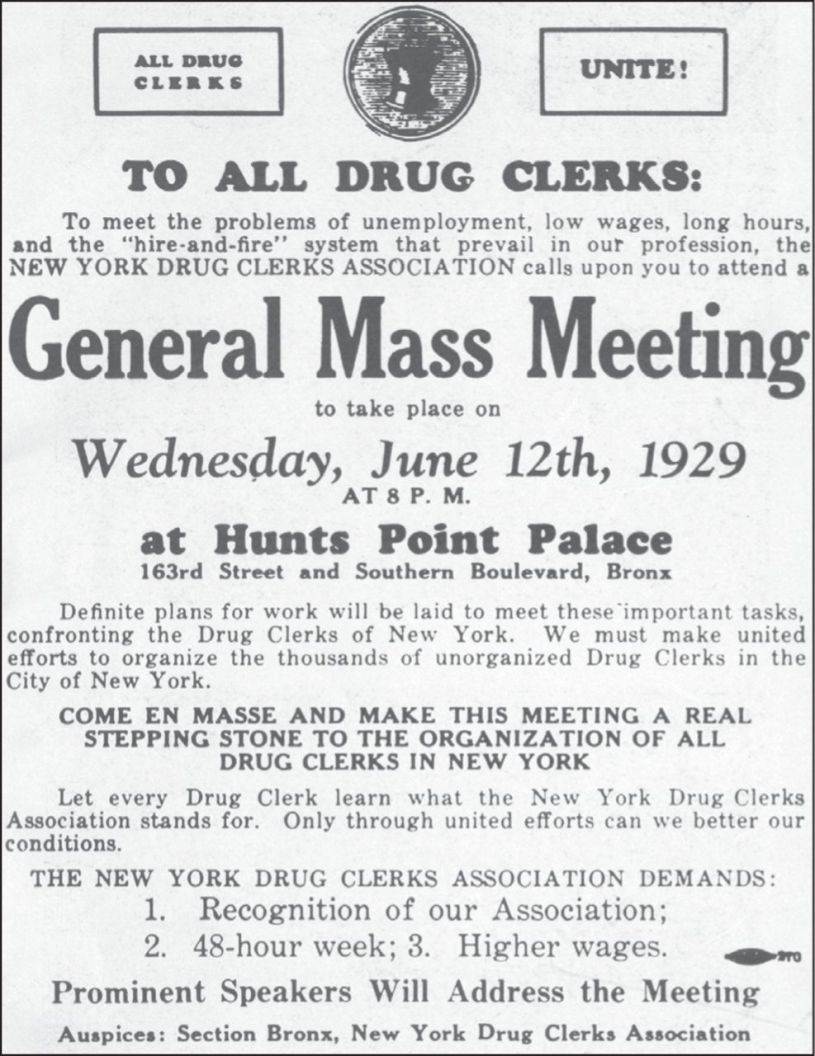

While many of the industries presented on this site have contracted or died in the United States, not so the pharmaceutical industry and the drug store. Taking a minor 1931 strike at Halper’s Pharmacy in New York, Dreyer’s article looks at the subjective condition of workers and how not to organize a union, and will be recognizable to all labor activists of today.

‘The Drug Clerks and the Class Struggle’ by I. Dreyer from The Militant. Vol. 5 Nos. 25 & 26. June 18 & 25, 1931.

The Drug Clerks’ Union local 581 of the A. F. of L., is conducting a “strike” at Halper’s Pharmacy, 180th Street and St. Nicholas Ave. Halpers’ refused to sign a collective agreement with the union. The store employs two licensed pharmacists, one union pharmacist, two soda-fountain clerks and a porter.

This new experience has already become a decisive factor in the further development of the Drug Clerks’ Union and a source from which important conclusions of organizational strategy should be drawn.

Picketing is undoubtedly a highly effective weapon in the hands of the workers, if efficiently wielded, to extract concessions from the bosses. But it is no less effective as a means to arouse the dormant class instinct of the worker and put him on the road toward class consciousness. There, on the picket line, he clearly sees the living alignment of the police and judiciary forces and the entire governmental machine with his boss against him and his fellow workers, drawing the class lines of the contending forces in the most contrasting colors. However, these class lines of the struggle are usually blurred under the reactionary leadership of the reformist and reactionary union. The case of the drug clerks, as the writer of these lines has had the opportunity to observe, the enlightening effect of picketing is quite glaringly manifest.

It is highly interesting and instructive to observe a drug clerk put on the strike-placard for the first time. He dons it timidly, reluctantly, casting shy glances at the passers-by. For even those drug clerks who have joined the union are still imbued with the asphyxiating idea of “professionalism”, which blurs their real position on the social scale of our class society. But after a few hours of picketing a noticeable change in his gait and facial expression takes place. The meek-gloomy look disappears and a ray of proud resoluteness lights up his countenance. He notices with fervent admiration that the working class element responds favorably to the pickets and that it manifests a gratifying solidarity. “And why shouldn’t they? We are also workers”, he remarks proudly. A few hours of picketing, an infinitesimally short period in a person’s lifetime, but what a thoroughgoing change may occur in one’s own outlook in so short an interval. I believe that the writer of these lines has not exaggerated when he remarked: “If it were only possible to have every member of the union to do a few hours of picketing, we would have a strong militant union.” Unfortunately, only a few of the members are doing picket duty. The greatest majority of the membership, however, have not only failed to participate in the activities of this so-called so-called strike, but have generally shown an attitude of indifference and distrust toward the union and its leadership. The reasons for such a state of apathy among the members are to be traced directly to the ideological makeup of the executive board and the manner in which it has been conducting the affairs of the union, which I shall discuss in the latter part of this article.

This so-called strike has made quite a commotion in the “higher spheres” of pharmacy. “A labor union has no place in as honorable” a profession as pharmacy. The strike method is particularly “degrading pharmacy to the low level of wage labor,” shriek the self-appointed peers of the various drug store owners’ associations and some backward clerks, who find consolation for their bitter lot in their false pride of being a “professional” man.

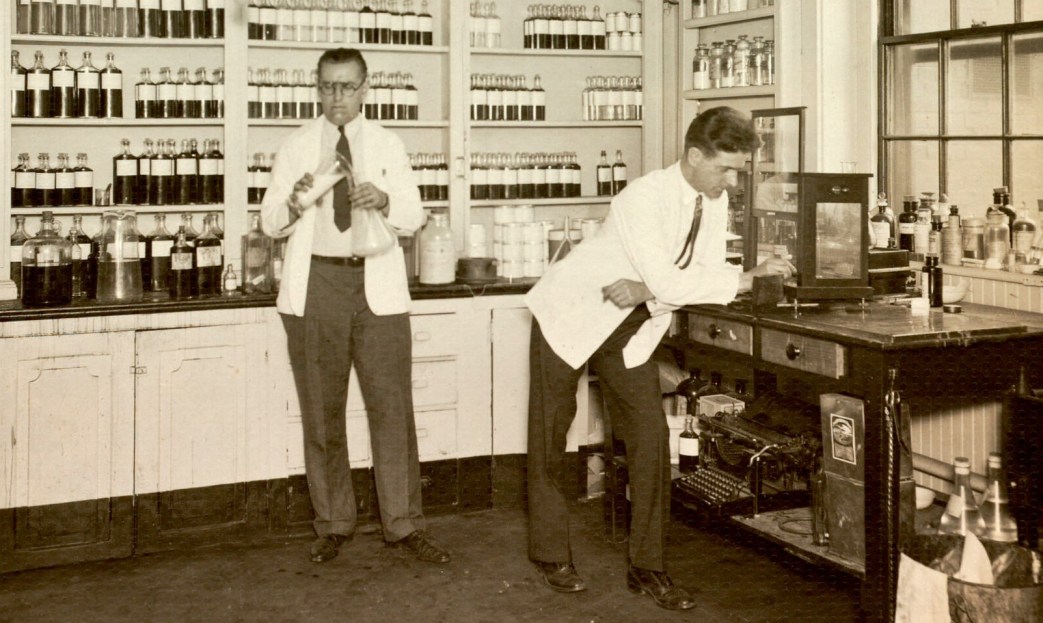

Yes, gentlemen of the “honorable profession” of pharmacy, “the bourgeoisie has, (long ago) stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honored and looked up to with reverent awe. It has converted the physician the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science into its paid wage-laborers.” (Communist Manifesto). Yes, bootleggers of the “honorable profession” of pharmacy, you have not only “lowered” it to the level of wage labor, but you have degraded it to an occupation of the underworld. You “ethical” pharmacists, who are so greatly concerned about the high standards of your “profession”, will not hesitate, for the sake of saving a measly penny to deprive the patient of the benefits of a medicine by substituting inferior, therapeutically void drugs, by dispensing moldy, deteriorated fluid extracts, tinctures, syrups and other medicinal preparations. For a measly weekly wage of twenty or twenty-five dollars you exploit your licensed or junior clerk seventy to eighty hours a week. And to qualify for such a lucrative position one has to be, besides, a licensed pharmacist, an expert soda dispenser and sandwich maker; he also is required to wash floors, run errands and other such “trifles”. No–it is not the standard of pharmacy that concerns you so greatly–but it is the resultant of the unionization of the drug clerks that you fear so much.

The New York Pharmaceutical Conference is acting as the spearhead in the present crusade against the union movement. It pours out torrents of demagogy and lies against it. Moreover, it has been attempting to behead it by organizing an auxiliary association of drug clerks under the guardianship of the Conference, i.e., a company union in its crystalline form. A serious challenge to the union movement among the drug clerks, however, cannot come from such an anemic organization as the New York Pharmaceutical Conference. Its whole existence has been an expression of impotence of the disorganized and prostrate drug industry. The real danger, however, is lurking from within the boundaries of the present “leadership” of the Drug Clerk’s Union.

The executive board of the Drug Clerk’s Union is composed of politically backward and organizationally inexperienced elements, incapable of giving independent leadership. The membership, naturally, is composed of the same backward elements; their ideology due to the professional veil and business basis of their occupation, is thoroughly petty bourgeois. Their attitude toward the union is extremely vague and indecisive. It is true that the earnestness of certain leading members of the executive board in the activities of the union is rather questionable. However, these elements, precisely because of the vacillating attitude of the membership toward unionism in general, the backwardness and ignorance of the executive in particular, have not so far been able to exercise any influence upon the membership. Consequently, the conditions for the growth of a militant opposition within the present loose frame-work of the union are highly favorable.

II.

It is obvious, that the principal task of the leadership of the Drug Clerks Union consists primarily in dispelling the illusion of professionalism, which is so greatly hampering the development and orientation of the drug clerk toward unionism, and raise him to the level of a class conscious worker. But, to perform this colossal task, the present leadership is particularly incapable.

The executive board, in order to cover up the tremendous gap between its position as a leader and its inability to lead, garbs itself in a cloak of secrecy. When a rank and filer asked the secretary, at the last membership meeting, to state the reasons for not reading the minutes of the executive meetings, she answered that, “certain methods of organization were discussed, which cannot be divulged at present.” Of course an organization at times must recognize the right of a leading body to deal with matters confidentially. At present, the truth is, the same manner as a cover serves an empty container in a window-display: to convey an impression of genuine merchandise. The minds of the executive members are not only bare of any “secret methods” but are perfect vacuums, as far as methods of building a union are concerned. “When a secret is kept too long it becomes no secret”, say the old folks. The executive has been secretive too long and has, naturally, aroused the suspicion of the membership as to the real motive behind the secrecy. Disillusionment followed; and their confidence in the leadership has been badly shaken. Hence the present state of apathy among the members.

The elementary method to disperse the suffocating illusion of professionalism among the drug clerks consists, quite obviously, in holding membership and educational meetings as often as possible, in order to present an opportunity to an and ever greater number of members non-members to express their views on matters pertaining to the existence and growth of the union. And in this manner attract their interest, arouse their enthusiasm, and direct this nascent enthusiasm into chambers of organizational activities, which will serve as motive power for the further progress and growth of the organization. The executive, however, has done the exact reverse. It has called meetings in an arbitrary manner; it is only at the last membership meeting that a motion was passed to hold membership meetings regularly, once a month. Until then, meetings were held whenever the executive needed the official sanction of the membership on some matter. For instance, the last membership meeting was called to ratify a certain “collective agreement”, about which I shall write at another opportunity.

It must be quite obvious that the first stage of organizational activities of the union, i.e., the transition from its amorphous state into an organized, unified and compact body, is far from being completed. As a matter of fact, it has not yet begun. To skip this stage and pass over to its second stage, i.e., to establish the union as a bona fide workers body and demand recognition from their bosses, is an adventurous move that is sure to meet disaster on its way.

The present so-called strike is an attempt by the executive board to skip the first stage of organizational activities and plunge into the second stage which may prove fatal to the feeble structure of the union.

The ushering in of the second stage of organized activities of a developing union on a yet unorganized industrial field is usually signalized by the clarion call of a general strike. However, a general strike of drug clerks, in times of an ever sharpening crisis and under conditions of a declining drug industry, presupposes not only the rallying of a decisive majority of licensed and junior clerks under the banner of the union but also the unqualified, organized support of the soda-fountain and luncheonette workers, who operate an important branch of the drug store business today. It goes without saying, that a capable revolutionary leadership is an unconditional prerequisite for its possible success.

A well organized minority of drug clerks, however, can and should develop a real struggle AGAINST WAGE CUTS AND LONG HOURS in one or two stores. Such a struggle will necessarily draw the membership into the activities of the strike: picketing, distributing circulars, organizing open-air meetings, etc., which will teach them a valuable lesson in the class struggle and free their minds from the fetters of professionalism–the greatest obstacle on their road toward consciousness.

Moreover, such a strike will touch a sore spot in the hearts of the unorganized clerks, arouse their sympathy and cause them to gravitate toward unionism. In this manner, the union will augment its forces and give greater assurance to the success of the strike and its spreading to other establishments. Even in case of failure, which might result from the crushing pressure of the brutal law of the club and the injunction, it will disillusion them only with the “democracies” of capitalism rather than with the feasibility of organized resistance. It will only give rise to new methods of struggle. However, to attempt to “throw a picket at the door”, in order to compel the bosses to recognize the union and the clerks, “to join it up”, is a method of organization entirely inimical to working class organization strategy. This ‘make ’em join” strategy was originated and has been used by the A.F. of L. bureaucracy; it is the incarnation of its utter contempt for the working masses, and its manner of subordinating the membership to its despotic rule by alienating them from the activities of the union and cowing them into submissiveness.

In a period of industrial rebirth, the conditions for a “successful” application of this reactionary, purely A.F. of L. “make ’em join” strategy are often favorable. The history of many a local of the A.F. of L. has been written under its pressure. But in a period of an ever deepening crisis, the margin for its success is rather a precarious one.

However, the eminent failure of this “make ’em join” method of organization, as it is being applied by the budding bureaucracy of the Drug Clerks’ Union, is not only due to the crisis and the ever increasing unemployment but largely to the anti-working class contents of the strategy itself. For it is utterly devoid of any elements of appeal, which may arouse the personal interest and class solidarity of the drug clerks and thus result in their ever expanding union.

On the contrary, this “make ’em join” strategy is apt to precipitate confusion within the ranks, arouse the antagonism of the unorganized and in this manner result in an ever narrowing union of the drug clerks.

“What can we gain by this struggle? At the utmost a few new members of a rather doubtful quality and the unionization of a store where union conditions will never be enforced,” says one clerk to another disenchantedly.

“You cannot force me into the union–there are no jobs anyway,” cries defiantly the unorganized clerk.

Yes, fellow drug clerks! The success of such an attempt can only gain prestige for the bureaucracy and temporarily strengthen its position–but not one minim of benefit for you! Its failure, however, might cause the disintegration of the union movement among the drug clerks and set it back for a long period to come.

The executive board of the Drug Clerks’ Union, as I have already pointed out, is incapable of giving independent leadership and is, therefore, obliged to take advice and direction from “foreign” sources. Its most brilliant ideas usually emanate from Louis Sherman, head of the HOUSE OF SHERMAN that practically controls the activities of the union.

The members of this notorious house are as follows: (a) Louis Sherman, organizer of the Drug Clerks’ Union. This individual has never had any connections with the drug industry and has never organized any kind of a union. He succeeded, however, in impressing a group of drug clerks as being an “old hand” in organizing unions; his services were accepted and paid for. Now, since the union has become a local of the A.F. of L. outfit, he “severed” his relations with the union and became organizer of the so-called “Federation of Retail Druggists”, using the union as a tool to further his own interests.

(b) Mrs. Frances Gargle, Sherman’s sister, is secretary-treasurer of the union. Mrs. Gargle is a pharmacist has long ago abandoned the profession of pharmacy in favor of matrimony. Her awakened interest in pharmacy in general and in the union in particular is rather questionable.

(c) Mr. George Sherman, brother of Mr. Louis Sherman, is a leading member of the Executive Board and parades under the name of Gerson. He is not a Pharmacist, but a petty swindler, pure and simple. These facts MUST AND WILL BE EXPOSED before the membership at the coming meeting, which will undoubtedly lead to the downfall of the Sherman dynasty. However, the consequences of the upheaval cannot yet be foreseen.

The Militant was a weekly newspaper begun by supporters of the International Left Opposition recently expelled from the Communist Party in 1928 and published in New York City. Led by James P Cannon, Max Schacthman, Martin Abern, and others, the new organization called itself the Communist League of America (Opposition) and saw itself as an outside faction of both the Communist Party and the Comintern. After 1933, the group dropped ‘Opposition’ and advocated a new party and International. When the CLA fused with AJ Muste’s American Workers Party in late 1934, the paper became the New Militant as the organ of the newly formed Workers Party of the United States.

PDF of issue 1: https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/themilitant/1932/jun-18-1932.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/themilitant/1932/jun-25-1932.pdf