangers to the workers’ health, do not even permit their false-face government to keep any records. They do not permit their government to make even a slight pretense at safeguarding the health and lives of workers who toil in turpentine camps or distilleries, or pain America’s skyscrapers and houses, or print calico or lithograph posters or spray metal furniture with enamel.

Because the profits of the turpentine industry must be raised enough to bring a smile to the Dupont face, must workers have kidney ailments, must they wear skins covered with spreading sores, and cough from raw throats and lungs?

The answer must come from the workers themselves!

Health was the precursor to Health and Hygiene and the creation of Dr. Paul Luttinger. Only three issues were published before Health and Hygiene was published monthly under the direction of the Communist Party USA’s ‘Daily Worker Medical Advisory Board Panel’ in New York City between 1934 and 1939. An invaluable resource for those interested in the history history of medicine, occupational health and safety, advertising, socialized health, etc.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/health-luttinger/v1n2-jun-1934-Health.pdf